Elak, Liwa.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vinylnews 03-04-2020 Bis 05-06-2020.Xlsx

Artist Title Units Media Genre Release ABOMINATION FINAL WAR -COLOURED- 1 LP STM 17.04.2020 ABRAMIS BRAMA SMAKAR SONDAG -REISSUE- 2 LP HR. 29.05.2020 ABSYNTHE MINDED RIDDLE OF THE.. -LP+CD- 2 LP POP 08.05.2020 ABWARTS COMPUTERSTAAT / AMOK KOMA 1 LP PUN 15.05.2020 ABYSMAL DAWN PHYLOGENESIS -COLOURED- 1 LP STM 17.04.2020 ABYSMAL DAWN PHYLOGENESIS -GATEFOLD- 1 LP STM 17.04.2020 AC/DC WE SALUTE YOU -COLOURED- 1 LP ROC 10.04.2020 ACACIA STRAIN IT COMES IN.. -GATEFOLD- 1 LP HC. 10.04.2020 ACARASH DESCEND TO PURITY 1 LP HM. 29.05.2020 ACCEPT STALINGRAD-DELUXE/LTD/HQ- 2 LP HM. 29.05.2020 ACDA & DE MUNNIK GROETEN UIT.. -COLOURED- 1 LP POP 05.06.2020 ACHERONTAS PSYCHICDEATH - SHATTERING 2 LP BLM 01.05.2020 ACHERONTAS PSYCHICDEATH.. -COLOURED- 2 LP BLM 01.05.2020 ACHT EIMER HUHNERHERZEN ALBUM 1 LP PUN 27.04.2020 ACID BABY JESUS 7-SELECTED OUTTAKES -EP- 1 12in GAR 15.05.2020 ACID MOTHERS TEMPLE REVERSE OF.. -LTD- 1 LP ROC 24.04.2020 ACID MOTHERS TEMPLE & THE CHOSEN STAR CHILD`S.. 1 LP ROC 24.04.2020 ACID TONGUE BULLIES 1 LP GAR 08.05.2020 ACXDC SATAN IS KING 1 LP PUN 15.05.2020 ADDY ECLIPSE -DOWNLOAD- 1 LP ROC 01.05.2020 ADULT PERCEPTION IS/AS/OF.. 1 LP ELE 10.04.2020 ADULT PERCEPTION.. -COLOURED- 1 LP ELE 10.04.2020 AESMAH WALKING OFF THE HORIZON 2 LP ROC 24.04.2020 AGATHOCLES & WEEDEOUS HOL SELF.. -COLOURED- 1 LP M_A 22.05.2020 AGENT ORANGE LIVING IN DARKNESS -RSD- 1 LP PUN 18.04.2020 AGENTS OF TIME MUSIC MADE PARADISE 1 12in ELE 10.04.2020 AIRBORNE TOXIC EVENT HOLLYWOOD PARK -HQ- 2 LP ROC 08.05.2020 AIRSTREAM FUTURES LE FEU ET LE SABLE 1 LP ROC 24.04.2020 ALBINI, STEVE & ALISON CH MUSIC FROM THE FILM. -

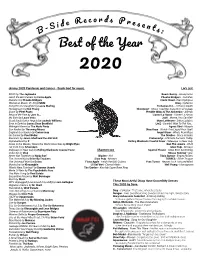

Best of the Year 2020

r d e R e c o s P r e s S i d e n t B - s : Best of the Year 2020 Jimmy 2020 Pandemic and Cancer - thank God for music Liv’s List XOXO by The Jayhawks Beach Bunny - Honeymoon Fetch the Bolt Cutters by Fiona Apple Phoebe Bridgers - Punisher Punisher by Phoebe Bridgers Crack Cloud - Pain Olympics Women in Music, Pt. III by HAIM Disq - Collector Song For Our Daughter by Laura Marling Fontaines D.C. - A Hero’s Death Homegrown by Neil Young Ghostpoet - I Grow Tired But Dare Not Fall Asleep Shore by Fleet Foxes Freddie Gibbs & The Alchemist - Alfredo Beyond the Pale by Jarv Is... Lianne La Havas - Lianne La Havas My Echo by Laura Veirs Jyoti - Mama, You Can Bet! Good Souls Better Angels by Lucinda Williams Mary Lattimore - Silver Ladders Even in Exile by James Dean Bradfield Liv.E - Couldn’t Wait To Tell You… Midnight Manor by The Nude Party Agnes Obel - Myopia Sun Racket by Throwing Muses Okay Kaya - Watch This Liquid Pour Itself England Is a Garden by Cornershop Angel Olsen - Whole New Mess On Sunset by Paul Weller The Orielles - Disco Volador Reunions by Jason Isbell and the 400 Unit Protomartyr - Ultimate Success Today Alphabetland by X Rolling Blackouts Coastal Fever - Sideways To New Italy Down in the Weeds, Where the World Once Was by Bright Eyes Run The Jewels - RTJ4 Let It All In by Arboretum Slow Pulp - Moveys Sideways to New Italy by Rolling Blackouts Coastal Fever Shannon sez Squirrel Flower - I Was Born Swimming Collector by Disq Moses Sumney - græ Never Not Together by Nada Surf Bladee - 333 Tobin Sprout - Empty Horses The Unraveling -

