Evaluation of the Wired up Communities Programme

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Additions to CASCAT from Carlisle Archives

Cumbria Archive Service CATALOGUE: new additions August 2021 Carlisle Archive Centre The list below comprises additions to CASCAT from Carlisle Archives from 1 January - 31 July 2021. Ref_No Title Description Date BRA British Records Association Nicholas Whitfield of Alston Moor, yeoman to Ranald Whitfield the son and heir of John Conveyance of messuage and Whitfield of Standerholm, Alston BRA/1/2/1 tenement at Clargill, Alston 7 Feb 1579 Moor, gent. Consideration £21 for Moor a messuage and tenement at Clargill currently in the holding of Thomas Archer Thomas Archer of Alston Moor, yeoman to Nicholas Whitfield of Clargill, Alston Moor, consideration £36 13s 4d for a 20 June BRA/1/2/2 Conveyance of a lease messuage and tenement at 1580 Clargill, rent 10s, which Thomas Archer lately had of the grant of Cuthbert Baynbrigg by a deed dated 22 May 1556 Ranold Whitfield son and heir of John Whitfield of Ranaldholme, Cumberland to William Moore of Heshewell, Northumberland, yeoman. Recites obligation Conveyance of messuage and between John Whitfield and one 16 June BRA/1/2/3 tenement at Clargill, customary William Whitfield of the City of 1587 rent 10s Durham, draper unto the said William Moore dated 13 Feb 1579 for his messuage and tenement, yearly rent 10s at Clargill late in the occupation of Nicholas Whitfield Thomas Moore of Clargill, Alston Moor, yeoman to Thomas Stevenson and John Stevenson of Corby Gates, yeoman. Recites Feb 1578 Nicholas Whitfield of Alston Conveyance of messuage and BRA/1/2/4 Moor, yeoman bargained and sold 1 Jun 1616 tenement at Clargill to Raynold Whitfield son of John Whitfield of Randelholme, gent. -

Altogether Archaeology Dry Burn Enclosure Near Garrigill Cumbria

on behalf of Altogether Archaeology Dry Burn enclosure near Garrigill Cumbria archaeological evaluation report 3236 March 2014 Contents 1. Summary 1 2. Project background 2 3. Landuse, topography and geology 3 4. Historical and archaeological background 3 5. The evaluation trenches 3 6. The artefacts 5 7. Palaeoenvironmental assessment 7 8. Recommendations 9 9. Sources 10 Appendix 1: Data tables 11 Appendix 2: Stratigraphic matrices 15 Figures Figure 1: Site location Figure 2: Trench locations Figure 3: Trench plans and sections Figure 4: Trench 1, looking north Figure 5: Outer ditch F5, looking south Figure 6: Section through outer bank [36], looking south‐east Figure 7: Section through internal bank [F37] of outer ditch, looking north‐west Figure 8: Section through inner ditch F7, looking south Figure 9: Section through outer bank of inner ditch [35], looking east Figure 10: Section through inner bank [34] of inner ditch, looking north‐east Figure 11: Section through internal bank F3, looking north Figure 12: Trench 2, looking south Figure 13: Section through Channel [F19], looking south © Archaeological Services Durham University 2014 Green Lane Durham DH1 3LA tel 0191 334 1121 fax 0191 334 1126 [email protected] www.dur.ac.uk/archaeological.services Dry Burn· near Garrigill· Cumbria· archaeological evaluation· report 3236· March 2014 1. Summary The project 1.1 This report presents the results of an archaeological evaluation undertaken on a possible prehistoric enclosure at Dry Burn near Garrigill, Cumbria. Two trenches and a test pit were excavated on the site. 1.2 The works were commissioned by Altogether Archaeology and conducted by volunteers from Altogether Archaeology with training and supervision provided by Archaeological Services Durham University. -

