Marisa Linton, Virtue Or Glory?: Dilemmas of Political Heroism In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hwang, Yin (2014) Victory Pictures in a Time of Defeat: Depicting War in the Print and Visual Culture of Late Qing China 1884 ‐ 1901

Hwang, Yin (2014) Victory pictures in a time of defeat: depicting war in the print and visual culture of late Qing China 1884 ‐ 1901. PhD Thesis. SOAS, University of London http://eprints.soas.ac.uk/18449 Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non‐commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this thesis, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given e.g. AUTHOR (year of submission) "Full thesis title", name of the School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination. VICTORY PICTURES IN A TIME OF DEFEAT Depicting War in the Print and Visual Culture of Late Qing China 1884-1901 Yin Hwang Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the History of Art 2014 Department of the History of Art and Archaeology School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London 2 Declaration for PhD thesis I have read and understood regulation 17.9 of the Regulations for students of the School of Oriental and African Studies concerning plagiarism. I undertake that all the material presented for examination is my own work and has not been written for me, in whole or in part, by any other person. -

THE BRITISH ARMY in the LOW COUNTRIES, 1793-1814 By

‘FAIRLY OUT-GENERALLED AND DISGRACEFULLY BEATEN’: THE BRITISH ARMY IN THE LOW COUNTRIES, 1793-1814 by ANDREW ROBERT LIMM A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY. University of Birmingham School of History and Cultures College of Arts and Law October, 2014. University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT The history of the British Army in the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars is generally associated with stories of British military victory and the campaigns of the Duke of Wellington. An intrinsic aspect of the historiography is the argument that, following British defeat in the Low Countries in 1795, the Army was transformed by the military reforms of His Royal Highness, Frederick Duke of York. This thesis provides a critical appraisal of the reform process with reference to the organisation, structure, ethos and learning capabilities of the British Army and evaluates the impact of the reforms upon British military performance in the Low Countries, in the period 1793 to 1814, via a series of narrative reconstructions. This thesis directly challenges the transformation argument and provides a re-evaluation of British military competency in the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars. -

Roberts & Tilton

ROBERTS & TILTON FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE March 12, 2016 Daniel Joseph Martinez IF YOU DRINK HEMLOCK, I SHALL DRINK IT WITH YOU or A BEAUTIFUL DEATH; player to player, pimp to pimp. (As performed by the inmates of the Asylum of Charenton under the direction of the Marquis de Sade) April 9 – May 21, 2016 Sade: “Justine (or The Misfortunes of Virtue)” 1791 Opening Reception Saturday, April 9th, 6-8pm Roberts & Tilton is pleased to present a new installation by Daniel Joseph Martinez. “IF YOU DRINK HEMLOCK, I SHALL DRINK IT WITH YOU or A BEAUTIFUL DEATH; player to player, pimp to pimp. (As performed by the inmates of the Asylum of Charenton under the direction of the Marquis de Sade)” is an immersive environment referencing Jacques-Louis David’s seminal portrait The Death of Marat (1793). Whereas David’s painting represents a single moment, Martinez’s interpretation is conceived as a mise en scène, constantly oscillating between past and present. Entering the gallery, the viewer is confronted by a pair of aluminum bleachers dividing the gallery space. Monitors depicting slow moving clouds are hung over each set, suggesting windows. In the space carved out between the bleachers are three life-like sculptures of Martinez as Marat, his assassin Charlotte Corday, and of the artist himself. A closer look reveals that while the figures are modeled after the artist’s own body, each appropriate the signifiers specific to their character: a knife; fresh wounds; a bathtub; a chore jacket. Confronting this hyper-awareness of the physical body is the fourth character, who appears in the deadpan recital of Corday’s monologues from Peter Weiss’s play “Marat/Sade” (1963) projected throughout the installation. -

![Annales Historiques De La Révolution Française, 371 | Janvier-Mars 2013, « Robespierre » [En Ligne], Mis En Ligne Le 01 Mars 2016, Consulté Le 01 Juillet 2021](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1461/annales-historiques-de-la-r%C3%A9volution-fran%C3%A7aise-371-janvier-mars-2013-%C2%AB-robespierre-%C2%BB-en-ligne-mis-en-ligne-le-01-mars-2016-consult%C3%A9-le-01-juillet-2021-181461.webp)

Annales Historiques De La Révolution Française, 371 | Janvier-Mars 2013, « Robespierre » [En Ligne], Mis En Ligne Le 01 Mars 2016, Consulté Le 01 Juillet 2021