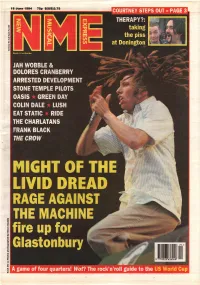

1994.06.18-NME.Pdf

INDIE 45s US 45s PICTURE: PENNIE SMITH PENNIE PICTURE: 1 I SWEAR........................ ................. AII-4-One (Blitzz) 2 I’LL REMEMBER............................. Madonna (Maverick) 3 ANYTIME, ANYPLACE...................... Janet Jackson (Virgin) 4 REGULATE....................... Warren G & Nate Dogg (Outburst) 5 THE SIGN.......... Ace Of Base (Arista) 6 DON’TTURN AROUND......................... Ace Of Base (Arista) 7 BABY I LOVE YOUR WAY....................... Big Mountain (RCA) 8 THE MOST BEAUTIFUL GIRL IN THE WORLD......... Prince(NPG) 9 YOUMEANTHEWORLDTOME.............. Toni Braxton (UFace) NETWORK UK TOP SO 4Ss 10 BACK AND FORTH......................... Aaliyah (Jive) 11 RETURN TO INNOCENCE.......................... Enigma (Virgin) 1 1 LOVE IS ALL AROUND......... ...Wet Wet Wet (Precious) 37 (—) JAILBIRD............................. Primal Scream (Creation) 12 IFYOUGO ............... ....................... JonSecada(SBK) 38 38 PATIENCE OF ANGELS. Eddi Reader (Blanco Y Negro) 13 YOUR BODY’S CALLING. R Kelly (Jive) 2 5 BABYI LOVE YOUR WAY. Big Mountain (RCA) 14 I’M READY. Tevin Campbell (Qwest) 3 11 YOU DON’T LOVE ME (NO, NO, NO).... Dawn Penn (Atlantic) 39 23 JUST A STEP FROM HEAVEN .. Eternal (EMI) 15 BUMP’N’ GRIND......................................R Kelly (Jive) 4 4 GET-A-WAY. Maxx(Pulse8) 40 31 MMMMMMMMMMMM....... Crash Test Dummies (RCA) 5 7 NO GOOD (STARTTHE DANCE)........... The Prodigy (XL) 41 37 DIE LAUGHING........ ................. Therapy? (A&M) 6 6 ABSOLUTELY FABULOUS.. Absolutely Fabulous (Spaghetti) 42 26 TAKE IT BACK ............................ Pink Floyd (EMI) 7 ( - ) ANYTIME YOU NEED A FRIEND... Mariah Carey (Columbia) 43 ( - ) HARMONICAMAN....................... Bravado (Peach) USLPs 8 3 AROUNDTHEWORLD............... East 17 (London) 44 ( - ) EASETHEPRESSURE................... 2woThird3(Epic) 9 2 COME ON YOU REDS 45 30 THEREAL THING.............. Tony Di Bart (Cleveland City) 3 THESIGN.,. Ace Of Base (Arista) 46 33 THE MOST BEAUTIFUL GIRL IN THE WORLD. -

