Vampires and Sexual Identity in Laurell K. Hamilton's An/7A Bl4/Ce

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Dracula Film Adaptations

DRACULA IN THE DARK DRACULA IN THE DARK The Dracula Film Adaptations JAMES CRAIG HOLTE Contributions to the Study of Science Fiction and Fantasy, Number 73 Donald Palumbo, Series Adviser GREENWOOD PRESS Westport, Connecticut • London Recent Titles in Contributions to the Study of Science Fiction and Fantasy Robbe-Grillet and the Fantastic: A Collection of Essays Virginia Harger-Grinling and Tony Chadwick, editors The Dystopian Impulse in Modern Literature: Fiction as Social Criticism M. Keith Booker The Company of Camelot: Arthurian Characters in Romance and Fantasy Charlotte Spivack and Roberta Lynne Staples Science Fiction Fandom Joe Sanders, editor Philip K. Dick: Contemporary Critical Interpretations Samuel J. Umland, editor Lord Dunsany: Master of the Anglo-Irish Imagination S. T. Joshi Modes of the Fantastic: Selected Essays from the Twelfth International Conference on the Fantastic in the Arts Robert A. Latham and Robert A. Collins, editors Functions of the Fantastic: Selected Essays from the Thirteenth International Conference on the Fantastic in the Arts Joe Sanders, editor Cosmic Engineers: A Study of Hard Science Fiction Gary Westfahl The Fantastic Sublime: Romanticism and Transcendence in Nineteenth-Century Children’s Fantasy Literature David Sandner Visions of the Fantastic: Selected Essays from the Fifteenth International Conference on the Fantastic in the Arts Allienne R. Becker, editor The Dark Fantastic: Selected Essays from the Ninth International Conference on the Fantastic in the Arts C. W. Sullivan III, editor Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Holte, James Craig. Dracula in the dark : the Dracula film adaptations / James Craig Holte. p. cm.—(Contributions to the study of science fiction and fantasy, ISSN 0193–6875 ; no. -

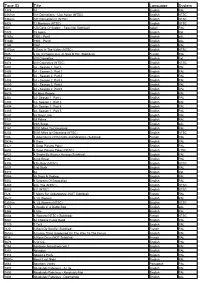

Malcolm's Video Collection

Malcolm's Video Collection Movie Title Type Format 007 A View to a Kill Action VHS 007 A View To A Kill Action DVD 007 Casino Royale Action Blu-ray 007 Casino Royale Action DVD 007 Diamonds Are Forever Action DVD 007 Diamonds Are Forever Action DVD 007 Diamonds Are Forever Action Blu-ray 007 Die Another Day Action DVD 007 Die Another Day Action Blu-ray 007 Dr. No Action VHS 007 Dr. No Action Blu-ray 007 Dr. No DVD Action DVD 007 For Your Eyes Only Action DVD 007 For Your Eyes Only Action VHS 007 From Russia With Love Action VHS 007 From Russia With Love Action Blu-ray 007 From Russia With Love DVD Action DVD 007 Golden Eye (2 copies) Action VHS 007 Goldeneye Action Blu-ray 007 GoldFinger Action Blu-ray 007 Goldfinger Action VHS 007 Goldfinger DVD Action DVD 007 License to Kill Action VHS 007 License To Kill Action Blu-ray 007 Live And Let Die Action DVD 007 Never Say Never Again Action VHS 007 Never Say Never Again Action DVD 007 Octopussy Action VHS Saturday, March 13, 2021 Page 1 of 82 Movie Title Type Format 007 Octopussy Action DVD 007 On Her Majesty's Secret Service Action DVD 007 Quantum Of Solace Action DVD 007 Quantum Of Solace Action Blu-ray 007 Skyfall Action Blu-ray 007 SkyFall Action Blu-ray 007 Spectre Action Blu-ray 007 The Living Daylights Action VHS 007 The Living Daylights Action Blu-ray 007 The Man With The Golden Gun Action DVD 007 The Spy Who Loved Me Action Blu-ray 007 The Spy Who Loved Me Action VHS 007 The World Is Not Enough Action Blu-ray 007 The World is Not Enough Action DVD 007 Thunderball Action Blu-ray 007 -

