ARAVAIPA CREEK – BLACK FARM RIPARIAN REPORT by Mark D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sonora Sucker

scientific name common name Catostomus insignis Sonora sucker Bison code 010520 ______________________________________________________________ Official status Endemism ________________________ State AZ: threatened Colorado River Basin _______________________ Status/threats Dams, diversions, groundwater pumping and introduced species Distribution The species is widespread and abundant in the Gila and Bill Williams river drainages in Arizona and the Gila and San Francisco drainages in southwestern New Mexico. The species is widespread and abundant in the Verde and Gila headwaters. Habitat Streams and rivers from 300 to 3000 m in elevation, primarily in pool habitats. Pool habitats over sand gravel substrates. Life history and ecology Can attain a size of 0.8 m and a weight of greater than 2.0 kg. Used as food by early, primitive human populations. Food habits vary with availability. In one stream, Aravaipa Creek, it is principally a carnivore, whereas elsewhere in pool habitats diet consists of plant debris, mud, and algae. Observed to "suck" cottonwood seeds at surface as is common for the common carp. Young often feed in large schools at stream margins on micro-crustaceans, protozoans and other animal and plant groups. Breeding Similar to most slim-bodied suckers, the species spawns in smaller streams over gravel substrates. Males darken in color and often display extreme tuberculation. Males &(usually 2) flank a single, larger female. Gametes are emitted with considerable to extreme substrate agitation and fall into gravel interstices. Cleaning of gravels occurs much as reported for salmonid species. Key Habitat Components: pools with sand-gravel substrates for adults and shallow, low velocity riffles and backwaters for young Breeding season Protracted, from as early as January to February at low elevations to as late as July. -

Laughing Waters" 40

Press, W. H., B. P. Flannery, S. A. Teukolsky, and W. T. Vetterling. 1986. Numerical recipes: C 1990 by S.E.L & Associates The art of scientific computing. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press. Stalnaker, C. B. 1978. The IFG incremental methodology for physical instream habitat eval- uation. Washington, DC: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS / OBS-78 /81). Stier, D. J., and J. H. Crance. 1985. Habitat suitability index models and instream flow suitability curves: American shad. Washington, DC: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS/ OBS-82 /10). The Recreational Impact of Trihey, E. W. 1979. The IFG incremental methodology. Pages 24-44 in G. L. Smith, editor. Proceedings of the workshop in instream flow habitat criteria and modeling. Information Series Reducing the "Laughing Waters" 40. Fort Collins: Colorado State University, Colorado Water Resources Research Institute. Valdez, R. A., and B. C. Nilson. 1982. Radiotelemetry as a means of assessing movement and of Aravaipa Creek, Arizona habitat selection of humpback chub. Pages 29-39 in W. Geer, editor. Transactions of the Bonneville Chapter of the American Fisheries Society. Salt Lake City, UT: Bonneville Chapter of the American Fisheries Society. Steven D. Moore Valdez, R. A., P. B. Holden, T. B. Hardy, and R. J. Ryel. 1987. Habitat suitability index curves Mary E. Wilkosz* for endangered fishes of the Upper Colorado River Basin. Final report to US. Fish and Wildlife Service (Contract No. 14-16-0006-86-055), Denver, CO. Stanley K. Brickler Received: May 3, 1989 School of Renewable Natural Resources Accepted: June 25, 1989 University of Arizona Discussion open until August 1, 1990 Tucson, Arizona 85721 ABSTRACT: The paper describes analyses that were conducted to de- termine the importance of water as an attribute of the recreational setting at Aravaipa Canyon Wilderness, Arizona, and the influence that reduced flows in Aravaipa Creek would have on visitors' perceptions of water quantity and quality. -