Palmarès Musicaux 2020

Bilan musical 2020 Les palmarès Pour la 13 ème année (espérons que ce nombre nous porte chance) nous avons le très grand plaisir de vous présenter les palmarès publiés dans les magazines musicaux (Les Inrockuptibles, Magic, Jazz Magazine, FrancoFans, Rolling Stone, Classica, Diapason & Télérama), les webzines de qualité (CitizenJazz, ResMusica) et les sites Internet que nous consultons assidûment (Allmusic, Metacritic & Any Decent Music?), qui compilent les notes données par les rédacteurs de dizaines de magazines et webzines de langue anglaise. Médiathèque Etienne Caux ● Espace Musique 6 rue Lechat, Saint -Nazaire • Renseignement : 02 44 73 45 60 Allmusic : Fondé en 1991 par l’archiviste américain Michael Erlewine, Allmusic (ou AMG) est certainement la base de données (critique) la plus généraliste du web, puisqu’elle traite de tous les genres musicaux (classique, jazz, pop rock, électro, hip hop, musiques du mondes…etc) : une référence incontournable pour tous les amateurs de musiques. 1- AC/DC – Power Up 2- Algiers – There Is No Year 3- Angel Olsen – Whole New Mess 4- Bach Choir/David Hill: Howells – Missa Sabrinensis 5- Angelica Garcia – Cha Cha Palace 6- Bad Bunny – YHLQMDLG 7- BC Camplight – Shortly After Takeoff 8- Beatrice Dillon – Workaround 9- Bob Dylan – Rough and Rowdy Ways 10- Bob Mould – Blue Hearts 11- Boldy James & Sterlling Toles – Manger on McNichols 12- Brandy – B7 13- Brandy Clark – Your Life Is a Record 14- Brothers Osborne – Skeletons 15- Carolyn Sampson/Osmo Vänskä/Minnesota Orchestra – Mahler 4 16- Childish Gambino – 3.15.2020 17- Chloe x Halle – Ungodly Hour 18- Christian Sands – Be Water 19- Cleo Sol – Rose in the Dark (digital) 20- Cornershop – England Is a Garden 21- Creeper – Sex, Death & the Infinite Void 22- Deftones – Ohms 23- Dua Lipa – Future Nostalgia 24 - Edward Gardner/City of Birmingham Symphony Orch.: Schubert, vol. -

Longlist 4/2020 Vom Preis Der Deutschen Schallplattenkritik E.V

Longlist 4/2020 vom Preis der deutschen Schallplattenkritik e.V. Veröffentlicht: 15. Oktober 2020 Der Preis der deutschen Schallplattenkritik stellt die aktuelle Longlist 4.2020 vor. Die zurzeit 154 Kritiker-Juroren haben in 32 Kategorien insgesamt 232 Neuerscheinungen des letzten Quartals nominiert, die für die nächste Bestenliste in Frage kommen. Die Bestenliste 4/2020 wird am 16. November veröffentlicht. Longlist Jury Orchestermusik Beethoven: Symphonien Nr. 1-5. Le Concert des Nations, Savall (Alia Vox) Beethoven: Symphonie Nr. 9; Chorfantasie. Karg, Güra u.a. FBO, Heras-Casado (harmonia mundi) Beethoven, Barry: Symphonien Nr. 1-3 u.a. Stone, Hodges, Britten Sinfonia, Adès (Signum) Brahms: Symphonien Nr. 1-4. Wiener Symph, Jordan (Wiener Symphoniker) Mahler: Das Lied von der Erde. Richardot, Saelens, Het Collectief, de Leeuw (Alpha) Mayer: Symphonien Nr. 1 & 2. NDR Radiophil Hannover, McFall (cpo) Rott: Orchesterwerke Vol. 1. Gürzenich-O, Ward (Capriccio) Schreker: Orchesterwerke Vol. 1. Bochumer Symph, Sloane (cpo) Schumann: Symphonien Nr. 1 & 4. Gürzenich-O, Roth (myrios) Jury Konzerte „Concertos 4 Violins“ – Werke von Vivaldi u.a. Hirasaki, Sato u.a., Concerto Köln (Berlin Classics) „Transitions“ – Cellokonzerte von Kapustin & Schnittke. Runge, RSB, Strobel (Capriccio) Beethoven: Klavierkonzerte Vol.2. Bezuidenhout, FBO, Heras-Casado (harmonia mundi) Nielsen, Lindberg: Klarinettenkonzerte. Manz, Deutsche Radio Phil, Beykirch (Berlin Classics) G Prokofjew: Cellokonzert u.a., Mr.Switch, Adrianov, Ural Philharmonic O, Bogorad (Signum) Schostakowitsch: Cellokonzerte Nr. 1 & 2. Gerhardt, WDR SO, Saraste (Hyperion) Jury Kammermusik I „A Journey For Two“ – Werke von Xenakis, Kodály, Honegger, Skalkottas. Kadesha, Hunter (CAvi) „Love and Death“ – Werke von Schubert, Turina, Kurtág u.a.. Navarra String Q (Orchid) „Paris – Moscou“ – Werke von Haydn, Tanejew, Françaix u.a. -

