Rumicastrum Ulbrich (Montiaceae): a Beautiful Name for the Australian Calandrinias

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vegetation Type 14 - Rises of Loose Sand with Hard Spinifex

Vegetation Type 14 - Rises of loose sand with Hard Spinifex KEY # - Occurrence in vegetation type requires confirmation For more information visit N - Not charateristic in that vegetation community wildlife.lowecol.com.au F - Few plants occur /resources/vegetation-maps/ S - Some plants will occur M - Most likely to occur in the vegetation community Data courtesty of Albrecht, D., Pitts, B. (2004). The Vegetation and Plant Species of the Alice Springs Municipality Northern Territory. Department of Infrastructure, Planning and Environment & Greening Australia NT, Report 0724548580, Alice Springs, NT. Taxon Name Comments FreqCode Form Comments Abutilon otocarpum Keeled Lantern-bush, Desert Chinese Lantern, Desert Lantern S Herb Acacia aneura s.lat. Mulga, Broad-leaved Mulga M Tree Acacia brachystachya Umbrella Mulga, Umbrella Wattle, Turpentine Mulga S Shrub Acacia estrophiolata Ironwood, Southern Ironwood M Tree Acacia kempeana Witchetty Bush M Shrub Acacia murrayana Colony Wattle, Murrays Wattle M Shrub Acacia tetragonophylla Dead Finish, Kurara S Shrub Amyema hilliana Ironwood Mistletoe S Mistletoe Amyema maidenii subsp. maidenii Pale-leaf Mistletoe S Mistletoe Amyema preissii Wire-leaf Mistletoe S Mistletoe Aristida holathera var. holathera Erect Kerosene Grass, White Grass, Arrow Grass M Grass Blennodia canescens Wild Stock, Native Stock S Herb Boerhavia coccinea Tar Vine M # Herb Boerhavia repleta S Herb Boerhavia schomburgkiana Yipa M # Herb Brachyscome ciliaris complex Variable Daisy S Herb Calandrinia balonensis Broad-leaf Parakeelya S Herb Calandrinia reticulata S Herb Calotis erinacea Tangled Burr-daisy S Herb Capparis mitchellii Wild Orange, Native Orange, Bumble, Native Pomegranate N Tree Chenopodium desertorum subsp. anidiophyllum Desert Goosefoot, Frosted Goosefoot S Herb Chrysocephalum apiculatum Small Yellow Button, Common Everlasting, Yellow Buttons M Herb Convolvulus clementii Australian Bindweed, Pink Bindweed, Blushing Bindweed S Herb Corymbia opaca Bloodwood, Desert Bloodwood S Tree Crotalaria novae-hollandiae subsp. -

FINAL REPORT 2019 Canna Reserve

FINAL REPORT 2019 Canna Reserve This project was supported by NACC NRM and the Shire of Morawa through funding from the Australian Government’s National Landcare Program Canna Reserve BioBlitz 2019 Weaving and wonder in the wilderness! The weather may have been hot and dry, but that didn’t stop everyone having fun and learning about the rich biodiversity and conservation value of the wonderful Canna Reserve during the highly successful 2019 BioBlitz. On the 14 - 15 September 2019, NACC NRM together with support from Department of Biodiversity Conservation and Attractions and the Shire of Morawa, hosted their third BioBlitz at the Canna Reserve in the Shire of Morawa. Fifty professional biologists and citizen scientists attended the event with people travelling from near and far including Morawa, Perenjori, Geraldton and Perth. After an introduction and Acknowledgement of Country from organisers Jessica Stingemore and Jarna Kendle, the BioBlitz kicked off with participants separating into four teams and heading out to explore Canna Reserve with the goal of identifying as many plants, birds, invertebrates, and vertebrates as possible in a 24 hr period. David Knowles of Spineless Wonders led the invertebrate survey with assistance from, OAM recipient Allen Sundholm, Jenny Borger of Jenny Borger Botanical Consultancy led the plant team, BirdLife Midwest member Alice Bishop guided the bird survey team and David Pongracz from Department of Biodiversity Conservation and Attractions ran the vertebrate surveys with assistance from volunteer Corin Desmond. The BioBlitz got off to a great start identifying 80 plant species during the first survey with many more species to come and even a new orchid find for the reserve. -

