An Updated Review of Dendrochronological Investigations in Mexico, a Megadiverse Country with a High Potential for Tree-Ring Sciences

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Blue Intensity for Dendroclimatology: Should We Have the Blues?

Dendrochronologia 32 (2014) 191–204 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Dendrochronologia jou rnal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/dendro ORIGINAL ARTICLE Blue intensity for dendroclimatology: Should we have the blues? Experiments from Scotland a,∗ b c c Milosˇ Rydval , Lars-Åke Larsson , Laura McGlynn , Björn E. Gunnarson , d d a Neil J. Loader , Giles H.F. Young , Rob Wilson a School of Geography and Geosciences, University of St Andrews, UK b Cybis Elektronik & Data AB, Saltsjöbaden, Sweden c Department of Physical Geography and Quaternary Geology, Stockholm University, Stockholm, Sweden d Department of Geography, Swansea University, Swansea, UK a r t i c l e i n f o a b s t r a c t Article history: Blue intensity (BI) has the potential to provide information on past summer temperatures of a similar Received 1 April 2014 quality to maximum latewood density (MXD), but at a substantially reduced cost. This paper provides Accepted 27 April 2014 a methodological guide to the generation of BI data using a new and affordable BI measurement sys- tem; CooRecorder. Focussing on four sites in the Scottish Highlands from a wider network of 42 sites Keywords: developed for the Scottish Pine Project, BI and MXD data from Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris L.) were used Blue intensity to facilitate a direct comparison between these parameters. A series of experiments aimed at identify- Maximum latewood density ing and addressing the limitations of BI suggest that while some potential limitations exist, these can Scots pine Dendroclimatology be minimised by adhering to appropriate BI generation protocols. The comparison of BI data produced using different resin-extraction methods (acetone vs. -

Encino En Guadalupe Y Calvo, Chihuahua Diversity and Vertical

Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Forestales Vol. 10 (53) May – June (2019) DOI: https://doi.org/10.29298/rmcf.v10i53.173 Article Diversidad y estructura vertical del bosque de pino– encino en Guadalupe y Calvo, Chihuahua Diversity and vertical structure of the pine-oak forest in Guadalupe y Calvo, Chihuahua Samuel Alberto García García1, Raúl Narváez Flores1, Jesús Miguel Olivas García1 y Javier Hernández Salas1 Resumen Se evaluaron áreas con y sin manejo forestal de la Umafor 0808 Guadalupe y Calvo, Chihuahua; gestionadas mediante el Método Mexicano de Ordenación de Bosques Irregulares (MMOBI). Se analizó y comparó la información de conglomerados del Inventario Nacional Forestal y de Suelos (2004-2009); 95 en masas con manejo y 27 sin manejo. Se determinó la estructura vertical por medio de la regeneración natural, pisos de altura de los árboles y posición sociológica. Las especies con distribución continua, desde el piso inferior de la regeneración hasta el piso arbóreo superior en el bosque con manejo fueron: Pinus durangensis, P. arizonica, P. ayacahuite, P. herrerae y P.engelmannii; mientras que, en el bosque sin manejo se registraron: P. durangensis y P. arizonica. Las principales diferencias entre los bosques estudiados correspondieron al promedio de altura en el piso arbóreo superior; en los bosques con manejo fue de 30.16 m y en los sin manejo, su valor fue de 21.86 m; además, se observó una mayor regeneración de P. durangensis en los primeros. Respecto a la diversidad de especies, no hubo diferencia significativa entre ambos tipos de bosque (P>0.05). Por lo anterior, se concluye que, de acuerdo con la información analizada, la regulación del aprovechamiento maderable con el MMOBI permite mantener la diversidad estructural y de especies, similar a la de un bosque natural sin manejo. -

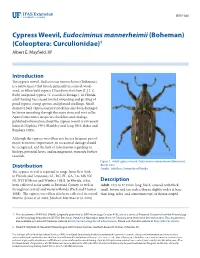

Cypress Weevil, Eudociminus Mannerheimii (Boheman) (Coleoptera: Curculionidae)1 Albert E