A-570-053 Investigation Public Document E&C VI: MJH/TB MEMORANDUM FOR: Gary Taverman Deputy Assistant Secretary for Antid

A-570-053 Investigation Public Document E&C VI: MJH/TB MEMORANDUM FOR: Gary Taverman Deputy Assistant Secretary for Antidumping and Countervailing Duty Operations, performing the non-exclusive functions and duties of the Assistant Secretary for Enforcement and Compliance THROUGH: P. Lee Smith Deputy Assistant Secretary for Policy and Negotiations James Maeder Senior Director, performing the duties of the Deputy Assistant Secretary for AD/CVD Operations Robert Heilferty Acting Chief Counsel for Trade Enforcement and Compliance Albert Hsu Senior Economist, Office of Policy FROM: Leah Wils-Owens Office of Policy, Enforcement & Compliance DATE: October 26, 2017 SUBJECT: China’s Status as a Non-Market Economy Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................................ 4 INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND ................................................................................... 8 SUMMARY OF COMMENTS FROM PARTIES......................................................................... 9 ANALYSIS ................................................................................................................................... 11 Factor One: The extent to which the currency of the foreign country is convertible into the currency of other countries. .......................................................................................................... 12 A. Framework of the Foreign Exchange Regime ................................................................ 12 -

Protomartyr Announce New Album & North American

March 11, 2020 For Immediate Release PROTOMARTYR ANNOUNCE NEW ALBUM & NORTH AMERICAN TOUR, SHARE NEW MUSIC VIDEO ULTIMATE SUCCESS TODAY OUT 5/29 ON DOMINO WATCH VIDEO FOR “PROCESSED BY THE BOYS” (photo credit: Trevor Naud) Today Protomartyr announces their fifth album, Ultimate Success Today, out May 29th on Domino. Following the release of Relatives In Descent, the band’s critically acclaimed headlong dive into the morass of American life in 2017 (featured on myriad “best of” lists, including The New York Times, Esquire, Newsweek, and more), Ultimate Success Today continues to further expand the possibilities of what a Protomartyr album can sound like. Along with today’s album announcement, the band shares the video for their first single “Processed By The Boys,” and announces a summer North American tour. WATCH THE VIDEO FOR “PROCESSED BY THE BOYS” http://smarturl.it/PBTBYT LISTEN TO “PROCESSED BY THE BOYS” http://smarturl.it/PBTBStrm PRE-ORDER ULTIMATE SUCCESS TODAY Domino Mart | Digital “There is darkness in the poetry of Ultimate Success Today,” says punk legend, founding member of the Raincoats, and friend of the band Ana da Silva. “The theme of things ending, above all human existence, is present and reminiscent of Cormac McCarthy’s The Road. Our world has reached a point that makes us afraid: fires, floods, earthquakes, hunger, war, intolerance…There are cries of despair. Is there hope? Greed is the sickness that puts life in danger.” "The re-release of our first album had me thinking about the passage of time and its ultimate conclusion,” says singer Joe Casey of Ultimate Success Today. -

