Notes of Conversation with Wilf Smith. 3 July 1997 Farmed About 100 Acres

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

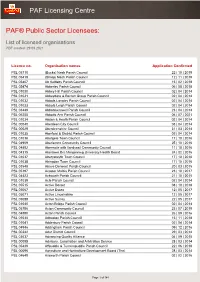

List of Licensed Organisations PDF Created: 29 09 2021

PAF Licensing Centre PAF® Public Sector Licensees: List of licensed organisations PDF created: 29 09 2021 Licence no. Organisation names Application Confirmed PSL 05710 (Bucks) Nash Parish Council 22 | 10 | 2019 PSL 05419 (Shrop) Nash Parish Council 12 | 11 | 2019 PSL 05407 Ab Kettleby Parish Council 15 | 02 | 2018 PSL 05474 Abberley Parish Council 06 | 08 | 2018 PSL 01030 Abbey Hill Parish Council 02 | 04 | 2014 PSL 01031 Abbeydore & Bacton Group Parish Council 02 | 04 | 2014 PSL 01032 Abbots Langley Parish Council 02 | 04 | 2014 PSL 01033 Abbots Leigh Parish Council 02 | 04 | 2014 PSL 03449 Abbotskerswell Parish Council 23 | 04 | 2014 PSL 06255 Abbotts Ann Parish Council 06 | 07 | 2021 PSL 01034 Abdon & Heath Parish Council 02 | 04 | 2014 PSL 00040 Aberdeen City Council 03 | 04 | 2014 PSL 00029 Aberdeenshire Council 31 | 03 | 2014 PSL 01035 Aberford & District Parish Council 02 | 04 | 2014 PSL 01036 Abergele Town Council 17 | 10 | 2016 PSL 04909 Aberlemno Community Council 25 | 10 | 2016 PSL 04892 Abermule with llandyssil Community Council 11 | 10 | 2016 PSL 04315 Abertawe Bro Morgannwg University Health Board 24 | 02 | 2016 PSL 01037 Aberystwyth Town Council 17 | 10 | 2016 PSL 01038 Abingdon Town Council 17 | 10 | 2016 PSL 03548 Above Derwent Parish Council 20 | 03 | 2015 PSL 05197 Acaster Malbis Parish Council 23 | 10 | 2017 PSL 04423 Ackworth Parish Council 21 | 10 | 2015 PSL 01039 Acle Parish Council 02 | 04 | 2014 PSL 05515 Active Dorset 08 | 10 | 2018 PSL 05067 Active Essex 12 | 05 | 2017 PSL 05071 Active Lincolnshire 12 | 05 -

The Magazine of RAF 100 Group Association

The magazine of RAF 100 Group Association RAF 100 Group Association Chairman Roger Dobson: Tel: 01407 710384 RAF 100 Group Association Secretary Janine Harrington: Tel: 01723 512544 Email: [email protected] Home to RAF 100 Group Association Memorabilia City of Norwich Aviation Museum Old Norwich Road, Horsham St Faith, Norwich, Norfolk NR10 3JF Telephone: 01603 893080 www.cnam.org.uk 2 Dearest Kindred Spirits, A very HAPPY NEW YEAR to you all! And a heartfelt THANK YOU for all the wonderful Christmas gifts, flowers, letters and cards I received. Words cannot express how much they mean, just be assured that each and every one of you is truly valued xx My first challenge of the New Year was changing back to my maiden name … something of a relief, I have to say. However, it’s not as easy as it sounds! The bank clerk when she finally gets to me in the queue, informs me I can’t simply think up a new name and expect them to play ball!! But hey, this was the name I was born with? It took a flurry of evidential documents, taxis back and forth into town, and then some, before finally the dastardly deed was done. My second challenge is this year’s Reunion. What a challenge it is turning out to be!! Just as I thought it was all prepared, everything sorted, all the balls were suddenly in the air again. However, now, it really is something to celebrate, as it becomes our honour and privilege to be joined by the present-day U.S. -

