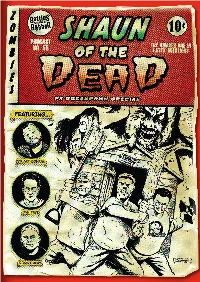

The Zombies Are Coming Comp Copy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs No. Interpret Title Year of release 1. Bob Dylan Like a Rolling Stone 1961 2. The Rolling Stones Satisfaction 1965 3. John Lennon Imagine 1971 4. Marvin Gaye What’s Going on 1971 5. Aretha Franklin Respect 1967 6. The Beach Boys Good Vibrations 1966 7. Chuck Berry Johnny B. Goode 1958 8. The Beatles Hey Jude 1968 9. Nirvana Smells Like Teen Spirit 1991 10. Ray Charles What'd I Say (part 1&2) 1959 11. The Who My Generation 1965 12. Sam Cooke A Change is Gonna Come 1964 13. The Beatles Yesterday 1965 14. Bob Dylan Blowin' in the Wind 1963 15. The Clash London Calling 1980 16. The Beatles I Want zo Hold Your Hand 1963 17. Jimmy Hendrix Purple Haze 1967 18. Chuck Berry Maybellene 1955 19. Elvis Presley Hound Dog 1956 20. The Beatles Let It Be 1970 21. Bruce Springsteen Born to Run 1975 22. The Ronettes Be My Baby 1963 23. The Beatles In my Life 1965 24. The Impressions People Get Ready 1965 25. The Beach Boys God Only Knows 1966 26. The Beatles A day in a life 1967 27. Derek and the Dominos Layla 1970 28. Otis Redding Sitting on the Dock of the Bay 1968 29. The Beatles Help 1965 30. Johnny Cash I Walk the Line 1956 31. Led Zeppelin Stairway to Heaven 1971 32. The Rolling Stones Sympathy for the Devil 1968 33. Tina Turner River Deep - Mountain High 1966 34. The Righteous Brothers You've Lost that Lovin' Feelin' 1964 35. -

Summer Classic Film Series, Now in Its 43Rd Year

Austin has changed a lot over the past decade, but one tradition you can always count on is the Paramount Summer Classic Film Series, now in its 43rd year. We are presenting more than 110 films this summer, so look forward to more well-preserved film prints and dazzling digital restorations, romance and laughs and thrills and more. Escape the unbearable heat (another Austin tradition that isn’t going anywhere) and join us for a three-month-long celebration of the movies! Films screening at SUMMER CLASSIC FILM SERIES the Paramount will be marked with a , while films screening at Stateside will be marked with an . Presented by: A Weekend to Remember – Thurs, May 24 – Sun, May 27 We’re DEFINITELY Not in Kansas Anymore – Sun, June 3 We get the summer started with a weekend of characters and performers you’ll never forget These characters are stepping very far outside their comfort zones OPENING NIGHT FILM! Peter Sellers turns in not one but three incomparably Back to the Future 50TH ANNIVERSARY! hilarious performances, and director Stanley Kubrick Casablanca delivers pitch-dark comedy in this riotous satire of (1985, 116min/color, 35mm) Michael J. Fox, Planet of the Apes (1942, 102min/b&w, 35mm) Humphrey Bogart, Cold War paranoia that suggests we shouldn’t be as Christopher Lloyd, Lea Thompson, and Crispin (1968, 112min/color, 35mm) Charlton Heston, Ingrid Bergman, Paul Henreid, Claude Rains, Conrad worried about the bomb as we are about the inept Glover . Directed by Robert Zemeckis . Time travel- Roddy McDowell, and Kim Hunter. Directed by Veidt, Sydney Greenstreet, and Peter Lorre. -

Rocking the Digital & Physical World

ROCKING THE DIGITAL & PHYSICAL WORLD When you can’t welcome fans to the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame, you take the Rock & Roll DAWN WAYT Hall of Fame to the fans. Learn how the Rock VP of Marketing & Sales Hall pivoted during the pandemic to connect people of all backgrounds and beliefs to the July 28, 2020 music we love through engaging content, exhibits, and experiences that make life just a little bit better. 2020: Pandemic, protest & Pivot • 2019 ROCKED • 2020 ON A ROLL • 2020 WTF JUST HAPPENED • 2020 WE GOT THIS 3 2019 rocked 4 2019 rocked McDANIELS of Run DMC 2019 rocked GEORGE CLINTON THE ZOMBIES of Parliament Funkadelic 2019 rocked MAVIS STAPLES JACKSON BROWNE of the Staple Singers 2019 rocked ROBERT TRUJILLO of Metallica DON FELDER KIRK HAMMETT NANCY WILSON formerly of the Eagles of Metallica of Heart FAST FACTS 13M+ 338 8M+ INDUCTEES FANS HAVE VISITED FAN VOTES IN THE ROCK & ROLL THE MUSEUM CAST FOR THE HALL OF FAME CLASS OF 2020 2.3K+ 35K+ ARTISITS & VIPS ONE-OF-A-KIND TOURED IN 2019 ARTIFACTS 2020 ON A ROLL 20-20 COVID-19: THIS WAS NOT THE PLAN What a difference a year makes 2019 2020 What a difference a year makes 2019 2020 What a difference a year makes 2019 2020 OUR TARGET Music Fan 2 local 11% regional 40% national 41% global 8% 2020 18 DRIVE CONVERSION visit join attend support shop partner share host 2020 PIVOT: STRATEGIC priority BLOW OUT DIGITAL TO Grow, ENGAGE & CONVERT targets to ENGAGE Educators Media Partners Music Fans (Segment 2s) Digital / Current + Current + Social Prospective Ecommerce Prospective Partners + Members -

