Measuring the Information Society Report Volume 1 2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Postpay Roaming Tariff

Postpay Roaming Tariff Sr.No Country Live Operators Incoming Call Local Outgoing Call Call To Pakistan Call Rest of World SMS 1 Afghanistan Etisalat 0.70 0.63 1.90 Variable 0.50 2 Afghanistan AWCC/Areeba/Roshan 0.89 0.65 1.90 4.60 0.50 3 Albania AMC 0.75 0.55 3.40 3.45 0.50 4 Algeria Orascom (Djezzy)/Wataniya 1.68 1.38 4.03 4.03 0.50 5 Argentina Claro 1.03 0.75 4.00 3.97 0.50 6 Armenia Viva Cell /Armentel/Orange 0.75 0.92 4.00 3.74 0.50 7 Australia Vodafone 1.03 0.75 4.50 5.41 0.50 8 Austria Orange/T Mobile 1.41 1.10 3.30 3.45 0.50 9 Azerbaijan Azercell Telecom/Azerfone 0.75 0.60 4.30 4.31 0.50 10 Bahrain Viva/Zain/Batelco 1.79 1.15 3.74 4.60 0.50 11 Bangladesh Banglalink/Grameen Phone/Warid/Aktel 0.96 0.92 2.59 2.88 0.50 12 West Indies Cable & Wireless 1.39 0.75 3.05 Variable 0.50 13 Belarus MDC Velcom/MTS 0.93 0.45 6.00 6.00 0.50 14 Belgium Kpn Orange Base/Belgacom/Mobistar 1.16 1.00 4.20 4.20 0.50 15 Benin Atlantique Telecom 0.77 0.65 1.00 3.80 0.50 16 Bhutan B Mobile 1.93 1.60 2.60 3.45 0.50 17 Bosnia BH Telecom 0.94 0.40 2.90 2.93 0.50 18 Brazil TIM /Telemig(Vivo)/Brazil Telecom 1.04 0.90 3.00 3.45 0.50 19 Brunei DST 0.61 0.40 4.03 4.03 0.50 20 Bulgaria BTC Mobile/Globul Cosmo 1.67 0.75 5.11 4.60 0.50 21 Burkina Faso CELTEL 0.72 0.75 3.50 2.88 0.50 22 Cambodia Metfone (Viettel)/CAMGSM 1.05 0.50 2.00 4.60 0.50 23 Canada Rogers Wireless/Bell/Tellus 1.32 1.31 2.72 5.75 0.50 24 China Unicom 0.99 0.99 2.65 4.03 0.50 25 Congo, Democratic Republic Vodacom 1.95 1.38 3.45 2.88 0.50 26 Croatia T Mobile/Tele 2 2.48 1.30 4.20 3.45 0.50 27 Cyprus -

An Overview of Today's and Tomorrow's M- Commerce In

AN OVERVIEW OF TODAY’S AND TOMORROW’S M- COMMERCE IN THE NETHERLANDS AND EUROPE Hong-Vu Dang BMI Paper AN OVERVIEW OF TODAY’S AND TOMORROW’S M- COMMERCE IN THE NETHERLANDS AND EUROPE Hong-Vu Dang BMI Paper Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam Faculty of Sciences Business Mathematics and Informatics De Boelelaan 1081a 1081 HV Amsterdam www.few.vu.nl August 2006 PREFACE A part of the masters programme of the study that I am following, Business Mathematics & Informatics (BMI) at the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, is writing a BMI paper. In this paper a problem in the field of BMI is assessed using existing literature. The subjects addressed in this paper are the past, present and future developments of the relatively new phenomenon called m-commerce. Developments discussed will be from a technological perspective as well as a business perspective. I would like to express my gratitude to Dr. S. Bhulai of the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam for his guidance while I was writing this paper. Hong-Vu Dang BMI paper: An Overview Of Today’s And Tomorrow’s M-Commerce In The Netherlands And Europe ABSTRACT This paper explains: • What m-commerce is: in a nutshell, it is commerce using a mobile device such as a hand-held device or a smart phone; • What it is used for: currently, m-commerce in Europe mainly consists of messaging, such as SMS, and mobile entertainment (think of ringtones, wallpapers, and mobile games); • What technology is involved with m-commerce: this paper describes the history and future of mobile networks from 1G to 3G, and how other technologies can be used for m-commerce such as GPS, and Wi-Fi; • The business aspects of m-commerce: how much does it cost to enable m- commerce (for instance the costs of the European UMTS network) and how much turnover is made. -

International SMS - Supporting Destinations and Network Operators* 國際短訊服務 - 支援地方及網絡商*

