The Easy Way

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

State of California Department of Transportation Statement of Ongoing Contracts As of 01 District

State of California Department of Transportation Page 1 Statement of Ongoing Contracts as of 06/20/21 06/28/21 District 01 Location Awarded Contract Bid + CCOs Approved %Time Storm Water Resident Fed Aid Description Comp To date Est Comp % Work Plan Engineer Pgm Code Type Of Work Contractor This Month Accepted Message 01-DN-101-8.2/8.7 IN DEL NORTE COUNTY NEAR KLAMATH AT GOLDEN STATE BRIDGE, INC. CLAYTON MALMBERG $18,896,414 04/21/20 34% 01-0B0904 $5,157,126 05/08/20 PANTHER CREEK BRIDGE #01-0025 AND AT 3701 MALLARD DRIVE; 207 PROCE MALL 27% $1,310,631 08/05/22 HUNTER CREEK BRIDGE #01-0003 CRESCENT CITY, CA 95531 BENICIA CA 94510 REPLACE BRIDGE (707)496-5581 (925)372-8000 HA21 01-DN-101-12.5/15.5 IN DEL NORTE COUNTY NEAR KLAMATH FROM G R SUNDBERG, INC. SANDERS, KAREN $11,985,000 02/16/16 100% 01-0G1004 $11,984,109 05/04/16 0.4 MILE SOUTH OF WILSON CREEK BRIDGE 5211 BOYD ROAD 207 PRICE MALL 100% $0 04/09/21 TO 1.7 MILES NORTH OF RUDISIL ROAD CRESCENT CITY, CA 95531 ARCATA, CA 95521 DIR'S EMERGENCY F. (707)498-4009 OVER RUN (707)825-6565 ROADWAY STABILIZATION AND RETAINING 20.20 WALL R 201130 01-DN-101-25.5/27.4 IN DEL NORTE COUNTY IN AND NEAR S.T. RHOADES CONSTRUCTION, KAREN SANDERS $6,279,838 12/08/20 20% 01-0C6604 $1,447,194 12/29/20 CRESCENT CITY FROM 0.2 MILE SOUTH OF INC. -

Presidio of San Francisco an Outline of Its Evolution As a U.S

Special History Study Presidio of San Francisco An Outline of Its Evolution as a U.S. Army Post, 1847-1990 Presidio of San Francisco GOLDEN GATE National Recreation Area California NOV 1CM992 . Special History Study Presidio of San Francisco An Outline of Its Evolution as a U.S. Army Post, 1847-1990 August 1992 Erwin N. Thompson Sally B. Woodbridge Presidio of San Francisco GOLDEN GATE National Recreation Area California United States Department of the Interior National Park Service Denver Service Center "Significance, like beauty, is in the eye of the beholder" Brian W. Dippie Printed on Recycled Paper CONTENTS PREFACE vii ABBREVIATIONS viii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ix INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER 1: THE BEGINNINGS, 1846-1861 5 A. Takeover 5 B. The Indians 8 C. The Boundaries 9 D. Adobes, Forts, and Other Matters 10 CHAPTER 2: CIVIL WAR, 1861-1865 21 A. Organizing 21 B. Keeping the Peace 22 C. Building the Post 23 CHAPTER 3: THE PRESIDIO COMES OF AGE, 1866-1890 31 A. Peacetime 31 B. The Division Comes to the Presidio 36 C. Officers' Club, 20 46 D. Other Buildings 47 E. Troop Duty 49 F. Fort Winfield Scott 51 CHAPTER 4: BEAUTIFICATION, GROWTH, CAMPS, EARTHQUAKE, FORT WINFIELD SCOTT, 1883-1907 53 A. Beautification 53 B. Growth 64 C. Camps and Cantonments 70 D. Earthquake 75 E. Fort Winfield Scott, Again 78 CHAPTER 5: THE PRESIDIO AND THE FORT, 1906-1930 81 A. A Headquarters for the Division 81 B. Housing and Other Structures, 1907-1910 81 C. Infantry Terrace 84 D. Fires and Firemen 86 E. Barracks 35 and Cavalry Stables 90 F. -

