Searching for Wilson's Expedition to Australia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

7008 Australian Native Plants Society Australia Hakea

FEBRUARY 20 10 ISSN0727 - 7008 AUSTRALIAN NATIVE PLANTS SOCIETY AUSTRALIA HAKEA STUDY GROUP NEWSLETTER NUMBER 42 Leader: Paul Kennedy PO Box 220 Strathmerton,Vic. 3 64 1 e mail: hakeaholic@,mpt.net.au Dear members. The last week of February is drawing to a close here at Strathrnerton and for once the summer season has been wetter and not so hot. We have had one very hot spell where the temperature reached the low forties in January but otherwise the maximum daily temperature has been around 35 degrees C. The good news is that we had 25mm of rain on new years day and a further 60mm early in February which has transformed the dry native grasses into a sea of green. The native plants have responded to the moisture by shedding that appearance of drooping lack lustre leaves to one of bright shiny leaves and even new growth in some cases. Many inland parts of Queensland and NSW have received flooding rains and hopefully this is the signal that the long drought is finally coming to an end. To see the Darling River in flood and the billabongs full of water will enable regeneration of plants, and enable birds and fish to multiply. Unfortunately the upper reaches of the Murray and Murrurnbidgee river systems have missed out on these flooding rains. Cliff Wallis from Merimbula has sent me an updated report on the progress of his Hakea collection and was complaining about the dry conditions. Recently they had about 250mm over a couple of days, so I hope the species from dryer areas are not sitting in waterlogged soil. -

ENNZ: Environment and Nature in New Zealand

ISSN: 1175-4222 ENNZ: Environment and Nature in New Zealand Volume 4, Number 1, April 2009 ii ABOUT Us ENNZ provides a forum for debate on environmental topics through the acceptance of peer reviewed and non peer reviewed articles, as well as book and exhibition reviews and postings on upcoming events, including conferences and seminars. CONTACT If you wish to contribute articles or reviews of exhibitions or books, please contact: Dr. James Beattie Department of History University of Waikato Private Bag 3105 Hamilton 3240 Ph: 07 838 4466 Ext 6459 [email protected] CHIEF EDITOR Dr. James Beattie ASSOCIATE EDITORS Dr. Charles Dawson Dr. Julian Kuzma Dr. Matt Morris Ondine Godtschalk ENNZ WEBSITE http://fennerschool- associated.anu.edu.au/environhist/newzealand/newsletter/ iii THANKS Thanks to Dr Libby Robin and Cameron Muir, both of the Australian National University, to the Fenner School of Environment and Society for hosting this site and to Mike Bell, University of Waikato, for redesigning ENNZ. ISSN: 1175-4222 iv Contents i-iv TITLE & PUBLICATION DETAILS V EDITORIAL INTRODUCTION 1 – 13 ARTICLE: PAUL STAR, ‘ENVIRONMENTAL HISTORY AND NEW ZEALAND HISTORY’ 14-36 ARTICLE: MATT HENRY, ‘TRANS-TASMAN METEOROLOGY AND THE PRODUCTION OF A TASMAN AIRSPACE, 1920-1940’ 37-57 ARTICLE: JAMES BEATTIE, ‘EXPLORING TRANS-TASMAN ENVIRONMENTAL CONNECTIONS, 1850S-1900S, THROUGH THE IMPERIAL CAREERING OF ALFRED SHARPE’ 58-77 ARTICLE: MIKE ROCHE, ‘LATTER DAY ‘IMPERIAL CAREERING’: L.M. ELLIS – A CANADIAN FORESTER IN AUSTRALIA AND NEW ZEALAND, 1920-1941’ 78-82 REVIEW: PAUL STAR ON KIRSTIE ROSS’ GOING BUSH: NEW ZEALANDERS AND NATURE IN THE TWENTIETH CENTURY v ‘EDITORIAL INTRODUCTION’ JAMES BEATTIE Welcome to the first issue of 2009. -