Aravaipa Canyon Ecosystem Management Plan

BLM Aravaipa Ecosystem Management Plan Final Aravaipa and Environmental Assessment Ecosystem Management Plan and Environmental Assessment Arizona • Gila District • Safford Field Office Field • Safford •District Gila Arizona September 2015 i April 2015 Mission Statements Bureau of Land Management The Bureau of Land Management (BLM) is responsible for managing the National System of Public Lands and its resources in a combination of ways, which best serves the needs of the American people. The BLM balances recreational, commercial, scientific and cultural interests and it strives for long-term protection of renewable and nonrenewable resources, including range, timber, minerals, recreation, watershed, fish and wildlife, wilderness and natural, scenic, scientific and cultural values. It is the mission of the BLM to sustain the health, diversity and productivity of the public lands for the use and enjoyment of present and future generations. Arizona Game and Fish Department The mission of the Arizona Game and Fish Department is to conserve Arizona’s diverse wildlife resources and manage for safe, compatible outdoor recreation opportunities for current and future generations. The Nature Conservancy The mission of The Nature Conservancy is to preserve the plants, animals and natural communities that represent the diversity of life on Earth by protecting the lands and waters they need to survive. Cover photo: Aravaipa Creek. Photo © Greg Gamble/TNC BLM/AZ/PL-08/006 ii United States Department of the Interior BUREAU OF LAND MANAGEMENT Safford Field Office 711 South 14th Avenue, Suite A Safford, Arizona 8 5546~3335 www.blm.gov/azl September 15, 2015 In Reply Refer To: 8372 (0010) Dear Reader: The document accompanying this letter contains the Final Aravaipa Ecosystem Management Plan, Environmental Assessment, Finding ofNo Significant Impact, and Decision Record. -

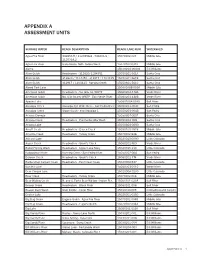

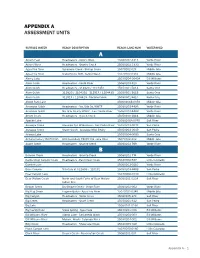

Appendix a Assessment Units

APPENDIX A ASSESSMENT UNITS SURFACE WATER REACH DESCRIPTION REACH/LAKE NUM WATERSHED Agua Fria River 341853.9 / 1120358.6 - 341804.8 / 15070102-023 Middle Gila 1120319.2 Agua Fria River State Route 169 - Yarber Wash 15070102-031B Middle Gila Alamo 15030204-0040A Bill Williams Alum Gulch Headwaters - 312820/1104351 15050301-561A Santa Cruz Alum Gulch 312820 / 1104351 - 312917 / 1104425 15050301-561B Santa Cruz Alum Gulch 312917 / 1104425 - Sonoita Creek 15050301-561C Santa Cruz Alvord Park Lake 15060106B-0050 Middle Gila American Gulch Headwaters - No. Gila Co. WWTP 15060203-448A Verde River American Gulch No. Gila County WWTP - East Verde River 15060203-448B Verde River Apache Lake 15060106A-0070 Salt River Aravaipa Creek Aravaipa Cyn Wilderness - San Pedro River 15050203-004C San Pedro Aravaipa Creek Stowe Gulch - end Aravaipa C 15050203-004B San Pedro Arivaca Cienega 15050304-0001 Santa Cruz Arivaca Creek Headwaters - Puertocito/Alta Wash 15050304-008 Santa Cruz Arivaca Lake 15050304-0080 Santa Cruz Arnett Creek Headwaters - Queen Creek 15050100-1818 Middle Gila Arrastra Creek Headwaters - Turkey Creek 15070102-848 Middle Gila Ashurst Lake 15020015-0090 Little Colorado Aspen Creek Headwaters - Granite Creek 15060202-769 Verde River Babbit Spring Wash Headwaters - Upper Lake Mary 15020015-210 Little Colorado Babocomari River Banning Creek - San Pedro River 15050202-004 San Pedro Bannon Creek Headwaters - Granite Creek 15060202-774 Verde River Barbershop Canyon Creek Headwaters - East Clear Creek 15020008-537 Little Colorado Bartlett Lake 15060203-0110 Verde River Bear Canyon Lake 15020008-0130 Little Colorado Bear Creek Headwaters - Turkey Creek 15070102-046 Middle Gila Bear Wallow Creek N. and S. Forks Bear Wallow - Indian Res. -