Tales from the Crypt

Ah, HBO. Here in the year 2014, those three little initials are shorthand for quality, original programming; small screen event television almost certain to be immeasurably superior to the megabucks offerings of your local multiplex. The network also boasts a rich tradition of brining monsters into our living rooms, with the unsavoury actions of Livia Soprano, Gyp Rosetti, Cy Tolliver and Joffrey Baratheon horrifying viewers of all walks of life. Way back in the late 1980s, however, HBO introduced us to an altogether different kind of miscreant; a wisecracking living corpse, a teller of tall tales that focussed on vampires, zombies and the evil that men do. Jackanory it most certainly wasn’t – we’re referring, of course, to the legendary Tales from the Crypt. In the 80s, TV anthology horror was as much a fixture as leg warmers, John Hughes movies and the musical stylings of Duran Duran. Rod Serling’s Twilight Zone had enjoyed a redux, James Coburn invited us to his Darkroom, a certain pizza-faced dream demon hosted Freddy’s Nightmares, and genre enthusiasts were gripped by the Ray Bradbury Theater. Perhaps the most prosperous purveyor of small screen shivers was producer Richard Rubinstein, who enjoyed phenomenal success with Tales from the Darkside (the brainchild of none other than George Romero, director of the beloved portmanteau picture Creepshow) and Monsters. Bright and breezy 30-minute creature features with their tongue frequently placed firmly in their cheek, these shows were heavily influenced by the infamous EC horror comics of the 1950s, with a perverse sense of morality at the dark heart of the stories. -

Buffy at Play: Tricksters, Deconstruction, and Chaos

BUFFY AT PLAY: TRICKSTERS, DECONSTRUCTION, AND CHAOS AT WORK IN THE WHEDONVERSE by Brita Marie Graham A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in English MONTANA STATE UNIVERSTIY Bozeman, Montana April 2007 © COPYRIGHT by Brita Marie Graham 2007 All Rights Reserved ii APPROVAL Of a thesis submitted by Brita Marie Graham This thesis has been read by each member of the thesis committee and has been found to be satisfactory regarding content, English usage, format, citations, bibliographic style, and consistency, and is ready for submission to the Division of Graduate Education. Dr. Linda Karell, Committee Chair Approved for the Department of English Dr. Linda Karell, Department Head Approved for the Division of Graduate Education Dr. Carl A. Fox, Vice Provost iii STATEMENT OF PERMISSION TO USE In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a master’s degree at Montana State University, I agree that the Library shall make it availably to borrowers under rules of the Library. If I have indicated my intention to copyright this thesis by including a copyright notice page, copying is allowable only for scholarly purposes, consistent with “fair use” as prescribed in the U.S. Copyright Law. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this thesis in whole or in parts may be granted only by the copyright holder. Brita Marie Graham April 2007 iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS In gratitude, I wish to acknowledge all of the exceptional faculty members of Montana State University’s English Department, who encouraged me along the way and promoted my desire to pursue a graduate degree. -

Tape ID Title Language System

Tape ID Title Language System 1375 10 English PAL 0361sn 101 Dalmatians - Live Action (NTSC) English NTSC 0362sn 101 Dalmatians II (NTSC) English NTSC 6826 12 Monkeys (NTSC) English NTSC i031 120 Days Of Sodom - Salo (Not Subtitled) Italian PAL 1078 18 Again English Pal 5163a 1900 - Part I English pAL 5163b 1900 - Part II English pAL 1244 1941 English PAL 0172sn 2 Days In The Valley (NTSC) English NTSC f085 2 Ou 3 Choses Que Je Sais D Elle (Subtitled) French PAL 1304 200 Cigarettes English Pal 6474 200 Cigarettes (NTSC) English NTSC 2401 24 - Season 1, Vol 1 English PAL 2406 24 - Season 2, Part 1 English PAL 2407 24 - Season 2, Part 2 English PAL 2408 24 - Season 2, Part 3 English PAL 2409 24 - Season 2, Part 4 English PAL 2410 24 - Season 2, Part 5 English PAL 5675 24 Hour People English PAL 2402 24- Season 1, Part 2 English PAL 2403 24- Season 1, Part 3 English PAL 2404 24- Season 1, Part 4 English PAL 2405 24- Season 1, Part 5 English PAL 3287 28 Days Later English PAL 5731 29 Palms English PAL 5501 29th Street English pAL 3141 3000 Miles To Graceland English PAL 6234 3000 Miles to Graceland (NTSC) English NTSC f103 4 Adventures Of Reinette and Mirabelle (Subtitled) French PAL 0514s 4 Days English PAL 3421 4 Dogs Playing Poker English PAL 6607 4 Dogs Playing Poker (NTSC) English nTSC g033 4 Shorts By Werner Herzog (Subtitled) English PAL 0160 42nd Street English PAL 6306 4Th Floor (NTSC) English NTSC 3437 51st State English PAL 5310 54 English Pal 0058 55 Days At Peking English PAL 3052 6 Degrees Of Separation English PAL 6389 60s, The (NTSC) English NTSC 6555 61* (NTSC) English NTSC f126 7 Morts Sur Ordonnance (NOT Subtitled) French PAL 5623 8 1/2 Women English PAL 0253sn 8 1/2 Women (NTSC) English NTSC 1175 8 Heads In A Duffel Bag English pAL 5344 8 Mile English PAL 6088 8 Women (NTSC) (Subtitled) French NTSC 5041 84 Charing Cross Road English PAL 1129 9 To 5 English PAL f220 A Bout De Souffle (Subtitled) French PAL 0652s A Funny Thing Happened On The Way To The Forum English PAL f018 A Nous Deux (NOT Subtitled) French PAL 3676 A.W.O.L. -

