Tales from the Crypt

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tese De Charles Ponte

UNIVERSIDADE ESTADUAL DE CAMPINAS INSTITUTO DE ESTUDOS DA LINGUAGEM CHARLES ALBUQUERQUE PONTE INDÚSTRIA CULTURAL, REPETIÇÃO E TOTALIZAÇÃO NA TRILOGIA PÂNICO Tese apresentada ao Instituto de Estudos da Linguagem, da Universidade Estadual de Campinas, para obtenção do Título de Doutor em Teoria e História Literária, na área de concentração de Literatura e Outras Produções Culturais. Orientador: Prof. Dr. Fabio Akcelrud Durão CAMPINAS 2011 i FICHA CATALOGRÁFICA ELABORADA POR CRISLLENE QUEIROZ CUSTODIO – CRB8/8624 - BIBLIOTECA DO INSTITUTO DE ESTUDOS DA LINGUAGEM - UNICAMP Ponte, Charles, 1976- P777i Indústria cultural, repetição e totalização na trilogia Pânico / Charles Albuquerque Ponte. -- Campinas, SP : [s.n.], 2011. Orientador : Fabio Akcelrud Durão. Tese (doutorado) - Universidade Estadual de Campinas, Instituto de Estudos da Linguagem. 1. Craven, Wes. Pânico - Crítica e interpretação. 2. Indústria cultural. 3. Repetição no cinema. 4. Filmes de horror. I. Durão, Fábio Akcelrud, 1969-. II. Universidade Estadual de Campinas. Instituto de Estudos da Linguagem. III. Título. Informações para Biblioteca Digital Título em inglês: Culture industry, repetition and totalization in the Scream trilogy. Palavras-chave em inglês: Craven, Wes. Scream - Criticism and interpretation Culture industry Repetition in motion pictures Horror films Área de concentração: Literatura e Outras Produções Culturais. Titulação: Doutor em Teoria e História Literária. Banca examinadora: Fabio Akcelrud Durão [Orientador] Lourdes Bernardes Gonçalves Marcio Renato Pinheiro -

Starlog Magazine Issue

23 YEARS EXPLORING SCIENCE FICTION ^ GOLDFINGER s Jjr . Golden Girl: Tests RicklBerfnanJponders Er_ her mettle MimilMif-lM ]puTtism!i?i ff?™ § m I rifbrm The Mail Service Hold Mail Authorization Please stop mail for: Name Date to Stop Mail Address A. B. Please resume normal Please stop mail until I return. [~J I | undelivered delivery, and deliver all held I will pick up all here. mail. mail, on the date written Date to Resume Delivery Customer Signature Official Use Only Date Received Lot Number Clerk Delivery Route Number Carrier If option A is selected please fill out below: Date to Resume Delivery of Mail Note to Carrier: All undelivered mail has been picked up. Official Signature Only COMPLIMENTS OF THE STAR OCEAN GAME DEVEL0PER5. YOU'RE GOING TO BE AWHILE. bad there's Too no "indefinite date" box to check an impact on the course of the game. on those post office forms. Since you have no Even your emotions determine the fate of your idea when you'll be returning. Everything you do in this journey. You may choose to be romantically linked with game will have an impact on the way the journey ends. another character, or you may choose to remain friends. If it ever does. But no matter what, it will affect your path. And more You start on a quest that begins at the edge of the seriously, if a friend dies in battle, you'll feel incredible universe. And ends -well, that's entirely up to you. Every rage that will cause you to fight with even more furious single person you _ combat moves. -

Malcolm's Video Collection

Malcolm's Video Collection Movie Title Type Format 007 A View to a Kill Action VHS 007 A View To A Kill Action DVD 007 Casino Royale Action Blu-ray 007 Casino Royale Action DVD 007 Diamonds Are Forever Action DVD 007 Diamonds Are Forever Action DVD 007 Diamonds Are Forever Action Blu-ray 007 Die Another Day Action DVD 007 Die Another Day Action Blu-ray 007 Dr. No Action VHS 007 Dr. No Action Blu-ray 007 Dr. No DVD Action DVD 007 For Your Eyes Only Action DVD 007 For Your Eyes Only Action VHS 007 From Russia With Love Action VHS 007 From Russia With Love Action Blu-ray 007 From Russia With Love DVD Action DVD 007 Golden Eye (2 copies) Action VHS 007 Goldeneye Action Blu-ray 007 GoldFinger Action Blu-ray 007 Goldfinger Action VHS 007 Goldfinger DVD Action DVD 007 License to Kill Action VHS 007 License To Kill Action Blu-ray 007 Live And Let Die Action DVD 007 Never Say Never Again Action VHS 007 Never Say Never Again Action DVD 007 Octopussy Action VHS Saturday, March 13, 2021 Page 1 of 82 Movie Title Type Format 007 Octopussy Action DVD 007 On Her Majesty's Secret Service Action DVD 007 Quantum Of Solace Action DVD 007 Quantum Of Solace Action Blu-ray 007 Skyfall Action Blu-ray 007 SkyFall Action Blu-ray 007 Spectre Action Blu-ray 007 The Living Daylights Action VHS 007 The Living Daylights Action Blu-ray 007 The Man With The Golden Gun Action DVD 007 The Spy Who Loved Me Action Blu-ray 007 The Spy Who Loved Me Action VHS 007 The World Is Not Enough Action Blu-ray 007 The World is Not Enough Action DVD 007 Thunderball Action Blu-ray 007 -