DEPARTMENT of the INTERIOR Fish

DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Fish and Wildlife Service 50 CFR Part 17 [Docket No. FWS-R2-ES-2010-0072] [MO 92210-0-0009-B4] RIN 1018-AX17 Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants; Endangered Status and Designation of Critical Habitat for Spikedace and Loach Minnow AGENCY: Fish and Wildlife Service, Interior. ACTION: Proposed rule. SUMMARY: We, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (Service), propose to change the status of spikedace (Meda fulgida) and loach minnow (Tiaroga cobitis) from threatened to endangered under the Endangered Species Act of 1973, as amended, and to designate critical habitat for both species. In total, we are proposing approximately 1,168 1 kilometers (726 mi) of streams as critical habitat for spikedace, and 1,141 kilometers (709 miles) of streams as critical habitat for loach minnow. The proposed critical habitat is located in Apache, Cochise, Gila, Graham, Greenlee, Navajo, Pima, Pinal, and Yavapai Counties, Arizona, and Catron, Grant, and Hidalgo Counties in New Mexico. DATES: We will consider comments received or postmarked on or before [INSERT DATE 60 DAYS AFTER DATE OF PUBLICATION IN THE FEDERAL REGISTER]. We must receive requests for public hearings, in writing, at the address shown in the FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT section by [INSERT DATE 45 DAYS AFTER DATE OF PUBLICATION IN THE FEDERAL REGISTER]. ADDRESSES: You may submit comments by one of the following methods: • Federal eRulemaking Portal: http://www.regulations.gov. Follow the instructions for submitting comments to Docket No. FWS-R2-ES-2010-0072. • U.S. mail or hand-delivery: Public Comments Processing, Attn: [Docket Number FWS-R2-ES-2010-0072]; Division of Policy and Directives Management; U.S. -

Mapping of Holocene River Alluvium Along the San Pedro River, Aravaipa Creek, and Babocomari River, Southeastern Arizona

Mapping of Holocene River Alluvium along the San Pedro River, Aravaipa Creek, and Babocomari River, Southeastern Arizona by Joseph P. Cook, Ann Youberg, Philip A. Pearthree, Jill A. Onken, Bryan J. MacFarlane, David E. Haddad, Erica R. Bigio, Andrew L. Kowler A Report to the Adjudication and Technical Support Section Statewide Planning Division Arizona Department of Water Resources Report accompanies Arizona Geological Survey Digital Map DM-RM-1 Map Scale 1:24,000 (6 sheets), 76 p. Originally issued, July 2009 Version 1.1 released, October 2009 Arizona Geological Survey 416 W Congress St., #100, Tucson, AZ 85701 Table of Contents Introduction 3 • Geologic Mapping Methods 3 • Mapping Criteria 3 • Ages of Deposits 5 Mapping the extent of Holocene alluvium 7 • Field data collection and access 8 • Surficial geologic contacts 8 • Soil Survey mapping 8 • Extent of Holocene River Floodplain Alluvium 16 • Geologic Map versions 17 Soil parameters and age estimates for soils in the southern San Pedro Valley 18 San Pedro River Geology and Geomorphology 22 • Geologic History 22 • Historical Change 23 • Geomorphology 24 • Modern channel conditions 24 Babocomari River Geology and Geomorphology 26 • Geologic History 26 • Historical Change 27 • Geomorphology 27 • Modern channel conditions 28 Aravaipa Creek Geology and Geomorphology 30 • Geologic History 30 1 • Historical Change 30 • Geomorphology 32 • Modern channel conditions 33 Geoarchaeological Evaluation 34 • Methods 34 • Results 35 List of map units 42 • Surficial units 42 • Other units 42 • Holocene river alluvium 42 • Pleistocene river alluvium 44 • Piedmont alluvium and surficial deposits 45 • Tertiary basin fill alluvium 51 • Bedrock units 54 References 71 2 Introduction The purpose of these investigations is to document and map the extent of Holocene channel and floodplain alluvium associated with the San Pedro River and its major tributaries in southeastern Arizona. -

