Water Catchments of Lulunga District, Ha'apai, Tonga

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University of Auckland Research Repository, Researchspace

Libraries and Learning Services University of Auckland Research Repository, ResearchSpace Copyright Statement The digital copy of this thesis is protected by the Copyright Act 1994 (New Zealand). This thesis may be consulted by you, provided you comply with the provisions of the Act and the following conditions of use: • Any use you make of these documents or images must be for research or private study purposes only, and you may not make them available to any other person. • Authors control the copyright of their thesis. You will recognize the author's right to be identified as the author of this thesis, and due acknowledgement will be made to the author where appropriate. • You will obtain the author's permission before publishing any material from their thesis. General copyright and disclaimer In addition to the above conditions, authors give their consent for the digital copy of their work to be used subject to the conditions specified on the Library Thesis Consent Form and Deposit Licence. Sauerkraut and Salt Water: The German-Tongan Diaspora Since 1932 Kasia Renae Cook A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in German, the University of Auckland, 2017. Abstract This is a study of individuals of German-Tongan descent living around the world. Taking as its starting point the period where Germans in Tonga (2014) left off, it examines the family histories, self-conceptions of identity, and connectedness to Germany of twenty-seven individuals living in New Zealand, the United States, Europe, and Tonga, who all have German- Tongan ancestry. -

Christianity and Taufa'āhau in Tonga

Melanesian Journal of Theology 23-1 (2007) CHRISTIANITY AND TAUFA‘ĀHAU IN TONGA: 1800-1850 Finau Pila ‘Ahio Revd Dr Finau Pila ‘Ahio serves as Principal of the Sia‘atoutai Theological College in Tonga. INTRODUCTION Near the centre of the Pacific Ocean lies the only island kingdom in the region, and the smallest in the world, Tonga. It is a group of small islands, numbering about 150, with only 36 of them inhabited, and which are scattered between 15º and 23º south latitude, and between 173º and 177º west longitude. The kingdom is divided into three main island groups: Tongatapu, situated to the south, Ha‘apai, an extensive archipelago of small islands in the centre, and Vava‘u, in the north. Tonga lies 1,100 miles northeast of New Zealand, and 420 miles southeast of Fiji. With a total area of 269 square miles, the population is more than 100,000, most of whom are native Polynesians. Tonga is an agricultural country, and most of the inhabited islands are fertile. The climate, however, is semi-tropical, with heavy rainfall and high humidity. Tonga, along with the rest of the Pacific, was completely unknown to Europe until the exploration of the area by the Spaniards and Portuguese during the 16th century. These explorers were seeking land to establish colonies, and to convert the inhabitants to Christianity. By the second decade of the 17th century, more explorers from other parts of Europe came into the area, to discover an unknown southern continent called “Terra Australis Incognita”, between South America and Africa. Among these, the Dutch were the first Europeans to discover Tonga. -

Tropical Cyclone Ian

Information Bulletin Tonga: Tropical Cyclone Ian Information Bulletin n°1 GLIDE n° 2014-000003 14 January 2014 This bulletin is being issued for information only and reflects the current situation and details available at this time. The International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC) is not seeking funding or other assistance from donors for this operation. <click here for detailed contact information> Damage to homes on Lifuka Island, Ha'apai, Tonga. Photo credit: NZ Air Force (taken from http://ocha.smugmug.com/) The situation Severe Tropical Cyclone (TC) Ian formed in the northwest of Tonga and southeast of Fiji waters on 6 January. TC Ian tracked southeast towards the Tongan Island groups of Vava’u (population 15,000) and Ha’apai (population 60161) intensifying to Category 5, with wind speeds of more than 270 mph, before turning on a more southerly track. Tonga Red Cross Society (TRCS) alerted trained emergency response team (ERT) responders to stand by on 6 January 2014. After passing through the Vava’u group TC Ian passed directly over Foa, Lifuka, Kauvai (Ha’ano) and 'Uiha in the Ha’apai group of islands on Saturday, 11 January. Some of the islands within the affected area are low lying and susceptible to sea level rises and storm surge. Storm surges in Kavai (Ha’ano) that accompanied the event were estimated to be around 4-5 metres at their peak. A state of emergency was declared for the divisions of Vava’u and Ha’apai on Saturday morning 11 January. So far only minor damages have been reported in Vava’u. -

