Cripping the Apocalypse Some of My Wild Disability Justice Dreams

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Analysis of Hegemonic Social Structures in "Friends"

"I'LL BE THERE FOR YOU" IF YOU ARE JUST LIKE ME: AN ANALYSIS OF HEGEMONIC SOCIAL STRUCTURES IN "FRIENDS" Lisa Marie Marshall A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY August 2007 Committee: Katherine A. Bradshaw, Advisor Audrey E. Ellenwood Graduate Faculty Representative James C. Foust Lynda Dee Dixon © 2007 Lisa Marshall All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Katherine A. Bradshaw, Advisor The purpose of this dissertation is to analyze the dominant ideologies and hegemonic social constructs the television series Friends communicates in regard to friendship practices, gender roles, racial representations, and social class in order to suggest relationships between the series and social patterns in the broader culture. This dissertation describes the importance of studying television content and its relationship to media culture and social influence. The analysis included a quantitative content analysis of friendship maintenance, and a qualitative textual analysis of alternative families, gender, race, and class representations. The analysis found the characters displayed actions of selectivity, only accepting a small group of friends in their social circle based on friendship, gender, race, and social class distinctions as the six characters formed a culture that no one else was allowed to enter. iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This project stems from countless years of watching and appreciating television. When I was in college, a good friend told me about a series that featured six young people who discussed their lives over countless cups of coffee. Even though the series was in its seventh year at the time, I did not start to watch the show until that season. -

Summer Classic Film Series, Now in Its 43Rd Year

Austin has changed a lot over the past decade, but one tradition you can always count on is the Paramount Summer Classic Film Series, now in its 43rd year. We are presenting more than 110 films this summer, so look forward to more well-preserved film prints and dazzling digital restorations, romance and laughs and thrills and more. Escape the unbearable heat (another Austin tradition that isn’t going anywhere) and join us for a three-month-long celebration of the movies! Films screening at SUMMER CLASSIC FILM SERIES the Paramount will be marked with a , while films screening at Stateside will be marked with an . Presented by: A Weekend to Remember – Thurs, May 24 – Sun, May 27 We’re DEFINITELY Not in Kansas Anymore – Sun, June 3 We get the summer started with a weekend of characters and performers you’ll never forget These characters are stepping very far outside their comfort zones OPENING NIGHT FILM! Peter Sellers turns in not one but three incomparably Back to the Future 50TH ANNIVERSARY! hilarious performances, and director Stanley Kubrick Casablanca delivers pitch-dark comedy in this riotous satire of (1985, 116min/color, 35mm) Michael J. Fox, Planet of the Apes (1942, 102min/b&w, 35mm) Humphrey Bogart, Cold War paranoia that suggests we shouldn’t be as Christopher Lloyd, Lea Thompson, and Crispin (1968, 112min/color, 35mm) Charlton Heston, Ingrid Bergman, Paul Henreid, Claude Rains, Conrad worried about the bomb as we are about the inept Glover . Directed by Robert Zemeckis . Time travel- Roddy McDowell, and Kim Hunter. Directed by Veidt, Sydney Greenstreet, and Peter Lorre. -

The Intertwining of Multimedia in Emma, Clueless, and Gossip Girl Nichole Decker Honors Scholar Project May 6, 2019

Masthead Logo Scholar Works Honors Theses Honors 2019 Bricolage on the Upper East Side: The nI tertwining of Multimedia in Emma, Clueless, and Gossip Girl Nichole Decker University of Maine at Farmington Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umf.maine.edu/honors_theses Part of the Comparative Literature Commons Recommended Citation Decker, Nichole, "Bricolage on the Upper East Side: The nI tertwining of Multimedia in Emma, Clueless, and Gossip Girl" (2019). Honors Theses. 5. https://scholarworks.umf.maine.edu/honors_theses/5 This Research Project is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors at Scholar Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholar Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 2 Bricolage on the Upper East Side: The Intertwining of Multimedia in Emma, Clueless, and Gossip Girl Nichole Decker Honors Scholar Project May 6, 2019 “Okay, so you’re probably going, is this like a Noxzema commercial or what?” - Cher In this paper I will analyze the classic novel Emma, and the 1995 film Clueless, as an adaptive pair, but I will also be analyzing the TV series, Gossip Girl, as a derivative text. I bring this series into the discussion because of the ways in which it echos, parallels, and alludes to both Emma and Clueless individually, and the two as a source pair. I do not argue that the series is an actual adaptation, but rather, a sort of collage, recombining motifs from both source texts to create something new, exciting, and completely absurd. -

