Photoshop Landscapes: Digital Mediations and Bollywood Cities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ASIA COLLOQUIA PAPERS 2014 Critical Approaches to South Asian Studies Workshop

ASIA COLLOQUIA PAPERS 2014 Critical Approaches to South Asian Studies Workshop Vol. 05 No. 02 // 2015 Bollywood’s Queer Dostana: Articulating a Transnational Queer Indian Identity and Family in 2008’s Dostana Mainstream ‘masala’ Bollywood films have played a key role in ABOUT THE AUTHOR producing and reiterating a nationalist Indian identity centered Aaron Rohan George on the monolithic notion of the Hindu, wealthy and patriarchal MA in Media Studies India. The result of such attenuated discourses has been a Faculty of Information and Media great limitation on who gets included in the signifier ‘Indian’. Studies University of Western Ontario Though, as I posit in this paper, these very mainstream ‘masala’ Bollywood films have at times also offered the opportunity to contest this culturally conflated Indian identity by acting as a heterotopic space – a subversive space for not only the reiteration of the hegemonic social reality but also a space where it can be contested. Particularly relevant here is the role of these films in shaping conceptions of queer desire and sexuality. This paper is an analysis of the 2008 Bollywood film, Dostana, and its role as a heterotropic space for the creation of a new queer transnational Indian identity and family. I posit that Dostana presented a new queer Indian identity, independent of the historicized, right wing, socio- cultural conceptions of queer desire and bodies prevailing in India. In doing so, I will argue that the film creates a nascent queer gaze through its representation of queered desire, bodies and the Indian family unity – moving the queer Indian identity out of its heteorpatriarchal closet and into the centre of transnational, mainstream Indian culture. -

Banal Dreams

Banal Dreams Bombay Dreams is a hodge-podge of clichéd, uninspiring lines meshed together to punctuate one dance number from the next. Shekhar Deshpande Broadway is that great New York institution. Like everything else, and unlike Disney World, it is a mixed bag. There are some shows and some theater. The shows are nothing but a tourist attraction. It is a thing to do along with an expensive meal, a trip around town, preferably with a date of your choice and often a ritual with someone who needs to be courted for one reason or another. Theater on the other hand, such as it is in the age of mass produced media, is a rare and small art form that thrives in some corners. Theater is self-conscious; Broadway shows are not. The latter are a shameless exercise in showmanship. But some people like it. It is hard to figure out the reaction of the audience to Bombay Dreams. They seem to be responsive, mostly people of European origins. They were laughing, clapping and generally quite engaged with the production. So when one writes about Bombay Dreams, this becomes an essential ingredient. Perhaps Bombay Dreams, that celebrated production that arrived here from the U.K. with inspiration and guidance from Andrew Lloyd Webber and Shekhar Kapoor, serves the needs of tourists. It offers a good example of the kind of showmanship they expect, an exotic stop on their tourist route and perhaps a palatable taste of what we have come to call Bollywood. Bombay Dreams begins with an invocation of the magic of Bollywood. -

Bombay Dreams2

Bombay Dreams Judith van Praag Mark your calendars for Bollywood is coming to town! Seattle's 5th Avenue Theatre is the final stop on the National Tour of "Bombay Dreams". Entranced by the allure of Bollywood movies and the music of celebrated Indian composer A.R. Rahman (The Lord of the Rings: The Musical) filmmaker Shekhar Kapur and Andrew Lloyd Webber came up with the idea of a Bolllywood based musical. Bollywood is the epicenter of the thriving South Asian film industry, India's answer to Hollywood. Bollywood films already show the elements of a musical: song and dance. But Bollywood films offer more than that; they are extravaganzas complete with comedy and daredevil thrills. The plots are usually melodramatic and frequently employ familiar story lines such as: star-crossed lovers, angry meddling parents, love triangles and conniving villains. "Bombay Dreams" tells the story of Akaash (Sachin Bhatt – known for The Asian/European tour of West Side Story, Aida at the Gateway Playhouse), a handsome young tour guide from the slums of Bombay who dreams of becoming the next Bollywood star, the object of his desire Priya (Reshma Shetty – known for West Side Story, La Boheme, Don Giovanni) and all the complications that arise when Akaash faces fame, fortune, and the obligations to his family, friends and Paradise slum. The plot includes frequent reference to the city's change of name from Bombay to Mumbai, as well as the accompanying identity issues. This musical journey within "Bombay Dreams" is an exploration of the importance of cultural heritage, the price of success, the bonds of friendship and the power of true love. -

