The Routledge Companion to Media and Class Class Hybridity and The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Glitz and Glam

FINAL-1 Sat, Feb 24, 2018 5:31:17 PM Glitz and glam The biggest celebration in filmmaking tvspotlight returns with the 90th Annual Academy Your Weekly Guide to TV Entertainment Awards, airing Sunday, March 4, on ABC. Every year, the most glamorous people • For the week of March 3 - 9, 2018 • in Hollywood stroll down the red carpet, hoping to take home that shiny Oscar for best film, director, lead actor or ac- tress and supporting actor or actress. Jimmy Kimmel returns to host again this year, in spite of last year’s Best Picture snafu. OMNI Security Team Jimmy Kimmel hosts the 90th Annual Academy Awards Omni Security SERVING OUR COMMUNITY FOR OVER 30 YEARS Put Your Trust in Our2 Familyx 3.5” to Protect Your Family Big enough to Residential & serve you Fire & Access Commercial Small enough to Systems and Video Security know you Surveillance Remote access 24/7 Alarm & Security Monitoring puts you in control Remote Access & Wireless Technology Fire, Smoke & Carbon Detection of your security Personal Emergency Response Systems system at all times. Medical Alert Systems 978-465-5000 | 1-800-698-1800 | www.securityteam.com MA Lic. 444C Old traditional Italian recipes made with natural ingredients, since 1995. Giuseppe's 2 x 3” fresh pasta • fine food ♦ 257 Low Street | Newburyport, MA 01950 978-465-2225 Mon. - Thur. 10am - 8pm | Fri. - Sat. 10am - 9pm Full Bar Open for Lunch & Dinner FINAL-1 Sat, Feb 24, 2018 5:31:19 PM 2 • Newburyport Daily News • March 3 - 9, 2018 the strict teachers at her Cath- olic school, her relationship with her mother (Metcalf) is Videoreleases strained, and her relationship Cream of the crop with her boyfriend, whom she Thor: Ragnarok met in her school’s theater Oscars roll out the red carpet for star quality After his father, Odin (Hop- program, ends when she walks kins), dies, Thor’s (Hems- in on him kissing another guy. -

Senior Softball Alive and Well by Larry Campbell Softball, Keeps Them Active and There Are Two Bases at First Base

Fundraiser BBQ Supports Local First Responders Wounded Service Members Page 8 Honored by Elks Lodge Page 4 Volume 35 • Issue 36 Serving Carmichael and Sacramento County since 1981 September 4, 2015 THE AGE OF ADELINE Ike’s 103-Year Dancing Feat Caltrans Behaving Badly SACRAMENTO REGION, CA (MPG) - California’s highways are crumbling. It’s a simple fact that we need to send more funding toward fixing our transportation Page 9 infrastructure. Sacramento Democrats believe that funding must come from increased taxes on fuel and fees on drivers. But the knee- jerk reaction to go back to the ATHLON SPORTS public tax trough is unconscio- nable when multiple reports INSIDE BASEBALL continue to show high levels of government waste. Consider the following facts: • A recent report by the California State Auditor Report found that Caltrans approved the timesheets of an engineer who played golf for 55 workdays from August 2012 to March 2014. • The Los Angeles Times recently reported that the gov- ernment email addresses of Page 17 dozens of California state workers were included in the hacked list of users of Ashley Madison, the online dating site for married people, including employees from Caltrans. THE ONES FLYING • A report by the nonpartisan and independent Legislative OVER THE Story and photo by Susan Maxwell Skinner Analyst’s Office recommends eliminating 3,500 redundant CUCKOO NEST positions at Caltrans. The CARMICHAEL, CA (MPG) - Dancing man Isaac “Ike” Ortiz turned 103 on September 3rd. After a birthday dinner at his report found that this would church, he plans to celebrate on the tiles. -