Longlist 1/2020 Vom Preis Der Deutschen Schallplattenkritik E.V

Longlist 1/2020 vom Preis der deutschen Schallplattenkritik e.V. Jury Orchestermusik Beethoven; R Strauss: Symphonie Nr. 3; Metamorphosen. Sinfonia Grange au Lac, Salonen (Alpha) Beethoven: Symphonie Nr. 9. Kampe, Sindram u.a., Wiener Singverein, Wiener Symph, Jordan (Sony) Bruckner: Symphonie Nr. 6. London SO, Rattle (LSO live) Bruckner: Symphonien Nr. 4 & 7. Staatskapelle Dresden, Blomstedt (MDG) Eisler: Leipziger Symphonie u.a. MDR SO, Kammersymphonie Berlin, Bruns (Capriccio) Ives: Symphonien Nr. 3 & 4. Dugan, San Francisco SO, Thomas (SFS Media) Messiaen: L’Ascension, Le Tombeau Resplendissant u.a. Tonhalle O Zürich, Järvi (Alpha) Schostakowitsch: Symphonie Nr. 10. SO des BR, Jansons (BR Klassik) Schubert: Symphonie Nr. 9. Scottish Chamber O, Emelyanychev (Linn) Schumann: Symphonien Nr. 2 & 4 u.a. London SO, Gardiner (LSO live) Schumann: Symphonien Nr. 2 & 4. Antwerp SO, Herreweghe (Phi) Jury Konzerte „Time & Eternity“ – Werke von Zorn, Hartmann u.a. Kopatchinskaja, Camerata Bern (Alpha) JS Bach: Violinkonzerte. Debretzeni, English Baroque Soloists, Gardiner (SDG) Bartók: Violinkonzert Nr. 2, Rhapsodien 1 & 2. Skride, WDR SO, Aadland (Orfeo) Beethoven: Klavierkonzerte Nr. 1-5. Brautigam, Kölner Akademie, Willens (BIS) Beethoven: Klavierkonzerte Nr. 1-5. Liesicki, Academy of St Martin in the Fields (DG) Brahms: Klavierkonzert Nr. 1, Vier Balladen. Royal Northern Sinfonia, Vogt (Ondine) Dvořák, Khachaturian: Violinkonzerte. Barton Pine, Royal Scottish National O, Abrams (Avie) G Prokofiev: Saxophonkonzert u.a. Marsalis, Burgess, Ural Philharmonic, Bogorad (Signum) Rachmaninoff: Klavierkonzerte Nr. 1 & 3. Trifonov, Philadelphia O, Nézet-Séguin (DG) Schumann, Brahms: Konzerte. Weithaas, Hornung, NDR Radiophil, Manze (cpo) Jury Kammermusik I „Beethoven around the World: Vienna“ – Streichquartette. Q Ébène (Erato) „Souvenirs“ – Werke von Tschaikowski. -

Imposer Nos Urgences Sanitaires, Économiques Et Antiracistes

n°533 | 3 septembre 2020 — 1,50 € l’hebdomadaire du NPA ~ .NPA. Santé publique en danger, casse sociale, répression... Imposer nos urgences sanitaires, économiques et antiracistes ÉDITO ACTU INTERNATIONALE Dossier Des valeurs toujours Liban : le système politique plus rances néolibéral et confessionnel 12e UNIVERSITÉ Page 2 en question Page 5 PREMIER PLAN SOUSCRIPTION 2020 Covid-19 : le gouvernement Contre le retour à l’anormal, D'ÉTÉ DU NPA a toujours un temps de retard soutenez le NPA ! Pages 6 et 7 sur le virus Page 2 Page 12 02 | Premier plan À la Une édito SANTÉ PUBLIQUE EN DANGER, CASSE SOCIALE, RÉPRESSION... Par JULIEN SALINGUE Des valeurs toujours Imposer nos urgences sanitaires, plus rances économiques et antiracistes insi donc, en France, en 2020, un « journal » a cru bon de mettre en scène une députée noire sous les Depuis le déconfinement le 11 mai, le Covid-19 n’a pas cessé de circuler en France, comme Urgence antiraciste Atraits d’une esclave. Si les guillemets dans le reste du monde. L’été s’est passé sous le signe de l’incitation permanente à Assurer notre protection sanitaire s’imposent, tant Valeurs actuelles n’est en « vivre », c’est-à-dire, pour ceux qui prétendent nous gouverner, consommer, pour « relancer et économique, c’est aussi com- réalité rien d’autre qu’un torchon d’extrême battre toutes les inégalités qui se droite, force est toutefois de constater que l’économie ». Mais ni le remaniement gouvernemental ni les centaines de milliards injectés maintiennent par des rapports d’op- le torchon en question a pignon sur rue et aux entreprises n’empêchent de se trouver début septembre devant la vérité sans fard. -

Harm Reduction in the Time of Covid

FREE. WEEKLY. VOLUME 75—ISSUE 05—OCT. 8, 2020 LIBRARY SECURITY COMES THE UPS AND DOWNS OF RWB DANCES AT A DISTANCE—P3 DOWN—P11 DIAGNOSES—P15 HARM REDUCTION IN THE TIME OF COVID UNIVERSITY OF WINNIPEG AND DOWNTOWN COMMUNITY NEWSPAPER ON THE COVER Arts and culture editor Beth Schellenberg looks at how the COVID-19 pandemic has impacted Winnipeg's ongoing overdose crisis. Read more on page 7. STRIFE OF BRIAN THOMAS PASHKO @THOMASPASHKO MANAGING EDITOR This week’s cover feature, by arts and culture editor Beth Schellenberg, ex- amines how the COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated Manitoba’s overdose crisis. But longtime readers of The Uniter will recognize that this crisis didn’t start with COVID. Since Brian Pallister’s election in 2016, The Uniter has been examining how the premier’s approach to health- care and drug policy has wreaked hav- oc on all Manitobans, especially those who use drugs. Whether it’s his opposition to safe-in- jection sites, his moralizing tone or his emphasis on policing over access to care, Pallister has taken every possible opportunity to further criminalize some of the most vulnerable Manitobans. It’s upsetting, but not surprising. It’s entirely in line with his overarching approach to governance, which almost always sub- stitutes compassion with cruelty. His and his government’s callous positions on COVID aid have severely affected Manitobans at risk of overdos- ing, leaving community organizations to pick up the slack. But his disastrous handling of the pandemic has only worsened the deep and long-running problems he’s created. -