Ernest Farino

Ernest Farino Biography & Résumé Frank Herbert’s Dune 2nd Unit Director Ernest Farino Direc tor, Writer DGA (404) 771-3589 [email protected] ERNEST FARINO Director (DGA) / Writer Ernest Farino has directed three feature fi lms, 7 hours of television, and extensive 2nd Unit (including not only action sequences but full scenes with principal actors). His most recent assignment was an episode of the SyFy/ Netfl ix series Superstition starring Mario Van Peebles and Robinne Lee. His episode of the syndicated series Monsters, “Mannikins of Horror,” Steel and Lace based on a story by Robert (Psycho) Bloch, was touted as the top episode Director of the premiere season. Farino then directed the premiere episode of the second season with Lydia Cornell and Marc McClure, as well as episodes Steel and Lace starring Orson Bean, Ed Marinaro and Tina Louise. Director (with Brian Backer and Clare Wren) The Monsters episodes lead Farino to directing the feature fi lm, Steel and Lace (Fries Entertainment) starring Bruce Davison (Oscar® nominee for Longtime Companion), Clare Wren (The Young Riders), David Naughton (An American Werewolf in London) and Michael Cerveris (Tony nominee as Tommy in The Who’s Tommy on Broadway and recent co-star of The Good Wife) and written by Emmy® winner Joseph Dougherty. Following its theatrical release, Steel and Lace recouped over $1 million in foreign sales on its fi rst offering, had an initial pre-buy of 20,000 video units, was released on laserdisc, and has played extensively on Pay-Per-View, HBO, Cinemax, The Movie Channel and Showtime. “Steel and Lace is a cool, inventive take on the revenge thriller … the Pulp Fiction of its time. -

Reminder List of Productions Eligible for the 86Th Academy Awards

REMINDER LIST OF PRODUCTIONS ELIGIBLE FOR THE 86TH ACADEMY AWARDS ABOUT TIME Notes Domhnall Gleeson. Rachel McAdams. Bill Nighy. Tom Hollander. Lindsay Duncan. Margot Robbie. Lydia Wilson. Richard Cordery. Joshua McGuire. Tom Hughes. Vanessa Kirby. Will Merrick. Lisa Eichhorn. Clemmie Dugdale. Harry Hadden-Paton. Mitchell Mullen. Jenny Rainsford. Natasha Powell. Mark Healy. Ben Benson. Philip Voss. Tom Godwin. Pal Aron. Catherine Steadman. Andrew Martin Yates. Charlie Barnes. Verity Fullerton. Veronica Owings. Olivia Konten. Sarah Heller. Jaiden Dervish. Jacob Francis. Jago Freud. Ollie Phillips. Sophie Pond. Sophie Brown. Molly Seymour. Matilda Sturridge. Tom Stourton. Rebecca Chew. Jon West. Graham Richard Howgego. Kerrie Liane Studholme. Ken Hazeldine. Barbar Gough. Jon Boden. Charlie Curtis. ADMISSION Tina Fey. Paul Rudd. Michael Sheen. Wallace Shawn. Nat Wolff. Lily Tomlin. Gloria Reuben. Olek Krupa. Sonya Walger. Christopher Evan Welch. Travaris Meeks-Spears. Ann Harada. Ben Levin. Daniel Joseph Levy. Maggie Keenan-Bolger. Elaine Kussack. Michael Genadry. Juliet Brett. John Brodsky. Camille Branton. Sarita Choudhury. Ken Barnett. Travis Bratten. Tanisha Long. Nadia Alexander. Karen Pham. Rob Campbell. Roby Sobieski. Lauren Anne Schaffel. Brian Charles Johnson. Lipica Shah. Jarod Einsohn. Caliaf St. Aubyn. Zita-Ann Geoffroy. Laura Jordan. Sarah Quinn. Jason Blaj. Zachary Unger. Lisa Emery. Mihran Shlougian. Lynne Taylor. Brian d'Arcy James. Leigha Handcock. David Simins. Brad Wilson. Ryan McCarty. Krishna Choudhary. Ricky Jones. Thomas Merckens. Alan Robert Southworth. ADORE Naomi Watts. Robin Wright. Xavier Samuel. James Frecheville. Sophie Lowe. Jessica Tovey. Ben Mendelsohn. Gary Sweet. Alyson Standen. Skye Sutherland. Sarah Henderson. Isaac Cocking. Brody Mathers. Alice Roberts. Charlee Thomas. Drew Fairley. Rowan Witt. Sally Cahill. -