15 ABC Sunday 5/12/2019 9-10A This Week :30

P+PB TV Advertising Schedule: Week of 5/6 NETWORK DAY DATE TIME PROGRAM NAME LENGTH ABC Sunday 5/12/2019 9-10a This Week :15 ABC Sunday 5/12/2019 9-10a This Week :30 BET Monday 5/6/2019 5-6p A Thin Line Between Love and Hate :30 BET Tuesday 5/7/2019 7-8a Fresh Prince of Bel Air :15 BET Tuesday 5/7/2019 10-11a House of Payne :15 BET Tuesday 5/7/2019 2-3p A Thin Line Between Love and Hate :30 BET Tuesday 5/7/2019 4-5p National Security :15 BET Wednesday 5/8/2019 8-9a Meet the Browns :30 BET Wednesday 5/8/2019 5-6p Running Out of Time :15 BET Wednesday 5/8/2019 6-7p Tyler Perry's Good Deed :15 BET Friday 5/10/2019 8-9a Meet the Browns :30 BET Sunday 5/12/2019 9-10a Fresh Prince of Bel Air :30 BRVO Monday 5/6/2019 8-9a Vanderpump Rules :30 BRVO Monday 5/6/2019 11a-12p Vanderpump Rules :15 BRVO Monday 5/6/2019 3-4p Vanderpump Rules :30 BRVO Monday 5/6/2019 12-1a Vanderpump Rules :15 BRVO Tuesday 5/7/2019 10-11a The Real Housewives of Beverly Hills :30 BRVO Tuesday 5/7/2019 2-3p The Real Housewives of Beverly Hills :15 BRVO Tuesday 5/7/2019 6-7p The Real Housewives of Beverly Hills :15 BRVO Wednesday 5/8/2019 8-9a The Real Housewives of New York City :15 BRVO Wednesday 5/8/2019 12-1p Texicanas :15 BRVO Wednesday 5/8/2019 4-5p Southern Charm :15 BRVO Wednesday 5/8/2019 6-7p Southern Charm :15 BRVO Thursday 5/9/2019 9-10a Million Dollar Listing Los Angeles :15 BRVO Thursday 5/9/2019 2-3p Million Dollar Listing Los Angeles :30 BRVO Thursday 5/9/2019 5-6p Million Dollar Listing Los Angeles :30 BRVO Thursday 5/9/2019 1-2a Hollywood Medium with Tyler -

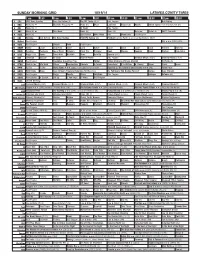

Sunday Morning Grid 12/28/14 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 12/28/14 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Football Chargers at Kansas City Chiefs. (N) Å 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News 1st Look Paid Premier League Goal Zone (N) (TVG) World/Adventure Sports 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) Outback Explore St. Jude Hospital College 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Paid Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football Philadelphia Eagles at New York Giants. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Program Black Knight ›› (2001) 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local Transfor. Transfor. 24 KVCR Painting Dewberry Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexico Cooking Chefs Life Simply Ming Ciao Italia 28 KCET Raggs Play. Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Biz Ed Slott’s Retirement Rescue for 2014! (TVG) Å BrainChange-Perlmutter 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program 34 KMEX Paid Program Al Punto (N) República Deportiva (TVG) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Redemption Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. Conley Super Christ Jesse 46 KFTR Tu Dia Tu Dia Happy Feet ››› (2006) Elijah Wood. -

Wild’ Evaluation Between 6 and 9Years of Age

FINAL-1 Sun, Jul 5, 2015 3:23:05 PM Residential&Commercial Sales and Rentals tvspotlight Vadala Real Proudly Serving Your Weekly Guide to TV Entertainment Cape Ann Since 1975 Estate • For the week of July 11 - 17, 2015 • 1 x 3” Massachusetts Certified Appraisers 978-281-1111 VadalaRealEstate.com 9-DDr. OsmanBabsonRd. Into the Gloucester,MA PEDIATRIC ORTHODONTICS Pediatric Orthodontics.Orthodontic care formanychildren can be made easier if the patient starts fortheir first orthodontic ‘Wild’ evaluation between 6 and 9years of age. Some complicated skeletal and dental problems can be treated much more efficiently if treated early. Early dental intervention including dental sealants,topical fluoride application, and minor restorativetreatment is much more beneficial to patients in the 2-6age level. Parents: Please makesure your child gets to the dentist at an early age (1-2 years of age) and makesure an orthodontic evaluation is done before age 9. Bear Grylls hosts Complimentarysecond opinion foryour “Running Wild with child: CallDr.our officeJ.H.978-283-9020 Ahlin Most Bear Grylls” insurance plans 1accepted. x 4” CREATING HAPPINESS ONE SMILE AT ATIME •Dental Bleaching included forall orthodontic & cosmetic dental patients. •100% reduction in all orthodontic fees for families with aparent serving in acombat zone. Call Jane: 978-283-9020 foracomplimentaryorthodontic consultation or 2nd opinion J.H. Ahlin, DDS •One EssexAvenue Intersection of Routes 127 and 133 Gloucester,MA01930 www.gloucesterorthodontics.com Let ABCkeep you safe at home this Summer Home Healthcare® ABC Home Healthland Profess2 x 3"ionals Local family-owned home care agency specializing in elderly and chronic care 978-281-1001 www.abchhp.com FINAL-1 Sun, Jul 5, 2015 3:23:06 PM 2 • Gloucester Daily Times • July 11 - 17, 2015 Adventure awaits Eight celebrities join Bear Grylls for the adventure of a lifetime By Jacqueline Spendlove TV Media f you’ve ever been camping, you know there’s more to the Ifun of it than getting out of the city and spending a few days surrounded by nature. -