Yash Chopra the Legend

YASH CHOPRA THE LEGEND Visionary. Director. Producer. Legendary Dream Merchant of Indian Cinema. And a trailblazer who paved the way for the Indian entertainment industry. 1932 - 2012 Genre defining director, star-maker and a studio mogul, Yash Chopra has been instrumental in shaping the symbolism of mainstream Hindi cinema across the globe. Popularly known as the ‘King of Romance’ for his string of hit romantic films spanning over a five-decade career, he redefined drama and romance onscreen. Born on 27 September 1932, Yash Chopra's journey began from the lush green fields of Punjab, which kept reappearing in his films in all their splendour. © Yash Raj Films Pvt. Ltd. 1 www.yashrajfilms.com Yash Chopra started out as an assistant to his brother, B. R. Chopra, and went on to direct 5 very successful films for his brother’s banner - B. R. Films, each of which proved to be a significant milestone in his development as a world class director of blockbusters. These were DHOOL KA PHOOL (1959), DHARMPUTRA (1961), WAQT (1965) - India’s first true multi-starrer generational family drama, ITTEFAQ (1969) & AADMI AUR INSAAN (1969). He has wielded the baton additionally for 4 films made by other film companies - JOSHILA (1973), DEEWAAR (1975), TRISHUL (1978) & PARAMPARA (1993). But his greatest repertoire of work were the 50 plus films made under the banner that he launched - the banner that stands for the best of Hindi cinema - YRF. Out of these films, he directed 13 himself and these films have defined much of the language of Hindi films as we know them today. -

Bollywood in Australia: Transnationalism and Cultural Production

University of Wollongong Research Online Faculty of Arts - Papers (Archive) Faculty of Arts, Social Sciences & Humanities 1-1-2010 Bollywood in Australia: Transnationalism and Cultural Production Andrew Hassam University of Wollongong, [email protected] Makand Maranjape Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/artspapers Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons, and the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Hassam, Andrew and Maranjape, Makand, Bollywood in Australia: Transnationalism and Cultural Production 2010. https://ro.uow.edu.au/artspapers/258 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] Introduction Bollywood in Australia Andrew Hassam and Makand Paranjape The global context of Bollywood in Australia Makarand Paranjape The transcultural character and reach of Bollywood cinema has been gradually more visible and obvious over the last two decades. What is less understood and explored is its escalating integration with audiences, markets and entertainment industries beyond the Indian subcontinent. This book explores the relationship of Bollywood to Australia. We believe that this increasingly important relationship is an outcome of the convergence between two remarkably dynamic entities—globalising Bollywood, on the one hand and Asianising Australia, on the other. If there is a third element in this relationship, which is equally important, it is the mediating power of the vibrant diasporic community of South Asians in Australia. Hence, at its most basic, this book explores the conjunctures and ruptures between these three forces: Bollywood, Australia and their interface, the diaspora. 1 Bollywood in Australia It would be useful to see, at the outset, how Bollywood here refers not only to the Bombay film industry, but is symbolic of the Indian and even the South Asian film industry. -