Four Decades Airfield Research Group Magazine

A IRFIELD R ESEARCH G ROUP M AGAZINE . C ONTENTS TO J UNE 2017 Four Decades of the Airfield Research Group Magazine Contents Index from December 1977 to June 2017 1 9 7 7 1 9 8 7 1 9 9 7 6 pages 28 pages 40 pages © Airfield Research Group 2017 2 0 0 7 2 0 1 7 40 pages Version 2: July 2017 48 pages Page 1 File version: July 2017 A IRFIELD R ESEARCH G ROUP M AGAZINE . C ONTENTS TO J UNE 2017 AIRFIELD REVIEW The Journal of the Airfield Research Group The journal was initially called Airfield Report , then ARG Newsletter, finally becoming Airfield Review in 1985. The number of pages has varied from initially just 6, occasio- nally to up to 60 (a few issues in c.2004). Typically 44, recent journals have been 48. There appear to have been three versions of the ARG index/ table of contents produced for the magazine since its conception. The first was that by David Hall c.1986, which was a very detailed publication and was extensively cross-referenced. For example if an article contained the sentence, ‘The squadron’s flights were temporarily located at Tangmere and Kenley’, then both sites would appear in the index. It also included titles of ‘Books Reviewed’ etc Since then the list has been considerably simplified with only article headings noted. I suspect that to create a current cross-reference list would take around a day per magazine which equates to around eight months work and is clearly impractical. The second version was then created in December 2009 by Richard Flagg with help from Peter Howarth, Bill Taylor, Ray Towler and myself. -

St. Lawrence, Gnosall

St. Lawrence, Gnosall - St Mary's, Moreton & Christ Church, Knightley - Burials - Name order Green background = Gnosall Churchyard Cream background = Gnosall Cemetery Red text = Moreton register Green text = Knightley register Register Page Item Row-Plot Christian Names Surname Burial Date Age Comments 1572-1777 (blank) (blank) 31/03/1762 "son of" - Father: (blank) - Mother:Elizabeth 1572-1777 (blank) (blank) 14/05/1769 "daughter of" - Father:John - Mother:Ann 1572-1777 Elizabeth (illegible) 03/12/1738 a travellers child - bapt. 01/12/1739 1572-1777 Thomas *Bates 04/02/1738 *unclear whether buried or baptized - Father:Edward - Mother:Elizabeth 1572-1777 William *Bromley 18/11/1737 *unclear whether buried or baptized - Father:Thomas - Mother:Mary 1572-1777 Richard_ /harding 01/05/1659 1572-1777 John 'Bayne or Bayle' 01/10/1642 'a tall young man, one of the King's souldiers' 1572-1777 Edward Daye 29/03/1619 - Father:John 1572-1777 Ann (blank) 28/05/1745 a traveller - Father:George 1572-1777 Elizabeth (Blank) 12/08/1639 of Alston 1572-1777 Sarah (blank) 17/05/1773 1572-1777 Mary (not entered) 17/04/1769 of Forton - Mother:Sarah 1572-1777 .. .. 19/05/1625 unknown gender; "a poor childe" 1572-1777 John ..dge_ 23/02/1686 - Father:John 1572-1777 [missing] [missing] 15/12/1656 g/u; of Knightley 1572-1777 Adam [missing] 07/11/1661 1572-1777 Edward [missing] __/11/1661 - Mother:Mary 1572-1777 Marie [missing] __/08/1656 - Father:[missing], gent. - Mother:Alice 1572-1777 __ __ 02/07/1702 g/u 1572-1777 Elizabeth __ __/12/1761 - Father:Nathaniel_ - Mother:Mary 1572-1777 Elizabeth _-in-ton 30/05/1594 _Kingston 1572-1777 Mary _-orsl-s 08/05/1703 1572-1777 ….or _Protles_ 02/04/1699 fem. -

A Challenge Designed to Explore the County We All Know and Love! WELCOME

A challenge designed to explore the county we all know and love! WELCOME Welcome to our ‘I Love Staffordshire’ challenge! This challenge aims to teach you more about the county where we live as well as having lots of fun working through our challenges. Girlguiding Staffordshire is split into 17 divisions across the county. Every single Rainbow, Brownie, Guide, Ranger, Young Leader, Unit Helper, Leader, Trefoil Guild Member and Occassional Helper belongs to one of our divisions. To earn the ‘I Love Staffordshire’ challenge badge simply choose and complete one challenge from each of our divisions. You can choose to complete the Outdoor, Food, Craft or Pen & Paper challenge for each division depending on which one appeals to you the most. Some of the challenges will require adult supervision and so please remember to ask for help if you need it. There are lots of ideas in this pack but you can always search online to find extra instructions or guidance for some of the challenges. You can also be creative and adapt the challenges if you don’t have all of the equipment and/or ingredients. We’d love you to share your successes with us so please email your photos or videos to [email protected] and we’ll add them to an online photo album so we can all see how everyone is getting on. Once you have completed your challenges then you can order a badge to celebrate your success by visiting girlguidingstaffordshire.org.uk/shop We hope that you enjoy completing our ‘I Love Staffordshire’ challenge. -