Annales historiques de la Révolution française 371 | janvier-mars 2013 Robespierre Édition électronique URL : https://journals.openedition.org/ahrf/12668 DOI : 10.4000/ahrf.12668 ISSN : 1952-403X Éditeur : Armand Colin, Société des études robespierristes Édition imprimée Date de publication : 1 mars 2013 ISBN : 978-2-200-92824-7 ISSN : 0003-4436 Référence électronique Annales historiques de la Révolution française, 371 | janvier-mars 2013, « Robespierre » [En ligne], mis en ligne le 01 mars 2016, consulté le 01 juillet 2021. URL : https://journals.openedition.org/ahrf/12668 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/ahrf.12668 Ce document a été généré automatiquement le 1 juillet 2021. Tous droits réservés 1 SOMMAIRE Introduction « Je vous laisse ma mémoire […] » Michel Biard Articles La souscription nationale pour sauvegarder les manuscrits de Robespierre : introspection historique d’une initiative citoyenne et militante Serge Aberdam et Cyril Triolaire Les manuscrits de Robespierre Annie Geffroy Les factums de l’avocat Robespierre. Les choix d’une défense par l’imprimé Hervé Leuwers Robespierre dans les publications françaises et anglophones depuis l’an 2000 Marc Belissa et Julien Louvrier Robespierre libéral Yannick Bosc Robespierre et la guerre, une question posée dès 1789 ? Thibaut Poirot « Mes forces et ma santé ne peuvent suffire ». crises politiques, crises médicales dans la vie de Maximilien Robespierre, 1790-1794 Peter McPhee Robespierre et l’authenticité révolutionnaire Marisa Linton Sources Maximilien de Robespierre, élève à Louis-le-Grand (1769-1781). Les apports de la comptabilité du « collège d’Arras » Hervé Leuwers Nouvelles pièces sur Robespierre et les colonies en 1791 Jean-Daniel Piquet Annales historiques de la Révolution française, 371 | janvier-mars 2013 2 Comptes rendus Lia van der HEIJDEN et Jan SANDERS (éds.), De Levensloop van Adriaan van der Willingen (1766-1841). -

Analysing the High Art of Propaganda During the French Revolution

Thema Close to the Source: Analysing the High Art of Propaganda during the French Revolution Jacques-Louis David’s The Death of Marat reveals the blurred lines between historical fact and fiction. Cam Wilson, undergraduate student, The University of Melbourne Analysing primary source material is both an The Death of Marat (1793, see Figure 1) by Jacques- important and highly rewarding exercise in historical Louis David is a uniquely complex historical source scholarship. The ability to critically examine and that captures both the brutal reality and the elaborate evaluate primary documents is the foundation of fiction of the French Revolution. The tragic depiction quality historical research. Analysis requires historians of Jean-Paul Marat, the radical journalist and political to look far beyond first impressions of a historical agitator lying dead in his bath, reveals the methods source. They must examine it in fine detail and be employed by political propagandists to manufacture able to communicate their description to the reader. a new ideological reality for the revolutionary state. Reconstructing the historical context of the source Simultaneously, it serves to accentuate the sense of both deepens the analysis and frequently provides tragedy and death the revolution has left in its wake. This analysis examines the multiple meanings of inspiration for further research. Armed with detailed David’s iconic painting to explain how a historical research and observation, the focus of the analysis source with such a deliberate political agenda can is to uncover the intentions of the author and the reveal so much about revolutionary France. message they are trying to convey. -

Voices of Revolt Voices of Revolt

VOICES OF REVOLT VOICES OF REVOLT SPEECHES OF MAXIMILIEN ROBESPIERRE VOICES OF REVOLT VOLUME I * SPEECHES OF MAXI MILlEN ROBES PIERRE WITH A BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH NEW YORK INTERNATIONAL PUBLISHERS Copyright, 1927, by INTERNATIONAL PUBLISHERS, INc. Printed in the U. S . .A. This book is composed and printed by union labor CONTENTS PAGE INTRODUCTION 9 Robespierre in the Club of the Jacobins 18 Robespierre as the Realpolitiker of the Revo- lution 22 Robespierre and the Committee of Public Safety 2 7 The Ninth Thermidor 36 THE FLIGHT OF THE KING 41 AsKING THE DEATH PENALTY FOR Louis XVI 46 CoNCERNING THE DECLARATION OF THE RIGHTS OF MAN AND OF THE CITIZEN 52 IN FAVOR OF AN ARMED PEOPLE, OF A wAR AGAINsT THE VENDEE s6 REPORT ON THE PRINCIPLES OF A REVOLUTIONARY GOVERNMENT 61 REPORT ON THE PRINCIPLES OF POLITICAL MORAL ITY • REPORT ON THE EXTERNAL SITUATION OF THE REPUBLIC • EXPLANATORY NOTES MAXIMILIEN ROBESPIERRE INTRODUCTION IN the year 1770 a boy knocked at the gate of the Lycee Louis-le-Grand. Mass was just being held, and the youth could still hear the last notes of the organ as he was resting on a bench. He had covered a long distance on his journey: he had come from Arras. "Praised be Jesus Christ," was the sexton's greet ing as he opened the gate. The boy had already been announced, and was at once led to the rector. "So your name is Maximilien Robespierre, my child?" asked the Jesuit who conducted the insti tution. The young man becomes a scholar, one of the most diligent students of the Lycee Louis-le Grand. -