'Music and Remembrance: Britain and the First World War'

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Grant, P. and Hanna, E. (2014). Music and Remembrance. In: Lowe, D. and Joel, T. (Eds.), Remembering the First World War. (pp. 110-126). Routledge/Taylor and Francis. ISBN 9780415856287 This is the accepted version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/16364/ Link to published version: Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] ‘Music and Remembrance: Britain and the First World War’ Dr Peter Grant (City University, UK) & Dr Emma Hanna (U. of Greenwich, UK) Introduction In his research using a Mass Observation study, John Sloboda found that the most valued outcome people place on listening to music is the remembrance of past events.1 While music has been a relatively neglected area in our understanding of the cultural history and legacy of 1914-18, a number of historians are now examining the significance of the music produced both during and after the war.2 This chapter analyses the scope and variety of musical responses to the war, from the time of the war itself to the present, with reference to both ‘high’ and ‘popular’ music in Britain’s remembrance of the Great War. -

Video Games and the Mobilization of Anxiety and Desire

PLAYING THE CRISIS: VIDEO GAMES AND THE MOBILIZATION OF ANXIETY AND DESIRE BY ROBERT MEJIA DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Communications in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2012 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor Kent A. Ono, Chair Professor John Nerone Professor Clifford Christians Professor Robert A. Brookey, Northern Illinois University ABSTRACT This is a critical cultural and political economic analysis of the video game as an engine of global anxiety and desire. Attempting to move beyond conventional studies of the video game as a thing-in-itself, relatively self-contained as a textual, ludic, or even technological (in the narrow sense of the word) phenomenon, I propose that gaming has come to operate as an epistemological imperative that extends beyond the site of gaming in itself. Play and pleasure have come to affect sites of culture and the structural formation of various populations beyond those conceived of as belonging to conventional gaming populations: the workplace, consumer experiences, education, warfare, and even the practice of politics itself, amongst other domains. Indeed, the central claim of this dissertation is that the video game operates with the same political and cultural gravity as that ascribed to the prison by Michel Foucault. That is, just as the prison operated as the discursive site wherein the disciplinary imaginary was honed, so too does digital play operate as that discursive site wherein the ludic imperative has emerged. To make this claim, I have had to move beyond the conventional theoretical frameworks utilized in the analysis of video games. -

WITH OUR DEMONS a Thesis Submitted By

1 MONSTROSITIES MADE IN THE INTERFACE: THE IDEOLOGICAL RAMIFICATIONS OF ‘PLAYING’ WITH OUR DEMONS A Thesis submitted by Jesse J Warren, BLM Student ID: u1060927 For the award of Master of Arts (Humanities and Communication) 2020 Thesis Certification Page This thesis is entirely the work of Jesse Warren except where otherwise acknowledged. This work is original and has not previously been submitted for any other award, except where acknowledged. Signed by the candidate: __________________________________________________________________ Principal Supervisor: _________________________________________________________________ Abstract Using procedural rhetoric to critique the role of the monster in survival horror video games, this dissertation will discuss the potential for such monsters to embody ideological antagonism in the ‘game’ world which is symptomatic of the desire to simulate the ideological antagonism existing in the ‘real’ world. Survival video games explore ideology by offering a space in which to fantasise about society's fears and desires in which the sum of all fears and object of greatest desire (the monster) is so terrifying as it embodies everything 'other' than acceptable, enculturated social and political behaviour. Video games rely on ideology to create believable game worlds as well as simulate believable behaviours, and in the case of survival horror video games, to simulate fear. This dissertation will critique how the games Alien:Isolation, Until Dawn, and The Walking Dead Season 1 construct and themselves critique representations of the ‘real’ world, specifically the way these games position the player to see the monster as an embodiment of everything wrong and evil in life - everything 'other' than an ideal, peaceful existence, and challenge the player to recognise that the very actions required to combat or survive this force potentially serve as both extensions of existing cultural ideology and harbingers of ideological resistance across two worlds – the ‘real’ and the ‘game’. -