EENY-360 Cypress Weevil, Eudociminus mannerheimii (Boheman) (Coleoptera: Curculionidae)1 Albert E. Mayfield, III2 Introduction The cypress weevil, Eudociminus mannerheimii (Boheman), is a native insect that breeds primarily in scarred, weak- ened, or fallen bald cypress (Taxodium distichum [L.] L.C. Rich) and pond cypress (T. ascendens Brongn.). In Florida, adult feeding has caused limited wounding and girdling of pond cypress stump sprouts and planted seedlings. Small diameter bald cypress nursery stock has also been damaged by larvae tunneling through the main stem and root collar. Apart from entries in species checklists and catalogs, published information about the cypress weevil is extremely limited (Hopkins 1904, Blatchley and Leng 1916, Baker and Bambara 1999). Although the cypress weevil has not been a frequent pest of major economic importance, its occasional damage should be recognized, and the lack of information regarding its biology, potential hosts, and management, warrants further research. Figure 1. Adult cypress weevil, Eudociminus mannerheimii (Boheman), dorsal view. Distribution Credits: Lyle Buss, University of Florida The cypress weevil is reported to range from New York to Florida and Louisiana (AL, DC, FL, GA, LA, MS, NC, NJ, NY) (O’Brien and Wimber 1982). In Florida, it has Description been collected as far south as Broward County, as well as Adult: 10.5 to 17.0 mm long; black, covered with thick, throughout central and western Florida (Peck and Thomas small, brown and tan scales; thorax slightly wider at base 1998). The cypress weevil has also been collected in central than long; sides (and sometimes top) of thorax striped Mexico (Jones et al. -

Pinus Pinceana Gordon in Response to Soil Moisture

From Forest Nursery Notes, Winter 2012 232. Root growth in young plants of Pinus pinceana Gordon in response to soil moisture. Cordoba-Rodriguez, D., Vargas-Hernandez, J. J., Lopez-Upton, J., and Munoz-Orozco, A. Agrociencia 45:493-506. 2011. CRECIMIENTO DE LA RAÍZ EN PLANTAS JÓVENES DE Pinus pinceana Gordon EN RESPUESTA A LA HUMEDAD DEL SUELO ROOT GROWTH IN YOUNG PLANTS OF Pinus pinceana Gordon IN RESPONSE TO SOIL MOISTURE Diana Córdoba-Rodríguez1, J. Jesús Vargas-Hernández1*, Javier López-Upton1, Abel Muñoz-Orozco2 1Posgrado Forestal, 2Posgrado en Recursos Genéticos y Productividad, Campus Montecillo, Colegio de Postgraduados. 56230. Carretera México-Texcoco, km 36.5. Montecillo, Estado de México, México. ([email protected]). Resumen AbstRAct Pinus pinceana Gordon es un pino piñonero endémico de Pinus pinceana Gordon is an endemic pinyon pine of México México que crece en condiciones semiáridas, en poblacio- that grows in semiarid conditions, in isolated populations, nes aisladas, a lo largo de la Sierra Madre Oriental. Con el along the Sierra Madre Oriental. In order to identify root propósito de identificar características de la raíz asociadas a traits associated with mechanisms of adaptation to water mecanismos de adaptación ante condiciones de estrés hídri- stress conditions, the growth and root morphology in co, se evaluó el crecimiento y morfología de la raíz en dos two soil moisture conditions were evaluated in plants of condiciones de humedad del suelo, en plantas de seis pobla- six populations of the species representing a geographical ciones de la especie que representan un gradiente geográfico gradient of aridity. The study was conducted on 3-year- de aridez. -

Dendrochronology, Fire Regimes

Encyclopedia of Scientific Dating Methods DOI 10.1007/978-94-007-6326-5_76-4 # Springer Science+Business Media Dordrecht 2013 Dendrochronology, Fire Regimes Peter M. Brown* Rocky Mountain Tree-Ring Research, Inc., Fort Collins, CO, USA Definition Use of tree-ring data and methods to reconstruct past fire timing, fire regimes, and fire effects on individuals, communities, and ecosystems. Introduction Fire directly or indirectly affects woody plants in many ways, some of which will leave evidence in age or growth patterns in individual trees or community structure that can be cross-dated using dendrochronological methods. This evidence can be used to reconstruct past fire dates, fire regimes, and fire effects on individuals, communities, and ecosystems (“pyrodendroecology”). Fire regimes are defined as the combination of fire frequency, severity, size, seasonality, and relationships with forcing factors such as climate or changes in human land use. Fire Evidence in Trees and Community Structure A common type of fire evidence is from severe fire that kills all or most trees in an area which opens up space for new trees to establish. Even-aged forest structure is often used as evidence of past lethal fire, also referred to as “stand-replacing” fire. Such evidence provides a minimum date for the fire (i.e., the fire occurred sometime before the innermost dates of the oldest trees), and, by sampling multiple stands in an area, estimates of the fire size can be made based on broader- scale patterns of tree ages. Conversely, multiaged structure is considered to be evidence of less severe fires or other patchy mortality and recruitment events. -