Ballots Finally Counted Safety and Security

Red lifter C ► mmuoity ('allege September 3 - September 15 , 1996 Issue 4 Photo a no- go By Kim Babij News Editor RCC students are going to nhave to wait a little longer to see themselves in pictures. Photo ID cards that had been proposed for the fall of 1996 won't be a reality for at least one more year, and maybe more. "What we originally thought would be a simple project has ended up being much more corn- plicated," said Dean of Student Affairs Fausto Yadao. According to Yadao, until a photo ID system that is compati- ble with the College's current security system is found, the Students bask in what we hope won't be the last of this summer's heat. cards won't be feasible. As well, the photo ID cards, similar to the ones in use at the in the budget with which we can College. "We're looking into it for the University of Manitoba, could respond to the project," he said. Yadao said a number of meet- '97 school year," said Yadao. cost anywhere from $25,000 - As it stands, students are ings have been held to discuss "We would like to build the S45,000, a price that's a tad too issued a pictureless card with possibilities for the project, funds into the budget as there high for the College. their name, student number and a including suppliers of cards, have been recommendations that "Right now there are no funds black bar code that allows them what kind of system could be this is a project with merit." access to various areas of the used, as well as a source of funds. -

Bordello of Blood Wiki

Bordello of blood wiki Bordello of Blood is a horror comedy film starring Dennis Miller, Erika Eleniak, Angie Everhart, Corey Feldman and Chris Sarandon. It is based on the HBO Box office: $ million (US). Comedy · The Crypt Keeper returns to tell the story of a funeral parlor that moonlights as a vampire bordello. Bordello of Blood (also known as Tales from the Crypt Presents: Bordello of Blood) is a comedy/horror film starring Dennis Miller, Erika Eleniak, Angie. Tamara was a minor villainess from the horror/comedy Tales from the Crypt Presents: Bordello of Blood. She was played by Kiara Hunter. Tamara (called. Lilith is the main antagonist of the horror/comedy film, Tales from the Crypt Presents: Bordello of Blood. She is played by Angie Everhart. Lilith (Bordello of Blood) - the queen of the vampires and the main antagonist from the movie. Tales from the Crypt Presents: Bordello of Blood () Director: Gilbert Adler. returns to tell the story of a funeral parlor that moonlights as a vampire bordello. Tamara (Kiara Hunter) was a minor villainess from the film, Tales from the Crypt Presents: Bordello of Blood. Tamara is first shown being interviewed for a. Tales from the Crypt: Bordello of Blood is an American horror film directed by Bordello of Blood at Wikipedia · Bordello of Blood at · Bordello of. Reverend Jimmy "J.C." Current is a supporting antagonist in the horror/comedy film Tales from the Crypt Presents: Bordello of Blood. He is portrayed by. File:Tales from the Crypt - Bordello of Size of this preview: × pixels. Full resolution (download) ( × pixels, file size: 39 KB, MIME type. -