South Tyne Trail

yg sections with easy going access going easy with sections globe footpaths, quiet roads and cycleways and roads quiet footpaths, 1 35flowers 7 At Dorthgill Falls, the moorland stream Tynehead meadows are a Like many other places, Ash Gill had mines. Close to Ashgill [email protected] The Source to Alston drops suddenly into the South Tyne Valley. riot of yellow in the spring: Force you can see a mine entrance, or ‘level’, remains of storage 561601 01228 tel: 8RR CA4 Carlisle, ¹⁄₂ This is an idyllic spot, with the waterfall early on come the bays and a water race but these are disappearing rapidly due to Bridge, Warwick Mill, Warwick 9 miles 15.5 km approx. Project Countryside Cumbria East curlews framed by a cluster of pines. kingcups and buttercups thoughtless dismantling. 2004 c then the rare globe O On the hill above The Source is a South Tyne gorge, Windshaw flowers can be seen. rocky limestone plain. Here the In spring and summer the wildflowers Later come the purple In the river bed, close to the rain percolates down into limestone are stunning: purple lousewort and meadow cranesbill footbridge, cockle fossils may be caverns before trickling to its orchids abound, yellow splashes of and many other seen like white horse shoes birthplace. Until 2002, The Source pimpernel and tormentil, then, meadow flowers. trotting over the dark limestone. was marked only by an old fence lower down, jewels of mountain post and was easily missed. The pansy and bird’s-eye primrose. from: funding massive sculpture by Gilbert Ward At the foot of Ash Gill, the South The insect-eating butterwort ECCP and Danby Simon Corbett, Val should remedy that. -

Read the Garrigill Conservation Area Character Appraisal

Garrigill Conservation Area Character Appraisal and Management Plan March 2020 Contents 1. Introduction ........................................................................................................ 1 1.1 Background to appraisal ............................................................................ 1 1.2 Adoption and publication ........................................................................... 1 2. Planning Policy Context ..................................................................................... 2 2.1 National Planning Policy ............................................................................ 2 2.2 Local Planning Policy ................................................................................ 3 3. History ................................................................................................................ 6 4. Character Appraisal ........................................................................................... 8 4.1 Designated Heritage Assets ...................................................................... 8 4.2 Character Areas ........................................................................................ 8 4.3 Summary of the character and current condition of the conservation area . ................................................................................................................ 18 4.4 Undesignated Heritage Assets ................................................................ 19 5. Management Plan ........................................................................................... -

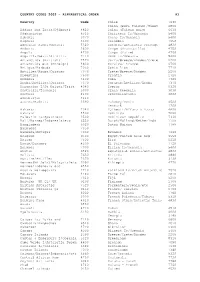

Country Codes 2002 – Alphabetical Order A1

COUNTRY CODES 2002 – ALPHABETICAL ORDER A1 Country Code Chile 7640 China (excl Taiwan)/Tibet 6800 Affars and Issas/Djibouti 4820 China (Taiwan only) 6630 Afghanistan 6510 Christmas Is/Oceania 5400 Albania 3070 Cocos Is/Oceania 5400 Algeria 3500 Colombia 7650 American Samoa/Oceania 5320 Comoros/Antarctic Foreign 4830 Andorra 2800 Congo (Brazzaville) 4750 Angola 4700 Congo (Zaire) 4760 Anguilla/Nevis/St Kitts 7110 Cook Is/Oceania 5400 Antarctica (British) 7520 Corfu/Greece/Rhodes/Crete 2200 Antarctica etc (Foreign) 4830 Corsica/ France 0700 Antigua/Barbuda 7030 Costa Rica 7710 Antilles/Aruba/Curacao 7370 Crete/Greece/Rhodes 2200 Argentina 7600 Croatia 2720 Armenia 3100 Cuba 7320 Aruba/Antilles/Curacao 7370 Curacao/Antilles/Aruba 7370 Ascension I/St Helena/Trist 4040 Cyprus 0320 Australia/Tasmania 5000 Czech Republic 3030 Austria 2100 Czechoslovakia 3020 Azerbaijan 3110 Azores/Madeira 2390 Dahomey/Benin 4500 Denmark 1200 Bahamas 7040 Djibouti/Affars & Issas 4820 Bahrain 5500 Dominica 7080 Balearic Is/Spain/etc 2500 Dominican Republic 7330 Bali/Borneo/Indonesia/etc 6550 Dutch/Holland/Netherlnds 1100 Bangladesh 6020 Dutch Guiana 7780 Barbados 7050 Barbuda/Antigua 7030 Ecuador 7660 Belgium 0500 Egypt/United Arab Rep 3550 Belize 7500 Eire 0210 Benin/Dahomey 4500 El Salvador 7720 Bermuda 7000 Ellice Is/Oceania 5400 Bhutan 6520 Equatorial Guinea/Antarctic 4830 Bolivia 7630 Eritrea 4840 Bonaire/Antilles 7370 Estonia 3130 Borneo(NE Soln)/Malaysia/etc 6050 Ethiopia 4770 Borneo/Indonesia etc 6550 Bosnia Herzegovina 2710 Falkland Is/Brtsh Antarctic -