Public Health Service Hospital Final Supplemental

Final Supplemental Environmental Impact Statement Public Health Service Hospital, The Presidio of San Francisco, CA This document provides new analysis, information, and changes made in response to public comments on the Draft Supplemental Environmental Impact Statement (SEIS) for the Public Health Service Hospital (PHSH), which was circulated and filed in August 2004. This document, together with the accompanying Response to Comments, will be filed as the Final SEIS. The Final SEIS is a supplement to and tiers from the 2002 Final EIS for the Presidio Trust Management Plan (PTMP), the Presidio Trust’s comprehensive land use plan and policy framework for Area B of the Presidio. The PTMP evaluated in the 2002 Final EIS included planning guidelines for the PHSH district. LEAD AGENCY The Presidio Trust (Trust), a federal corporation and executive agency created by Congress in 1996, is the lead agency for the proposed action under the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA). The Trust maintains jurisdiction over the interior 80 percent of the Presidio of San Francisco (Area B), while the National Park Service has jurisdiction over the coastal areas of the former army post (Area A). The Trust must preserve and enhance the Presidio and also become financially self-sufficient by the year 2013. ABSTRACT The Trust is proposing to rehabilitate and reuse buildings within the PHSH district of the Presidio, to re-introduce residential uses to the district, and to undertake related site improvements. These actions represent the “proposed action” evaluated in this Final SEIS. The Final SEIS evaluates five alternatives, including a publicly requested “no action” alternative and the PTMP baseline alternative. -

Exigency Report to the Board of Supervisors Re. SFPD's Joint

CITY AND COUNTY OF SAN FRANCISCO POLICE DEPARTMENT HEADQUARTERS 3 1245 R1 Street San Francisco, California 94158 LONDON N. BREED WILLIAM SCOTT MAYOR CHIEF OF POLICE August 5, 2021 Board of Supervisors City and County of San Francisco City Hall, Room 244 1 Dr. Canton B Goodlett P1 San Francisco, CA 94102 President Walton and Members: Re: S.F. Administrative Code 1913.7, Exigency Report: Joint Search Operation and Unmanned Aerial Support (UAS/Drone) Involvement on June 7, 2021 Chapter 19B of the San Francisco Administrative Code ("Chapter 19B") was enacted in August 2019. Under Section 19B.7, the San Francisco Police Department ("SFPD" or "Department") is required to report to the Board of Supervisors the acquisition or use of Surveillance Technology, as defined by Chapter 19B, in exigent circumstances. On June 7, 2021, the Department participated in a multi-agency search for a missing 84-year-old person where the Mann County Sheriff's Office's Small Unmanned Aerial System Team used and operated an Unmanned Aerial System (UAS), commonly known as a drone. At no time did SFPD members operate or use the UAS directly, nor did SFPD members acquire the UAS. But SFPD members aiding with the terrain search benefitted from observations and information provided by Mann County Sheriffs Deputies operating the UAS. As the Department partnered with the Mann County Sherriff's Department's use of its Surveillance Technology, as defined by Chapter 19B, the Department issues this 19B.7 Exigency Report to the Board of Supervisors. As required, this exigency -

Tunnel Road Safety: a Look at Older Drivers’ Performance

TUNNEL ROAD SAFETY: A LOOK AT OLDER DRIVERS’ PERFORMANCE AND SIGHT IMPAIRMENT A Thesis presented to the Faculty of California Polytechnic State University, San Luis Obispo In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degrees Master of City & Regional Planning Master of Science in Engineering (Transportation Planning Specialization) by Edith Lopez Victoria March 2014 © 2014 Edith Lopez Victoria ALL RIGHTS RESERVED Page ii COMMITTEE MEMBERSHIP TITLE: Tunnel Road Safety: A Look at Older Drivers’ Performance and Sight Impairment AUTHOR: Edith Lopez Victoria DATE SUBMITTED: March 2014 COMMITTEE CHAIR: Dr. Cornelius Nuworsoo, Associate Professor City & Regional Planning Department COMMITTEE MEMBER: Dr. Anurag Pande Assistant Professor Civil Engineering Department COMMITTEE MEMBER: Chris Clark, JD, Lecturer City & Regional Planning Department Page iii ABSTRACT Tunnel Road Safety: A Look at Older Drivers’ Performance and Sight Impairment Edith Lopez Victoria In California, there is an observed trend in which collisions cluster in and around tunnels. The break in road continuity created by the tunnels disturbs traffic flow that can lead to collisions. One of the main contrasts between open roads and tunnel roads occurs in lighting. Drivers with sight deficiencies are unable to adapt their sight to the change in the lighting environment and may crash due to misperception of road alignment, vehicle’s speed and other physiological reactions, such as tension. The suspect population group of crashes occurring under the influence of tunnels conditions is older drivers. The literature suggests that sight and driving performance deteriorate with age. This research attempted to validate this claim by performing a study that looked at driver and crash characteristic of injury and fatal collisions that occurred in and around tunnels. -