Redalyc.ESTUDIO FLORÍSTICO DE LOS PIÑONARES DE PINUS

Acta Botánica Mexicana ISSN: 0187-7151 [email protected] Instituto de Ecología, A.C. México Villarreal Quintanilla, José Ángel; Mares Arreola, Oscar; Cornejo Oviedo, Eladio; Capó Arteaga, Miguel A. ESTUDIO FLORÍSTICO DE LOS PIÑONARES DE PINUS PINCEANA GORDON Acta Botánica Mexicana, núm. 89, octubre, 2009, pp. 87-124 Instituto de Ecología, A.C. Pátzcuaro, México Disponible en: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=57412083007 Cómo citar el artículo Número completo Sistema de Información Científica Más información del artículo Red de Revistas Científicas de América Latina, el Caribe, España y Portugal Página de la revista en redalyc.org Proyecto académico sin fines de lucro, desarrollado bajo la iniciativa de acceso abierto Acta Botanica Mexicana 89: 87-124 (2009) ESTUDIO FLORÍSTICO DE LOS PIÑONARES DE PINUS PINCEANA GORDON JOSÉ ÁNGEL VILLARREAL QUINTANILLA , OSCAR MARES ARREOLA , ELADIO CORNE J O OV IEDO Y MIGUEL A. CAPÓ ARTEAGA Universidad Autónoma Agraria Antonio Narro, Departamento de Botánica y Departamento Forestal, 25315 Buenavista Saltillo, Coahuila, México. [email protected]; [email protected] RESUMEN Se presenta un estudio de la flora de 14 comunidades con Pinus pinceana Gordon. Esta especie forma pequeños bosques aislados a lo largo de la Sierra Madre Oriental, en el norte y centro de México. Se realizó un análisis de similitud florística entre las localidades estudiadas. Se reportan 446 especies, más 4 taxa infraespecíficas adicionales, distribuidas en 247 géneros y 78 familias. De acuerdo con su composición florística, las comunidades estudiadas se pueden separar en dos conjuntos: las más norteñas, localizadas en Coahuila, Zacatecas y San Luis Potosí, y las de la región sur en Querétaro e Hidalgo. -

Diversifying Tree Choices for a Shadier Future

Diversifying Tree Choices for a Shadier Future Adam Black Director, Peckerwood Garden Hempstead TX With special cameo appearance by Dr. David Creech Dr. David Creech Who is this guy? • Former horticulturist at Kanapaha Botanial Gardens, Gainesville FL • Managed Forest Pathology and Forest Entomology labs at University of Florida • Former co-owner of Xenoflora LLC (rare plant mail- order nursery) • Current Director of Peckerwood Garden, Hempstead, Texas Tree Diversity in Landscapes Advantages of diverse tree assemblages • Include many plant families attracts biodiversity (pollinators, predators, etc) that all together reduce pest problems • Diversity means loss is minimal if a new disease targets a particular genus. • Generate excitement and improve aesthetics • Use of locally adapted forms over mainstream selections from distant locations • Adaptations for specific conditions (salt, alkalinity, etc) • If mass plantings are necessary, use seed grown plants for genetic diversity rather than clonally propagated selections Disadvantages of diverse tree assmeblages • Hard to find among the standard issue trees available locally • Hard to convince nurseries to try something new • Initial trialing of new material, many failures among the winners • A disadvantage in some cases – non-native counterparts may be superior to natives. Diseases: • Dutch Elm Disease (Ulmus americana) • Emerald Ash Borer (Fraxinus spp.) • Laurel Wilt (Persea, Sassafras, Lindera, etc) • Crepe Myrtle Bark Scale (Lagerstroemia spp.) • Next? Quercus virginiana Quercus fusiformis Quercus fusiformis Weeping form Quercus virginiana ‘Grandview Gold’ Quercus nigra Variegated Quercus tarahumara Quercus crassifolia Quercus sp. San Carlos Mtns Quercus tarahumara Quercus laeta Quercus polymorpha Quercus germana There is one in the auction! Quercus rysophylla Quercus sinuata var. sinuata Quercus imbricaria (southern forms) Quercus glauca Quercus acutus Quercus schottkyana Quercus marlipoensis Lithocarpus edulis ‘Starburst’ Lithocarpus henryi Lithocarpus kawakamii Platanus rzedowski incorrectly offered as P. -