A Character Analysis in Jane Austen's Emma and Amy Heckerling's Clueless Through Intertextuality

SOCIAL MENTALITY AND RESEARCHER THINKERS JOURNAL Doı: http://dx.doi.org/10.31576/smryj.580 REVIEW ARTICLE SmartJournal 2020; 6(34):1286-1297 Arrival : 23/06/2020 Published : 20/08/2020 A CHARACTER ANALYSIS IN JANE AUSTEN’S EMMA AND AMY HECKERLING’S CLUELESS THROUGH INTERTEXTUALITY Jane Austen'nin Emma Ve Amy Heckerlıng'in Clueless’ında Metinlerarasılık Bağlamında Karakter Analizi Reference: Albay, N.G. (2020). “A Character Analysıs In Jane Austen’s Emma And Amy Heckerlıng’s Clueless Through Intertextualıty”, International Social Mentality and Researcher Thinkers Journal, (Issn:2630-631X) 6(34): 1286-1297. English Instructor, Dr Neslihan G. ALBAY Istanbul Sabahattin Zaim University, Foreign Languages Coordination, English Preparatory School, Istanbul / Turkey ABSTRACT ÖZET Based on the interaction between cinema and classical Sinema ve klasik eserler arasındaki etkileşime dayanarak, works, Jane Austen’s Emma and Amy Heckerling’s Clueless Jane Austen’in Emma ve Amy Heckerling’in Clueless adlı enable us to make an intriguing character analysis through eseri, yirminci yüzyılın merceğinden ilginç bir karakter the lens of the twentieth century. In her novels, Austen analizi yapmamızı sağlıyor. Austen romanlarında arazi embraced the themes of love and marriage in a society mülkiyeti, gelir ve sosyal statünün hakim olduğu bir dominated by land ownership, income and social status. She toplumda sevgi ve evlilik temalarını benimsemiştir. 19. dealt with the conflicts and problems arising from the yüzyılda yaşayan burjuvazinin ve orta sınıfın evlilik marriage issues of the bourgeoisie and middle class living in sorunlarından kaynaklanan çatışma ve sorunları ele the 19th century. Like many women writers she was almıştır. Birçok kadın yazar gibi eleştirildi, eserleri bu criticized, her works were not recognized or published sorunlar nedeniyle tanınmadı veya yayınlanmadı. -

Reporters Without Borders On-Express-02-07-2014,46574.Html

Reporters Without Borders http://www.rsf.org/pakistan-another-bomb-attack- on-express-02-07-2014,46574.html Asia - Pakistan Targeted yet again Another bomb attack on Express News TV’s Peshawar bureau chief 2 July 2014 The latest in a nearly year-old string of attacks on Express News personnel and installations Reporters Without Borders condemns today’s bombing of the home of Jamshed Baghwan, Express News TV’s bureau chief in Peshawar. It was the third attempt to target Baghwan and his family with an explosive device since March and the latest in an 11-month-old string of attacks on Express Media group personnel and installations, some of which have been claimed by the Taliban. Left in a milk pack in front of the house by men on a motorcycle, today’s home-made bomb damaged the outside of the building but caused no injuries when it was set off by a timer at 11 am. “We are outraged by this latest murder attempt targeting an Express News journalist and his family,” said Benjamin Ismaïl, the head of the Reporters Without Borders Asia-Pacific desk. “We urge the authorities to react quickly and to assign security personnel to protect their home.” “My family members and I are all safe, thank God,” Baghwan told RWB. “More than one kilogram of explosives was used in the attack. Today’s blast was bigger than the previous ones.” Asked who he thought was behind the bombs, Baghwan said: “The enemy is unknown. I am clueless as to why these elements are targeting my house. -