Measurements Alt a Alt B Alt C Alt D Alt E Preferred Trails

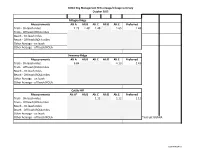

GOGA Dog Management SEIS acreage/mileage summary October 2012 Milagra Ridge Measurements Alt A Alt B Alt C Alt D Alt E Preferred Trails - On leash miles 2.73 1.48 1.48 1.65 1.48 Trails - Off leash/ROLA miles Beach - On leash miles Beach - Off leash/ROLA miles Other Acreage - on leash Other Acreage - off leash/ROLA Sweeney Ridge Measurements Alt A Alt B Alt C Alt D Alt E Preferred Trails - On leash miles 6.84 4.13 2.43 Trails - Off leash/ROLA miles Beach - On leash miles Beach - Off leash/ROLA miles Other Acreage - on leash Other Acreage - off leash/ROLA Cattle Hill Measurements Alt A* Alt B Alt C Alt D Alt E Preferred Trails - On leash miles 1.12 1.12 1.12 Trails - Off leash/ROLA miles Beach - On leash miles Beach - Off leash/ROLA miles Other Acreage - on leash Other Acreage - off leash/ROLA *not yet GGNRA GGNRA004235 GOGA Dog Management SEIS acreage/mileage summary October 2012 Pedro Point Measurements Alt A* Alt B Alt C Alt D Alt E Preferred Trails - On leash miles 0.31 0.31 2.40 0.31 Trails - Off leash/ROLA miles Beach - On leash miles Beach - Off leash/ROLA miles Other Acreage - on leash Other Acreage - off leash/ROLA *not yet GGNRA Rancho Corral de Tierra Measurements Alt A Alt B Alt C Alt D Alt E Preferred Trails - On leash miles 16.2* 6.48 6.48 1.10 6.48 6.48 Alt A mileage for info only Trails - Off leash/ROLA miles Note: alts B, C, D, E updated Beach - On leash miles trail milage to reflect alt maps Beach - Off leash/ROLA miles Other Acreage - on leash 3858.00 Other Acreage - off leash/ROLA 1.39 1.39 GGNRA004236 Golden Gate National -

2020 Named Freeway Publication

Photograph taken by Caltrans Photography 2020 Named Freeways, Highways, Structures and Other Appurtenances in California Prepared by The California Department of Transportation © 2021 California Department of Transportation. All Rights Reserved. [page left intentionally blank] 2020 Named Freeways, Highways, Structures and Other Appurtenances in California STATE OF CALIFORNIA Gavin Newsom, Governor CALIFORNIA STATE TRANSPORTATION AGENCY David S. Kim, Secretary CALIFORNIA DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION Toks Omishakin, Director CALTRANS DIVISION OF RESEARCH, INNOVATION and SYSTEM INFORMATION Office of Highway System Information and Performance January 2021 [page left intentionally blank] PREFACE 2020 Named Freeways, Highways, Structures and Other Appurtenances in California Named Freeways, Highways, Structures and Other Appurtenances in California is produced by the California Department of Transportation (Caltrans) as a reference on the many named facilities that are a part of the California State Highway System. This publication provides information on officially named freeways; highways; structures such as bridges, tunnels, and interchanges; Blue Star Memorial Highways; Safety Roadside Rest Areas; and memorial plaques. A section concerning historical names is also included in this publication. The final section of this publication includes background information on each naming. HOW FREEWAYS, HIGHWAYS AND STRUCTURES ARE NAMED Each route in the State Highway System is given a unique number for identification and signed with distinctive numbered Interstate, United States, or California State route shields to guide public travel. The State Legislature designates all State highway routes and assigns route numbers, while the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials (AASHTO) has authority over the numbering of Interstate and United States routes. In addition to having a route number, a route may also have a name and, in some cases, multiple names. -