International SMS - Supporting Destinations and Network Operators* 國際短訊服務 - 支援地方及網絡商* Destinations 地 方 Network Operator 網 絡 商 Afghanistan 阿富汗 MTN Afghanistan (Areeba) AWCC Roshan (TDCA) Aland 奧蘭島 (芬) Alands Telekommunikation Elisa Finland Sonera Albania 阿爾巴尼亞 AMC Eagle Mobile Vodafone Albania Algeria 亞爾及利亞 Djezzy Wataniya Algeria Andorra 安道爾 Andorra Telecom Angola 安哥拉 Unitel Angola Anguilla (West Indies) 安圭拉島 (西印度群島) C&W (West Indies) Digicel Antigua (West Indies) 安提瓜 (西印度群島) C&W (West Indies) Digicel Argentina 阿根廷 AMX (Claro Argentina) Movistar Argentina Telecom Personal Armenia 亞美尼亞 ArmenTel Vivacell-MTS Aruba 阿魯巴 SETAR Digicel Australia 澳洲 'yes' Optus Telstra Vodafone Australia Austria 奧地利 Orange Austria T-Mobile Austria A1 Telekom Austria AG (MobilKom) Azerbaijan 亞塞拜疆 Azercell Azerfon Bakcell Azores 亞速爾群島(葡) Vodafone Portugal TMN Bahamas 巴哈馬 BTC Bahrain 巴林 Batelco STC Bahrain (VIVA) zain BH (Vodafone Bahrain) Bangladesh 孟加拉 Robi (AKTel) Banglalink GrameenPhone Airtel (Warid Bangladesh) Barbados (West Indies) 巴巴多斯 (西印度群島) C&W (West Indies) Digicel Barbuda (West Indies) 巴布達 (西印度群島) C&W (West Indies) Digicel Belarus 白俄羅斯 MTS Belarus FE VELCOM (MDC) Belgium 比利時 Base NV/SA (KPN) MobiStar Belgacom Belize 伯利茲 BTL Benin 貝寧 Etisalat Benin S.A Spacetel Benin (MTN-Areeba) Bermuda 百慕達 Digicel Bhutan 不丹 B-Mobile Bhutan Bolivia 波利維亞 Entel Bornholm 波恩荷爾摩島 (丹) Telenor A/S Telia Danmark TDC A/S Bosnia and Herzegovina 波斯尼亞 HT Mobile Botswana 博茨瓦納 Orange Botswana Brazil 巴西 Brasil Telecom Celular (Oi Brazil) Claro Brasil TIM Brasil TNL PCS British Virgin -

Copy of Global and EU Data Plan Coverage

International Service Plan Coverage by Country 1/14/2010 EU Countries ‐ can use both Global and EU plans (SP‐303, SP‐304, SP‐305 and SP‐311) Country Network Austria Orange (ONE) Austria Mobilkom Austria T‐Mobile Austria Telering Belgium Base Belgium Belgacom Mobile (Proximus) Belgium Mobistar Bulgaria Cosmo Bulgaria Mobile EAD (Globul) Bulgaria MobilTel Cyprus Vodafone (CyTA) Cyprus MTN (Areeba, Scancom) Czech Republic Vodafone (Cesky) Czech Republic Telefónica O2 Czech Republic (EuroTel Praha) Czech Republic T‐Mobile Denmark TDC Mobil A/S (Vodafone) Denmark Sonofon Denmark Telia Danmark (TeliaSonera) Estonia EMT Finland TeliaSonera (Sonera) France, Monaco Orange France, Monaco SFR France, Monaco Bouygues Germany T‐Mobile Germany O2 Germany Vodafone Germany E Plus Greece Vodafone Greece Cosmote Greece Wind Hellas (STET Hellas ‐ TIM) Hungary Pannon Ireland Meteor Ireland Vodafone Ireland O2 Italy, Vatican Vodafone (Omnitel) Italy, Vatican WIND Italy, Vatican Telecom Italia (TIM) Latvia LMT Lithuania Omnitel Luxembourg P&T (LUX) Luxembourg Tango Malta Mobisle Comm. Ltd (GO) Malta Vodafone Netherlands Telfort Netherlands T‐Mobile Netherlands Vodafone Netherlands KPN Poland Polkomtel Poland Polska Telefonia Cyfrowa (ERA) Poland Orange (Centertel) Portugal Optimus Portugal TMN Portugal Vodafone Romania Orange Romania SA (Orange (MobilRom) Romania Vodafone Romania S.A.(MobiFon (Vodafone) Slovakia T‐Mobile (EuroTel) Slovakia Telefonica O2 Slovakia Slovenia SI.MOBIL Slovenia Mobitel Spain Vodafone Spain France Telecom Espana SA (Amena) Spain Telefonica -

