Maine's Open Lands: Public Use of Private Land, the Right to Roam and the Right to Exclude

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Right-Of-Way

HD-1301 Chapter RIGHT-OF-WAY Subject General Information GENERAL: The procurement of right of way to widths that accommodate the construction, adequate drainage, and proper maintenance of the highway is a very important part of the overall project. Adequate right-of-way widths permit the construction of gentle slopes, resulting in more safety for the motorist and allowing easier and more economical maintenance. Traffic requirements, topography, environmental issues, utilities, land use, costs, intersection design, and extent of ultimate expansion influence the width of right of way for the complete development of a roadway. RIGHT-OF-WAY WIDTH: Right of way should be of sufficient width to accommodate construction and the continued maintenance and operation of the facility. Avoiding right-angle breaks in the right-of-way line and irregularities in widths facilitates maintenance operations and fencing and optimizes land use. Consider the use of curb-and-gutter sections in urbanized areas for the reduction of right-of-way widths and compatibility with adjacent development. The use of right of way, permanent easements, and temporary easements should be determined on a site-specific basis in order to facilitate the construction, operation, and maintenance of the facility and adjacent land use. Typically, permanent right of way should be acquired to the back edge of the berm on curb-and-gutter projects with easements used for that portion beyond the right of way for construction, operation, and maintenance of drainage structures. EASEMENTS: It is common practice to use two types of easements on proposed highway projects: temporary and permanent. Temporary Easement—A temporary easement is the use of a tract of land for a specified time duration (typically the duration of construction), with the land reverting to the owner’s exclusive use at the end of the period. -

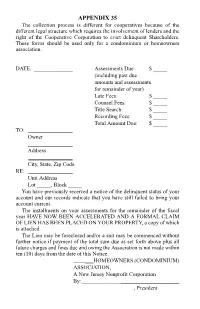

35. Notice of Acceleration of Assessment and Filing of Lien; Claim of Lien

APPENDIX 35 The collection process is different for cooperatives because of the different legal structure which requires the involvement of lenders and the right of the Cooperative Corporation to evict delinquent Shareholders. These forms should be used only for a condominium or homeowners association. DATE: ______________ Assessments Due: $ _____ (including past due amounts and assessments for remainder of year) Late Fees: $ _____ Counsel Fees: $ _____ Title Search: $ _____ Recording Fees: $ _____ Total Amount Due: $ _____ TO: ________________ Owner ________________ Address ________________ City, State, Zip Code RE: ________________ Unit Address Lot _____, Block _____ You have previously received a notice of the delinquent status of your account and our records indicate that you have still failed to bring your account current. The installments on your assessments for the remainder of the fiscal year HAVE NOW BEEN ACCELERATED AND A FORMAL CLAIM OF LIEN HAS BEEN PLACED ON YOUR PROPERTY, a copy of which is attached. The Lien may be foreclosed and/or a suit may be commenced without further notice if payment of the total sum due as set forth above plus all future charges and fines due and owing the Association is not made within ten (10) days from the date of this Notice. ___HOMEOWNERS (CONDOMINIUM) ASSOCIATION, A New Jersey Nonprofit Corporation By: _____________________ , President CLAIM OF LIEN CLAIM OF LIEN _________ Homeowners (Condominium) Association, Inc., a New Jersey nonprofit corporation (“Association”), with an address at , , New Jersey, , in care of (Management Company) , hereby claims a lien for unpaid assessments, charges and expenses in accordance with the terms of that certain Declaration of Covenants and Restrictions (“Declaration”) or Master Deed (“Master Deed”) for _______ recorded on in the County Clerk's Office in Deed Book Page et seq. -

G.S. 45-36.24 Page 1 § 45-36.24. Expiration of Lien of Security

§ 45-36.24. Expiration of lien of security instrument. (a) Maturity Date. – For purposes of this section: (1) If a secured obligation is for the payment of money: a. If all remaining sums owing on the secured obligation are due and payable in full on a date specified in the secured obligation, the maturity date of the secured obligation is the date so specified. If no such date is specified in the secured obligation, the maturity date of the secured obligation is the last date a payment on the secured obligation is due and payable under the terms of the secured obligation. b. If all remaining sums owing on the secured obligation are due and payable in full on demand or on a date specified in the secured obligation, whichever first occurs, the maturity date of the secured obligation is the date so specified. If all sums owing on the secured obligation are due and payable in full on demand and no alternative date is specified in the secured obligation for payment in full, the maturity date of the secured obligation is the date of the secured obligation. c. The maturity date of the secured obligation is "stated" in a security instrument if (i) the maturity date of the secured obligation is specified as a date certain in the security instrument, (ii) the last date a payment on the secured obligation is due and payable under the terms of the secured obligation is specified in the security instrument, or (iii) the maturity date of the secured obligation or the last date a payment on the secured obligation is due and payable under the terms of the secured obligation can be ascertained or determined from information contained in the security instrument, such as, for example, from a payment schedule contained in the security instrument. -

