LD120 North Pennines AONB Management Plan 2009-2014

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Norman Rule Cumbria 1 0

NORMAN RULE I N C U M B R I A 1 0 9 2 – 1 1 3 6 B y RICHARD SHARPE A lecture delivered to Cumberland and Westmorland Antiquarian and Archaeological Society on 9th April 2005 at Carlisle CUMBERLAND AND WESTMORLAND ANTIQUARIAN AND ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY N O R M A N R U L E I N C U M B R I A 1 0 9 2 – 1 1 3 6 NORMAN RULE I N C U M B R I A 1 0 9 2 – 1 1 3 6 B y RICHARD SHARPE Pr o f essor of Diplomat i c , U n i v e r sity of Oxfo r d President of the Surtees Society A lecture delivered to Cumberland and Westmorland Antiquarian and Archaeological Society on 9th April 2005 at Carlisle CUMBERLAND AND WESTMORLAND ANTIQUARIAN AND ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY Tract Series Vol. XXI C&W TRACT SERIES No. XXI ISBN 1 873124 43 0 Published 2006 Acknowledgements I am grateful to the Council of the Society for inviting me, as president of the Surtees Society, to address the Annual General Meeting in Carlisle on 9 April 2005. Several of those who heard the paper on that occasion have also read the full text and allowed me to benefit from their comments; my thanks to Keith Stringer, John Todd, and Angus Winchester. I am particularly indebted to Hugh Doherty for much discussion during the preparation of this paper and for several references that I should otherwise have missed. In particular he should be credited with rediscovering the writ-charter of Henry I cited in n. -

2010 Club Experience - Cheap Weekend Walking Breaks Enjoy the High Pennines, Hadrian’S Wall & Durham on Our Annual Short Summer Break

“Outdoor activities for all” 2010 Club Experience - Cheap Weekend Walking Breaks Enjoy the High Pennines, Hadrian’s Wall & Durham on our annual Short Summer Break Thursday 1st to Monday 5th July 2010 John Hillaby’s Journey through Britain: “No botanical name-dropping, can give an adequate impression of the botanical jewels sprinkled on the ground above High Force. In this valley, a tundra has been marvellously preserved; the glint of colour, the reds, deep purples, and blues have the quality of Chartres glass.” High Force Booking Information & Form High England – Hadrian’s Wall and The North Pennines, a designated Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty, for much of its history a wild and dangerous frontier zone until the union of the crowns in 1603 largely ended centuries of war with Scotland. Today, it is sadly an area often overlooked by walkers as we head further north to the mountains of Scotland or to the Lake District. On our Club Experience summer short breaks we seek remoteness, the lure of hills, trails and paths to suit all abilities, places of culture and history and a destination that can enable us to escape for a short while from the stress of work and enjoy the social fun and community we all crave. Blackton Grange www.blacktongrangefarmhouse.com I promise will surprise - surrounded by rolling uplands, quiet lanes, dry stone walls and scenic reservoirs it is the perfect destination to escape the hustle and bustle and enjoy a relaxing break, with the comforts of home in a spectacular setting. This great venue can sleep up to 45 persons, but for our club experience long weekend the maximum number accommodated will be 28 persons, giving us a minimum of 6 double/twin rooms available and no more than four persons will share the other spacious bedrooms (these shared rooms will be allocated on a single sex basis unless booked by couples or friends who may wish to share). -