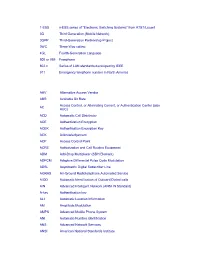

From AT&T/Lucent 3G Third Generation (Mobile Network) 3GPP

1-ESS x-ESS series of "Electronic Switching Systems" from AT&T/Lucent 3G Third Generation (Mobile Network) 3GPP Third-Generation Partnership Project 3WC Three Way calling 4GL Fourth-Generation Language 800 or 888 Freephone 802.x Series of LAN standards developed by IEEE 911 Emergency telephone number in North America AAV Alternative Access Vendor ABR Available Bit Rate Access Control, or Alternating Current, or Authentication Center (also AC AUC) ACD Automatic Call Distributor ACE Authentication Encryption ACEK Authentication Encryption Key ACK Acknowledgement ACP Access Control Point ACRE Authorization and Call Routing Equipment ADM Add-Drop Multiplexer (SDH Element) ADPCM Adaptive Differential Pulse Code Modulation ADSL Asymmetric Digital Subscriber Line AGRAS Air-Ground Radiotelephone Automated Service AIOD Automatic Identification of Outward Dialed calls AIN Advanced Intelligent Network (ANSI IN Standard) A-key Authentication key ALI Automatic Location Information AM Amplitude Modulation AMPS Advanced Mobile Phone System ANI Automatic Number Identification ANS Advanced Network Services ANSI American National Standards Institute ANSI-41 ANSI standard for mobile management (ANSI/TIA/EIA-41) ANT ADSL Network Terminator AOA Angle of Arrival AOL America On Line (ISP) API Application Programming Interface APPC Advanced Program-to Program Communications (IBM SNA) APPN Advanced Peer-to-Peer Network (IBM SNA) ARCnet Attached Resource Computer Network (Datapoint) ARDIS Advanced Radio Data Information Service ARP Address Resolution Protocol ARPA -

2020 Annual Report Dear Stockholders

2020 ANNUAL REPORT DEAR STOCKHOLDERS, 2020 was a year like no other for Consolidated Communications. Searchlight’s investment enabled us to completely refinance our debt and We entered the year with strong momentum and a clear set of strategic extend our maturity profile by seven years. Importantly, this investment goals to guide our path and focus for the year: and partnership with an experienced strategic investor in our sector is • stabilize revenue and EBITDA while growing free cash flow enabling us to accelerate our fiber expansion plans immediately. • leverage our network across the regional territories we serve while • We are in a strong position to accelerate our fiber investments with continuing to invest in the expansion of our fiber network; and a fully funded build, supporting our growth initiatives across three customer groups; carrier, commercial and consumer. We have • continue to execute on our disciplined capital allocation plan, including a embarked on a five-year investment initiative to upgrade 1.6 million strategic refinancing, to position the Company for investment in the future. passings and enable multi-gigabit, symmetrical speeds over fiber services. And then the COVID-19 pandemic arrived, testing us in previously We have a proven track record of growing broadband, and we are now unimaginable ways. But your Company and its employees responded positioned to expedite our fiber expansion plans, boost customer speeds with incredible energy, engagement and support for one another. We and expand gigabit fiber services to 70 percent of our addressable market. focused immediately and intensely to ensure the safety of our employees As part of our fiber expansion plans, we intend to transform the customer and customers while at the same time ensuring business continuity and experience by making it easy for customers to do business with us. -

The International Communications Market 2016

The International Communications Market 2016 4 4 TV and audio-visual 117 Contents 4.1 TV and audio-visual: overview and key market developments 119 Overview 119 Subscriptions to video-on-demand services continue to grow 121 4.2 The TV and audio-visual industry 125 Revenues 125 The licence fee and public funding 130 4.3 The TV and audio-visual consumer 132 Digital TV take-up 132 IPTV services and take-up 135 Value-added services 135 Broadcast television viewing 138 Legacy terrestrial channels viewing 139 Domestic publicly-owned channels viewing 140 118 4.1 TV and audio-visual: overview and key market developments Overview Subscription revenues continued to make up over half of total TV revenue Global TV revenues from broadcast advertising, channel subscription and public funding including licence fees reached £263bn in 2015. Subscription revenues continue to make up over half of total revenue, at £137bn. TV revenue per capita in the UK was £221 in 2015, the third highest of our comparator countries after Germany (£289) and the US (£351). South Korea had the highest take-up of pay TV at 99%, compared to the UK which had one of the lowest of our comparator countries at 62%. Just over half of UK television homes received an HD service in 2015 (51%), putting the UK in tenth position among our 18 comparator countries. Declines in viewing to broadcast TV occurred across many countries The UK experienced a year-on-year decline in viewing to broadcast TV (-1.9%), with people watching an average of 3 hours 36 minutes of TV each day. -