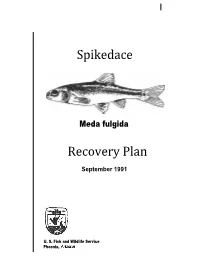

Spikedace Recovery Plan

Spikedace Meda fulgida Recovery Plan September 1991 U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service Phoenix, Arizona SPEKEDACE, Meda fulgida RECOVERY PLAN Prepared by Paul C. Marsh Arizona State University Tempe, Arizona for Region 2 U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Albuquerque, New Mexico Approved: Regiona D , U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Date: OP/ Spikedace, Meda fuldida Frontispiece i DISCLAIMER Recovery plans delineate reasonable actions which are believed to be required to recover and/or protect the species. Plana are prepared by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, sometimes with the assistance of recovery teams, contractors, State agencies, and others. Objectives will be attained and any necessary funds made available subject to budgetary and other constraints affecting the parties involved, as well as the need to address other priorities. Recovery plans do not necessarily represent the views nor the official positions or approval of any individuals or agencies involved in the plan formulation, other than the U.S. Fish Wildlife Service. They represent the official position of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service only after they have been signed by the Regional Director or Director as approved. Approved recovery plans are subject to modification as dictated by new findings, changes in species status, and the completion of recovery tasks. Literature citations should read as follows: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1990. Spikedace Recovery Plan. Albuquerque, New Mexico. 38 pp. Additional copies may be purchased from: Fish and Wildlife Reference Service 5430 Grosvenor Lane, Suite 110 Bethesda, Maryland 20814 301/429-6403 or 1-800/582-3421 The fee for the plan varies depending on the number of pages in the plan. -

Fishes and Aquatic Habitats of the Upper San Pedro River System, Arizona and Sonora

FISHES AND AQUATIC HABITATS OF THE UPPER SAN PEDRO RIVER SYSTEM, ARIZONA AND SONORA by W. L. Minckley, Ph.D. Professor of Zoology, Arizona State University, Tempe, Arizona 85287 Final Report for Purchase Order YA-558-CT7-001 U. S. Bureau of Land Management, Denver Federal Center, Building 50, P.O. Box 25047, Denver, Colorado 80225 March 1987 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ...... 1 Objectives 1 ...................................... DESCRI ON OF THE STUDY AREA 3 ...................................... HISTORIC AQUATIC CONDITIONS 6 .......................................... Man in the Upper San Pedro Valle:- 7 Aquatic Habitats of th,-, Past 10 ......................................... Permanence 13 ..................................... FISHES OF THE SAN PEDRO BASIN 14 ......................................... History of Study 14 Patterns of Ichthyofaunal Chanqe 16 Past Habitats and Fish Communities 19 Habitat Size ..... 20 Measures of Stability 22 Heterogeneity ..... 22 Species' Ecologies Relevant to Available Habitats ..... 23 Category I ..... 23 Category II ..... 27 Category III ..... 29 Category IV ..... 33 FACTORS AFFECTING LIFE HISTORIES OF NATIVE FISHES ... 37 ACTUAL AND POTENTIAL IMPACTS OF UPSTREAM M -:1.3 OPERATIONS 41 ENHANCEMENT OF SAN PEDRO RIVER FISH HABITATS ... 46 Semi-natural Habitats 47 Rehabilitation of the Natural Channel ...51 REINTRODUCTIONS AND MANAGEMENT OF NATIVE FISHES ...53 Philosophies,, 'roblems, and Realism= 53 Recommendations for Reintroduction and Management ...57 BIBLIOGRAPHY 62 INTRODUCTION Acquisition of much of the upper San Pedro River in the United States by the Bureau of Land Management (USBLM; Rosenkrance 1986) and its proposed designation as a "San Pedro Riparian National Conservation Area" (hereafter Conservation Area; USBLM 1986) presents a possibility for protection and management of a Southwestern stream and its plant and animal resources. Part of those resources are fishes, which due to their absolute dependence on surface water are sorely endangered. -