These Properties Are Listed Buildings; the Full Details (And in Most Cases, A

These properties are Listed buildings; the full details (and in most cases, a photograph) are given in the English Heritage Images of England website and may be seen by clicking on the link shown. A number of items have been excluded such as milestones, walls, gate piers, telephone kiosks. Listed buildings in Alston Moor 1. Bird House to E of Clarghyll Hall 2. Blackstock's Baker's Shop 3. Blue Bell Hotel 4. Church Gates 5. Church of St Augustine 6. Claim Stone in Corner of Field ~1000 Yards NE of Blagillhead Farmhouse 7. Clarghyll Hall 8. Corner House Adjoining S of Blue Bell Hotel 9. Cross View Cottage 10. Gilderdale Bridge (1) 11. Gilderdale Bridge (2), Knaresdale 12. Gilderdale Viaduct 13. Railway Viaduct over the Gilderdale Burn 250m NE of Gilderdale Bridge 14. Gossipgate Bridge to SW of Gossipgate House 15. H Kearton and Sons Store 16. H Kearton's Shops Adjoining W End of Cross View Cottage 17. Harbut Lodge 18. Hillcrest Hotel 19. House Adjoining N End of Monument View 20. House Adjoining S End of Blue Bell Hotel 21. House Adjoining S End of Monument View 22. Library, Town Hall, Trustee Savings Bank 23. Loaning Foot House 24. Garage and Garden Walls to Loaning Foot House 25. Lowbyer Manor Farmhouse 26. Lowbyer Manor Hotel 27. Lyndhurst 28. Market Cross 29. Memorial Pump and Canopy 30. Monument View 31. Number 4, Adjoining N End of Lyndhurst 32. Orchard House 33. Property Adjoining E End of Blackstock's Baker's Shop 34. Property Adjoining E End of Cross View Cottage 35. -

Sense of Place, Engagement with Heritage and Ecomuseum Potential in the North Pennines AONB

INTERNATIONAL CENTRE FOR CULTURAL AND HERITAGE STUDIES SCHOOL OF ARTS AND CULTURES NEWCASTLE UNIVERSITY Sense of Place, Engagement with Heritage and Ecomuseum Potential in the North Pennines AONB Doctor of Philosophy Stephanie Kate Hawke 31 December 2010 Acknowledgements I would like to thank my supervisors, Peter Davis, Gerard Corsane and Peter Samsom. Even before research began, the determination of Peter Davis coupled with Peter Samsom’s infectious enthusiasm propelled the project through uncertain waters. From then, with Gerard’s encouragement, the thesis took shape and throughout its completion I have appreciated beyond measure the easy confidence my supervisory team have expressed in my capability. In particular I am grateful for the generosity with which my supervisors have given their time, with prompt feedback, advice and encouragement. The value of working within a research community at the International Centre for Cultural and Heritage Studies cannot be underestimated and in particular I would like to acknowledge Helen Graham, Rhiannon Mason and Andrew Newman for sharing their thoughts. I have also been lucky to work with a very special group of research students. I have known genuine friendship whilst sharing an office with Nikki Spalding, Tori Park, Sarah Chapman and Susannah Eckersley. Michelle Stefano has encouraged and inspired me in equal measure. It has been a pleasure to share my days with all of the Bruce Building research postgraduates especially Bryony Onciul, Ino Maragoudaki, Eva Chen, Dinç Saraç, Arwa Badran, Justin Sikora and Suzie Thomas. In the North Pennines I am grateful to the people who gave up their time to be interviewed, sharing their thoughts and feelings with such candour. -