The Navigability Concept in the Civil and Common Law: Historical Development, Current Importance, and Some Doctrines That Don't Hold Water

Florida State University Law Review Volume 3 Issue 4 Article 1 Fall 1975 The Navigability Concept in the Civil and Common Law: Historical Development, Current Importance, and Some Doctrines That Don't Hold Water Glenn J. MacGrady Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.law.fsu.edu/lr Part of the Admiralty Commons, and the Water Law Commons Recommended Citation Glenn J. MacGrady, The Navigability Concept in the Civil and Common Law: Historical Development, Current Importance, and Some Doctrines That Don't Hold Water, 3 Fla. St. U. L. Rev. 511 (1975) . https://ir.law.fsu.edu/lr/vol3/iss4/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Florida State University Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW VOLUME 3 FALL 1975 NUMBER 4 THE NAVIGABILITY CONCEPT IN THE CIVIL AND COMMON LAW: HISTORICAL DEVELOPMENT, CURRENT IMPORTANCE, AND SOME DOCTRINES THAT DON'T HOLD WATER GLENN J. MACGRADY TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ---------------------------- . ...... ..... ......... 513 II. ROMAN LAW AND THE CIVIL LAW . ........... 515 A. Pre-Roman Legal Conceptions 515 B. Roman Law . .... .. ... 517 1. Rivers ------------------- 519 a. "Public" v. "Private" Rivers --- 519 b. Ownership of a River and Its Submerged Bed..--- 522 c. N avigable R ivers ..........................................- 528 2. Ownership of the Foreshore 530 C. Civil Law Countries: Spain and France--------- ------------- 534 1. Spanish Law----------- 536 2. French Law ----------------------------------------------------------------542 III. ENGLISH COMMON LAw ANTECEDENTS OF AMERICAN DOCTRINE -- --------------- 545 A. -

Guidance Note

Guidance note The Crown Estate – Escheat All general enquiries regarding escheat should be Burges Salmon LLP represents The Crown Estate in relation addressed in the first instance to property which may be subject to escheat to the Crown by email to escheat.queries@ under common law. This note is a brief explanation of this burges-salmon.com or by complex and arcane aspect of our legal system intended post to Escheats, Burges for the guidance of persons who may be affected by or Salmon LLP, One Glass Wharf, interested in such property. It is not a complete exposition Bristol BS2 0ZX. of the law nor a substitute for legal advice. Basic principles English land law has, since feudal times, vested in the joint tenants upon a trust determine the bankrupt’s interest and been based on a system of tenure. A of land. the trustee’s obligations and liabilities freeholder is not an absolute owner but • Freehold property held subject to a trust. with effect from the date of disclaimer. a“tenant in fee simple” holding, in most The property may then become subject Properties which may be subject to escheat cases, directly from the Sovereign, as lord to escheat. within England, Wales and Northern Ireland paramount of all the land in the realm. fall to be dealt with by Burges Salmon LLP • Disclaimer by liquidator Whenever a “tenancy in fee simple”comes on behalf of The Crown Estate, except for In the case of a company which is being to an end, for whatever reason, the land in properties within the County of Cornwall wound up in England and Wales, the liquidator may, by giving the prescribed question may become subject to escheat or the County Palatine of Lancaster. -

Present Legal Estates in Fee Simple

CHAPTER 3 Present Legal Estates in Fee Simple A. THE ENGLISH LAW T THE beginning of the thirteenth century, when the royal courts of justice were acquiring effective A control of the development of private law, the possible forms of action and their limits were uncertain. It seemed then that a new form of action could be de vised to fit any need which might arise. In the course of that century the courts set themselves to limiting the possible forms of action to a definite list, defining with certainty the scope of permitted actions, and so refusing relief upon states of fact which did not fall within the fixed limits of permitted forms of action. This process, of course, operated to fix and limit the classes of private rights protected by law.101 A parallel process went on with respect to interests in land. At the beginning of the thirteenth century, when alienation of land was becoming possible, it seemed that any sort of interest which ingenuity could devise might be created by apt terms in the transfer creating the interest. Perhaps the form of the gift could create interests of any specified duration, with peculiar rules for descent, with special rights not ordinarily in cident to ownership, or deprived of some of the ordinary incidents of ownership. As in the case of the forms of action, the courts set themselves to limiting the possible interests in land to a definite list, defining with certainty 1o1 Maitland, FoRMS OF ACTION AT CoMMON LAW 51-52 (reprint 1941). 37 38 PERPETUITIES AND OTHER RESTRAINTS the incidents of permitted interests, and refusing to en force provisions of a gift which would add to or subtract from the fixed incidents of the type of interest conveyed. -