Fair Shares for All

FAIR SHARES FOR ALL JACOBIN EGALITARIANISM IN PRACT ICE JEAN-PIERRE GROSS This study explores the egalitarian policies pursued in the provinces during the radical phase of the French Revolution, but moves away from the habit of looking at such issues in terms of the Terror alone. It challenges revisionist readings of Jacobinism that dwell on its totalitarian potential or portray it as dangerously Utopian. The mainstream Jacobin agenda held out the promise of 'fair shares' and equal opportunities for all in a private-ownership market economy. It sought to achieve social justice without jeopardising human rights and tended thus to complement, rather than undermine, the liberal, individualist programme of the Revolution. The book stresses the relevance of the 'Enlightenment legacy', the close affinities between Girondins and Montagnards, the key role played by many lesser-known figures and the moral ascendancy of Robespierre. It reassesses the basic social and economic issues at stake in the Revolution, which cannot be adequately understood solely in terms of political discourse. Past and Present Publications Fair shares for all Past and Present Publications General Editor: JOANNA INNES, Somerville College, Oxford Past and Present Publications comprise books similar in character to the articles in the journal Past and Present. Whether the volumes in the series are collections of essays - some previously published, others new studies - or mono- graphs, they encompass a wide variety of scholarly and original works primarily concerned with social, economic and cultural changes, and their causes and consequences. They will appeal to both specialists and non-specialists and will endeavour to communicate the results of historical and allied research in readable and lively form. -

“Marat Sade”, the Play, Comes to SISSA

“Marat Sade”, the play, comes to SISSA A new play put on by CUT and open to the public 28 October, 6.30 pm SISSA, “P. Budinich” Main Lecture Hall Via Bonomea 265, Trieste Second appointment with the Trieste University Theatre Centre (CUT) at the International School for Advanced Studies (SISSA) of Trieste. Following the success of the “Merry Wives of Windsor”, now it’s the turn of “Marat Sade”, a play loosely based on the text by Peter Weiss “The Persecution and Assassination of Jean-Paul Marat as Performed by the Inmates of the Asylum of Charenton Under the Direction of the Marquis de Sade”. Admission is free and open to the public. In 1804, among the inmates of the Charenton asylum is also the Marquis de Sade who, thanks to the Director’s enlightened and progressive views, decides to have the inmates enact the last day in the life of the French revolutionary Marat, assassinated by Charlotte Corday, a young woman from Caen who is prepared to sacrifice her life to spare France the excesses of the Revolution. This is the background in which the story of “Marat Sade” unfolds. The play will be performed by CUT on the stage of the “P. Budinich” Main Lecture Hall of SISSA in Trieste on 28 October. In the play, directed by Aldo Vivoda and Valentina Milan, the inmates’ theatrical performance revolves around the remote dialogue between Marat and Sade. The content of their dialogues, motor of action of each scene, touches upon different philosophical, scientific and political issues and perfectly blends in with the atmosphere of study, research and reflection that characterises SISSA. -

Chapter 1. Introduction 1. Jean Tulard, Le My the De Napoleon

Notes Chapter 1. Introduction 1. Jean Tulard, Le My the de Napoleon (Paris: Armand Colin, 1971), pp.47, 51 etc. 2. Addicts may consult Jean Savant, Napoleon (Paris: Veyrier, 1974); Frank Richardson, Napoleon, Bisexual Emperor (London: Kimber, 1972); Arno Karlen, Napoleon's Glands and Other Ventures in Biohistory (Boston: Little Brown, 1984). 3. J.M. Thompson, Napoleon Bonaparte (Oxford: Blackwell, 1988), p.389. 4. J. Tulard, Napoleon: The Myth of the Saviour, trans. T. Waugh (London: Methuen, 1985), p.449. For the poisoning allegations, see Sten Forshufvud and Ben Weider, Assassination at St Helena: The Poisoning of Napoleon Bonaparte (Vancouver: Mitchell Press, 1978), and Frank Richardson, Napoleon's Death: An Inquest (London: Kimber, 1974). 5. G. Ellis, Napoleon's Continental Blockade: The Case ofAlsace (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1981); Alan Forrest, Conscripts and Deserters: The Army and French Society during the Revolution and Empire (New York: Oxford University Press, 1989); Michael Broers, The Restoration of Order in Napoleonic Piedmont, 1797-1814, unpublished Oxford D .Phil. thesis, 1986. Chapter 2. Bonaparte the Jacobin 1. J. Boswell, An Account of Corsica, the Journal of a Tour in that Island and Memoirs ofPascal Paoli (London, 1768). 2. Peter A. Thrasher, Pasquale Paoli: an Enlightened Hero, 1725-1807 (London: Constable, 1970), e.g. pp.98-9. 3. D. Carrington, "Paoli et sa 'Constitution' (1755-69)", AhRf, 218, October-December, 1974,531. 4. J. Tulard, Napoleon: The Myth of the Saviour (London: Methuen, 1985), p.24. 301 302 NOTES 5. S.F. Scott, The Response of the Rnyal Army to the French Revolution: The Rnle and Development of the Line Army during 1789-93, (Oxford, 1978). -