Appendix III

Appendix III Moments for each flood producing mechanism Annual Maximum Series Flood Frequency Moments for Tropical Cyclone Annual Maximum Series. N is the number of years with data on record. Flood Frequency Moments for Convective Annual Maximum Series. N is the number of years with data on record. Flood Frequency Moments for Synoptic Annual Maximum Series. N is the number of years with data on record. Flood Frequency Curves: Bulletin 17B Maximum ONLY 09379200 Chinle Creek near Mexican Water 09382000 Paria River near Lees Ferry 09384000 Little Colorado River above Lyman Lake near St. John’s 09393500 Silver Creek near Snowflake 09402000 Little Colorado River near Cameron 09424450 Big Sandy River near Wikieup 09424900 Santa Maria River near Bagdad 09426000 Bill Williams River below Alamo Dam 09432000 Gila River below Blue Creek, NM 09447000 Eagle Creek near Pumping Plant near Morenci 09448500 Gila River at Head of Safford Valley near Solomon 09468500 San Carlos River near Peridot 09471000 San Pedro River near Charleston 09473000 Aravaipa Creek near Mammoth 09480000 Santa Cruz River near Lochiel 09480500 Santa Cruz River near Nogales 09482500 Santa Cruz River near Tucson 09490500 Black River near Fort Apache 09492400 East Fork White River near Fort Apache 09497980 Cherry Creek near Globe 09499000 Tonto Creek above Gun Creek near Roosevelt 09504000 Verde River near Clarkdale 09504500 Oak Creek near Cornville 09505800 West Clear Creek near Camp Verde 09508500 Verde River below Tangle Creek above Horseshoe Dam 09510200 Sycamore Creek near Ft -

Appendix a Assessment Units

APPENDIX A ASSESSMENT UNITS SURFACE WATER REACH DESCRIPTION REACH/LAKE NUM WATERSHED A Ackers East Headwaters - Ackers West 15060202-3313 Verde River Ackers West Headwaters - Granite Creek 15060202-3333 Verde River Agua Fria River Sycamore Creek - Bishop Creek 15070102-023 Middle Gila Agua Fria River State Route 169 - Yarber Wash 15070102-031B Middle Gila Alamo Lake 15030204-0040A Bill Williams Alder Creek Headwaters - Verde River 15060203-910 Verde River Alum Gulch Headwaters - 312820 / 1104351 15050301-561A Santa Cruz Alum Gulch 312820 / 1104351 - 312917 / 1104425 15050301-561B Santa Cruz Alum Gulch 312917 / 1104425 - Sonoita Creek 15050301-561C Santa Cruz Alvord Park Lake 15060106B-0050 Middle Gila American Gulch Headwaters - No. Gila Co. WWTP 15060203-448A Verde River American Gulch No. Gila County WWTP - East Verde River 15060203-448B Verde River Arnett Creek Headwaters - Queen Creek 15050100-1818 Middle Gila Apache Lake 15060106A-0070 Salt River Aravaipa Creek Aravaipa Cyn Wilderness - San Pedro River 15050203-004C San Pedro Aravaipa Creek Stowe Gulch - Aravaipa Wild. Bndry 15050203-004B San Pedro Arivaca Lake 15050304-0080 Santa Cruz Arizona Canal (15070102) HUC boundary 15070102 - Gila River 15070102-202 Middle Gila Aspen Creek Headwaters - Granite Creek 15060202-769 Verde River B Bannon Creek Headwaters - Granite Creek 15060202-774 Verde River Barbershop Canyon Creek Headwaters - East Clear Creek 15020008-537 Little Colorado Bartlett Lake 15060203-0110 Verde River Bass Canyon Tributary at 322606 / 110131 15050203-899B San Pedro -