2021 State of Utah Uniform Fine Schedule

2021 UNIFORM FINE SCHEDULE INTENT It is the intent of the Uniform Fine Schedule to assist the sentencing judge in determining the appropriate fine to be imposed as a condition of the sentence in a particular case and to minimize disparity in sentencing for similar offenses and offenders. This schedule is not intended to supplant or to minimize a court’s authority to impose a just sentence. APPLICABILITY These guidelines shall apply to all courts of record and not of record whenever a criminal fine may be imposed. In determining whether a fine is appropriate to impose as a condition of the sentence for a public offense, a judge should consider several factors, including aggravating and/or mitigating circumstances set forth in the Sentencing And Release Guidelines, Tab 6, the cumulative effect of probation conditions, and the ability of the defendant to pay. The amounts listed in the Uniform Fine Schedule may be used as a starting point for setting monetary bail as a condition of pretrial release, however, an individual’s ability to pay must be considered consistent with Appendix J of the Code of Judicial Administration. In those parking, traffic, and infraction cases where the defendant is not required to appear and is mailed a citation indicating the fine amount, pursuant to Utah Code of Judicial Administration Rule 4-701, the amount may be increased $50 if the defendant fails to appear or to pay within fourteen days after receiving the citation. The amount may be increased by an additional $75 if the defendant fails to appear or to pay within forty days after receiving the citation. -

Law Enforcement & Legal Elements Necessary for Prosecution

Partnership to Combat Critical Infrastructure Copper Theft Webinar Law Enforcement & Legal Elements Necessary for Prosecution February 28, 2012 Roxann M. Ryan, J.D., Ph.D. Iowa Department of Public Safety Division of Intelligence & Fusion Center The theft of copper and other precious metals is hardly new,1 although the targets have changed over time. As copper prices have reached all-time highs, burglars and thieves are accessing new sources of metal. The criminal charges available also have changed over time. In 2011, the Iowa legislature amended two statutes to specifically address the potential risk to public-utility critical infrastructure. What began as House File 299 during the 2011 Iowa legislative session became law on July 1, 2011. That legislation consisted of two primary initiatives: (1) Local ordinances are authorized.2 Municipalities and counties can pass ordinances to require salvage dealers to maintain complete records of their supplies. Failure to comply can result in a suspension or revocation of the salvage dealer’s permit or license. (2) Penalties are increased for trespass on public utility property.3 It is a class “D” felony to trespass on public utility property, which carries a sentence of up to 5 years in prison and a fine of $7500. The options for criminal charges include far more than these two additions. Copper thieves typically commit one or more of the following crimes: Burglary 713.6A. Burglary in the third degree 1. All burglary which is not burglary in the first degree or burglary in the The elements of Burglary are as second degree is burglary in the third degree. -

Official List of Public Waters

Official List of Public Waters New Hampshire Department of Environmental Services Water Division Dam Bureau 29 Hazen Drive PO Box 95 Concord, NH 03302-0095 (603) 271-3406 https://www.des.nh.gov NH Official List of Public Waters Revision Date October 9, 2020 Robert R. Scott, Commissioner Thomas E. O’Donovan, Division Director OFFICIAL LIST OF PUBLIC WATERS Published Pursuant to RSA 271:20 II (effective June 26, 1990) IMPORTANT NOTE: Do not use this list for determining water bodies that are subject to the Comprehensive Shoreland Protection Act (CSPA). The CSPA list is available on the NHDES website. Public waters in New Hampshire are prescribed by common law as great ponds (natural waterbodies of 10 acres or more in size), public rivers and streams, and tidal waters. These common law public waters are held by the State in trust for the people of New Hampshire. The State holds the land underlying great ponds and tidal waters (including tidal rivers) in trust for the people of New Hampshire. Generally, but with some exceptions, private property owners hold title to the land underlying freshwater rivers and streams, and the State has an easement over this land for public purposes. Several New Hampshire statutes further define public waters as including artificial impoundments 10 acres or more in size, solely for the purpose of applying specific statutes. Most artificial impoundments were created by the construction of a dam, but some were created by actions such as dredging or as a result of urbanization (usually due to the effect of road crossings obstructing flow and increased runoff from the surrounding area). -