The Source to Alston Drops Suddenly Into the South Tyne Valley

sections with easy going access going easy with sections globe footpaths, quiet r quiet footpaths, oads and cycleways and oads 1 35flowers 7 At Dorthgill Falls, the moorland stream Tynehead meadows are a Like many other places, Ash Gill had mines. Close to Ashgill [email protected] The Source to Alston drops suddenly into the South Tyne Valley. riot of yellow in the spring: Force you can see a mine entrance, or ‘level’, remains of storage 561601 01228 tel: 8RR CA4 Carlisle, This is an idyllic spot, with the waterfall early on come the bays and a water race but these are disappearing rapidly due to Bridge, Warwick Mill, Warwick 9¹⁄₂ miles 15.5 km approx. Project Countryside Cumbria East curlews framed by a cluster of pines. kingcups and buttercups thoughtless dismantling. 2004 c then the rare globe O On the hill above The Source is a South Tyne gorge, Windshaw flowers can be seen. rocky limestone plain. Here the In spring and summer the wildflowers Later come the purple In the river bed, close to the rain percolates down into limestone are stunning: purple lousewort and meadow cranesbill footbridge, cockle fossils may be caverns before trickling to its orchids abound, yellow splashes of and many other seen like white horse shoes birthplace. Until 2002, The Source pimpernel and tormentil, then, meadow flowers. trotting over the dark limestone. was marked only by an old fence lower down, jewels of mountain post and was easily missed. The pansy and bird’s-eye primrose. from: funding massive sculpture by Gilbert Ward At the foot of Ash Gill, the South The insect-eating butterwort ECCP and Danby Simon Corbett, Val should remedy that. -

Nurture Eden Doorstep Guide to Garrigill

NURTURE EDEN DOORSTEP GUIDE TO GARRIGILL SPONSORED BY ISAAC’s BYRE ECO-FRIENDLY COTTAGE Welcome to Isaac’s Byre in As well as all this, just north of Isaac’s Isaac’s Byre is at Loaning Head, Garrigill, based in the North Byre is Alston, England’s highest pronounced ‘Lonnin’ Head’ in market town, reaching heady heights Cumbrian dialect. Pennines and Alston Moor. of around 1000ft above sea level You’re in a unique part of (London is on average about 79ft). the country that held strong There’s plenty to see and do on your importance to Romans and doorstep so read on about some of the Miners, and which is now local gems to discover and give your the meeting point between car a break too. the iconic Pennine Trail and the cycling Coast to Coast ride, as well as the Rivers South Tyne, Wear and Tees. Isaac’s Byre To Alston and the B6277 Loaning River South Tyne Head GARRIGILL Footpath from Isaac’s Byre to the Village Rose Cottage Studio and Gallery George and Garrigill Dragon Pub Bridge St John’s Pool Garrigill Post Office HigZiX]ndjgaZ\hVcYZmeadgZ l]ViÉhdcndjgYddghiZe### NURTURE EDEN DOORSTEP GUIDE TO GARRIGILL SPONSORED BY ISAAC’s BYRE ECO-FRIENDLY COTTAGE ST JOHN’s POOL ALSTON MOOR GOLF COURSE Unwind and enjoy this little indoor oasis in Don’t worry if you’ve forgotten your clubs; the middle of Garrigill village. The pool go for a walk or a picnic on the highest is available for private hire, and comes golf course in England, possibly the UK. -

Alston Cycle Route

PUBLIC TRANSPORT INFORMATION Traveline Tel: 0870 608 2 608 Cycling Web: www.traveline.org.uk IN THE TOURIST INFORMATION CENTRES NORTH PENNINES Alston - The Town Hall The North Pennines is one of Tel: 01434 382244 routes for England’s most special places - Penrith a peaceful, unspoilt landscape Tel: 01768 867466 experienced cyclists with a rich history and vibrant 4 natural beauty. It was designated FURTHER INFORMATION on and off road For more information about the North as an Area of Outstanding starting from ALSTON Pennines contact the AONB Staff Unit Natural Beauty in 1988. Tel: 01388 528801 The AONB is also a UNESCO Email: [email protected] Global Geopark. River Allen Web: www.northpennines.org.uk (Northumberland County Council) An excellent way of exploring the North Pennines is by bike. This They are designed as a series of circular routes and one figure- g❂❂d cycling code . leaflet describes four routes of various of-eight off-road route - all starting from Alston. They link to Please follow this simple code to ensure enjoyable riding lengths that can be started from the Sea to Sea (C2C) Cycle Route. and the safety of others. ❂ Alston. Route 1 is very tough due to the numerous steep hills, however Obey the rules of the road Follow the Countryside Code. ❂ Follow the Highway Code Respect. Protect. Enjoy. Visit www.countrysideaccess.gov.uk Other leaflets in this series cover the terrain in the North Pennines means that it is impossible Be courteous to avoid some steep climbs and so few routes are easy. ❂ Give way to pedestrians and Look after yourself routes from Allendale Town, horse riders. -