New Additions to CASCAT from Carlisle Archives

Cumbria Archive Service CATALOGUE: new additions August 2021 Carlisle Archive Centre The list below comprises additions to CASCAT from Carlisle Archives from 1 January - 31 July 2021. Ref_No Title Description Date BRA British Records Association Nicholas Whitfield of Alston Moor, yeoman to Ranald Whitfield the son and heir of John Conveyance of messuage and Whitfield of Standerholm, Alston BRA/1/2/1 tenement at Clargill, Alston 7 Feb 1579 Moor, gent. Consideration £21 for Moor a messuage and tenement at Clargill currently in the holding of Thomas Archer Thomas Archer of Alston Moor, yeoman to Nicholas Whitfield of Clargill, Alston Moor, consideration £36 13s 4d for a 20 June BRA/1/2/2 Conveyance of a lease messuage and tenement at 1580 Clargill, rent 10s, which Thomas Archer lately had of the grant of Cuthbert Baynbrigg by a deed dated 22 May 1556 Ranold Whitfield son and heir of John Whitfield of Ranaldholme, Cumberland to William Moore of Heshewell, Northumberland, yeoman. Recites obligation Conveyance of messuage and between John Whitfield and one 16 June BRA/1/2/3 tenement at Clargill, customary William Whitfield of the City of 1587 rent 10s Durham, draper unto the said William Moore dated 13 Feb 1579 for his messuage and tenement, yearly rent 10s at Clargill late in the occupation of Nicholas Whitfield Thomas Moore of Clargill, Alston Moor, yeoman to Thomas Stevenson and John Stevenson of Corby Gates, yeoman. Recites Feb 1578 Nicholas Whitfield of Alston Conveyance of messuage and BRA/1/2/4 Moor, yeoman bargained and sold 1 Jun 1616 tenement at Clargill to Raynold Whitfield son of John Whitfield of Randelholme, gent. -

826 INDEX 1066 Country Walk 195 AA La Ronde

© Lonely Planet Publications 826 Index 1066 Country Walk 195 animals 85-7, see also birds, individual Cecil Higgins Art Gallery 266 ABBREVIATIONS animals Cheltenham Art Gallery & Museum A ACT Australian Capital books 86 256 A La RondeTerritory 378 internet resources 85 City Museum & Art Gallery 332 abbeys,NSW see New churches South & cathedrals Wales aquariums Dali Universe 127 Abbotsbury,NT Northern 311 Territory Aquarium of the Lakes 709 FACT 680 accommodationQld Queensland 787-90, 791, see Blue Planet Aquarium 674 Ferens Art Gallery 616 alsoSA individualSouth locations Australia Blue Reef Aquarium (Newquay) Graves Gallery 590 activitiesTas 790-2,Tasmania see also individual 401 Guildhall Art Gallery 123 activitiesVic Victoria Blue Reef Aquarium (Portsmouth) Hayward Gallery 127 AintreeWA FestivalWestern 683 Australia INDEX 286 Hereford Museum & Art Gallery 563 air travel Brighton Sea Life Centre 207 Hove Museum & Art Gallery 207 airlines 804 Deep, The 615 Ikon Gallery 534 airports 803-4 London Aquarium 127 Institute of Contemporary Art 118 tickets 804 National Marine Aquarium 384 Keswick Museum & Art Gallery 726 to/from England 803-5 National Sea Life Centre 534 Kettle’s Yard 433 within England 806 Oceanarium 299 Lady Lever Art Gallery 689 Albert Dock 680-1 Sea Life Centre & Marine Laing Art Gallery 749 Aldeburgh 453-5 Sanctuary 638 Leeds Art Gallery 594-5 Alfred the Great 37 archaeological sites, see also Roman Lowry 660 statues 239, 279 sites Manchester Art Gallery 658 All Souls College 228-9 Avebury 326-9, 327, 9 Mercer Art Gallery -