Fragile, Emergent, and Absent Tonics in Pop and Rock Songs *

Fragile, Emergent, and Absent Tonics in Pop and Rock Songs * Mark Spicer NOTE: The examples for the (text-only) PDF version of this item are available online at: h'p://www.mtosmt.org/issues/mto.17.23..(mto.17.23.2.spicer.php 0E1WORDS: tonality, popular song, rock harmony, ragile tonics, emergent tonics, absent tonics, soul dominant, Sisyphus e3ect A4STRACT: This article explores the sometimes tricky 6uestion o tonality in pop and rock songs by positing three tonal scenarios: 1) songs with a fragile tonic, in which the tonic chord is present but its hierarchical status is weakened, either by relegating the tonic to a more unstable chord in 7rst or second inversion or by positioning the tonic mid-phrase rather than at structural points o departure or arrival8 .) songs with an emergent tonic, in which the tonic chord is initially absent yet deliberately saved or a triumphant arrival later in the song, usually at the onset o the chorus8 and 3) songs with an absent tonic, an extreme case in which the promised tonic chord never actually materiali9es. In each o these scenarios, the composer’s toying with tonality and listeners’ expectations may be considered hermeneutically as a means o enriching the song’s overall message. Close analyses o songs with ragile, emergent, and absent tonics are o3ered, drawing representative examples rom a wide range o styles and genres across the past 7 ty years o popular music, including 1960s Motown, 1970s soul, 1980s synthpop, 1990s alternative rock, and recent A.S. and A.0. B1 hits. Received November 2016 Colume 23, Number 2, Dune 2017 Copyright © 2017 Society for Music Theory F,G Skilled nineteenth-century song composers such as Robert Schumann and Dohannes 4rahms o ten exploited tonality and its expectations or symbolic or expressive purposes. -

Mixed Media December Online Supplement | Long Island Pulse

Mixed Media December Online Supplement | Long Island Pulse http://www.lipulse.com/blog/article/mixed-media-december-online-supp... currently 43°F and mostly cloudy on Long Island search advertise | subscribe | free issue Mixed Media December Online Supplement Published: Wednesday, December 09, 2009 U.K. Music Travelouge Get Yer Ya-Ya’s Out and Gimmie Shelter As a followup to our profile of rock photographer Ethan Russell in the November issue, we will now give a little more information on the just-released Rolling Stones projects we discussed with Russell. First up is the reissue of the Rolling Stones album Get Yer Ya-Ya’s Out!. What many consider the best live rock concert album of all time is now available from Abcko in a four-disc box set. Along with the original album there is a disc of five previously unreleased live performances and a DVD of those performances. There is a also a bonus CD of five live tracks from B.B. King and seven from Ike & Tina Turner, who were the opening acts on the tour. There is also a beautiful hardcover book with an essay by Russell, his photographs, fans’ notes and expanded liner notes, along with a lobby card-sized reproduction of the tour poster. Russell’s new book, Let It Bleed (Springboard), is now finally out and it’s a stunning visual look back on the infamous tour and the watershed Altamont concert. Russell doesn’t just provide his historic photos (which would be sufficient), but, like in his previous Dear Mr. Fantasy book, he serves as an insightful eyewitness of the greatest rock tour in history and rock music’s 60’s live Waterloo. -

2011 – Cincinnati, OH

Society for American Music Thirty-Seventh Annual Conference International Association for the Study of Popular Music, U.S. Branch Time Keeps On Slipping: Popular Music Histories Hosted by the College-Conservatory of Music University of Cincinnati Hilton Cincinnati Netherland Plaza 9–13 March 2011 Cincinnati, Ohio Mission of the Society for American Music he mission of the Society for American Music Tis to stimulate the appreciation, performance, creation, and study of American musics of all eras and in all their diversity, including the full range of activities and institutions associated with these musics throughout the world. ounded and first named in honor of Oscar Sonneck (1873–1928), early Chief of the Library of Congress Music Division and the F pioneer scholar of American music, the Society for American Music is a constituent member of the American Council of Learned Societies. It is designated as a tax-exempt organization, 501(c)(3), by the Internal Revenue Service. Conferences held each year in the early spring give members the opportunity to share information and ideas, to hear performances, and to enjoy the company of others with similar interests. The Society publishes three periodicals. The Journal of the Society for American Music, a quarterly journal, is published for the Society by Cambridge University Press. Contents are chosen through review by a distinguished editorial advisory board representing the many subjects and professions within the field of American music.The Society for American Music Bulletin is published three times yearly and provides a timely and informal means by which members communicate with each other. The annual Directory provides a list of members, their postal and email addresses, and telephone and fax numbers. -