De Los Libros a La Gran Pantalla Hizkia Filmatua: Liburutik Pantaila Handira

La letra filmada: del libro a la gran pantalla Hizkia filmatua: liburutik pantaila handira The word on film: from the paper to the silver screen La letra filmada: de los libros a la gran pantalla Desde el 23 de abril Hizkia filmatua: liburutik pantaila handira Apirilaren 23-tik aurrera ARTIUM- Arte Garaikideko Euskal Zentro-Museoa - Centro-Museo Vasco de Arte Contemporáneo 1 Liburutegi eta Dokumentazio Saila / Departamento de Biblioteca y Documentación Francia, 24 - 01002 Vitoria-Gasteiz. Tf.945-209000 http://www.artium.org/biblioteca.html La letra filmada: del libro a la gran pantalla Hizkia filmatua: liburutik pantaila handira The word on film: from the paper to the silver screen ARTIUM- Arte Garaikideko Euskal Zentro-Museoa - Centro-Museo Vasco de Arte Contemporáneo 2 Liburutegi eta Dokumentazio Saila / Departamento de Biblioteca y Documentación Francia, 24 - 01002 Vitoria-Gasteiz. Tf.945-209000 http://www.artium.org/biblioteca.html La letra filmada: del libro a la gran pantalla Hizkia filmatua: liburutik pantaila handira The word on film: from the paper to the silver screen INTRODUCCIÓN ARTIUM- Arte Garaikideko Euskal Zentro-Museoa - Centro-Museo Vasco de Arte Contemporáneo 3 Liburutegi eta Dokumentazio Saila / Departamento de Biblioteca y Documentación Francia, 24 - 01002 Vitoria-Gasteiz. Tf.945-209000 http://www.artium.org/biblioteca.html La letra filmada: del libro a la gran pantalla Hizkia filmatua: liburutik pantaila handira The word on film: from the paper to the silver screen LA LETRA FILMADA: DEL LIBRO A LA GRAN PANTALLA Una nueva exposición bibliográfica nos introduce en esta ocasión en el apasionante mundo del cine a través de una selección de más de 150 adaptaciones cinematográficas de la literatura universal. -

Gothic—Film—Parody1

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Lancaster E-Prints Gothic—Film—Parody1 Kamilla Elliott Department of English and Creative Writing, Lancaster University, United Kingdom [email protected] Abstract: Gothic, film, and parody are all erstwhile devalued aesthetic forms recuperated by various late twentieth-century humanities theories, serving in return as proof-texts for these theories in their battles against formalism, high-art humanism, and right-wing politics. Gothic film parodies parody these theories as well as Gothic fiction and films. As they redouble Gothic doubles, refake Gothic fakeries, and critique Gothic criticism, they go beyond simple mockery to reveal inconsistencies, incongruities, and problems in Gothic criticism: boundaries that it has been unwilling or unable to blur, binary oppositions it has refused to deconstruct, like those between left- and right-wing politics, and points at which a radical, innovative, subversive discourse manifests as its own hegemonic, dogmatic, and clichéd double, as in critical manipulations of Gothic (dis)belief. The discussion engages Gothic film parodies spanning a range of decades (from the 1930s to the 2000s) and genres (from feature films to cartoons to pornographic parodies). Keywords: Gothic; film; parody; literary film adaptation; criticism; theory; psychoanalysis; identity politics; belief; We laugh at the structures which had in the past formed the appearance of inviolable 1 truth. Today’s laughter is the movement from the laughter of the past. —Sander L. Gilman (23) The hyphens in the title are part homage to, part parody of Roland Barthes’s Image— Music—Text. -

DVD Laser Disc Newsletter DVD Reviews Complete Index June 2008

DVD Laser Disc Newsletter DVD Reviews Complete Index June 2008 Title Issue Page *batteries not included May 99 12 "10" Jun 97 5 "Weird Al" Yankovic: The Videos Feb 98 15 'Burbs Jun 99 14 1 Giant Leap Nov 02 14 10 Things I Hate about You Apr 00 10 100 Girls by Bunny Yaeger Feb 99 18 100 Rifles Jul 07 8 100 Years of Horror May 98 20 1000 Eyes of Dr. Mabuse Sep 00 2 101 Dalmatians Jan 00 14 101 Dalmatians Apr 08 11 101 Dalmatians (remake) Jun 98 10 101 Dalmatians II Patch's London Adventure May 03 15 10:30 P.M. Summer Sep 07 6 10th Kingdom Jul 00 15 11th Hour May 08 10 11th of September Moyers in Conversation Jun 02 11 12 Monkeys May 98 14 12 Monkeys (DTS) May 99 8 123 Count with Me Jan 00 15 13 Ghosts Oct 01 4 13 Going on 30 Aug 04 4 13th Warrior Mar 00 5 15 Minutes Sep 01 9 16 Blocks Jul 07 3 1776 Sep 02 3 187 May 00 12 1900 Feb 07 1 1941 May 99 2 1942 A Love Story Oct 02 5 1962 Newport Jazz Festival Feb 04 13 1979 Cotton Bowl Notre Dame vs. Houston Jan 05 18 1984 Jun 03 7 1998 Olympic Winter Games Figure Skating Competit May 99 7 1998 Olympic Winter Games Figure Skating Exhib. Sep 98 13 1998 Olympic Winter Games Hockey Highlights May 99 7 1998 Olympic Winter Games Overall Highlights May 99 7 2 Fast 2 Furious Jan 04 2 2 Movies China 9 Liberty 287/Gone with the West Jul 07 4 Page 1 All back issues are available at $5 each or 12 issues for $47.50. -