LIJSTJES!!! Zoals Ieder Jaar Is Het Aan Het Einde Van Het Jaar LIJSTJES Tijd! Dus Ook Dit Jaar Vragen We Jou Wat Jij De Beste 10 Albums Van Het Jaar Vind

LIJSTJES!!! Zoals ieder jaar is het aan het einde van het jaar LIJSTJES tijd! Dus ook dit jaar vragen we jou wat jij de beste 10 albums van het jaar vind. Extra vermeldingen zijn altijd welkom, zoals bijvoorbeeld: Beste Concert van het jaar….dit jaar mogen streamingsconcerten ook genoemd worden, anders blijft er bar weinig over ;) , live plaat van het jaar, onderzetter van het jaar, single van het jaar enzovoorts... Let Op!! De albums in je TOP10 moeten uit 2020 komen, het mogen geen heruitgaven, verzamel albums of live albums zijn! Graag zien we jou lijstje tegemoet, het liefst handgeschreven (!) bij ons ingeleverd uiterlijk zaterdag 19 december. Alle lijstjes worden opgehangen in de winkel en onder de inzenders verloten wij een fijn presentje! Om alvast een beetje geïnspireerd te raken hieronder onze lijstjes: Patricia Helma 1. Fontaines DC – A Hero’s Death 1. Eefje de Visser – Bitterzoet 2. Idles – Ultra Mono 2. Khruangbin – Mordechai 3. Molchat Doma – Etazhi 3. Fontaines DC – A Hero’s Death 4. Protomartyr – Day Without End 4. Frazey Ford – U Kin B The Sun 5. Working Men’s Club – WMC 5. Matt Berninger – Serpentine Prison 6. Car Seat Headrest – Making A Door Less Open 6. Eels – Earth To Dora 7. Other Lives – For Their Love 7. Spinvis – 7.6.9.6 8. Tame Impala – The Slow Rush 8. Black Pumas – Black Pumas 9. Elvis Costello – Hey Clockface 9. Tame Impala – Slow Rush 10. Parcels? – Live Vol. 1 10. Gorillaz – Song Machine, Season 1 Beste NLplaat: Eefje de Visser – Bitterzoet Prachtig live optreden: Lowlands – Eefje de Visser Beste LIVEplaat: Fijne single: 1. -

Worm in Heaven”

April 28, 2020 For Immediate Release PROTOMARTYR RELEASE NEW SINGLE/VIDEO, “WORM IN HEAVEN” ULTIMATE SUCCESS TODAY GETS NEW JULY 17TH RELEASE DATE ON DOMINO Photo Credit: Trevor Naud Today, Protomartyr present a new single/video, “Worm In Heaven,” off of their forthcoming album, Ultimate Success Today, which has had its release date moved to July 17th, out on Domino. Additionally, Protomartyr must sadly cancel their scheduled 2020 tour dates. Ticket buyers should seek refunds at the point of purchase. The band looks forward to bringing these songs on the road as soon as safely possible. Following lead single “Processed By The Boys,” “Worm In Heaven” winds with meandering guitar, mellow drums, and Joe Casey’s consuming voice: “I am a worm in heaven / so close to grace / could lick it off of the boot heels of the blessed.” Eventually, the track rises with crashing instrumentation and a repeated refrain. The accompanying video, directed by Trevor Naud, is a collection of abstract still images stitched together. It was inspired by the 1962 Chris Marker short film La Jetée and was shot using limited resources, mainly a 35mm film camera, with no film crew. As the video goes on, the images grow stranger and more off-putting. “The idea is a sort of dream chamber that has lured its creator into a near-constant state of isolation,” says director Trevor Naud. “She lives out her days trapped as the sole subject of her own experiment: the ability to simulate death. It is like a drug to her. Everything takes place in a small, claustrophobic environment.