Ta Ra Pum Pum Song

Ta ra pum pum song click here to download There is nothing more important than family love! Listen to the most loved song, Ta Ra Rum Pum! Watch Full. the song Ta ra rum pum from the movie Ta ra rum pum. Release Date: 27 April ▻ Buy from iTunes - www.doorway.ru Watch Full Movie: ▻ Google Play - http://goo. Ta Ra Rum Pum. Indian Cinema · · No labels. Watch from $ When RV (Saif Ali Khan) is spotted by. If it's not forever, it's not love. Profess your loved to your loved one with this fun song 'Ab To Forever' from. Ta Ra Rum Pum is a Indian Hindi sports-drama film that stars Saif Ali Khan and Rani Mukerji in the lead roles. This is the second time the lead pair worked together after the success of their last film, Hum Tum (). It was directed by Siddharth Anand, who directed 's Salaam Namaste (Also starring Khan), and Story by: Nishant Shah. QUALITY: HD SONG: Tara Ra Ra Rum Pum MOVIE: [Tara Rum Pam Pam] ALL RIGHTS OF THIS SONG ARE. Watch the video «Ta Ra Ra Ra Rum Song- Ta Ra Rum Pum HD - Saif Ali Khan | Rani Mukerji. Song Name, ( Kbps). Ta Ra Rum Pum, Download. Hey Shona, Download. Nachle Ve, Download. Ta Ra Ra Ra Rum TaRaRumPum, Download. Ab To Forever, Download. Saaiyaan, Download. Ta Ra Rum Pum Free Mp3 Download Ta Ra Rum Pum Song Free Download Ta Ra Rum Pum Hindi Movie Mp3 Download Ta Ra Rum Pum Video Download Ta Ra Rum Pum Free Music Download Ab To Forever Kk/,Shreya Ghoshal/,Vishal Dadlani/,Hey Shona Shaan/,Sunidhi. -

New and Bestselling Titles Sociology 2016-2017

New and Bestselling titles Sociology 2016-2017 www.sagepub.in Sociology | 2016-17 Seconds with Alice W Clark How is this book helpful for young women of Any memorable experience that you hadhadw whilehile rural areas with career aspirations? writing this book? Many rural families are now keeping their girls Becoming part of the Women’s Studies program in school longer, and this book encourages at Allahabad University; sharing in the colourful page 27A these families to see real benefit for themselves student and faculty life of SNDT University in supporting career development for their in Mumbai; living in Vadodara again after daughters. It contributes in this way by many years, enjoying friends and colleagues; identifying the individual roles that can be played reconnecting with friendships made in by supportive fathers and mothers, even those Bangalore. Being given entrée to lively students with very little education themselves. by professors who cared greatly about them. Being treated wonderfully by my interviewees. What facets of this book bring-in international Any particular advice that you would like to readership? share with young women aiming for a successful Views of women’s striving for self-identity career? through professionalism; the factors motivating For women not yet in college: Find supporters and encouraging them or setting barriers to their in your family to help argue your case to those accomplishments. who aren’t so supportive. Often it’s submissive Upward trends in women’s education, the and dutiful mothers who need a prompt from narrowing of the gender gap, and the effects a relative with a broader viewpoint. -

2 Apar Gupta New Style Complete.P65

INDIAN LAWYERS IN POPULAR HINDI CINEMA 1 TAREEK PAR TAREEK: INDIAN LAWYERS IN POPULAR HINDI CINEMA APAR GUPTA* Few would quarrel with the influence and significance of popular culture on society. However culture is vaporous, hard to capture, harder to gauge. Besides pure democracy, the arts remain one of the most effective and accepted forms of societal indicia. A song, dance or a painting may provide tremendous information on the cultural mores and practices of a society. Hence, in an agrarian community, a song may be a mundane hymn recital, the celebration of a harvest or the mourning of lost lives in a drought. Similarly placed as songs and dance, popular movies serve functions beyond mere satisfaction. A movie can reaffirm old truths and crystallize new beliefs. Hence we do not find it awkward when a movie depicts a crooked politician accepting a bribe or a television anchor disdainfully chasing TRP’s. This happens because we already hold politicians in disrepute, and have recently witnessed sensationalistic news stories which belong in a Terry Prachet book rather than on prime time news. With its power and influence Hindi cinema has often dramatized courtrooms, judges and lawyers. This article argues that these dramatic representations define to some extent an Indian lawyer’s perception in society. To identify the characteristics and the cornerstones of the archetype this article examines popular Bollywood movies which have lawyers as its lead protagonists. The article also seeks solutions to the lowering public confidence in the legal profession keeping in mind the problem of free speech and censorship. -