1 1 INTRODUCTION the Government of the Kingdom of Tonga

1 INTRODUCTION The Government of the Kingdom of Tonga has formally proposed the designation of the entire Ha'apai Group, the 62 central islands of Tonga (see maps below), as a Conservation Area (CA) under the South Pacific Regional Environment Programme (SPREP)'s South Pacific Biodiversity Conservation Programme (SPBCP). The proposal to SPBCP for the funding of a "Ha'apai Conservation Area Project" (HCAP) has been subsequently approved by SPBCP as Tonga's project under SPBCP, subject to the completion of a detailed Project Preparation Document (PPD) by the Kingdom of Tonga. This document constitutes the PPD for the Ha'apai Conservation Area Project. The main objectives of this Project Preparation Document are to: 1. Provide relevant background information on the proposed Ha'apai Conservation Area (HCA); 2. Draw attention to issues of concern relevant to biodiversity conservation within the HCA; 3. Identify desirable objectives, activities, strategies and an organisational or management structure of the HCAP; and, 4. Provide a detailed Work Plan of activities for the implementation of the HCAP under Phase 1 (the first year) of the HCAP. For the preparation of this PPD a mission was undertaken to Tongatapu and Ha'apai in January 1995 by SPREP/SPBCP consultants, Dr. Randy Thaman and Mr. Robert Gillett, officials from the Land and Environmental Planning Unit (LEPU) of the Ministry of Lands, Survey and Natural Resources (MLSNR), and data collection staff. The objectives of the PPD mission were: 1. To determine the degree of community interest in and willingness to become active participants in the Project; 2. To identify, using a participatory approach, the major issues of concern or constraints to, and activities that might promote, biodiversity conservation and sustainable development; 3. -

Information to Users

The political ecology of a Tongan village Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Stevens, Charles John, 1950- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 09/10/2021 00:11:56 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/290684 INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly fi-om the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter &ce, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper lefr-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. -

Environmental Assessment TONGA: Climate Resilience Sector Project

Environmental Assessment INITIAL ENVIRONMENTAL EXAMINATION Project No. 46351 November 2016 TONGA: Climate Resilience Sector Project Ha’apai Hospital Relocation and Construction Subproject Prepared by the Ministry of Meteorology, Energy, Information, Disaster Management, Environment, Climate Change and Communications and the Ministry of Finance for the Asian Development Bank This initial environmental examination is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. Initial Environmental Examination (IEE) Ha’apai Hospital Relocation and Construction Project Niu’ui Lifuka Island, Ha’apai Island, Kingdom of Tonga Prepared by PMU Climate Resilient Sector Project (CRSP) For Ministry of Meteorology, Energy, Information, Disaster Management, Environment, Climate Change and Communications (MEIDECC) Project Number: ADB Grant 378 - TON November 2016 1 NOTES In this report, "$" refers to US dollars unless otherwise stated. This initial environmental examination is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. -

Cyclone Ian Recovery Project

Environmental Assessment Report Project Number: 48192 June 2014 Tonga: Cyclone Ian Recovery Project Initial Environmental Examination – Disaster Relief Funding - School Reconstruction Projects The initial environmental examination report is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of the ADB’s Board of Directors, management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. Project 48192: Cyclone Ian Recovery Project Contents Acronyms and Abbreviations ........................................................................................................ 10 Executive Summary ...................................................................................................................... 11 Introduction and Background ........................................................................................................ 12 Description of Projects .................................................................................................................. 16 Lifuka Government Primary Schools ......................................................................................... 19 Koulo Government Primary School ........................................................................................... -

Initial Environmental Examination Document Stage: Draft Project Number: 48192-001 January 2015