International Passenger Survey, 2009

UK Data Archive Study Number 6255 -International Passenger Survey, 2009 Airline code Airline name Code /Au1 /Australia - dump code 50099 /Au2 /Austria - dump code 21099 /Ba /Barbados - dump code 70599 /Be1 /Belgium - dump code 05099 /Be2 /Benin - dump code 45099 /Br /Brazil - dump code 76199 /Ca /Canada - dump code 80099 /Ch /Chile - dump code 76499 /Co /Costa Rica - dump code 77199 /De /Denmark - dump code 12099 /Ei /Ei EIRE dump code 02190 /Fi /Finland - dump code 17099 /Fr /France - dump code 07099 /Ge /Germany - dump code 08099 /Gr /Greece - dump code 22099 /Gu /Guatemala - dump code 77399 /Ho /Honduras - dump code 77499 /Ic /Iceland - dump code 02099 /In /India - dump code 61099 /Ir /Irish Rep - dump code 02199 /Is /Israel - dump code 57099 /It /Italy - dump code 10099 /Ja /Japan - dump code 62099 /Ka /Kampuchea - dump code 65499 /Ke /Kenya - dump code 41099 /La /Latvia - dump code 31799 /Le /Lebanon - dump code 57499 /Lu /Luxembourg - dump code 06099 /Ma /Macedonia - dump code 27399 /Me /Mexico - dump code 76299 /Mo /Montenegro - dump code 27499 /NA /Nauru (Dump) 54099 /Ne1 /Netherlands - dump code 11099 /Ne2 /New Guinea - dump code 53099 /Ne3 /New Zealand - dump code 51099 /Ni /Nigeria - dump code 40299 /No /Norway - dump code 18099 /Pa /Pakistan - dump code 65099 /Pe /Peru - dump code 76899 /Po /Portugal - dump code 23099 /Ro /Romania - dump code 30199 /Ru /Russia - dump code 30999 /Sa /Saudi Arabia - dump code 57599 /Se /Serbia - dump code 27599 /Sl /Slovenia - dump code 27699 /So1 /Somalia - dump code 48199 /So2 /South Africa -

A MEETING of the BOROUGH of TELFORD & WREKIN Will Be Held

A MEETING OF THE BOROUGH OF TELFORD & WREKIN Will be held at THE PLACE, OAKENGATES, TELFORD TF2 6ET on THURSDAY, 23 NOVEMBER 2017 at 6.00pm All Members are summoned to attend for the transaction of the under mentioned business Assistant Director Governance, Procurement & Commissioning _______________________________________________________ AGENDA 1. Prayers 2. Apologies for Absence 3. Declarations of Interest 4. Minutes of the Council Appendix A To confirm the minutes of the meeting of the Council held on 21 White September 2017. Page 6 5. Leader’s Report & Announcements The Leader of the Council may give an oral report on matters of significance to the Borough, comment upon the Cabinet decisions or make any announcements. 6. Mayor’s Announcements Appendix B To note the Mayoral Engagements undertaken since the Council White meeting held on 21 September 2017. Page 14 Announcement Members of the Telford & Wrekin Fairtrade Alliance will present to the Council the Certificate of Fairtrade Status from the Fairtrade Foundation. 7. Public Questions To receive any questions from the public which have been submitted under Council Procedure Rules 7.11 and 7.12. The session will last no more than 15 minutes with a maximum of 2 minutes allowed for each question and answer. Questions can be asked of The Leader and Cabinet Members. (i) The following question to Cllr Angela McClements, White Ribbon Champion and Cabinet Member: Transport, Infrastructure & Broadband and has been submitted by Carol Scott MBE JP: “What provision is there in Telford & Wrekin for the early intervention of specialist services for victims of Domestic Abuse and how does this compare to what is offered in Shropshire, is there a specific training safeguarding officer or equivalent?” 8. -