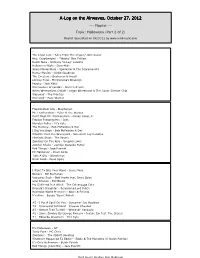

A-Log on the Airwaves, October 27, 2012

A-Log on the Airwaves, October 27, 2012 --- Playlist --- Topic: Halloween (Part 2 of 2) Playlist Generated on 09/27/21 by www.madmusic.com - The Crypt Jam - Tales From The Crypt f/ John Kassir Hey, Cryptkeeper! - "Wacky" Ben Pulliam Death Note - Anthony "A-Log" LoGatto Halloween Night - Dino-Mike Scary Movies Rule - Spookster & The Scaremenots Horror Movies - Dickie Goodman The Creature - Buchanan & Ancell Looney Tune - Montezuma's Revenge Psycho - Jack Kittel Werewolves of London - Warren Zevon When Werewolves Collide - Logan Whitehurst & The Junior Science Club Werewolf - The Frantics Werewolf - Gary Warren - Frankenstein Life - Blaydeman Mr. Frankenstein - Peter & The Wolves Don't Meet Mr. Frankenstein - Carlos Casal, Jr. Frankie Frankenstein - Ivan Monster Polka - TV's Kyle The Mummy - Bob McFadden & Dor I Dig You Baby - Bob McFadden & Dor Whistlin' Past The Graveyard - Screamin' Jay Hawkins Midnight Stroll - The Revels Zombies On The Rise - Gregory Lions Zombie Shake - Zombie Bazooka Patrol Bad Things - Jace Everett PC Halloween - Devo Spice Take A Bite - Blaydeman Brain Food - Devo Spice - I Want To Bite Your Hand - Gene Moss Beware - Bill Buchanan Vampires Suck - Odd Austin feat. Devo Spice Soul Dracula - Hot Blood My Girlfriend Is A Witch - The Cattanooga Cats Dracula's Daughter - Screaming Lord Sutch Hexorcist World Premiere - Albee & Friends It's Alive - Bobby "Boris" Pickett - #5 - I Put A Spell On You - Screamin' Jay Hawkins #4 - Graveyard Girlfriend - Groovie Ghoulies #3 - Nature Trail To Hell - "Weird Al" Yankovic #2 - Some Zombie By George Romero - Insane Ian feat. The Stacey #1 - Eduardo O'Lantern - TV's Kyle - It's Halloween - GT Tasty Face - MC Chris Zombies! - The Abbott Skelding Whatever Happened To Eddie? - Eddie & The Monsters (f/ Butch Patrick) It's Only Halloween - Butch Patrick Bad Things (Club Mix) - Jace Everett Next week: Election Day Madness! Listing added by: A-Log *** Still streaming and still free since 2005 ***. -