Akshay Kumar

Akshay Kumar Topic relevant selected content from the highest rated wiki entries, typeset, printed and shipped. Combine the advantages of up-to-date and in-depth knowledge with the convenience of printed books. A portion of the proceeds of each book will be donated to the Wikimedia Foundation to support their mis- sion: to empower and engage people around the world to collect and develop educational content under a free license or in the public domain, and to disseminate it effectively and globally. The content within this book was generated collaboratively by volunteers. Please be advised that nothing found here has necessarily been reviewed by people with the expertise required to provide you with complete, accu- rate or reliable information. Some information in this book maybe misleading or simply wrong. The publisher does not guarantee the validity of the information found here. If you need specific advice (for example, medi- cal, legal, financial, or risk management) please seek a professional who is licensed or knowledgeable in that area. Sources, licenses and contributors of the articles and images are listed in the section entitled “References”. Parts of the books may be licensed under the GNU Free Documentation License. A copy of this license is included in the section entitled “GNU Free Documentation License” All used third-party trademarks belong to their respective owners. Contents Articles Akshay Kumar 1 List of awards and nominations received by Akshay Kumar 8 Saugandh 13 Dancer (1991 film) 14 Mr Bond 15 Khiladi 16 Deedar (1992 film) 19 Ashaant 20 Dil Ki Baazi 21 Kayda Kanoon 22 Waqt Hamara Hai 23 Sainik 24 Elaan (1994 film) 25 Yeh Dillagi 26 Jai Kishen 29 Mohra 30 Main Khiladi Tu Anari 34 Ikke Pe Ikka 36 Amanaat 37 Suhaag (1994 film) 38 Nazar Ke Samne 40 Zakhmi Dil (1994 film) 41 Zaalim 42 Hum Hain Bemisaal 43 Paandav 44 Maidan-E-Jung 45 Sabse Bada Khiladi 46 Tu Chor Main Sipahi 48 Khiladiyon Ka Khiladi 49 Sapoot 51 Lahu Ke Do Rang (1997 film) 52 Insaaf (film) 53 Daava 55 Tarazu 57 Mr. -

Koel Chatterjee Phd Thesis

Bollywood Shakespeares from Gulzar to Bhardwaj: Adapting, Assimilating and Culturalizing the Bard Koel Chatterjee PhD Thesis 10 October, 2017 I, Koel Chatterjee, hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly stated. Signed: Date: 10th October, 2017 Acknowledgements This thesis would not have been possible without the patience and guidance of my supervisor Dr Deana Rankin. Without her ability to keep me focused despite my never-ending projects and her continuous support during my many illnesses throughout these last five years, this thesis would still be a work in progress. I would also like to thank Dr. Ewan Fernie who inspired me to work on Shakespeare and Bollywood during my MA at Royal Holloway and Dr. Christie Carson who encouraged me to pursue a PhD after six years of being away from academia, as well as Poonam Trivedi, whose work on Filmi Shakespeares inspired my research. I thank Dr. Varsha Panjwani for mentoring me through the last three years, for the words of encouragement and support every time I doubted myself, and for the stimulating discussions that helped shape this thesis. Last but not the least, I thank my family: my grandfather Dr Somesh Chandra Bhattacharya, who made it possible for me to follow my dreams; my mother Manasi Chatterjee, who taught me to work harder when the going got tough; my sister, Payel Chatterjee, for forcing me to watch countless terrible Bollywood films; and my father, Bidyut Behari Chatterjee, whose impromptu recitations of Shakespeare to underline a thought or an emotion have led me inevitably to becoming a Shakespeare scholar. -