Southern Staffordshire Outline Water Cycle Study Final Report

INSERT YOUR PICTURE(S) IN THIS CELL Southern Staffordshire Outline Water Cycle Study Final Report Stafford Borough, Lichfield District, Tamworth Borough, South Staffordshire District and Cannock Chase District Councils July 2010 Final Report 9V5955 CONTENTS Page 1 INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 General Overview 1 1.2 Scope 1 1.3 Objectives of the Water Cycle Study 2 2 DATA COLLECTION AND METHODOLOGY 3 2.1 Overview 3 2.2 Data Collection and Guidance on the use of this Study 3 2.3 Housing Growth and Employment Trajectories 4 2.4 Flood Risk 5 2.5 Water Resources and Supply 6 2.6 Wastewater Collection and Treatment 7 2.7 Water Quality and Environmental Issues 7 2.8 Development Area Actions 8 2.9 Data Limitations 8 3 STRATEGIC ASSESSMENTS 9 3.1 Water Supply and Resources 9 3.1.1 Water Resources 9 3.1.2 Severn Trent Water Limited 12 3.1.3 South Staffordshire Water 20 3.1.4 Environment Agency 24 3.1.5 Non Residential Water Use 32 3.1.6 Canal Network 32 3.1.7 Conclusions 33 3.2 Wastewater Collection and Treatment 34 3.2.1 Introduction 34 3.2.2 Wastewater Infrastructure 35 3.2.3 STWL Generic WCS Response 36 3.2.4 Wastewater Treatment 38 3.3 Water Quality and Environmental Issues 44 3.3.1 Introduction 44 3.3.2 Directives 44 3.3.3 River Quality 45 3.3.4 Effect of Development upon Water Quality 46 3.3.5 Designated Sites 47 3.3.6 Effect of WwTWs on Water Quality 47 3.3.7 Effect of Agricultural Practices on Water Quality 47 3.4 Flood Risk 50 3.4.1 Introduction 50 3.4.2 Environment Agency Flood Maps 51 3.4.3 SFRAs 52 3.4.4 Regional Flood Risk Appraisal (RFRA) 53 -

The Aldwark Chronicle

The Aldwark chronicle Newsletter of the Royal Air Forces Association York Branch Branch Headquarters: 3-5 Aldwark York YO1 7BX Telephone: 07495 651849 Our Website: www.rafayork.org Club opening hours: Thu: 7.30 pm to 10.30 pm, Sat: Currently closed. Branch Charity Number 500974 Current membership: 488 IssueAugust No2020 73 August 20201 York Branch & Club Official Appointments for 2020-21 President: Mr R W Gray President Emeritus Air Commodore W G Gambold RAF (Retd) Life Vice-Presidents: Mr H R Kidd OBE Mr J J Mawson Vice-Presidents: Mr J Allison BEM Ms S Richmond Branch Chairman Mr B R Mennell [email protected] Branch Vice-Chairman Mr R Ford Branch Hon. Secretary Mr A M Bryne [email protected] Branch Hon. Treasurer Mr D Pollard [email protected] Membership Secretary Mr R Woods Welfare Officer Mr R Ford [email protected] Wings Appeal Organiser Mr I Smith [email protected] N. Area & Annual Conf. Rep. Mr R Ford Branch Standard Bearer Mr G Murden Deputy Standard Bearer Mr A Gunn Public Relations Officer Mr A M Bryne Buildings Officer Mr R Webster Website Manager Mrs M Barter [email protected] Club Chairperson Mrs M Barter Club Deputy Chairperson Mrs P Harrington Club Hon Secretary Mrs J Potter Club Hon. Treasurer Mr A Ramsbottom Club Bar Manager Mrs J Snelling Club Deputy Bar Manager Mr S Edgar Club Fundraising Officer Mrs G McCarthy Club Social Secretary Mr J Forrester Club Tea Bar Manager Mrs D Mennell Club Trustees: Ms S Richmond, Mrs K Woods , Mr R Webster Aldwark Chronicle Editor Mr A M Bryne Please address all general enquiries to the Branch Secretary. -