Native Trees of Mexico: Diversity, Distribution, Uses and Conservation

Native trees of Mexico: diversity, distribution, uses and conservation Oswaldo Tellez1,*, Efisio Mattana2,*, Mauricio Diazgranados2, Nicola Kühn2, Elena Castillo-Lorenzo2, Rafael Lira1, Leobardo Montes-Leyva1, Isela Rodriguez1, Cesar Mateo Flores Ortiz1, Michael Way2, Patricia Dávila1 and Tiziana Ulian2 1 Facultad de Estudios Superiores Iztacala, Av. De los Barrios 1, Los Reyes Iztacala Tlalnepantla, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Estado de México, Mexico 2 Wellcome Trust Millennium Building, RH17 6TN, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, Ardingly, West Sussex, United Kingdom * These authors contributed equally to this work. ABSTRACT Background. Mexico is one of the most floristically rich countries in the world. Despite significant contributions made on the understanding of its unique flora, the knowledge on its diversity, geographic distribution and human uses, is still largely fragmented. Unfortunately, deforestation is heavily impacting this country and native tree species are under threat. The loss of trees has a direct impact on vital ecosystem services, affecting the natural capital of Mexico and people's livelihoods. Given the importance of trees in Mexico for many aspects of human well-being, it is critical to have a more complete understanding of their diversity, distribution, traditional uses and conservation status. We aimed to produce the most comprehensive database and catalogue on native trees of Mexico by filling those gaps, to support their in situ and ex situ conservation, promote their sustainable use, and inform reforestation and livelihoods programmes. Methods. A database with all the tree species reported for Mexico was prepared by compiling information from herbaria and reviewing the available floras. Species names were reconciled and various specialised sources were used to extract additional species information, i.e. -

Seed Production and Quality of Pinus Durangensis Mart., from Seed Areas and a Seed Stand in Durango, Mexico

Pak. J. Bot., 46(4): 1197-1202, 2014. SEED PRODUCTION AND QUALITY OF PINUS DURANGENSIS MART., FROM SEED AREAS AND A SEED STAND IN DURANGO, MEXICO VERÓNICA BUSTAMANTE-GARCÍA1, JOSÉ ÁNGEL PRIETO-RUÍZ2,3*, ARTEMIO CARRILLO-PARRA4, REBECA ÁLVAREZ-ZAGOYA5, HUMBERTO GONZÁLEZ-RODRIGUEZ4 AND JOSÉ JAVIER CORRAL-RIVAS6 1Universidad Juárez del Estado de Durango, Doctorado Institucional en Ciencias Agropecuarias y Forestales. Durango, Durango. México. C.P. 34120 2Ex-Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones Forestales, Agrícolas y Pecuarias, Centro de Investigación Regional Norte Centro, Campo Experimental Valle del Guadiana, Durango, Durango, México. C.P. 34170 3Universidad Juárez del Estado de Durango, Facultad de Ciencias Forestales, Durango, Durango, México. C.P. 34120 4Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León, Facultad de Ciencias Forestales. Linares, Nuevo León, México. C.P. 67700 5Instituto Politécnico Nacional, CIIDIR-IPN, Unidad Durango, Durango, México. C.P. 34220 6Universidad Juárez del Estado de Durango, Instituto de Silvicultura e Industria de la Madera, Durango, Durango, México. C.P. 34120 *Corresponding author e-mail: [email protected]; Tel. and Fax: 55 6181301148 Abstract Seed productive potential, production efficiency and seed quality of seed areas of P. durange ns is Mart. from La Florida and La Campana, and from a Pericos seed stand, located in Durango state, Mexico were investigated. The productive potential, developed seeds, upper and lower infertile ovules, and aborted ovules during the first and second year of seed formation were determined. X-ray scanning was used to determine the percentage of seeds that were filled, emptied, malformed, or damaged by insects. Seed production efficiency was also determined. Speed, value and percentage of germination were determined under laboratory conditions. -

An Experimental Evaluation of Fire History Reconstruction Using Dendrochronology in White Oak (Quercus Alba)