Hedges 3 Busselton and Surrounds Greater Wa, and Greater Australia

HEDGES 3 BUSSELTON AND SURROUNDS GREATER WA, AND GREATER AUSTRALIA Selection of plant species and notes on hedges - Richard Clark This list of hedge plant species includes Western Australian species and species from Greater Australia. Scientific Name Common Name Acacia cochlearis Rigid Wattle Acacia cyclops Coastal Wattle Acacia lasiocarpa Dune Moses, Panjang Acacia saligna Golden Wreath Wattle Acacia urophylla Tail-leaved Acacia Adenanthos cygnorun Common Woollybush Adenanthos sericeus Woollybush Adenanthos x cunninghamii Albany Woollybush Adriana quadripartita Coast Bitterbush Agonis flexuosa nana Allocasuarina humilis Scrub Sheoak Allocasuarina thuyoides Horned Sheoak Alyogyne hakeifolia Red-centred hibiscus Alyogyne huegelii Lilac Hibiscus Alyogyne pinoniana Sand Hibiscus Alyxia buxifolia Sea Box Atriplex cinerea Grey Saltbush Atriplex isatidea Coast Saltbush Atriplex nummularia Oldman Saltbush Banksia sessilis Parrot Bush Beaufortia squarrosa Sand Bottlebrush Beyeria viscosa Pinkwood Billardiera fusiformis Australian Bluebell Bossiaea aquifolium Water Bush Bossiaea disticha Bossiaea linophylla Golden Cascade Callistachys lanceolata Native Willow (Wonnich) Calytrix acutifolia Calytrix tetragona Common Fringe-myrtle Scientific Name Common Name Chamelaucium axillare (NOT LOCAL - WA) Esperence Wax Flower Chamelaucium floriferum subsp. diffusum Walpole Wax Chamelaucium uncinatum Geraldton Wax Chamelaucium x Verticordia 'Eric John' Chamelaucium x Verticordia 'Paddy's Pink' Correa alba White Correa Diplolaena dampieri Southern Diplolaena -

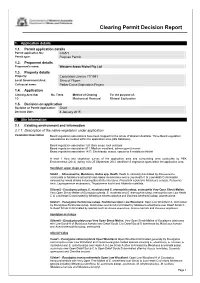

Clearing Permit Decision Report

Clearing Permit Decision Report 1. Application details 1.1. Permit application details Permit application No.: 6365/1 Permit type: Purpose Permit 1.2. Proponent details Proponent’s name: Western Areas Nickel Pty Ltd 1.3. Property details Property: Exploration Licence 77/1581 Local Government Area: Shire of Yilgarn Colloquial name: Parker Dome Exploration Project 1.4. Application Clearing Area (ha) No. Trees Method of Clearing For the purpose of: 10 Mechanical Removal Mineral Exploration 1.5. Decision on application Decision on Permit Application: Grant Decision Date: 8 January 2015 2. Site Information 2.1. Existing environment and information 2.1.1. Description of the native vegetation under application Vegetation Description Beard vegetation associations have been mapped for the whole of Western Australia. Three Beard vegetation associations are located within the application area (GIS Database): Beard vegetation association 128: Bare areas; rock outcrops Beard vegetation association 511: Medium woodland; salmon gum & morrel Beard vegetation association 1413: Shrublands; acacia, casuarina & melaleuca thicket A level 1 flora and vegetation survey of the application area and surrounding area conducted by PEK Environmental (2014) during 14 to 25 September 2012 identified 15 vegetation types within the application area: Sandplain upper slope and crest SUah1 - Allocasuarina, Melaleuca, Hakea spp. Heath. Heath A, variously dominated by Allocasuarina corniculata or Melaleuca atroviridis and Hakea meisneriana over a Low Heath C to Low Heath D dominated variously by mixed shrubs including Beaufortia interstans , Phebalium lepidotum , Melaleuca cordata , Persoonia helix , Leptospermum erubescens , Thryptomene kochii and Hibbertia rostellata . SUesm2 - Eucalyptus pileata , E. moderata and E. eremophila subsp. eremophila Very Open Shrub Mallee. -