A FAILURE of INITIATIVE Final Report of the Select Bipartisan Committee to Investigate the Preparation for and Response to Hurricane Katrina

A FAILURE OF INITIATIVE Final Report of the Select Bipartisan Committee to Investigate the Preparation for and Response to Hurricane Katrina U.S. House of Representatives 4 A FAILURE OF INITIATIVE A FAILURE OF INITIATIVE Final Report of the Select Bipartisan Committee to Investigate the Preparation for and Response to Hurricane Katrina Union Calendar No. 00 109th Congress Report 2nd Session 000-000 A FAILURE OF INITIATIVE Final Report of the Select Bipartisan Committee to Investigate the Preparation for and Response to Hurricane Katrina Report by the Select Bipartisan Committee to Investigate the Preparation for and Response to Hurricane Katrina Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.gpoacess.gov/congress/index.html February 15, 2006. — Committed to the Committee of the Whole House on the State of the Union and ordered to be printed U. S. GOVERNMEN T PRINTING OFFICE Keeping America Informed I www.gpo.gov WASHINGTON 2 0 0 6 23950 PDF For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512-1800; DC area (202) 512-1800 Fax: (202) 512-2250 Mail: Stop SSOP, Washington, DC 20402-0001 COVER PHOTO: FEMA, BACKGROUND PHOTO: NASA SELECT BIPARTISAN COMMITTEE TO INVESTIGATE THE PREPARATION FOR AND RESPONSE TO HURRICANE KATRINA TOM DAVIS, (VA) Chairman HAROLD ROGERS (KY) CHRISTOPHER SHAYS (CT) HENRY BONILLA (TX) STEVE BUYER (IN) SUE MYRICK (NC) MAC THORNBERRY (TX) KAY GRANGER (TX) CHARLES W. “CHIP” PICKERING (MS) BILL SHUSTER (PA) JEFF MILLER (FL) Members who participated at the invitation of the Select Committee CHARLIE MELANCON (LA) GENE TAYLOR (MS) WILLIAM J. -

WITH OUR DEMONS a Thesis Submitted By

1 MONSTROSITIES MADE IN THE INTERFACE: THE IDEOLOGICAL RAMIFICATIONS OF ‘PLAYING’ WITH OUR DEMONS A Thesis submitted by Jesse J Warren, BLM Student ID: u1060927 For the award of Master of Arts (Humanities and Communication) 2020 Thesis Certification Page This thesis is entirely the work of Jesse Warren except where otherwise acknowledged. This work is original and has not previously been submitted for any other award, except where acknowledged. Signed by the candidate: __________________________________________________________________ Principal Supervisor: _________________________________________________________________ Abstract Using procedural rhetoric to critique the role of the monster in survival horror video games, this dissertation will discuss the potential for such monsters to embody ideological antagonism in the ‘game’ world which is symptomatic of the desire to simulate the ideological antagonism existing in the ‘real’ world. Survival video games explore ideology by offering a space in which to fantasise about society's fears and desires in which the sum of all fears and object of greatest desire (the monster) is so terrifying as it embodies everything 'other' than acceptable, enculturated social and political behaviour. Video games rely on ideology to create believable game worlds as well as simulate believable behaviours, and in the case of survival horror video games, to simulate fear. This dissertation will critique how the games Alien:Isolation, Until Dawn, and The Walking Dead Season 1 construct and themselves critique representations of the ‘real’ world, specifically the way these games position the player to see the monster as an embodiment of everything wrong and evil in life - everything 'other' than an ideal, peaceful existence, and challenge the player to recognise that the very actions required to combat or survive this force potentially serve as both extensions of existing cultural ideology and harbingers of ideological resistance across two worlds – the ‘real’ and the ‘game’. -