(Books): Dark Tower (Comics/Graphic

STEPHEN KING BOOKS: 11/22/63: HB, PB, pb, CD Audiobook 1922: PB American Vampire (Comics 1-5): Apt Pupil: PB Bachman Books: HB, pb Bag of Bones: HB, pb Bare Bones: Conversations on Terror with Stephen King: HB Bazaar of Bad Dreams: HB Billy Summers: HB Black House: HB, pb Blaze: (Richard Bachman) HB, pb, CD Audiobook Blockade Billy: HB, CD Audiobook Body: PB Carrie: HB, pb Cell: HB, PB Charlie the Choo-Choo: HB Christine: HB, pb Colorado Kid: pb, CD Audiobook Creepshow: Cujo: HB, pb Cycle of the Werewolf: PB Danse Macabre: HB, PB, pb, CD Audiobook Dark Half: HB, PB, pb Dark Man (Blue or Red Cover): DARK TOWER (BOOKS): Dark Tower I: The Gunslinger: PB, pb Dark Tower II: The Drawing Of Three: PB, pb Dark Tower III: The Waste Lands: PB, pb Dark Tower IV: Wizard & Glass: PB, PB, pb Dark Tower V: The Wolves Of Calla: HB, pb Dark Tower VI: Song Of Susannah: HB, PB, pb, pb, CD Audiobook Dark Tower VII: The Dark Tower: HB, PB, CD Audiobook Dark Tower: The Wind Through The Keyhole: HB, PB DARK TOWER (COMICS/GRAPHIC NOVELS): Dark Tower: The Gunslinger Born Graphic Novel HB, Comics 1-7 of 7 Dark Tower: The Gunslinger Born ‘2nd Printing Variant’ Comic 1 Dark Tower: The Long Road Home: Graphic Novel HB (x2) & Comics 1-5 of 5 Dark Tower: Treachery: Graphic Novel HB, Comics 1–6 of 6 Dark Tower: Treachery: ‘Midnight Opening Variant’ Comic 1 Dark Tower: The Fall of Gilead: Graphic Novel HB Dark Tower: Battle of Jericho Hill: Graphic Novel HB, Comics 2, 3, 5 of 5 Dark Tower: Gunslinger 1 – The Journey Begins: Comics 2 - 5 of 5 Dark Tower: Gunslinger 1 – -

Media Approved

Film and Video Labelling Body Media Approved Video Titles Title Rating Source Time Date Format Applicant Point of Sales Approved Director Cuts 10,000 B.C. (2 Disc Special Edition) M Contains medium level violence FVLB 105.00 28/09/2010 DVD The Warehouse Roland Emmerich No cut noted Slick Yes 28/09/2010 18 Year Old Russians Love Anal R18 Contains explicit sex scenes OFLC 125.43 21/09/2010 DVD Calvista NZ Ltd Max Schneider No cut noted Slick Yes 21/09/2010 28 Days Later R16 Contains violence,offensive language and horror FVLB 113.00 22/09/2010 Blu-ray Roadshow Entertainment Danny Boyle No cut noted Awaiting POS No 27/09/2010 4.3.2.1 R16 Contains violence,offensive language and sex scenes FVLB 111.55 22/09/2010 DVD Universal Pictures Video Noel Clarke/Mark Davis No cut noted 633 Squadron G FVLB 91.00 28/09/2010 DVD The Warehouse Walter E Grauman No cut noted Slick Yes 28/09/2010 7 Hungry Nurses R18 Contains explicit sex scenes OFLC 99.17 08/09/2010 DVD Calvista NZ Ltd Thierry Golyo No cut noted Slick Yes 08/09/2010 8 1/2 Women R18 Contains sexual references FVLB 120.00 15/09/2010 DVD Vendetta Films Peter Greenaway No cut noted Slick Yes 15/09/2010 AC/DC Highway to Hell A Classic Album Under Review PG Contains coarse language FVLB 78.00 07/09/2010 DVD Vendetta Films Not Stated No cut noted Slick Yes 07/09/2010 Accidents Happen M Contains drug use and offensive language FVLB 88.00 13/09/2010 DVD Roadshow Entertainment Andrew Lancaster No cut noted Slick Yes 13/09/2010 Acting Shakespeare Ian McKellen PG FVLB 86.00 02/09/2010 DVD Roadshow Entertainment -

HBO: Brand Management and Subscriber Aggregation: 1972-2007

1 HBO: Brand Management and Subscriber Aggregation: 1972-2007 Submitted by Gareth Andrew James to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English, January 2011. This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. ........................................ 2 Abstract The thesis offers a revised institutional history of US cable network Home Box Office that expands on its under-examined identity as a monthly subscriber service from 1972 to 1994. This is used to better explain extensive discussions of HBO‟s rebranding from 1995 to 2007 around high-quality original content and experimentation with new media platforms. The first half of the thesis particularly expands on HBO‟s origins and early identity as part of publisher Time Inc. from 1972 to 1988, before examining how this affected the network‟s programming strategies as part of global conglomerate Time Warner from 1989 to 1994. Within this, evidence of ongoing processes for aggregating subscribers, or packaging multiple entertainment attractions around stable production cycles, are identified as defining HBO‟s promotion of general monthly value over rivals. Arguing that these specific exhibition and production strategies are glossed over in existing HBO scholarship as a result of an over-valuing of post-1995 examples of „quality‟ television, their ongoing importance to the network‟s contemporary management of its brand across media platforms is mapped over distinctions from rivals to 2007. -

In the Sorcerer Role-Playing Game, the Characters Are People, Not Mutants Or Monsters, Or Elves