The Journal of the Fell & Rock Climbing Club

THE JOURNAL OF THE FELL & ROCK CLIMBING CLUB OF THE ENGLISH LAKE DISTRICT Edited by W. G. STEVENS No. 47 VOLUME XVI (No. Ill) Published bt THE FELL AND ROCK CLIMBING CLUB OF THE ENGLISH LAKE DISTRICT 1953 CONTENTS PAGE The Mount Everest Expedition of 1953 ... Peter Lloyd 215 The Days of our Youth ... ... ...Graham Wilson 217 Middle Alps for Middle Years Dorothy E. Pilley Richards 225 Birkness ... ... ... ... F. H. F. Simpson 237 Return to the Himalaya ... T. H. Tilly and /. A. ]ac\son 242 A Little More than a Walk ... ... Arthur Robinson 253 Sarmiento and So On ... ... D. H. Maling 259 Inside Information ... ... ... A. H. Griffin 269 A Pennine Farm ... ... ... ... Walter Annis 275 Bicycle Mountaineering ... ... Donald Atkinson 278 Climbs Old and New A. R. Dolphin 284 Kinlochewe, June, 1952 R. T. Wilson 293 In Memoriam ... ... ... ... ... ... 296 E. H. P. Scantlebury O. J. Slater G. S. Bower G. R. West J. C. Woodsend The Year with the Club Muriel Files 303 Annual Dinner, 1952 A. H. Griffin 307 'The President, 1952-53 ' John Hirst 310 Editor's Notes ... ... ... ... ... ... 311 Correspondence ... ... ... ... ... ... 315 London Section, 1952 316 The Library ... ... ... ... ... ... 318 Reviews ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 319 THE MOUNT EVEREST EXPEDITION OF 1953 — AN APPRECIATION Peter Lloyd Everest has been climbed and the great adventure which was started in 1921 has at last been completed. No climber can fail to have been thrilled by the event, which has now been acclaimed by the nation as a whole and honoured by the Sovereign, and to the Fell and Rock Club with its long association with Everest expeditions there is especial reason for pride and joy in the achievement. -

Appleby & Dufton

Vol: 31 Issue 5 7th May 2017 APPLEBY & DUFTON Coach leaves Appleby at 5.00pm and Dufton at 5.30pm. The first drop-off stop will be Black Bull PROGRAMME OF EVENTS May 2017 11 May Thursday Car – Yarrow Valley 10.30am start - Sat Nav: PR7 3QL Map Ref: GR570153 B: Allan Benson Meet at Birkacre Visitor Centre 17 May Stroller – Longton 10.30am start - Sat Nav: PR4 5HA S: Joan & Allan Meet at the Rams Head car park, then Rams Head Pub 21 May Sunday Car B: Tockholes 10.30am start - Sat Nav: BB3 0PA Dorothy Dobson Meet at Tockholes Information Centre car park C: Edgworth Reservoirs 10.30am start - Sat Nav: BL7 0AP Map Ref: GR 742166 Margaret & Bob Meet c.park behind "The Barlow" Building next door to cricket club June 2017 4 June Coach – Great Langdale 8.00am start – Return 5.30pm – first drop-off Black Bull A: Crinkle Crags & Bowfell Leader : Dave Colbert B+: Stickle Tarn Leader: Val Walmsley B: Lingmoor Fell Leader: Colin Manning C: Elterwater Circular Leader: Joyce Bradbury Thursday Car – Yarrow Valley – 11 May 8 miles (12.9km) with no significant climbing Leader: Allan Benson Meet at Birkacre Visitor Centre (Sat Nav: PR7 3QL Map Ref: GR570153), ready for the usual start time of 10.30am. We start our walk from the country park and follow the River Yarrow through Saunders Bank and Big Wood to Duxbury Park. We then follow the Leeds Liverpool Canal for approximat ely 2 miles before making our way back to Yarrow Park via Sandy Lane, footpaths and some quiet roads. -

Altogether Archaeology Dry Burn Enclosure Near Garrigill Cumbria

on behalf of Altogether Archaeology Dry Burn enclosure near Garrigill Cumbria archaeological evaluation report 3236 March 2014 Contents 1. Summary 1 2. Project background 2 3. Landuse, topography and geology 3 4. Historical and archaeological background 3 5. The evaluation trenches 3 6. The artefacts 5 7. Palaeoenvironmental assessment 7 8. Recommendations 9 9. Sources 10 Appendix 1: Data tables 11 Appendix 2: Stratigraphic matrices 15 Figures Figure 1: Site location Figure 2: Trench locations Figure 3: Trench plans and sections Figure 4: Trench 1, looking north Figure 5: Outer ditch F5, looking south Figure 6: Section through outer bank [36], looking south‐east Figure 7: Section through internal bank [F37] of outer ditch, looking north‐west Figure 8: Section through inner ditch F7, looking south Figure 9: Section through outer bank of inner ditch [35], looking east Figure 10: Section through inner bank [34] of inner ditch, looking north‐east Figure 11: Section through internal bank F3, looking north Figure 12: Trench 2, looking south Figure 13: Section through Channel [F19], looking south © Archaeological Services Durham University 2014 Green Lane Durham DH1 3LA tel 0191 334 1121 fax 0191 334 1126 [email protected] www.dur.ac.uk/archaeological.services Dry Burn· near Garrigill· Cumbria· archaeological evaluation· report 3236· March 2014 1. Summary The project 1.1 This report presents the results of an archaeological evaluation undertaken on a possible prehistoric enclosure at Dry Burn near Garrigill, Cumbria. Two trenches and a test pit were excavated on the site. 1.2 The works were commissioned by Altogether Archaeology and conducted by volunteers from Altogether Archaeology with training and supervision provided by Archaeological Services Durham University. -