Healthy Street Pilot Projects

ANN ARBOR HEALTHY STREET PILOT PROJECTS Summary of Findings January 14, 2021 Prepared by SmithGroup 1 HEALTHY STREET PILOT PROJECTS City Council passed R-20-158 “Resolution to Promote Safe Social Distancing Outdoors in Ann Arbor” on May 4, 2020. This resolution directed staff to (among other things) “develop recommendations and implementation strategies on comprehensive lane or street re-configurations (and report as soon as possible concerning these recommendations and strategies), including the possible cost of such options, the research conducted, and public input received, and other relevant data.” In response to this directive, City and Downtown Development Authority (DDA) staff gave a presentation on recommendations on June 15, 2020 along with two accompanying resolutions: “Resolution to Advance Healthy Streets in Downtown” and “Resolution to Advance Healthy Streets Outside Downtown.” These resolutions were passed by City Council on July 6, 2020. On August 27th the Ann Arbor DDA and the City of Ann Arbor began installing a series of healthy street pilot projects in the downtown area to provide space for safe physical distancing for bicycle and pedestrian travel. These projects, with the approval of City Council, reconfigured traffic lanes to accommodate temporary pedestrian and bicycle facilities, such as non-motorized travel lanes, two-way bikeways, and separated bike lanes. The pilot projects discussed in this report include the following locations: • Miller/Catherine Bikeway (from 1st Street to Division) • Division Street/Broadway Bikeway (from Packard to Maiden Lane) • S. Main Separated Bike Lanes (from William to Stadium) • State & North University Bikeway (from William Street to Thayer) • Packard Bike Lanes (from State to Hill) • East Packard Project (from Platt to Eisenhower) The pilot projects were designed and implemented in alignment with national guidance, City policies and plans, and the DDA’s adopted values for the People-Friendly Streets program. -

A Sense of Unending: Apocalypse and Post-Apocalypse in Novels of Late Capitalism" (2019)

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville ScholarWorks@UARK Theses and Dissertations 8-2019 A Sense of Unending: Apocalypse and Post- Apocalypse in Novels of Late Capitalism Brent Linsley University of Arkansas, Fayetteville Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd Part of the American Literature Commons, Literature in English, North America Commons, and the Modern Literature Commons Recommended Citation Linsley, Brent, "A Sense of Unending: Apocalypse and Post-Apocalypse in Novels of Late Capitalism" (2019). Theses and Dissertations. 3341. https://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/3341 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Sense of Unending: Apocalypse and Post-Apocalypse in Novels of Late Capitalism A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English by Brent Linsley Henderson State University Bachelor of Arts in English, 2000 Henderson State University Master of Liberal Arts in English, 2005 August 2019 University of Arkansas This dissertation is approved for recommendation to the Graduate Council. _____________________________________ M. Keith Booker, Ph.D. Dissertation Director _____________________________________ ______________________________________ Robert Cochran, Ph.D. Susan Marren, Ph.D. Committee Member Committee Member Abstract From Frank Kermode to Norman Cohn to John Hall, scholars agree that apocalypse historically has represented times of radical change to social and political systems as older orders are wiped away and replaced by a realignment of respective norms. This paradigm is predicated upon an understanding of apocalypse that emphasizes the rebuilding of communities after catastrophe has occurred. -