August 2021 Issue No

Print ISSN 2208-4363 July – August 2021 Issue No. 612 Online ISSN 2208-4371 Office bearers President: David Stickney Secretary: Rose Mildenhall Treasurer: Marja Bouman Publicity Officer: Alix Williams Magazine editor: Tamara Leitch Conservation Coordinator: Denis Nagle Archivist: Marja Bouman Webmaster: John Sunderland Contact The Secretary Latrobe Valley Field Naturalists Club Inc. P.O. Box 1205 Golden-tip Goodia lotifolia photographed by Phil Rayment during the Club’s excursion to Morwell VIC 3840 Horseshoe Bend in September 2020. [email protected] 0428 422 461 Upcoming events Website Bird Group: Tuesday 3 August – Heyfield Wetlands. Meet 9am at the wetlands information centre. www.lvfieldnats.org Bird Group: Thursday 19 August – EA Wetlands survey. Meet 9am onsite. General meetings Botany Group: Saturday 31 July – Liverworts and mosses under the microscope at Baiba’s house. Held at 7:30 pm on the August general excursion: Saturday 28 August – Giffard with Mitch Smith. fourth Friday of each month Botany Group: Saturday 4 September – Holey Plains annual plant survey at the Newborough Uniting Bird Group: Tuesday 7 September – Sale Wetlands. Meet 9am at the carpark Church, Old Sale Road near the roundabout. Newborough VIC 3825 September general excursion: Saturday 25 September – Cranbourne Botanic Gardens Botany Group: Saturday 2 October – Mt Cannibal looking at recovery of plants after 2019 bushfires Club spring camp: 8-12 October at Brisbane Ranges Latrobe Valley Naturalist Issue no. 612 1 Tyers Park excursion 25.07.2020 It was good to have Club activities returning to a limited extent with an excursion in the south- western corner of Tyers Park on Saturday 25 July. -

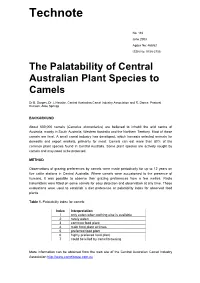

Palatability of Plants to Camels (DBIRD NT)

Technote No. 116 June 2003 Agdex No: 468/62 ISSN No: 0158-2755 The Palatability of Central Australian Plant Species to Camels Dr B. Dorges, Dr J. Heucke, Central Australian Camel Industry Association and R. Dance, Pastoral Division, Alice Springs BACKGROUND About 600,000 camels (Camelus dromedarius) are believed to inhabit the arid centre of Australia, mainly in South Australia, Western Australia and the Northern Territory. Most of these camels are feral. A small camel industry has developed, which harvests selected animals for domestic and export markets, primarily for meat. Camels can eat more than 80% of the common plant species found in Central Australia. Some plant species are actively sought by camels and may need to be protected. METHOD Observations of grazing preferences by camels were made periodically for up to 12 years on five cattle stations in Central Australia. Where camels were accustomed to the presence of humans, it was possible to observe their grazing preferences from a few metres. Radio transmitters were fitted on some camels for easy detection and observation at any time. These evaluations were used to establish a diet preference or palatability index for observed food plants. Table 1. Palatability index for camels Index Interpretation 1 only eaten when nothing else is available 2 rarely eaten 3 common food plant 4 main food plant at times 5 preferred food plant 6 highly preferred food plant 7 could be killed by camel browsing More information can be obtained from the web site of the Central Australian Camel Industry Association http://www.camelsaust.com.au 2 RESULTS Table 2. -