Important Information

Post Office Ltd Network Change Programme Area Plan Proposal Shropshire and Staffordshire 2 Contents 1. Introduction 2. Proposed Local Area Plan 3. The Role of Postwatch 4. Proposed Outreach service Points 5. List of Post Office® branches proposed for “Outreach” 6. List of Post Office® branches proposed for closure 7. List of Post Office® branches proposed to remain in the Network • Frequently Asked Questions Leaflet • Map of the Local Area Plan • Branch Access Reports - information on proposed closing branches, replacement Outreach services and details of alternative branches in the Area 3 4 1. Introduction The Government has recognised that fewer people are using Post Office® branches, partly because traditional services, including benefit payments and other services are now available in other ways, such as online or directly through banks. It has concluded that the overall size and shape of the network of Post Office® branches (“the Network”) needs to change. In May 2007, following a national public consultation, the Government announced a range of proposed measures to modernise and reshape the Network and put it on a more stable footing for the future. A copy of the Government’s response to the national public consultation (“the Response Document”) can be obtained at www.dti.gov.uk/consultations/page36024.html. Post Office Ltd has now put in place a Network Change Programme (“the Programme”) to implement the measures proposed by the Government. The Programme will involve the compulsory compensated closure of up to 2,500 Post Office® branches (out of a current Network of 14,000 branches), with the introduction of about 500 service points known as “Outreaches” to mitigate the impact of the proposed closures. -

The Plan for Stafford Borough Part 2 Submission Consultation Statement

Submission Consultation Statement (Regulation 22) The Plan for Stafford Borough Part 2 Submission Consultation Statement (Regulation 22) March 2016 1 Submission Consultation Statement (Regulation 22) Contents 1. Submission Consultation Statement (Regulation 22(1) (c)) 2. Regulation 18 Statement 3. Regulation 20 Statement 4. Next Steps 2 Submission Consultation Statement (Regulation 22) 1. Submission Consultation Statement (Reg. 22 (1)(c)) 3 Submission Consultation Statement (Regulation 22) 1 Submission Consultation Statement (Reg. 22 (1)(c)) 1.1 This Consultation Statement (Reg 22(1)(c)) has been prepared to meet the requirements set out in Regulation 22 of the Town and Country Planning (Local Planning) (England) Regulations 2012, which came into force on 6 April 2012, regarding the submission of documents and information to the Secretary of State in order to progress through the Examination process. In particular section c of Regulation 22 defines the following requirement: Submission of documents and information to the Secretary of State 22. – (1) The documents prescribed for the purposes of section 20(3) of the Act are – (c) a statement setting out – (i) which bodies and persons the local planning authority invited to make representations under regulation 18, (ii) how those bodies and persons were invited to make representations under regulation 18, (iii) a summary of the main issues raised by the representations made pursuant to regulation 18, (iv) how any representations made pursuant to regulation 18 have been taken into account; (v) if representations were made pursuant to regulation 20, the number of representations made and a summary of the main issues raised in those representations; and (vi) if no representations were made in regulation 20, that no such representations were made. -

Analysis of Airprox in UK Airspace: January to June 2006

Sixteenth Report by the UK Airprox Board: ‘Analysis of Airprox in UK Airspace’ (January 2006 to June 2006) produced jointly for The Chairman, Civil Aviation Authority and the Chief of the Air Staff, Royal Air Force FOREWORD The primary purpose of this, the sixteenth Report from the UK Airprox Board (UKAB), is to promote air safety awareness and understanding of Airprox. “Book 16” covers the first six months of 2006 in detail, containing findings on the 79 Airprox which were reported as occurring within UK airspace in that period and which were fully investigated and as- sessed by the Airprox Board. The count of 79 incidents during the first six months of 2006 is 17 fewer than the aver- age of comparable figures in each of the previous five years. The Table below shows the details. The reader is invited to note that the figure of 79 is the lowest total in the dataset. Also at their lowest values are the figures for Risk A and Risk B occurrences in the first six months of 2006, at four and 21 respectively. These facts need to be kept in mind when reviewing other data, especially percentages, in this Report. Risk Category 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 A 16 7 6 8 1 4 B 2 27 29 0 26 21 C 57 56 49 66 5 54 D 5 2 1 5 0 0 Totals: 101 92 85 109 92 79 Although this Report is primarily concerned with aircraft operations across a wide spectrum of aerial activities, it is understandable that people generally are interested in the safety of commercial air transport (CAT).