Raja Ravi Varma 145

viii PREFACE Preface i When Was Modernism ii PREFACE Preface iii When Was Modernism Essays on Contemporary Cultural Practice in India Geeta Kapur iv PREFACE Published by Tulika 35 A/1 (third floor), Shahpur Jat, New Delhi 110 049, India © Geeta Kapur First published in India (hardback) 2000 First reprint (paperback) 2001 Second reprint 2007 ISBN: 81-89487-24-8 Designed by Alpana Khare, typeset in Sabon and Univers Condensed at Tulika Print Communication Services, processed at Cirrus Repro, and printed at Pauls Press Preface v For Vivan vi PREFACE Preface vii Contents Preface ix Artists and ArtWork 1 Body as Gesture: Women Artists at Work 3 Elegy for an Unclaimed Beloved: Nasreen Mohamedi 1937–1990 61 Mid-Century Ironies: K.G. Subramanyan 87 Representational Dilemmas of a Nineteenth-Century Painter: Raja Ravi Varma 145 Film/Narratives 179 Articulating the Self in History: Ghatak’s Jukti Takko ar Gappo 181 Sovereign Subject: Ray’s Apu 201 Revelation and Doubt in Sant Tukaram and Devi 233 Frames of Reference 265 Detours from the Contemporary 267 National/Modern: Preliminaries 283 When Was Modernism in Indian Art? 297 New Internationalism 325 Globalization: Navigating the Void 339 Dismantled Norms: Apropos an Indian/Asian Avantgarde 365 List of Illustrations 415 Index 430 viii PREFACE Preface ix Preface The core of this book of essays was formed while I held a fellowship at the Nehru Memorial Museum and Library at Teen Murti, New Delhi. The project for the fellowship began with a set of essays on Indian cinema that marked a depar- ture in my own interpretative work on contemporary art. -

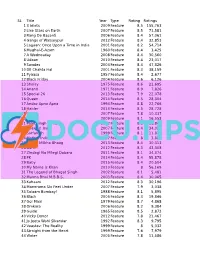

Aspirational Movie List

SL Title Year Type Rating Ratings 1 3 Idiots 2009 Feature 8.5 155,763 2 Like Stars on Earth 2007 Feature 8.5 71,581 3 Rang De Basanti 2006 Feature 8.4 57,061 4 Gangs of Wasseypur 2012 Feature 8.4 32,853 5 Lagaan: Once Upon a Time in India 2001 Feature 8.2 54,714 6 Mughal-E-Azam 1960 Feature 8.4 3,425 7 A Wednesday 2008 Feature 8.4 30,560 8 Udaan 2010 Feature 8.4 23,017 9 Swades 2004 Feature 8.4 47,326 10 Dil Chahta Hai 2001 Feature 8.3 38,159 11 Pyaasa 1957 Feature 8.4 2,677 12 Black Friday 2004 Feature 8.6 6,126 13 Sholay 1975 Feature 8.6 21,695 14 Anand 1971 Feature 8.9 7,826 15 Special 26 2013 Feature 7.9 22,078 16 Queen 2014 Feature 8.5 28,304 17 Andaz Apna Apna 1994 Feature 8.8 22,766 18 Haider 2014 Feature 8.5 28,728 19 Guru 2007 Feature 7.8 10,337 20 Dev D 2009 Feature 8.1 16,553 21 Paan Singh Tomar 2012 Feature 8.3 16,849 22 Chakde! India 2007 Feature 8.4 34,024 23 Sarfarosh 1999 Feature 8.1 11,870 24 Mother India 1957 Feature 8 3,882 25 Bhaag Milkha Bhaag 2013 Feature 8.4 30,313 26 Barfi! 2012 Feature 8.3 43,308 27 Zindagi Na Milegi Dobara 2011 Feature 8.1 34,374 28 PK 2014 Feature 8.4 55,878 29 Baby 2015 Feature 8.4 20,504 30 My Name Is Khan 2010 Feature 8 56,169 31 The Legend of Bhagat Singh 2002 Feature 8.1 5,481 32 Munna Bhai M.B.B.S.