Sunday Morning Grid 5/1/16 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 5/1/16 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program Boss Paid Program PGA Tour Golf 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News Rescue Red Bull Signature Series (Taped) Å Hockey: Blues at Stars 5 CW News (N) Å News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) NBA Basketball First Round: Teams TBA. (N) Basketball 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Pastor Mike Woodlands Amazing Paid Program 11 FOX In Touch Paid Fox News Sunday Midday Prerace NASCAR Racing Sprint Cup Series: GEICO 500. (N) 13 MyNet Paid Program A History of Violence (R) 18 KSCI Paid Hormones Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local 24 KVCR Landscapes Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexico Martha Pépin Baking Simply Ming 28 KCET Wunderkind 1001 Nights Bug Bites Space Edisons Biz Kid$ Celtic Thunder Legacy (TVG) Å Soulful Symphony 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Leverage Å Leverage Å Leverage Å Leverage Å 34 KMEX Conexión En contacto Paid Program Fútbol Central (N) Fútbol Mexicano Primera División: Toluca vs Azul República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Schuller In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Pathway Super Kelinda Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Program Formula One Racing Russian Grand Prix. -

Sunday Morning Grid 10/19/14 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 10/19/14 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Paid Program Bull Riding 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News (N) Meet LazyTown Poppy Cat Noodle Action Sports From Brooklyn, N.Y. (N) 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) News Å Vista L.A. ABC7 Presents 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Winning Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football Carolina Panthers at Green Bay Packers. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Program I.Q. ››› (1994) (PG) 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local Transfor. Transfor. 24 KVCR Painting Dewberry Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Cook Mexico Cooking Cook Kitchen Ciao Italia 28 KCET Raggs Cold. Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Biz Special (TVG) 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program Criminal Minds (TV14) Criminal Minds (TV14) 34 KMEX Paid Program República Deportiva (TVG) Fútbol Fútbol Mexicano Primera División Al Punto (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Redemption Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. Conley Super Christ Jesse 46 KFTR Tu Dia Tu Dia Home Alone 4 ›› (2002, Comedia) French Stewart. -

Philadelphia and the Southern Elite: Class, Kinship, and Culture in Antebellum America

PHILADELPHIA AND THE SOUTHERN ELITE: CLASS, KINSHIP, AND CULTURE IN ANTEBELLUM AMERICA BY DANIEL KILBRIDE A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 1997 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS In seeing this dissertation to completion I have accumulated a host of debts and obligation it is now my privilege to acknowledge. In Philadelphia I must thank the staff of the American Philosophical Society library for patiently walking out box after box of Society archives and miscellaneous manuscripts. In particular I must thank Beth Carroll- Horrocks and Rita Dockery in the manuscript room. Roy Goodman in the Library’s reference room provided invaluable assistance in tracking down secondary material and biographical information. Roy is also a matchless authority on college football nicknames. From the Society’s historian, Whitfield Bell, Jr., I received encouragement, suggestions, and great leads. At the Library Company of Philadelphia, Jim Green and Phil Lapansky deserve special thanks for the suggestions and support. Most of the research for this study took place in southern archives where the region’s traditions of hospitality still live on. The staff of the Mississippi Department of Archives and History provided cheerful assistance in my first stages of manuscript research. The staffs of the Filson Club Historical Library in Louisville and the Special Collections room at the Medical College of Virginia in Richmond were also accommodating. Special thanks go out to the men and women at the three repositories at which the bulk of my research was conducted: the Special Collections Library at Duke University, the Southern Historical Collection of the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, and the Virginia Historical Society. -