Aravaipa Creek Extant and Extirpated Native Fishes of Aravaipa Creek

REMNANT NATIVE FISH COMMUNITIES IN THE GILA RIVER BASIN RETAINING FIVE OR MORE NATIVE SPECIES Aravaipa Creek (not including species extirpated and then reintroduced) NO. OF NATIVE APPROX. LENGTH OF NO. OF NATIVE FISHES COMMONLY WATER OCCUPIED STREAM FISH SPECIES FOUND DURING BY NATIVE FISHES REMAINING ROUTINE SAMPLING 1 ASSEMBLAGE (miles) Gila River, upper (NM) (inc. East and West Forks) 8 8 120 Eagle Creek 8 6 40 Aravaipa Creek 7 7 20 Fossil Creek 6 5 15 White River (inc. East & North Forks) 6 4* 40 Verde River, upper (above Verde Valley) 6 3 40 San Francisco & Tularosa Rivers 5 5 125 Blue River (inc. Campbell & Dry Blue) 5 5 60 Black River (upper) (inc. East Fork) 5 5 35 Bonita Creek 5 5 35 Hot Springs and Bass Canyons 5 5 15 Redfield Canyon 5 4 15 Sonoita Creek (below Patagonia Dam) 5 4 10 Verde River, Verde Valley to Horseshoe Reservoir 5 4 80 Cherry Creek 5 4 40 Canyon Creek 5 4* 45 Tonto and Rye Creeks 5 3 45 1 Some species may be found only in local areas within the total reach, but are common in those locations. * Recent sampling records are unavailable outside of the White Mountain Apache Tribe. Extant and Extirpated Native Fishes of Aravaipa Creek (Stefferud and Reinthal 2004) EXTANT NATIVE FISHES EXTIRPATED NATIVE FISHES OF ARAVAIPA CREEK OF ARAVAIPA CREEK COMMON SCIENTIFIC FEDERAL COMMON SCIENTIFIC FEDERAL FAMILY FAMILY NAME NAME STATUS* NAME NAME STATUS* Cyprinidae longfin dace Agosia chrysogaster 2 Cyprinidae Colorado Ptychocheilus E squawfish lucius Cyprinidae speckled dace Rhinichthys 2 Catostomidae razorback sucker Xyrauchen -

Organochlorine and Trace Element Concentrations in the San Pedro

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Region 2 Contaminants Program bY Kirke A. King, Denise L. Baker and William G. Kepner’ U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Fish and Wildlife Enhancement Phoenix Field Office 3616 W. Thomas Rd., Suite 6 Phoenix, Arizona 85019 June 1992 ABSTRACT--The San Pedro River in southeastern Arizona sustains one of the richest, most diverse riparian areas in the United States. The San Pedro Riparian National Conservation Area is located near the headwaters of the river just north of the Arizona-Mexico border and includes nearly 112 kilometers (km) of prime habitat that is currently being considered for reintroduction of several endangered and threatened fish and mammal species. Organochlorine compounds apparently do not pose a threat to resident fish and wildlife. Survival and reproduction of endangered species relocated to this area would not be affected by current organochlorine levels. However, because of questionable analytical results, the data regarding trace elements are unclear. After this study was initiated, Apache Powder Company, located adjacent to the study area, was added to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s superfund list of hazardous waste sites. Additional contaminant problems possibly associated with Apache Powder Company such as ammonia, nitrate and trace element input into the San Pedro River should be assessed. We recommend that, 1) the San Pedro be re-sampled for nutrients and trace elements at the earliest possible date, 2) a cooperative interagency group initiate a regular chemical residue monitoring and bioassessment program, and 3) any reintroduction program be approached with caution given the areas history of recurrent mine spills and other potential contamination problems.