1 An experimental evaluation of fire history reconstruction using dendrochronology in white oak (Quercus alba) Ryan W. McEwan, Todd F. Hutchinson, Robert D. Ford, and Brian C. McCarthy Abstract: Dendrochronological analysis of fire scars on tree cross sections has been critically important for understanding historical fire regimes and has influenced forest management practices. Despite its value as a tool for understanding histor- ical ecosystems, tree-ring-based fire history reconstruction has rarely been experimentally evaluated. To examine the effi- cacy of dendrochronological analysis for detecting fire occurrence in oak forests, we analyzed tree cross sections from sites in which prescribed fires had been recently conducted. The first fire in each treatment unit created a scar in at least one sample, but the overall percentage of samples containing scars in fire years was low (12%). We found that scars were cre- ated by 10 of the 15 prescribed fires, and the five undetected fires all occurred in sites where fire had occurred the previous year. Notably, several samples contained scars from known fire-free periods. In summary, our data suggest that tree-ring analysis is a generally effective tool for reconstructing historical fire regimes, although the following points of uncertainty were highlighted: (i) consecutive annual burns may not create fire scars and (ii) wounds that are morphologically indistin- guishable from fire scars may originate from nonfire sources. R6um6 : L'analyse dendrochronologique des cicatrices de feu sur des sections radiales de tronc d'arbre a it6 d'une im- portance cruciale pour comprendre les regimes des feux pass& et a influenck les pratiques d'amtnagement forestier. -

Current and Potential Spatial Distribution of Six Endangered Pine Species of Mexico: Towards a Conservation Strategy

Article Current and Potential Spatial Distribution of Six Endangered Pine Species of Mexico: Towards a Conservation Strategy Martin Enrique Romero-Sanchez * , Ramiro Perez-Miranda, Antonio Gonzalez-Hernandez, Mario Valerio Velasco-Garcia , Efraín Velasco-Bautista and Andrés Flores National Institute on Forestry, Agriculture and Livestock Research, Progreso 5, Barrio de Santa Catarina, Coyoacan, 04010 Mexico City, Mexico; [email protected] (R.P.-M.); [email protected] (A.G.-H.); [email protected] (M.V.V.-G.); [email protected] (E.V.-B.); fl[email protected] (A.F.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +52-553-626-8698 Received: 24 October 2018; Accepted: 6 December 2018; Published: 12 December 2018 Abstract: Mexico is home to the highest species diversity of pines: 46 species out of 113 reported around the world. Within the great diversity of pines in Mexico, Pinus culminicola Andresen et Beaman, P. jaliscana Perez de la Rosa, P. maximartinenzii Rzed., P. nelsonii Shaw, P. pinceana Gordon, and P. rzedowskii Madrigal et M. Caball. are six catalogued as threatened or endangered due to their restricted distribution and low population density. Therefore, they are of special interest for forest conservation purposes. In this paper, we aim to provide up-to-date information on the spatial distribution of these six pine species according to different historical registers coming from different herbaria distributed around the country by using spatial modeling. Therefore, we recovered historical observations of the natural distribution of each species and modelled suitable areas of distribution according to environmental requirements. Finally, we evaluated the distributions by contrasting changes of vegetation in the period 1991–2016. -

Songbird Ecology in Southwestern Ponderosa

This file was created by scanning the printed publication. Errors identified by the software have been corrected; however, some errors may remain. Chapter 1 Ecology of Southwestern Ponderosa Pine Forests William H. Moir, Brian Geils, Mary Ann Benoit, and Dan Scurlock describes natural and human induced changes in the com- What Is Ponderosa Pine Forest position and structure of these forests. and Why Is It Important? Forests dominated by ponderosa pine (Pinus ponderosa Paleoecology var. scopulorurn) are a major forest type of western North America (figure 1; Steele 1988; Daubenmire 1978; Oliver and Ryker 1990). In this publication, a ponderosa pine The oldest remains of ponderosa pine in the Western forest has an overstory, regardless of successional stage, United States are 600,000 year old fossils found in west dominated by ponderosa pine. This definition corresponds central Nevada. Examination of pack rat middens in New to the interior ponderosa pine cover type of the Society of Mexico and Texas, shows that ponderosa pine was absent American Foresters (Eyre1980). At lower elevations in the during the Wisconsin period (about 10,400 to 43,000 years mountainous West, ponderosa pine forests are generally ago), although pinyon-juniper woodlands and mixed co- bordered by grasslands, pinyon-juniper woodlands, or nifer forests were extensive (Betancourt 1990). From the chaparral (shrublands). The ecotone may be wide or nar- late Pleistocene epoch (24,000 years ago) to the end of the row, and a ponderosa pine forest is recognized when the last ice age (about 10,400 years ago), the vegetation of the overstory contains at least 5 percent ponderosa pine (USFS Colorado Plateau moved southward or northward with 1986).