For Perspectives in Plant Ecology, Evolution and Systematics Manuscript Draft

Elsevier Editorial System(tm) for Perspectives in Plant Ecology, Evolution and Systematics Manuscript Draft Manuscript Number: PPEES-D-15-00109R1 Title: Bird pollinators, seed storage and cockatoo granivores explain large woody fruits as best seed defense in Hakea Article Type: Research paper Section/Category: Keywords: Black cockatoo; Crypsis; Fruit and seed size; Granivory; Resprouter; Spinescence Corresponding Author: Prof. Byron Lamont, Corresponding Author's Institution: Curtin University First Author: Byron Lamont Order of Authors: Byron Lamont; Byron Lamont; Mick Hanley; Philip Groom Abstract: Nutrient-impoverished soils with severe summer drought and frequent fire typify many Mediterranean-type regions of the world. Such conditions limit seed production and restrict opportunities for seedling recruitment making protection from granivores paramount. Our focus was on Hakea, a genus of shrubs widespread in southwestern Australia, whose nutritious seeds are targeted by strong-billed cockatoos. We assessed 56 Hakea species for cockatoo damage in 150 populations spread over 900 km in relation to traits expected to deter avian granivory: dense spiny foliage; large, woody fruits; fruit crypsis via leaf mimicry and shielding; low seed stores; and fruit clustering. We tested hypothesises centred on optimal seed defenses in relation to to a) pollination syndrome (bird vs insect), b) fire regeneration strategy (killed vs resprouting) and c) on-plant seed storage (transient vs prolonged). Twenty species in 50 populations showed substantial seed loss from cockatoo granivory. No subregional trends in granivore damage or protective traits were detected, though species in drier, hotter areas were spinier. Species lacking spiny foliage around the fruits (usually bird-pollinated) had much larger (4−5 times) fruits than those with spiny leaves and cryptic fruits (insect-pollinated). -

Earle Page and the Imagining of Australia

‘NOW IS THE PSYCHOLOGICAL MOMENT’ EARLE PAGE AND THE IMAGINING OF AUSTRALIA ‘NOW IS THE PSYCHOLOGICAL MOMENT’ EARLE PAGE AND THE IMAGINING OF AUSTRALIA STEPHEN WILKS Ah, but a man’s reach should exceed his grasp, Or what’s a heaven for? Robert Browning, ‘Andrea del Sarto’ The man who makes no mistakes does not usually make anything. Edward John Phelps Earle Page as seen by L.F. Reynolds in Table Talk, 21 October 1926. Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] Available to download for free at press.anu.edu.au ISBN (print): 9781760463670 ISBN (online): 9781760463687 WorldCat (print): 1198529303 WorldCat (online): 1198529152 DOI: 10.22459/NPM.2020 This title is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). The full licence terms are available at creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode This publication was awarded a College of Arts and Social Sciences PhD Publication Prize in 2018. The prize contributes to the cost of professional copyediting. Cover design and layout by ANU Press. Cover photograph: Earle Page strikes a pose in early Canberra. Mildenhall Collection, NAA, A3560, 6053, undated. This edition © 2020 ANU Press CONTENTS Illustrations . ix Acknowledgements . xi Abbreviations . xiii Prologue: ‘How Many Germans Did You Kill, Doc?’ . xv Introduction: ‘A Dreamer of Dreams’ . 1 1 . Family, Community and Methodism: The Forging of Page’s World View . .. 17 2 . ‘We Were Determined to Use Our Opportunities to the Full’: Page’s Rise to National Prominence . -

The Vegetation of the Ravensthorpe Range, Western Australia

The vegetation of the Ravensthorpe Range, Western Australia: I. Mt Short to South Coast Highway G.F. Craig E.M. Sandiford E.J. Hickman A.M. Rick J. Newell The vegetation of the Ravensthorpe Range, Western Australia: I. Mt Short to South Coast Highway December 2007 by G.F. Craig E.M. Sandiford E.J. Hickman A.M. Rick J. Newell © Copyright. This report and vegetation map have been prepared for South Coast Natural Resource Management Inc and the Department of Environment and Conservation (DEC Albany). They may not be reproduced in part or whole by electronic, mechanical or other means, including photocopying, recording or any information storage system, without the express approval of South Coast NRM, DEC Albany or an author. In undertaking this work, the authors have made every effort to ensure the accuracy of the information used. Any conclusions drawn or recommendations made in the report and map are done in good faith and the consultants take no responsibility for how this information is used subsequently by others. Please note that the contents in this report and vegetation map may not be directly applicable towards another organisation’s needs. The authors accept no liability whatsoever for a third party’s use of, or reliance upon, this specific report and vegetation map. Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS.................................................................................................................................................. I SUMMARY ................................................................................................................................................................... -