Advanced Info Services (AIS), 155 Advanced Wireless Research Initiative (AWRI), 35 Africa, 161-162 AIR 6468, 23 Alaskan Telco GC

Index Advanced Info Services (AIS), 155 Belgium Competition Authority Advanced Wireless Research Initiative (BCA), 73 (AWRI), 35 Bharti Airtel, 144, 162 Africa, 161–162 Bite,´ 88 AIR 6468, 23 Bouygues, 79 Alaskan telco GCI, 134 Brazil, 125 Altice USA, 132 Broadband Radio Services (BRS), America´ Movil,´ 125, 129 137–138 Android, 184 BT Plus, 105 Antel, 139 BT/EE, 185 Apple, 186–190 Bulgaria, 74 Asia Pacific Telecom (APT), 154 Asia-Pacific Telecommunity (APT), 6, C-band, 26 25–26 Cableco/MVNO CJ Hello, 153 AT&T, 129, 131 Canada, 125–127 Auction Carrier aggregation (CA), 5, 22 coverage obligation, 10 CAT Telecom, 155 plans, 137–139 Cellular IoT (CIoT), 31 reserve prices, 9 Centimetre wave (cmWave), 34–35 Auction methods, 8–9 Centuria, 88 combinatorial clock, 8 Ceragon Networks, 93 simultaneous multi-round Channel Islands Competition and ascending, 8 Regulatory Authorities Augmented reality, 195 (CICRA), 83, 88 Australia, 139–140 Chief Technology Officer (CTO), 185 Austria, 71–73 Chile, 127–128 Autonomous transport, 195 Chile, private networks, 127–128 Average revenue per user (ARPU), China, 141–142 165–166, 197 China Broadcasting Network (CBN), Axtel, 129 141 China Mobile, 141 Backhaul, 24–25 China Telecom, 141 Bahrain, 156 China Unicom, 39, 141–142 Batelco, 156 Chipsets, 186–190 Beamforming, 24, 29 Chunghwa Telecom, 154 Beauty contest, 8 Citizens Broadband Radio Service Belgacom, 73 (CBRS), 130–131 Belgium, 73–74 CK Hutchison, 145 210 Index Cloud computing, 24 Eir Group, 85 Co-operative MIMO. See Coordinated Electromagnetic fields (EMFs), 38–39 -

The Impact of Over the Top Service Providers on the Global Mobile Telecom Industry: a Quantified Analysis and Recommendations for Recovery

The impact of Over The Top service providers on the Global Mobile Telecom Industry: A quantified analysis and recommendations for recovery Ahmed Awwad Faculty of Science and Engineering, Anglia Ruskin University, Cambridge Campus, East Rd, Cambridge CB1 1PT, United Kingdom. [email protected] Key words: Mobile Network Operators (MNO), Over the top (OTT), Telecom industry revenue decrease, telecom operator’s revenue growth strategies. This work is licensed under Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) ABSTRACT Telecom industry is significantly evolving all over the analysis of global MNOs` revenue over the last globe than ever. Mobile users’ number is increasing decade. Additionally, the research aims to compile, remarkably. Telecom operators are investing to get evaluate, and analyse set of former proposed more users connected and to improve user strategies for MNOs to overcome the OTTs` impact. experience, however, they are facing various Methods –Referring to available open source raw challenges. Decrease of main revenue streams of data collected from GSMA and official voice calls, SMS (Short Message Service) and LDC telecommunications regulatory authorities (Long distance calls) with a significant increase in data worldwide, the research develops a statistical model traffic. In contrary, with free cost, OTT (Over the based on regression and extrapolation to analyse the top) providers such as WhatsApp and Facebook global MNOs` revenue trend. communication services rendered over networks that Findings – This study reveals a hidden revenue loss built and owned by MNOs. Recently, OTT services for global telecommunications industry represented gradually substituting the traditional MNOs` services in all MNOs all over the world. -