An Account of the Mining Districts of Alston Moor, Weardale And

'"''s^^- , M^ CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY THE WORDSWORTH COLLECTION FOUNDED BY CYNTHIA MORGAN ST. JOHN THE GIFT OF VICTOR EMANUEL OF THE CLASS OF I919 &7D y\\ Cornell University Library The original of tiiis book is in tine Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924104090695 or THE I'mxcirAi aoads &•<• MINING DISTRICTS^ of . and the ailjoiiiing<lales NORTH MID I ir a OT TO n K S H 1 H K 20JEle — # AN ACCOUNT OF THE MINING DISTRICTS OF ALSTON MOOR, WEARDALE, AND TEESDALE, IN COMPRISIIfG DESCRIPTIVE SKETCHES OF THE SCENERY, ANTIQUITIES, GEOLOGY, AND MINING OPERATIONS, IN THE UPPER DALES OF THE RIVERS TYNE, WEAR, AND TEES. BY T. SOPWITH, LAND AND MINE SURVEYOR, ALNWICK: PRINTED BY AND FOR W. DAVISON. SOLD ALSO BY THE BOOKSELLERS IN NORTHUMBKK LAND, DURHAM, CUMBERLAND, &c. MDCCCXXXIII. 1-. % u%A/ PREFACE. The Lead-Mining Districts of the north of England comprise an extensive range of highly picturesque scenery, which is rendered still more interesting by numerous objects which claim the attention of the antiquary, the geologist, and the mineralogist, and, in short, of all who delight in the combined attractions of nature, science, and art. Of these districts no detailed account has been given to the public; and a famihar description of the northern lead-mines, in which so many persons in this part of the kingdom are concerned, has long been a desideratum in local literature. The present volume aspires not to the merit of supplying this want; but, by descriptive notices of the principal objects of attraction, is intended to convey some general ideas of the nature of the lead-mining districts, and to afford some information which may serve as a guide to those who visit them. -

(Public Pack)Agenda Document For

Date: 11 March 2020 Town Hall, Penrith, Cumbria CA11 7QF Tel: 01768 817817 Email: [email protected] Dear Sir/Madam Planning Committee Agenda - 19 March 2020 Notice is hereby given that a meeting of the Planning Committee will be held at 9.30 am on Thursday, 19 March 2020 at the Council Chamber, Town Hall, Penrith. 1 Apologies for Absence 2 Minutes To sign the minutes: 1) Pla/125/02/20 to Pla/138/02/20 of the meeting of this Committee held on 13 February 2020; and 2) Pla/139/02/20 to Pla/144/02/20 of the site visit meeting of this Committee held on 27 February 2020 as a correct record of those proceedings (copies previously circulated). 3 Declarations of Interest To receive any declarations of the existence and nature of any private interests, both disclosable pecuniary and any other registrable interests, in any matter to be considered or being considered. 4 Appeal Decision Letters (Pages 7 - 14) To receive report PP13/20 from the Assistant Director Planning and Economic Development which is attached and which lists decision letters from the Planning Inspectorate received since the last meeting: Application Applicant/Appeal Appeal Decision No. 19/0219 Mr Metcalfe The appeal is Land adjacent to Hillside, Ruckcroft, allowed and Carlisle, CA4 9QR planning permission granted The appeal is made under section subject to 78 of the Town and Country conditions. Rose Rouse Chief Executive www.eden.gov.uk Planning Act 1990 against a refusal to grant outline planning permission. The development proposed is described as ‘outline consent for a single dwelling’.