Trio of Terror Lyz Reblin

e-Research: A Journal of Undergraduate Work Volume 2 Article 6 Number 1 Vol 2, No 1 (2011) September 2014 Trio of Terror Lyz Reblin Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.chapman.edu/e-Research Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons Recommended Citation Reblin, Lyz (2014) "Trio of Terror," e-Research: A Journal of Undergraduate Work: Vol. 2: No. 1, Article 6. Available at: http://digitalcommons.chapman.edu/e-Research/vol2/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Chapman University Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in e-Research: A Journal of Undergraduate Work by an authorized administrator of Chapman University Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Reblin: Trio of Terror Trio of Terror e-Research: A Journal of Undergraduate Work, Vol 2, No 1 (2011) HOME ABOUT LOGIN REGISTER SEARCH CURRENT ARCHIVES Home > Vol 2, No 1 (2011) > Reblin Trio of Terror Lyz Reblin Key words, concepts, and names: Nosferatu, Dracula, Vampyr, Vampire, Horror. Intro From the earliest silent films such as Georges Méliès' The Devil's Castle (1896) to the recent Twilight adaptation, the vampire genre, like the creatures it presents, has been resurrected throughout cinematic history. More than a hundred vampire films have been produced, along with over a dozen Dracula adaptations. The Count has even appeared in films not pertaining to Bram Stoker's original novel. He has been played by the likes of Bela Lugosi, Christopher Lee (fourteen times) both John and David Carradine, and even Academy Award winner Gary Oldman. -

Meredith Zamsky

GILBERT ADLER PRODUCER FEATURES BUCKLEY’S CHANCE (Producer) Buff Dubs Prod: Tim Brown, Scott Clayton, Dir: Tim Brown Andrew Mann DYLAN DOG: DEAD OF NIGHT (Producer) Hyde Park Entertainment Prod: Ashok Amritraj, Scott Rosenberg Dir: Kevin Munroe VALKYRIE (Producer) MGM/United Artists Prod: Christopher MacQuarrie, Bryan Singer Dir: Bryan Singer SUPERMAN RETURNS (Producer) Warner Bros. Prod: Jon Peters Dir: Bryan Singer CONSTANTINE (Executive Producer) Warner Bros. Prod: Lauren Shuler Donner, Dir: Francis Lawrence Lorenzo di Bonaventura STARSKY & HUTCH (Executive Producer) Warner Bros. Prod: Stuart Cornfeld, Ben Stiller Dir: Todd Phillips GHOST SHIP (Producer) Warner Bros. Prod: Joel Silver, Robert Zemeckis Dir: Steve Beck THIRTEEN GHOSTS (Producer) Warner Bros. Prod: Joel Silver, Robert Zemeckis Dir: Steve Beck HOUSE ON HAUNTED HILL Warner Bros. Prod: Joel Silver, Robert Zemeckis Dir: William Malone (Producer) DOUBLE TAP (Producer) HBO Films Prod: Richard Donner, Joel Silver Dir: Greg Yaitanes BORDELLO OF BLOOD Universal Pictures Prod: Joel Silver, Robert Zemeckis Dir: Gilbert Adler (Producer & Writer) TALES FROM THE CRYPT: Universal Pictures Prod: Joel Silver, Robert Zemeckis Dir: Ernest Dickerson DEMON KNIGHT (Producer) BASIC TRAINING (Producer) MGM Studios Prod: Paul Klein, Lawrence Vanger Dir: Andrew Sugerman TELEVISION INTELLIGENCE (Season 1) ABC Studios/CBS Prod: Michael Seitzman, Tripp Vinson Dir: David Semel (Producer) THE STRIP (Season 1) Warner Bros./UPN Prod: Joel Silver, Ken Horton Dir: Various (Co-Executive Producer) TALES FROM THE CRYPT (Season 3-7) HBO Prod: Joel Silver, Robert Zemeckis Dir: Various (93 Episodes) (Producer, Writer & Director) W.E.I.R.D WORLD (MOW) Hallmark/FOX Prod: Joel Silver, Robert Zemeckis Dir: William Malone (Executive Producer) FREDDY’S NIGHTMARES (Season 1-2) New Line/ .