Public Health Service Hospital Final Supplemental

Contents APPENDICES A FINANCIAL ANALYSIS OF PHSH ALTERNATIVES B TRANSPORTATION TECHNICAL MEMORANDA Technical Memorandum 1 – Expanded Existing Conditions Technical Memorandum 2 – Expanded Travel Demand Assumptions Technical Memorandum 3 – Expanded Transportation Impact Analysis of Alternatives Technical Memorandum 4 – Existing Year (2005) + Project Transportation Impact Analysis of Alternatives Technical Memorandum 5 – Sensitivity Analysis for Trip Generation and Assignment Technical Memorandum 6 – Alternative 1 Trip Generation Variation Technical Memorandum 7 – Traffic Signal Warrant Analysis C ENVIRONMENTAL REVIEW SUMMARY Public Health Service Hospital Final SEIS Appendices i Appendix A Financial Analysis of PHSH Alternatives APPENDIX A FINANCIAL ANALYSIS OF PHSH EIS ALTERNATIVES PHSH DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMS MAY 2006 Requested No Action Alternative 1 Alternative 2 Alternative 3 Alternative 4 Project Description Gross Building Area Residential 0 0% 209,200 52% 337,100 84% 233,000 85% 332,000 92% Non-Residential 68,000 100% 190,800 48% 62,900 16% 42,000 15% 30,000 8% Total 68,000 100% 400,000 100% 400,000 100% 275,000 100% 362,000 100% Unit Count Market Rate 0 210 230 230 114 Senior Housing 0 0 0 0 155 Total Units 0 210 230 230 269 Unit Mixed Studio N.A. 52 6 88 21 1 Bedroom N.A. 146 103 130 146 2 Bedrooms N.A. 1 105 1 88 3 Bedrooms/ Wyman N.A. 11 16 11 14 Unit Size Studio N.A. 380 460 517 500 1 Bedroom N.A. 700 747 700 700 2 Bedrooms N.A. 1,100 1,241 1,100 1,100 3 Bedrooms/ Wyman N.A. 2,100 1,609 2,100 1,650 Weighted Average N.A. -

With Audited Financial Statements

A Park Emerges THE PRESIDIO TRUST 2003 YEAR-END REPORT Table of Contents 1 Mission Statement 2 Message from the Chairman 4 Message from the Executive Director 6 Historical Overview 8 About the Trust 10 Restoring the Park 18 Supporting the Park 22 Enjoying the Park 26 Awards and Honors 27 Financial Statements 57 Board of Directors 58 Organizations at the Presidio 59 Points of Interest THE PRESIDIO TRUST 2003 YEAR-END REPORT The Presidio Trust’s mission is to preserve and enhance the natural, cultural, scenic, and recreational resources of the Presidio for public use in perpetuity, and to achieve long- term financial sustainability. These efforts encompass the natural areas, wildlife, and native habitats of the park, as well as the historic structures and designed landscapes that make the park a National Historic Landmark District. The Presidio Trust is dedicated to ensuring that visitors to this spectacular place will have the opportunity to gain a broader understanding of the Presidio and its place in American History. A PARK EMERGES 1 Message from the Chairman Congress preserved the Presidio by making explicit the cost programs. The tax credit provides an economic incentive for private investment in historic of its public benefits. This continues to stir public debate, buildings which might otherwise be financially because the Presidio is unlike any other national park. There infeasible to rehabilitate and reuse. The most ambitious example of historic tax is no precedent or template for what we are trying to do here. credit at work in the Presidio is the Public Health Service Hospital complex, the largest historic In creating the Presidio Trust, Congress linked end of FY 2003, 774 non-historic and 167 historic preservation effort we have yet undertaken (see the Presidio’s preservation to its economics. -