Environmental Assessment Report Initial Environmental Examination Document Stage: Draft Project Number: 48192-001 January 2015 Kingdom of Tonga: Cyclone Ian Recovery Project – Component 1 (Energy Sector) Prepared by the Tonga Power Ltd for the Asian Development Bank This initial environmental examination is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 23 January 2015) Currency Unit = Tonga: pa'anga (TOP) TOP1.00 = US$ 0.48 US$1.00 = TOP 1.79 LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS ADB - Asian Development Bank CFC - Chlorofluorocarbons DG - Diesel Generator EA - Executing Agency EIA - Environmental Impact Assessment EMP - Environmental Management Plan EPC - Engineering, Procurement and Construction GoT - Government of Tonga GDP - Gross Domestic Product GFP - Grievance Focal Points GHG - Green House Gases GRC - Grievance Redress Committee GFP - Grievance Focal Point IA - Implementing Agency IEC - Island Electricity Committee IEE - Initial Environmental Examination IUCN - International Union for Conservation of Nature MFNP - Ministry of Finance and National Planning MLECCNR - Ministry of Lands, Environment, Climate Change and Natural Resources PCBs - polychlorinated biphenyl PMC - Project Management Consultant PPTA - Project Preparatory Technical Assistance REA - Rapid Environmental Assessment SHS - Solar Home System SPS - Safeguard Policy Statement TA - Technical Assistance TERM - Tonga Energy Road Map TERM - IU - Tonga Energy Road Map – Implementing Unit TPL - Tonga Power Limited T&D - Transmission & Distribution NOTES (i) The fiscal year (FY) of the Government of Tonga ends on 31 December. -

Kolo Velata: an Analysis of West Polynesian Fortifications

KOLO VELATA: AN ANALYSIS OF WEST POLYNESIAN FORTIFICATIONS by Anthony P. Marais B.A., University of California, Berkeley, 1990 THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of Archaeology O Anthony P. Marais 1995 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY May 1995 All rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. APPROVAL Name: Anthony P. Marais Degree: Master of Arts Title of Thesis: Kolo Velata: An Analysis of West Polynesian Fortifications Examining Committee: Chair: Jack Nancc David V. Burley Senior Supervisor Richard Shutler. Jr .- Douglas Sutton Extcrnal Examiner Department of Anthropology University of Auckland PARTIAL COPYRIGHT LICENSE I hereby grant to Simon Fraser University the right to lend my thesis, project or extended essay (the title of which is shown below) to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. I further agree that permission for multiple copying of this work for scholarly purposes may be granted by me or the Dean of Graduate Studies. It is understood that copying or publication of this work for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Title of Thesis/Project/Extended Essay Kolo Velata: An Analysis of West Polynesian Fortifications Author: (signature) Anthony P. Marais (name) May 31, 1995 (date) ABSTRACT For some time ring-ditch fortifications in Tonga have been the focus of archaeological interest. -

Groundwater Resources Assessment

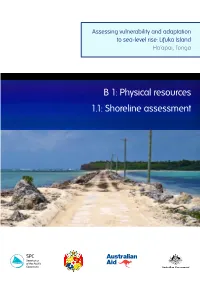

Assessing vulnerability and adaptation to sea-level rise: Lifuka Island Ha’apai, Tonga B 1: Physical resources 1.1: Shoreline assessment CONTACT DETAILS Secretariat of the Pacific Community SPC Headquarters SPC Suva Regional Office SPC Pohnpei Regional Office SPC Solomon Islands BP D5, Private Mail Bag, PO Box Q, Country Office 98848 Noumea Cedex, Suva, Kolonia, Pohnpei, 96941 FM, PO Box 1468 New Caledonia Fiji, Federated States of Honiara, Solomon Islands Telephone: +687 26 20 00 Telephone: +679 337 0733 Micronesia Telephone: + 677 25543 Fax: +687 26 38 18 Fax: +679 337 0021 Telephone: +691 3207 523 +677 25574 Fax: +691 3202 725 Fax: +677 25547 Email: [email protected] Website: www.spc.int Assessing vulnerability and adaptation to sea-level rise: Lifuka Island Ha’apai, Tonga B 1: Physical resources 1.2: Groundwater resources assessment Peter Sinclair, Amit Singh, Quddus Fielea, Kate Hyland, A‘pai Moala Secretariat of the Pacific Community Suva, Fiji 2014 © Copyright Secretariat of the Pacific Community 2014 All rights for commercial / for profit reproduction or translation, in any form, reserved. SPC authorises the partial reproduction or translation of this material for scientific, educational or research purposes, provided that SPC and the source document are properly acknowledged. Permission to reproduce the document and/ or translate in whole, in any form, whether for commercial / for profit or non-profit purposes, must be requested in writing. Original SPC artwork may not be altered or separately published without permission. Original text: English Secretariat of the Pacific Community Cataloguing-in-publication data Sinclair, Peter J. B 1: Physical resources 1.2: Groundwater resources assessment / Peter Sinclair, Amit Singh, Quddus Fielea, Kate Hyland, A‘pai Moala (Assessing vulnerability and adaptation to sea-level rise: Lifuka Island, Ha’apai, Tonga / Secretariat of the Pacific Community) 1. -