Australian Native Plants Society Australia Hakea

AUSTRALIAN NATIVE PLANTS SOCIETY AUSTRALIA HAKEA STUDY GROUP NEWSLETTER No. 61 JUNE 2016 ISSN0727-7008 Leader: Paul Kennedy 210 Aireys St. Elliminyt 3250 E mail [email protected] Tel. 03-52315569 Dear members. How quickly the year is passing. The long dry summer has finally given way to milder autumn days and wet weather. In the first two weeks of May we have received 80mm of rain, which is more than all the rain we have had in the previous four months. I watered the smaller Hakeas sparingly over the dry period and now that the rains have come they should be able to survive on their own. Our garden. It has been rather hectic around here. The builders finally arrived to build a patio and pergola in the front of the house. At the same time construction of a proper driveway and brick paved paths to various parts of the garden commenced. I have already moved approximately 100 barrow loads of sandy loam soil to other parts of the garden to form more raised beds and there are still a lot more to move yet. I am confident the final landscape will look good. Keeping builders away from standing on plants is always difficult. Even roping off areas where special plants exist does not ensure that they will not find a reason to erect a ladder in that spot. Our Hakea collection now stands at 145 species in the ground. Travels. Just before Easter Barbara and I set off for a trip through the eastern Victorian Alps and along the border to Bonang, then crossing into NSW to Bombala, Jindabyne, Canberra and Milton. -

Norrie's Plant Descriptions - Index of Common Names a Key to Finding Plants by Their Common Names (Note: Not All Plants in This Document Have Common Names Listed)

UC Santa Cruz Arboretum & Botanic Garden Plant Descriptions A little help in finding what you’re looking for - basic information on some of the plants offered for sale in our nursery This guide contains descriptions of some of plants that have been offered for sale at the UC Santa Cruz Arboretum & Botanic Garden. This is an evolving document and may contain errors or omissions. New plants are added to inventory frequently. Many of those are not (yet) included in this collection. Please contact the Arboretum office with any questions or suggestions: [email protected] Contents copyright © 2019, 2020 UC Santa Cruz Arboretum & Botanic Gardens printed 27 February 2020 Norrie's Plant Descriptions - Index of common names A key to finding plants by their common names (Note: not all plants in this document have common names listed) Angel’s Trumpet Brown Boronia Brugmansia sp. Boronia megastigma Aster Boronia megastigma - Dark Maroon Flower Symphyotrichum chilense 'Purple Haze' Bull Banksia Australian Fuchsia Banksia grandis Correa reflexa Banksia grandis - compact coastal form Ball, everlasting, sago flower Bush Anemone Ozothamnus diosmifolius Carpenteria californica Ozothamnus diosmifolius - white flowers Carpenteria californica 'Elizabeth' Barrier Range Wattle California aster Acacia beckleri Corethrogyne filaginifolia - prostrate Bat Faced Cuphea California Fuchsia Cuphea llavea Epilobium 'Hummingbird Suite' Beach Strawberry Epilobium canum 'Silver Select' Fragaria chiloensis 'Aulon' California Pipe Vine Beard Tongue Aristolochia californica Penstemon 'Hidalgo' Cat Thyme Bird’s Nest Banksia Teucrium marum Banksia baxteri Catchfly Black Coral Pea Silene laciniata Kennedia nigricans Catmint Black Sage Nepeta × faassenii 'Blue Wonder' Salvia mellifera 'Terra Seca' Nepeta × faassenii 'Six Hills Giant' Black Sage Chilean Guava Salvia mellifera Ugni molinae Salvia mellifera 'Steve's' Chinquapin Blue Fanflower Chrysolepis chrysophylla var. -

The Following Is the Initial Vaughan's Australian Plants Retail Grafted Plant

The following is the initial Vaughan’s Australian Plants retail grafted plant list for 2019. Some of the varieties are available in small numbers. Some species will be available over the next few weeks. INCLUDING SOME BANKSIA SP. There are also plants not listed which will be added to a future list. All plants are available in 140mm pots, with some sp in 175mm. Prices quoted are for 140mm pots. We do not sell tubestock. Plants placed on hold, (max 1month holding period) must be paid for in full. Call Phillip Vaughan for any further information on 0412632767 Or via e-mail [email protected] Grafted Grevilleas $25.00ea • Grevillea Albiflora • Grevillea Alpina goldfields Pink • Grevillea Alpina goldfields Red • Grevillea Alpina Grampians • Grevillea Alpina Euroa • Grevillea Aspera • Grevillea Asparagoides • Grevillea Asparagoides X Treueriana (flaming beauty) • Grevillea Baxteri Yellow (available soon) 1 • Grevillea Baxteri Orange • Grevillea Beadleana • Grevillea Biformis cymbiformis • Grevillea Billy bonkers • Grevillea Bipinnatifida "boystown" • Grevillea Bipinnatifida "boystown" (prostrate red new growth) • Grevilllea Bipinnatifida deep burgundy fls • Grevillea Bracteosa • Grevillea Bronwenae • Grevillea Beardiana orange • Grevillea Bush Lemons • Grevillea Bulli Beauty • Grevillea Calliantha • Grevillea Candelaborides • Grevillea Candicans • Grevillea Cagiana orange • Grevillea Cagiana red • Grevillea Crowleyae • Grevillea Droopy drawers • Grevillea Didymobotrya ssp involuta • Grevillea Didymobotrya ssp didymobotrya • Grevillea -