Annual Listing of Federally Obligated Projects

Annual Listing of Federally Obligated Projects Federal Fiscal Year 2020 (October 1, 2019– September 30, 2020) (Cover photos: (top left) Antioch: Pavement Rehabilitation Project; (top right) Bay Area Rapid Transit District: Railcar Procurement Program; (bottom) Golden Gate Bridge, Highway, and Transportation District: Golden Gate Bridge Suicide Deterrent System) December 29, 2020 TO: Federal Highway Administration, Federal Transit Administration, Caltrans, Interested Agencies, Organizations and Individuals RE: Annual Listing of Federally Obligated Projects for Federal Fiscal Year 2019-20 The Metropolitan Transportation Commission, as the Metropolitan Planning Organization (MPO) for the nine county San Francisco Bay Area, is required to publish a listing of projects using federal funds obligated in the previous federal fiscal year (Title 23 CFR 450.334). The Annual Listing of Federally Obligated Projects (“Annual Listing”) provides a record of project delivery and promotes awareness of federal spending on transportation projects. The Annual Listing includes explanatory text, as well as summary listings by categories such as mode, system, and fund source. Additionally, the Annual Listing includes a glossary of the commonly used abbreviations and acronyms to help the public better understand the listing. The Fixing America’s Surface Transportation (FAST) Act also encourages cooperation among the state department of transportation (Caltrans), public transit operators, and MTC to develop this Annual Listing. As a part of our development process, MTC distributed the draft Annual Listing to the Bay Area Partnership Working Groups and stakeholders for review and comment. This report was developed using data sourced from both Caltrans and MTC. For the last federal fiscal year (October 1, 2019 through September 30, 2020), the region obligated approximately $2.2 billion in federal transportation funds. -

San Francisco Tunnels — Past, Present and Future 14 Take a Tour of the Busy Underground of NAT 2008’S Host City

Reader Service Number 1 CONTENTS June CONTENTS2008 Cover Story San Francisco Tunnels — Past, Present and Future 14 Take a tour of the busy underground of NAT 2008’s host city... By Victor S. Romero Napa Valley Wine Caves 18 ...and cap off your stay with a visit to the wine country with a look at wine cave construction. By Jan Van Greunen Features On the Waterfront 20 Beach sewer tunnel emergency repair and rehabilitation project 20 requires boat access to the work site. By Albert Ruiz, David Jurich and Joseph McDivitt 3-D Scanning in Tunneling 25 Fast, accurate measurement is a difficult aspect in tunnel construc- tion, maintenance and redevelopment. By John Stenmark Contractor Claims Against the Owner’s Designer 30 Can a contractor sue an engineer or other design professional directly for misrepresentations in the plans and specifications? By Peter Kutil and Karl Silverberg North American Tunnel Project Update 34 By Jack Burke 25 Columns Editor’s Message . 4 Departments Business Briefs . 6 Global . 12 TBM: Tunnel Business Magazine (ISSN 1553-2917) is published six times per year. Copyright 2008, Benjamin Media Inc., P.O. Box 190, Peninsula, OH 44264. USA All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or trans- Calendar. 40 mitted by any means without written permission from the publisher. One year subscription rates: complimentary in the United States and Canada, and $69 in Products . 41 other foreign countries. Single copy rate: $10. Subscriptions and classified adver- tising should be addressed to the Peninsula office. Postmaster return form 1579 to TBM: Tunnel Business Magazine, P.O. -

NPR Tomorrow Radio(Sm) Field Test Report

National Public Radio Washington, D.C. Tomorrow RadioSM Field Testing in the Washington, D.C., New York City San Francisco, and Los Angeles (Long Beach) Radio Markets Project Sponsors: National Public Radio Kenwood Corporation Harris Corporation January 6, 2004 ©2004 All rights reserved. National Public Radio • Washington, D.C. 2003 Field Testing of Tomorrow RadioSM FM HD Radio Enhancement Executive Summary The National Public Radio (NPR) Tomorrow RadioSM field testing project was conceived to evaluate mobile reception performance of a modification to the In-Band On-Channel (IBOC) digital FM system presently authorized by the FCC. The Tomorrow RadioSM concept extends IBOC digital radio by splitting the single digital program channel into two digital program channels. The purpose of the field testing project has been to evaluate “real world” mobile reception coverage of the Tomorrow RadioSM channel portion of the system to determine if it exhibits robustness sufficient to support a stand-alone second program service, capable of being delivered to a wide audience within the normal analog service area of the host FM station. Field test data gathering of the Tomorrow RadioSM enhancement has taken place over the summer and autumn of 2003 in four separate radio markets, Washington, D.C., New York City, San Francisco, and Los Angeles/Long Beach. Testing has been sponsored by project partners NPR, Harris Corporation, and Kenwood Corporation, with added project support by iBiquity Digital Corporation. Testing took place in two phases. The original testing phase took place in all four markets over August and September 2003, while a regression testing phase took place in the Washington, D.C.