Tonga Outer Islands Renewable Energy

Initial Environmental Examination May 2012 Kingdom of Tonga: Outer Island Renewable Energy Project – Phase 1 (200 KWp ‘Eua Solar Power Plant) Prepared by Tonga Power Limited (TPL), Government of Tonga for the Asian Development Bank. This initial environmental examination is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 31 March 2012) Currency Unit = Tonga: pa'anga (TOP) TOP1.00 = US$ 0.59 US$1.00 = TOP 1.67 LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS ADB - Asian Development Bank CFC - Chlorofluorocarbons EA - Executing Agency EIA - Environmental Impact Assessment EMP - Environmental Management Plan GoT - Government of Tonga GFP - Grievance Focal Points GHG - Green House Gases GRC - Grievance Redress Commission IA - Implementing Agency IEE - Initial Environmental Examination MECC - Ministry of Environment and Climate Change PCBs - polychlorinated biphenyl REA - Rapid Environmental Assessment SPS - Safeguard Policy Statement TA - Technical Assistance TERM - Tonga Energy Road Map TPL - Tonga Power Limited NOTES (i) The fiscal year (FY) of the Government of Tonga ends on 31 December. FY before a calendar year denotes the year in which the fiscal year ends, e.g., FY2011 ends on 31 December 2011. (ii) In this report, "$" refers to US dollars 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page A. -

Status of Land Birds on Selected Islands in the Ha'apai Group, Kingdom of Tonga1

Pacific Science (1998), vol. 52, no. 1: 14-34 © 1998 by University of Hawai'i Press. All rights reserved Status of Land Birds on Selected Islands in the Ha'apai Group, Kingdom of Tonga1 DAVID W. STEADMAN2 ABSTRACT: Based on fieldwork in 1995 and 1996, I assess the distribution, relative abundance, and habitat requirements of indigenous species of land birds on 13 islands in the Ha'apai Group, Kingdom of Tonga. Among the 2 islands visited, primary forest still exists only on the large (46.6 km ), hi~h (558 m) volcanic island ofTofua. Vegetation on the 12 smaller (0.15-13.3 km ), lower (6-45 m) islands is dominated by a mosaic of active and abandoned agricultural plots, nearly all with an overstory of coconut trees. Because of cultivation practices, very little of this vegetation is reverting to secondary forest. Ofthe 15 resident species ofland birds that survive on these islands, nine are widespread and at least locally common within Ha'apai, although only four (Gallirallus philippensis, Ptilinopus porphyraceus, Halcyon chloris, Aplonis ta buensis) certainly or probably occur nowadays on all 13 islands. Three species (Gallicolumba stairii, Ptilinopus perousii, Clytorhynchus vitiensis) are extirpated or extremely rare on all islands surveyed except Tofua. Overall species richness and abundance of land birds are much greater on Tofua than on the other islands. This difference may be due more to the presence of primary forest on Tofua than to Tofua's greater area and elevation. Tms PAPER DESCRIBES the current status of (Watling 1982, Steadman 1993, 1997b). The native land birds on 13 islands in the Ha'apai extant, indigenous land birds of Tonga rep Group, Kingdom of Tonga.