List of Native Plants Grown in the Melville–Cockburn Area Compiled

List of native plants grown in the Melville–Cockburn area compiled by the Murdoch Branch of the Wildflower Society of Western Australia The plants listed here have been grown in the suburb indicated or at Murdoch University for at least seven years and are considered reliable. Plant size is a guide. For some species there are now selections or cultivars that may grow taller or shorter. An asterisk * indicates not native to Western Australia. Suburb abbreviations: H Hilton, K Kardinya, NL North Lake, W Winthrop MU Murdoch University TREES (7 metres and taller) Acacia acuminata Jam K Acacia aneura Mulga K Acacia aptaneura Slender Mulga K Acacia ayersiana Broad-leaf Mulga K Acacia denticulosa Sandpaper Wattle K Acacia lasiocalyx K *Acacia podalyriaefolia Queensland Silver Wattle K Acacia saligna Black Wattle K Acacia steedmanii W Actinostrobus arenarius Sandplain Cypress K Agonis flexuosa WA Peppermint H, K, MU Allocasuarina fraseriana Sheoak H, K Banksia ashbyi subsp. ashbyi K, MU Banksia attenuata Slender Banksia K, MU, W Banksia grandis Bull Banksia K, MU, W *Banksia integrifolia subsp. integrifolia Coast Banksia H, MU Banksia menziesii Menzies Banksia MU, W Banksia prionotes Acorn Banksia MU *Brachychiton discolor Lacebark Kurrajong H Callitris preissii Rottnest Cypress K Corymbia calophylla Marri K Eucalyptus caesia subsp. caesia Caesia K, MU Eucalyptus caesia subsp. magna Silver Princess MU *Eucalyptus citriodora Lemon-scented Gum K Eucalyptus diversicolor Karri K Eucalyptus erythrocorys Illyarrie K, MU Eucalyptus todtiana Pricklybark K Eucalyptus torquata Coral Gum K Eucalyptus youngiana W Eucalyptus victrix K Eucalyptus websteriana K Hakea laurina Pincushion Hakea NL, W Hakea multilineata Grass-leaf Hakea K Hakea petiolaris subsp. -

Copy of Lake King Townsite 2006-7

Lake King Townsite UCL Vegetation And Flora Survey BOTANICAL CONSULTANTS REPORT FOR THE LAKE GRACE SHIRE BY ANNE (COATES) RICK PO Box 36 NEWDEGATE WA 6355 Telephone (08) 98206048 Facsimile (08) 98206047 2007 Table of Contents Lake King UCL Vegetation and Flora Survey 1.0 Introduction --------------------------------------------------------------- 3 2.0 Method --------------------------------------------------------------------- 3 3.0 Results --------------------------------------------------------------------- 7 3.1 Vegetation Survey---------------------------------------------- 7 3.1.1 Previous surveys--------------------------------------- 7 3.1.2 Current Survey----------------------------------------- 7 3.1.3 Vegetation Condition--------------------------------- 12 3.2 Flora Survey------------------------------------------------------ 13 3.2.1 Flora of the Study Area-------------------------------- 13 3.2.2 Species of Interest-------------------------------------- 14 3.3 Conservation Significance-------------------------------------- 17 3.4 Survey Limitations---------------------------------------------- 17 4.0 Acknowledgments ------------------------------------------------------ 18 5.0 References ----------------------------------------------------------------- 18 Appendix 1 Site Descriptions Appendix 2 Plant Species List List of Figures Figure 1 Location of the Study Area. Figure 2 Vegetation Map of the Study Area Figure 3 Vegetation Condition Map of the Study Area List of Tables Table 1 Muir (1977) System of Vegetation Classification