A Sense of Unending: Apocalypse and Post-Apocalypse in Novels of Late Capitalism" (2019)

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville ScholarWorks@UARK Theses and Dissertations 8-2019 A Sense of Unending: Apocalypse and Post- Apocalypse in Novels of Late Capitalism Brent Linsley University of Arkansas, Fayetteville Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd Part of the American Literature Commons, Literature in English, North America Commons, and the Modern Literature Commons Recommended Citation Linsley, Brent, "A Sense of Unending: Apocalypse and Post-Apocalypse in Novels of Late Capitalism" (2019). Theses and Dissertations. 3341. https://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/3341 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Sense of Unending: Apocalypse and Post-Apocalypse in Novels of Late Capitalism A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English by Brent Linsley Henderson State University Bachelor of Arts in English, 2000 Henderson State University Master of Liberal Arts in English, 2005 August 2019 University of Arkansas This dissertation is approved for recommendation to the Graduate Council. _____________________________________ M. Keith Booker, Ph.D. Dissertation Director _____________________________________ ______________________________________ Robert Cochran, Ph.D. Susan Marren, Ph.D. Committee Member Committee Member Abstract From Frank Kermode to Norman Cohn to John Hall, scholars agree that apocalypse historically has represented times of radical change to social and political systems as older orders are wiped away and replaced by a realignment of respective norms. This paradigm is predicated upon an understanding of apocalypse that emphasizes the rebuilding of communities after catastrophe has occurred. -

Jon Batiste and Stay Human's

WIN! A $3,695 BUCKS COUNTY/ZILDJIAN PACKAGE THE WORLD’S #1 DRUM MAGAZINE 6 WAYS TO PLAY SMOOTHER ROLLS BUILD YOUR OWN COCKTAIL KIT Jon Batiste and Stay Human’s Joe Saylor RUMMER M D A RN G E A Late-Night Deep Grooves Z D I O N E M • • T e h n i 40 e z W a YEARS g o a r Of Excellence l d M ’ s # m 1 u r D CLIFF ALMOND CAMILO, KRANTZ, AND BEYOND KEVIN MARCH APRIL 2016 ROBERT POLLARD’S GO-TO GUY HUGH GRUNDY AND HIS ZOMBIES “ODESSEY” 12 Modern Drummer June 2014 .350" .590" .610" .620" .610" .600" .590" “It is balanced, it is powerful. It is the .580" Wicked Piston!” Mike Mangini Dream Theater L. 16 3/4" • 42.55cm | D .580" • 1.47cm VHMMWP Mike Mangini’s new unique design starts out at .580” in the grip and UNIQUE TOP WEIGHTED DESIGN UNIQUE TOP increases slightly towards the middle of the stick until it reaches .620” and then tapers back down to an acorn tip. Mike’s reason for this design is so that the stick has a slightly added front weight for a solid, consistent “throw” and transient sound. With the extra length, you can adjust how much front weight you’re implementing by slightly moving your fulcrum .580" point up or down on the stick. You’ll also get a fat sounding rimshot crack from the added front weighted taper. Hickory. #SWITCHTOVATER See a full video of Mike explaining the Wicked Piston at vater.com remo_tamb-saylor_md-0416.pdf 1 12/18/15 11:43 AM 270 Centre Street | Holbrook, MA 02343 | 1.781.767.1877 | [email protected] VATER.COM C M Y K CM MY CY CMY .350" .590" .610" .620" .610" .600" .590" “It is balanced, it is powerful. -

Battleswithbitsofrubber.Com Page 1 CONTENTS

battleswithbitsofrubber.com Page 1 CONTENTS Credits and thanks....................................................................................... Page 3 Foreword by Joe Nazzaro ........................................................................... Page 4 Introduction ................................................................................................. Page 5 Effects in chronological order 1. ‘Haven’t you had your tea?’ ................................................................... Page 6 2. ‘In the garden ... there’s a girl’................................................................ Page 7 3. ‘He’s got an arm off...’ ............................................................................. Page 9 4. ‘Which one do you want? Girl or bloke?’ ........................................... Page 11 5. ‘We take care of Philip.’ .......................................................................... Page 13 6. ‘We’re gonna borrow your car, okay...’ ................................................ Page 13 7. ‘I guess we’ll have to take the Jag.’ ...................................................... Page 14 8. ‘I’ll just flip the mains breakers...’ ........................................................ Page 15 9. ‘I didn’t want to say anything.’.............................................................. Page 16 10. ‘Cock it!’.................................................................................................. Page 17 11. ‘I’m sorry Mum.’ .....................................................................................