The Investment Gap for the Deployment of High-Speed Broadband in NUTS3 Regions

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Ferrandis, Jesús; Feijóo, Claudio; Ramos, Sergio Conference Paper The investment gap for the deployment of high- speed broadband in NUTS3 regions ITS Online Event, 14-17 June 2020 Provided in Cooperation with: International Telecommunications Society (ITS) Suggested Citation: Ferrandis, Jesús; Feijóo, Claudio; Ramos, Sergio (2020) : The investment gap for the deployment of high-speed broadband in NUTS3 regions, ITS Online Event, 14-17 June 2020, International Telecommunications Society (ITS), Calgary This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/224854 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von -

GDW-11 Westermo Teleindustri AB Teleindustri • Westermo 2007 ©

AT Commands Interface Guide 6615-2220 GDW-11 Westermo Teleindustri AB Teleindustri • Westermo 2007 © GDW-11 GSM/GPRS Modem GDW-11 485 GSM/GPRS Modem with RS-485 www.westermo.com Introduction This document describes the AT-commands that can be used to configure and control the GDW-1x modem. AT Commands Network message Network Responses The GDW-1x different operating modes are controlled by AT-commands. Modem operation modes: 1 Operating Online Mode Mode 2 3 5 4 Online Command Mode Example of commands/events that can trigger a change of the modems operation modes 1 – ATD command 2 – Hangup from the remote end 3 – Escape sequence +++ 4 – ATO command 5 – ATH command For more information about Westermo, please visit out website www.westermo.com 2 Introduction 6615-2220 Abbreviations and definitions Abbreviations ASCII American Standard Code for Information Interchange AT ATtention; this two-character abbreviation is always used to start a command line to be sent from TE to Modem BCD Binary Coded Decimal ETSI European Telecommunications Standards Institute IMEI International Mobile station Equipment Identity IRA International Reference Alphabet (ITU-T T.50 [13]) ISO International Standards Organisation ITU-T International Telecommunication Union – Telecommunications Standardization Sector ME Mobile Equipment, e.g. a GSM phone (equal to MS; Mobile Station) MOC / MTC A call from a GSM mobile station to the PSTN is called a “Mobile Originated Call” (MOC) or “outgoing call”, and a call from a fixed network to a GSM mobile station is called a “Mobile Terminated Call” (MTC) or “incoming call”. MoU Memorandum of Understanding (GSM operator joint) MS The words “Mobile Station” (MS) or “Mobile Equipment” (ME) are used for mobile terminals supporting GSM services. -

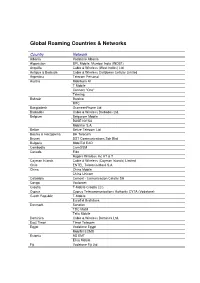

Global Roaming Countries & Networks

Global Roaming Countries & Networks Country Network Albania Vodafone Albania Afganistan BPL Mobile, Mumbai India (INDB1) Anguilla Cable & Wireless (West Indies) Ltd. Antigua & Barbuda Cable & Wireless Caribbean Cellular Limited Argentina Telecom Personal Austria Mobilkom A1 T-Mobile Connect "One" Telering Bahrain Batelco MTC Bangladesh GrameenPhone Ltd Barbados Cable & Wireless Barbados Ltd. Belgium Belgacom Mobile BASE NV/SA Mobistar S.A. Belize Belize Telecom Ltd Bosnia & Herzgovina BH Telecom Brunei DST Communications Sdn Bhd Bulgaria MobilTel EAD Cambodia CamGSM Canada Fido Rogers Wireless Inc AT & T Cayman Islands Cable & Wireless (Cayman Islands) Limited Chile ENTEL Telefonia Movil S.A China China Mobile China Unicom Colombia Comcel - Comunicacion Celular SA Congo Vodacom Croatia T-Mobile Croatia LLC Cyprus Cyprus Telecommunications Authority CYTA (Vodafone) Czech Republic T-Mobile EuroTel Bratislava Denmark Sonofon TDC Mobil Telia Mobile Dominica Cable & Wireless Dominica Ltd. East Timor Timor Telecom Egypt Vodafone Egypt MobiNil ECMS Estonia AS EMT Elisa Mobile Fiji Vodafone Fiji Ltd Country Network Finland Elisa Sonera Mobile Networks France Bouygues Telecom SFR Orange France French Polynesia (Tahiti) Tikiphone Georgia Geocell Ltd Germany T-Mobil Vodafone D2 GmbH E-Plus O2 - DEUE2 Greece Cosmote Vodafone Stet Hellas Telecommunications S.A. Grenada Cable & Wireless Grenada Ltd. Guernsey Cable & Wireless Guernsey Ltd Hong Kong Hutchison Telephone Co. Ltd Sunday / Mandarin Communications Ltd New World PCS Ltd China Resources Peoples