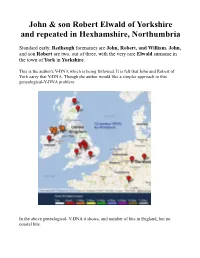

John & Son Robert Elwald of Yorkshire and Repeated in Hexhamshire

John & son Robert Elwald of Yorkshire and repeated in Hexhamshire, Northumbria Standard early, Redheugh forenames are John, Robert, and William. John, and son Robert are two, out of three, with the very rare Elwald surname in the town of York in Yorkshire. This is the author's Y-DNA which is being followed. It is felt that John and Robert of York carry that Y-DNA. Though the author would like a simpler approach to this genealogical-Y-DNA problem. In the above genealogical- Y-DNA it shows, and number of hits in England, but no coastal hits. It should be noted that York is near Wolds (woods), as apposed to the Moors (moorland). Note the location of Scarborough; Hexham north part of map. The first name translated as Johannes (John), and the middle name Johannesen (Johnson (son of John)). So it is in Norway, the name John was held in high, and also surname Walde, for Elwalde is importand. Both German and Danish seem to prefix wald (woods). Elwald surname emerged not as a location such as Scarborough, but as being the son of (fitz) Elwald. It is felt that John and his son Robert could easily carry similar Y- DNA out of the Northumberland, region of York. As one can see above Johannes Elwald mercator quam. This shows, how both Johnannes and Elwald could have strong origins in Denmark German. The name Robert had strong influence after 1320 because of Robert the Bruce, who the Elwald fought for in the separation of the crowns of Scotland and England. -

HADRIAN HUNDRED 25Th - 27Th MAY 2019

HADRIAN HUNDRED 25th - 27th MAY 2019 REGISTRATION – QUEEN ELIZABETH HIGH SCHOOL, HEXHAM NY 926 639 Welcome to Hexham once the haunt of marauding Vikings but now England’s favourite market town with the imposing Abbey at its hub. Starting in Northumberland the route visits Cumbria and Durham before returning to Northumberland for the later stages. Highlights include sections on Hadrian’s Wall, the South Tyne Trail, the Pennine Way (with Cross Fell and High Cup Nick), the Weardale Way and Isaac’s Tea Trail. Abbreviations TR Turn Right TL Turn Left N, S North, South etc. XXXm,Xkm Approx. distance in metres or kilometres to next feature (XXXdeg) Approx. magnetic bearing in degrees to next feature Units Convention Stage Summaries Miles & Kilometres (Distance), Feet & Metres (Ascent) Descriptive Text Metres (m) & Kilometres (km) NB. 100 metres = 109 yards 1 Kilometre = 0.62 miles Please note that all measurements of distance and ascent are produced from a GPS device which gives good estimates only therefore great accuracy cannot be guaranteed. 1 Important Notes A significant proportion of the Route uses or crosses roads, the vast majority of which are very minor and little used. The modern approach to Risk Assessment, however, requires that the risks involved in potentially mixing foot and vehicular traffic are pointed out whenever this happens. It is not proposed to mention this on every occasion that it occurs in the Route Description narrative. When a road is used or crossed the appropriate description will be highlighted. Additional warnings will be given whenever more major roads are encountered. Please be vigilant on roads especially later in the Event as you become increasingly tired and possibly less attentive. -

A Lithostratigraphical Framework for the Carboniferous Successions of Northern Great Britain (Onshore)