How far will you go to get what you want? In the Sorcerer role-playing game, the characters are people, not mutants or monsters, or elves. However, they are driven people, willing to break the most fundamental laws of reality to achieve their goals. They know how to summon, bind, and command demons. But demons are dangerous, transgressive beings, who demand a Price for the power they lend … mind of its own. Can you handle it? A complete role-playing system. Story creation. This is your instrument. Its rules are built powerful, entertaining story possible. No wasted motion. innovative dice system, well-suited to all aspects of interaction, violence, and sorcery. Flexibility and creativity. Full guidelines permit you to customize the premise into your own, unique vision. winning awards, breaking new ground, showcasing success in independent publishing, and setting standards for clear and effective design, Sorcerer is the same as it always was - a game for today. You’ve never seen role-playing like this before. SORCERER by Ron Edwards The Annotated Sorcerer by Ron Edwards An Intense Role-Playing Game by Ron Edwards Greg Pryor ADEPT PRESS chicago The Annotated Sorcerer Copyright © 2001 by Ron Edwards Copyright Notice All rights reserved. Annotations Copyright © 2012-2013 by Ron Edwards This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the Art Credits US Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without Cover Art by Thomas Denmark written permission from the publisher. -

Cinemeducation Movies Have Long Been Utilized to Highlight Varied

Cinemeducation Movies have long been utilized to highlight varied areas in the field of psychiatry, including the role of the psychiatrist, issues in medical ethics, and the stigma toward people with mental illness. Furthermore, courses designed to teach psychopathology to trainees have traditionally used examples from art and literature to emphasize major teaching points. The integration of creative methods to teach psychiatry residents is essential as course directors are met with the challenge of captivating trainees with increasing demands on time and resources. Teachers must continue to strive to create learning environments that give residents opportunities to apply, analyze, synthesize, and evaluate information (1). To reach this goal, the use of film for teaching may have advantages over traditional didactics. Films are efficient, as they present a controlled patient scenario that can be used repeatedly from year to year. Psychiatry residency curricula that have incorporated viewing contemporary films were found to be useful and enjoyable pertaining to the field of psychiatry in general (2) as well as specific issues within psychiatry, such as acculturation (3). The construction of a formal movie club has also been shown to be a novel way to teach psychiatry residents various aspects of psychiatry (4). Introducing REDRUMTM Building on Kalra et al. (4), we created REDRUMTM (Reviewing [Mental] Disorders with a Reverent Understanding of the Macabre), a Psychopathology curriculum for PGY-1 and -2 residents at Rutgers Robert Wood Johnson Medical School. REDRUMTM teaches topics in mental illnesses by use of the horror genre. We chose this genre in part because of its immense popularity; the tropes that are portrayed resonate with people at an unconscious level. -

Completeandleft

MEN WOMEN 1. JA Jason Aldean=American singer=188,534=33 Julia Alexandratou=Model, singer and actress=129,945=69 Jin Akanishi=Singer-songwriter, actor, voice actor, Julie Anne+San+Jose=Filipino actress and radio host=31,926=197 singer=67,087=129 John Abraham=Film actor=118,346=54 Julie Andrews=Actress, singer, author=55,954=162 Jensen Ackles=American actor=453,578=10 Julie Adams=American actress=54,598=166 Jonas Armstrong=Irish, Actor=20,732=288 Jenny Agutter=British film and television actress=72,810=122 COMPLETEandLEFT Jessica Alba=actress=893,599=3 JA,Jack Anderson Jaimie Alexander=Actress=59,371=151 JA,James Agee June Allyson=Actress=28,006=290 JA,James Arness Jennifer Aniston=American actress=1,005,243=2 JA,Jane Austen Julia Ann=American pornographic actress=47,874=184 JA,Jean Arthur Judy Ann+Santos=Filipino, Actress=39,619=212 JA,Jennifer Aniston Jean Arthur=Actress=45,356=192 JA,Jessica Alba JA,Joan Van Ark Jane Asher=Actress, author=53,663=168 …….. JA,Joan of Arc José González JA,John Adams Janelle Monáe JA,John Amos Joseph Arthur JA,John Astin James Arthur JA,John James Audubon Jann Arden JA,John Quincy Adams Jessica Andrews JA,Jon Anderson John Anderson JA,Julie Andrews Jefferson Airplane JA,June Allyson Jane's Addiction Jacob ,Abbott ,Author ,Franconia Stories Jim ,Abbott ,Baseball ,One-handed MLB pitcher John ,Abbott ,Actor ,The Woman in White John ,Abbott ,Head of State ,Prime Minister of Canada, 1891-93 James ,Abdnor ,Politician ,US Senator from South Dakota, 1981-87 John ,Abizaid ,Military ,C-in-C, US Central Command, 2003-