Duke Environmental Law & Policy Forum

Duke Environmental Law & Policy Forum Spring, 1998 8 Duke Env L & Pol'y F 209 ECONOMIC INCENTIVES AND LEGAL TOOLS FOR PRIVATE SECTOR CONSERVATION Ian Bowles, * David Downes, ** Dana Clark, *** and Marianne Guerin-McManus **** * Vice President and Director of Policy Department, Conservation International. ** Senior Attorney with the Center for International Environmental Law. *** Senior Attorney with the Center for International Environmental Law. **** Director of Conservation Finance Program, Conservation International. SUMMARY: ... At the same time, public concern about environmental issues like clean drinking water, overconsumption of natural resources, and worldwide loss of tropical forests has grown explosively and led policymakers to devote more attention to these issues. ... In most jurisdictions, a conservation easement is created when the landowner transfers some or all rights to develop the property to a government agency or qualified conservation non-governmental organization (NGO); the landowner can maintain certain uses but cannot legally take actions inconsistent with the terms of the conservation easement. ... To encourage donations of conservation easements, a number of jurisdictions specifically provide that a conservation easement qualifies as a charitable contribution, enabling a landowner to deduct its value from her taxable income. ... This provision has proven to be a significant incentive for conservation of biodiversity. ... One method for capturing at least some of the many costs of timber extraction is a user fee. ... Recreation, though not as destructive as extractive resource development, has environmental consequences. ... When a landowner donates a conservation easement, or enters into a conservation agreement, ensure that the landowner's property is taxed at a rate according to its current market value (its value subject to the easement or the agreement), rather than its potential development value. -

The Law of Property

THE LAW OF PROPERTY SUPPLEMENTAL READINGS Class 14 Professor Robert T. Farley, JD/LLM PROPERTY KEYED TO DUKEMINIER/KRIER/ALEXANDER/SCHILL SIXTH EDITION Calvin Massey Professor of Law, University of California, Hastings College of the Law The Emanuel Lo,w Outlines Series /\SPEN PUBLISHERS 76 Ninth Avenue, New York, NY 10011 http://lawschool.aspenpublishers.com 29 CHAPTER 2 FREEHOLD ESTATES ChapterScope ------------------- This chapter examines the freehold estates - the various ways in which people can own land. Here are the most important points in this chapter. ■ The various freehold estates are contemporary adaptations of medieval ideas about land owner ship. Past notions, even when no longer relevant, persist but ought not do so. ■ Estates are rights to present possession of land. An estate in land is a legal construct, something apart fromthe land itself. Estates are abstract, figments of our legal imagination; land is real and tangible. An estate can, and does, travel from person to person, or change its nature or duration, while the landjust sits there, spinning calmly through space. ■ The fee simple absolute is the most important estate. The feesimple absolute is what we normally think of when we think of ownership. A fee simple absolute is capable of enduringforever though, obviously, no single owner of it will last so long. ■ Other estates endure for a lesser time than forever; they are either capable of expiring sooner or will definitely do so. ■ The life estate is a right to possession forthe life of some living person, usually (but not always) the owner of the life estate. It is sure to expire because none of us lives forever. -

STATE of MAINE EXECUTIVE DEPARTMENT STATE PLANNIJ'\G OFFICE 38 STATE HOUSE STATION AUGUSTA, MAINE 043 3 3-003Fi ANGUS S

MAINE STATE LEGISLATURE The following document is provided by the LAW AND LEGISLATIVE DIGITAL LIBRARY at the Maine State Law and Legislative Reference Library http://legislature.maine.gov/lawlib Reproduced from scanned originals with text recognition applied (searchable text may contain some errors and/or omissions) Great Pond Tasl< Force Final Report KF 5570 March 1999 .Z99 Prepared by Maine State Planning Office I 84 ·State Street Augusta, Maine 04333 Acknowledgments The Great Pond Task Force thanks Hank Tyler and Mark DesMeules for the staffing they provided to the Task Force. Aline Lachance provided secretarial support for the Task Force. The Final Report was written by Hank Tyler. Principal editing was done by Mark DesMeules. Those offering additional editorial and layout assistance/input include: Jenny Ruffing Begin and Liz Brown. Kevin Boyle, Jennifer Schuetz and JefferyS. Kahl of the University of Maine prepared the economic study, Great Ponds Play an Integral Role in Maine's Economy. Frank O'Hara of Planning Decisions prepared the Executive Summary. Larry Harwood, Office of GIS, prepared the maps. In particular, the Great Pond Task Force appreciates the effort made by all who participated in the public comment phase of the project. D.D.Tyler donated the artwork of a Common Loon (Gavia immer). Copyright Diana Dee Tyler, 1984. STATE OF MAINE EXECUTIVE DEPARTMENT STATE PLANNIJ'\G OFFICE 38 STATE HOUSE STATION AUGUSTA, MAINE 043 3 3-003fi ANGUS S. KING, JR. EVAN D. RICHERT, AICP GOVERNOR DIRECTOR March 1999 Dear Land & Water Resources Council: Maine citizens have spoken loud and clear to the Great Pond Task Force about the problems confronting Maine's lakes and ponds.