Patterns of Middle and Upper Class Homicide Edward Green

Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology Volume 70 Article 4 Issue 2 Summer Summer 1979 Patterns of Middle and Upper Class Homicide Edward Green Russell P. Wakefield Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/jclc Part of the Criminal Law Commons, Criminology Commons, and the Criminology and Criminal Justice Commons Recommended Citation Edward Green, Russell P. Wakefield, Patterns of Middle and Upper Class Homicide, 70 J. Crim. L. & Criminology 172 (1979) This Criminology is brought to you for free and open access by Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology by an authorized editor of Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. 9901-4169/79/7002-0172S02.00/0 THE JOURNAL OF CRIMINAL LAW & CRIMINOLOGY Vol. 70, No. 2 Copyright © 1979 by Northwestern University School of Law Printedin U.S.A. PATTERNS OF MIDDLE AND UPPER CLASS HOMICIDE EDWARD GREEN* AND RUSSELL P. WAKEFIELD" INTRODUCTION 1. Black males from 15 to 30 years of age kill more frequently than any other racial age-sex cate- The study of crime has traditionally focused gory. upon the conventional criminal behavior patterns 2. As many as 64% of offenders and 47% of victims of the lower classes. Not until Sutherland's seminal have prior criminal records. work on white-collar crime did researchers improve 3. From one-half to two-thirds of homicides are the representativeness of the subject matter of crim- unpremeditated crimes of passion arising out of inology by studying the crimes of the rich as well altercations over matters which, from a middle as those of the poor.' This development shows that class perspective, hardly warrant so extreme a predatory crime is not exclusively, necessarily, or response. -

Schools Struggle to Deal with Special Needs Pupils

Amazon Videos Feedback Like 1.8m Follow @MailOnline DailyMail Wednesday, Jul 23rd 2014 6AM 69°F 9AM 68°F 5-Day Forecast Home U.K. News Sports U.S. Showbiz Australia Femail Health Science Money Video Travel Columnists News Home Arts Headlines Pictures Most read News Board Wires Login The sad final Tragedy as college John Travolta can't Can't sleep in the Obamacare in How happy is your The Queen must not journey home: graduate, 26, dies stop former pilot heat? Put your chaos as federal city? Study says have shellfish and Schools struggle to deal with Site Web special needs pupils - condemning them to poor education By LAURA CLARK Last updated at 01:08 14 December 2007 open in browser PRO version Are you a developer? Try out the HTML to PDF API pdfcrowd.com Sending children with severe special needs to ordinary schools condemns many to a poor education and disrupts lessons, a report warns today. Schools too often lack expertise and resources to cater for pupils with behavioural or learning problems, it claims. In the worst cases, heads are forced to expel the youngsters, raising the chances they will drift into crime. Scroll down for more ... Ads by Google University of Phoenix phoenix.edu Official Site. Online The report reveals how growing numbers of pupils are being classed as having Programs. Flexible special educational needs, with schools seeking extra cash to help cope with them. Like Follow Daily Mail @dailymailus Scheduling. Get One in five primary children is classed as having a behavioural problem, disability or Info. -

Heleieth I. B. Saffioti. Women in Class Society

Women in Class Society by Heleith I. B. Saffioti Women in Class Society by Heleith I. B. Saffioti Review by: Barbara Celarent American Journal of Sociology, Vol. 119, No. 6 (May 2014), pp. 1821-1827 Published by: The University of Chicago Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/677208 . Accessed: 12/09/2014 18:48 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The University of Chicago Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to American Journal of Sociology. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 128.135.12.127 on Fri, 12 Sep 2014 18:48:41 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions Book Reviews describes the writings he studies as examples of the “deviance memoir genre,” with many a tall tale, much lying and self-vindication along the lines of once I was lost, now I am found and do good works. He takes the key supposed facts in a story and examines how the author rhetorically exculpates him- or herself. The fact that a distinguished historian like the late Eric Hobsbawm does not deal with the gossip Goode alleges about his private life means his memoir is of little interest and merely confirms his typically Marxist re- luctance to face up to the real issues of life, as opposed to fascism, the Ho- locaust, and the Jewish experience. -

Bryce Dallas Howard Salutes

INSIDE THIS ISSUE Horoscopes ........................................................... 2 Now Streaming ...................................................... 2 Puzzles ................................................................... 4 TV Schedules ......................................................... 5 Remembering The timelessness “One Day At A Time” Top 10 ................................................................... 6 6 Carrie Fisher 6 of Star Wars 7 gets animated Home Video .......................................................... 7 June 13 - June 19, 2020 Bryce Dallas Howard salutes ‘Dads’ – They’re not who you think they are BY GEORGE DICKIE with a thick owner’s manual but his newborn child “The interview with my grandfather was something Ask 100 different men what it means to be a father could have none. that I did in 2013,” she says, “... and that was kind and you’ll likely get 100 different answers. Which is The tone is humorous and a lot of it comes from of an afterthought as well where it was like, ‘Oh something Bryce Dallas Howard found when making the comics, who Howard felt were the ideal people to my gosh, I interviewed Grandad. I wonder if there’s anything in there.’ And so I went back and rewatched a documentary that begins streaming in honor of describe the paternal condition. his tapes and found that story.” Father’s Day on Apple TV+. “Stand-up comedians, they are prepared,” she says with a laugh. “They’re looking at their lives through What comes through is there is no one definition of In “Dads,” an