A lithostratigraphical framework for the Carboniferous successions of northern Great Britain (onshore) Research Report RR/10/07 HOW TO NAVIGATE THIS DOCUMENT Bookmarks The main elements of the table of contents are bookmarked enabling direct links to be followed to the principal section headings and sub- headings, figures, plates and tables irrespective of which part of the document the user is viewing. In addition, the report contains links: from the principal section and subsection headings back to the contents page, from each reference to a figure, plate or table directly to the corresponding figure, plate or table, from each figure, plate or table caption to the first place that figure, plate or table is mentioned in the text and from each page number back to the contents page. RETURN TO CONTENTS PAGE BRITISH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY The National Grid and other Ordnance Survey data are used RESEARCH REPOrt RR/10/07 with the permission of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office. Licence No: 100017897/2011. Keywords Carboniferous, northern Britain, lithostratigraphy, chronostratigraphy, biostratigraphy. A lithostratigraphical framework Front cover for the Carboniferous successions View of Kae Heughs, Garleton Hills, East Lothian. Showing of northern Great Britain Chadian to Arundian lavas and tuffs of the Garleton Hills Volcanic Formation (Strathclyde Group) (onshore) exposed in a prominent scarp (P001032). Bibliographical reference M T Dean, M A E Browne, C N Waters and J H Powell DEAN, M T, BROWNE, M A E, WATERS, C N, and POWELL, J H. 2011. A lithostratigraphical Contributors: M C Akhurst, S D G Campbell, R A Hughes, E W Johnson, framework for the Carboniferous N S Jones, D J D Lawrence, M McCormac, A A McMillan, D Millward, successions of northern Great Britain (Onshore). -

South Tyne Trail

yg sections with easy going access going easy with sections globe footpaths, quiet roads and cycleways and roads quiet footpaths, 1 35flowers 7 At Dorthgill Falls, the moorland stream Tynehead meadows are a Like many other places, Ash Gill had mines. Close to Ashgill [email protected] The Source to Alston drops suddenly into the South Tyne Valley. riot of yellow in the spring: Force you can see a mine entrance, or ‘level’, remains of storage 561601 01228 tel: 8RR CA4 Carlisle, ¹⁄₂ This is an idyllic spot, with the waterfall early on come the bays and a water race but these are disappearing rapidly due to Bridge, Warwick Mill, Warwick 9 miles 15.5 km approx. Project Countryside Cumbria East curlews framed by a cluster of pines. kingcups and buttercups thoughtless dismantling. 2004 c then the rare globe O On the hill above The Source is a South Tyne gorge, Windshaw flowers can be seen. rocky limestone plain. Here the In spring and summer the wildflowers Later come the purple In the river bed, close to the rain percolates down into limestone are stunning: purple lousewort and meadow cranesbill footbridge, cockle fossils may be caverns before trickling to its orchids abound, yellow splashes of and many other seen like white horse shoes birthplace. Until 2002, The Source pimpernel and tormentil, then, meadow flowers. trotting over the dark limestone. was marked only by an old fence lower down, jewels of mountain post and was easily missed. The pansy and bird’s-eye primrose. from: funding massive sculpture by Gilbert Ward At the foot of Ash Gill, the South The insect-eating butterwort ECCP and Danby Simon Corbett, Val should remedy that. -

Read the Garrigill Conservation Area Character Appraisal

Garrigill Conservation Area Character Appraisal and Management Plan March 2020 Contents 1. Introduction ........................................................................................................ 1 1.1 Background to appraisal ............................................................................ 1 1.2 Adoption and publication ........................................................................... 1 2. Planning Policy Context ..................................................................................... 2 2.1 National Planning Policy ............................................................................ 2 2.2 Local Planning Policy ................................................................................ 3 3. History ................................................................................................................ 6 4. Character Appraisal ........................................................................................... 8 4.1 Designated Heritage Assets ...................................................................... 8 4.2 Character Areas ........................................................................................ 8 4.3 Summary of the character and current condition of the conservation area . ................................................................................................................ 18 4.4 Undesignated Heritage Assets ................................................................ 19 5. Management Plan ...........................................................................................