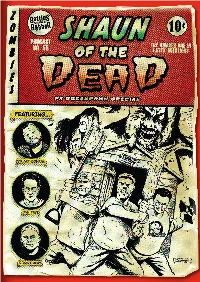

Battleswithbitsofrubber.Com Page 1 CONTENTS

battleswithbitsofrubber.com Page 1 CONTENTS Credits and thanks....................................................................................... Page 3 Foreword by Joe Nazzaro ........................................................................... Page 4 Introduction ................................................................................................. Page 5 Effects in chronological order 1. ‘Haven’t you had your tea?’ ................................................................... Page 6 2. ‘In the garden ... there’s a girl’................................................................ Page 7 3. ‘He’s got an arm off...’ ............................................................................. Page 9 4. ‘Which one do you want? Girl or bloke?’ ........................................... Page 11 5. ‘We take care of Philip.’ .......................................................................... Page 13 6. ‘We’re gonna borrow your car, okay...’ ................................................ Page 13 7. ‘I guess we’ll have to take the Jag.’ ...................................................... Page 14 8. ‘I’ll just flip the mains breakers...’ ........................................................ Page 15 9. ‘I didn’t want to say anything.’.............................................................. Page 16 10. ‘Cock it!’.................................................................................................. Page 17 11. ‘I’m sorry Mum.’ ..................................................................................... -

A Feminist Criticism of House

Lutzker 1 House is a medical drama based on the fictitious story of Dr . Gregory House, a cruelly sarcastic, yet brilliant, doctor . Dr . House works as a diagnostician at the Princeton-Plainsboro Hospital where he employs a team of young doctors who aspire to achieve greater success in their careers . Being a member of House’s team is a privilege, yet the team members must be able to tolerate Dr . House’s caustic sense of humor . Because of Dr . House’s brilliance, his coworkers and bosses alike tend to overlook his deviant and childish behaviors . Even though Dr . House’s leg causes him to be in severe pain every day, and has contributed to his negative outlook on life, both his patients and coworkers do not have much sympathy for him . The main goals of House’s outlandish behaviors are to solve the puzzle of his patients’ medical cases . Dr . House handpicks the patients whom he finds have interesting medical quandaries and attempts to diagnose them . By conferring with his team, and “asking” for permission from Dr . Lisa Cuddy, Dr . House is able to treat the patients as he sees fit . He usually does not diagnose the patients correctly the first time . However, with each new symptom, a new piece of the puzzle unfolds, giving a clearer view of the cause of illness . Dr . House typically manages to save the lives of his patients by the end of the episode, usually without having any physical contact with the patient . Dr . House has an arrogant and self-righteous personality . Some of the lines that are written for Dr . -

GLAAD Where We Are on TV (2020-2021)

WHERE WE ARE ON TV 2020 – 2021 WHERE WE ARE ON TV 2020 – 2021 Where We Are on TV 2020 – 2021 2 WHERE WE ARE ON TV 2020 – 2021 CONTENTS 4 From the office of Sarah Kate Ellis 7 Methodology 8 Executive Summary 10 Summary of Broadcast Findings 14 Summary of Cable Findings 17 Summary of Streaming Findings 20 Gender Representation 22 Race & Ethnicity 24 Representation of Black Characters 26 Representation of Latinx Characters 28 Representation of Asian-Pacific Islander Characters 30 Representation of Characters With Disabilities 32 Representation of Bisexual+ Characters 34 Representation of Transgender Characters 37 Representation in Alternative Programming 38 Representation in Spanish-Language Programming 40 Representation on Daytime, Kids and Family 41 Representation on Other SVOD Streaming Services 43 Glossary of Terms 44 About GLAAD 45 Acknowledgements 3 WHERE WE ARE ON TV 2020 – 2021 From the Office of the President & CEO, Sarah Kate Ellis For 25 years, GLAAD has tracked the presence of lesbian, of our work every day. GLAAD and Proctor & Gamble gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) characters released the results of the first LGBTQ Inclusion in on television. This year marks the sixteenth study since Advertising and Media survey last summer. Our findings expanding that focus into what is now our Where We Are prove that seeing LGBTQ characters in media drives on TV (WWATV) report. Much has changed for the LGBTQ greater acceptance of the community, respondents who community in that time, when our first edition counted only had been exposed to LGBTQ images in media within 12 series regular LGBTQ characters across both broadcast the previous three months reported significantly higher and cable, a small fraction of what that number is today.