The Cult of the Martyrs of Liberty

THE CULT OF THE MARTYRS OF LIBERTY: RADICAL RELIGIOSITY IN THE FRENCH REVOLUTION A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of Graduate Studies of The University of Guelph by ASHLEY SHIFFLETT In partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of Master of Arts July 2008 © Ashley Shifflett, 2008. Library and Bibliotheque et 1*1 Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-42839-9 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-42839-9 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par Plntemet, prefer, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans loan, distribute and sell theses le monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, electronique commercial purposes, in microform, et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. this thesis. Neither the thesis Ni la these ni des extraits substantiels de nor substantial extracts from it celle-ci ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement may be printed or otherwise reproduits sans son autorisation. -

The French Revolution in the French-Algerian War (1954-1962): Historical Analogy and the Limits of French Historical Reason

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 9-2016 The French Revolution in the French-Algerian War (1954-1962): Historical Analogy and the Limits of French Historical Reason Timothy Scott Johnson The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/1424 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] THE FRENCH REVOLUTION IN THE FRENCH-ALGERIAN WAR (1954-1962): HISTORICAL ANALOGY AND THE LIMITS OF FRENCH HISTORICAL REASON By Timothy Scott Johnson A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2016 © 2016 TIMOTHY SCOTT JOHNSON All Rights Reserved ii The French Revolution in the French-Algerian War (1954-1962): Historical Analogy and the Limits of French Historical Reason by Timothy Scott Johnson This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in History in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Richard Wolin, Distinguished Professor of History, The Graduate Center, CUNY _______________________ _______________________________________________ Date Chair of Examining Committee _______________________ -

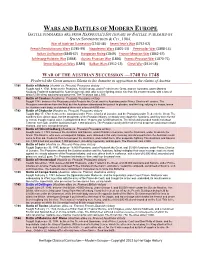

Wars and Battles of Modern Europe Battle Summaries Are from Harbottle's Dictionary of Battles, Published by Swan Sonnenschein & Co., 1904

WARS AND BATTLES OF MODERN EUROPE BATTLE SUMMARIES ARE FROM HARBOTTLE'S DICTIONARY OF BATTLES, PUBLISHED BY SWAN SONNENSCHEIN & CO., 1904. War of Austrian Succession (1740-48) Seven Year's War (1752-62) French Revolutionary Wars (1785-99) Napoleonic Wars (1801-15) Peninsular War (1808-14) Italian Unification (1848-67) Hungarian Rising (1849) Franco-Mexican War (1862-67) Schleswig-Holstein War (1864) Austro Prussian War (1866) Franco Prussian War (1870-71) Servo-Bulgarian Wars (1885) Balkan Wars (1912-13) Great War (1914-18) WAR OF THE AUSTRIAN SUCCESSION —1740 TO 1748 Frederick the Great annexes Silesia to his domains in opposition to the claims of Austria 1741 Battle of Molwitz (Austria vs. Prussia) Prussians victory Fought April 8, 1741, between the Prussians, 30,000 strong, under Frederick the Great, and the Austrians, under Marshal Neuperg. Frederick surprised the Austrian general, and, after severe fighting, drove him from his entrenchments, with a loss of about 5,000 killed, wounded and prisoners. The Prussians lost 2,500. 1742 Battle of Czaslau (Austria vs. Prussia) Prussians victory Fought 1742, between the Prussians under Frederic the Great, and the Austrians under Prince Charles of Lorraine. The Prussians were driven from the field, but the Austrians abandoned the pursuit to plunder, and the king, rallying his troops, broke the Austrian main body, and defeated them with a loss of 4,000 men. 1742 Battle of Chotusitz (Austria vs. Prussia) Prussians victory Fought May 17, 1742, between the Austrians under Prince Charles of Lorraine, and the Prussians under Frederick the Great. The numbers were about equal, but the steadiness of the Prussian infantry eventually wore down the Austrians, and they were forced to retreat, though in good order, leaving behind them 18 guns and 12,000 prisoners.