Management Plan Kaiserstuhl Conservation Park 2006

Department for Environment and Heritage Management Plan Kaiserstuhl Conservation Park 2006 www.environment.sa.gov.au This plan of management was adopted on 11 January 2006 and was prepared in pursuance of section 38 of the National Parks and Wildlife Act 1972. Government of South Australia Published by the Department for Environment and Heritage, Adelaide, Australia © Department for Environment and Heritage, 2006 ISBN: 1 921018 887 Front cover photograph courtesy of Bernd Stoecker FRPS and reproduced with his permission This document may be cited as “Department for Environment and Heritage (2006) Kaiserstuhl Conservation Park Management Plan, Adelaide, South Australia” FOREWORD Kaiserstuhl Conservation Park is located approximately 80 kilometres north-east of Adelaide and approximately 12 kilometres south-east of Tanunda, in the northern Mount Lofty Ranges. The 392 hectare park was proclaimed in 1979 to conserve a remnant block of native vegetation, in particular the northern-most population of Brown Stringybark (Eucalyptus baxteri). Kaiserstuhl Conservation Park preserves a substantial number of habitats for native fauna and helps to protect the soil and watershed of Tanunda Creek. More than 360 species of native plant are found within the reserve, many of which are of conservation significance. Bird species of conservation significance recorded within the reserve include the Diamond Firetail, White-browed Treecreeper, Elegant Parrot and Crescent Honeyeater. Kaiserstuhl Conservation Park also has a rich cultural heritage. The reserve is of significance to the Peramangk people and Ngadjuri people who have traditional associations with the land. Kaiserstuhl Conservation Park has also been a valuable source of material for botanical research. Dr Ferdinand von Mueller and Dr Hans Herman Behr collected Barossa Ranges plants from the area between 1844 and 1851. -

Bunjil Rocks Bioblitz Results

FINAL REPORT This project was supported by Northern Agricultural Catchments Council, Yarra Yarra Catchment Management Group and Moore Catchment Council, through funding from the Australian Government’s National Landcare Programme and Gunduwa Regional Conservation Association Bunjil Rocks BioBlitz A weekend of flora, fauna and fun! The weather may have been wet and windy, but that didn’t stop everyone having fun and learning more about the rich biodiversity and conservation value of Bunjil Rocks during the highly successful BioBlitz weekend. During 23 - 24 September 2017, the Northern Agricultural Catchments Council (NACC) together with partners Yarra Yarra Catchment Management Group (YYCMG) and Moore Catchment Council (MCC), hosted the inaugural Midwest BioBlitz at Bunjil Rocks More than 50 professional biologists and capable amateurs attended the event with people travelling from Geraldton, Northampton, Perth, Northam and Dowerin. After an introduction from organisers Jessica Stingemore, Lizzie King and Rachel Walmsley, the BioBlitz was kicked off by local Badimaya man Ashley Bell who, accompanied by his nephew Angus on didgeridoo, performed a fitting Welcome to Country – encouraging everyone to explore the local area, while also caring for the Country that has provided us with so much. MCC’s Community Landcare Coordinator Rachel Walmsley said participants were then split into groups with an ‘eco-guru’ team leader and spent the afternoon exploring and surveying the bush. “Gurus on-hand were Midwest flora expert Jenny Borger, bird enthusiast Phil Lewis, local landcare lover Paulina Wittwer, bat crazy and nest cam specialist Joe Tonga and all-round eco guru and fauna trapping expert Nic Dunlop,” she said. Team leaders exploring flora on the granite outcrops only had to walk about 50 metres before being able to identify over 120 species of plants, indicating the incredible diversity found on granite outcrops. -

Tanami Gas Pipeline Annual Rehabilitation Monitoring Preliminary Report 2021

Tanami Gas Pipeline Annual Rehabilitation Monitoring Preliminary Report 2021 Australian Gas Infrastructure Group © ECO LOGICAL AUSTRALIA PTY LTD 1 Tanami Gas Pipeline Annual Rehabilitation Monitoring Preliminary Report 2021 | Australian Gas Infrastructure Group DOCUMENT TRACKING Project Name Tanami Gas Pipeline Rehabilitation Monitoring Preliminary Report 2021 Project Number 18066 Project Manager Jeni Morris Prepared by Jeni Morris Reviewed by Jeff Cargill Approved by Jeff Cargill Status Draft Version Number v1 Last saved on 13 August 2021 This report should be cited as ‘Eco Logical Australia 2021. Tanami Gas Pipeline Rehabilitation Monitoring Preliminary Report 2021. Prepared for Australian Gas Infrastructure Group.’ ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This document has been prepared by Eco Logical Australia Pty Ltd with support from Australian Gas Infrastructure Group. Disclaimer This document may only be used for the purpose for which it was commissioned and in accordance with the contract between Eco Logical Australia Pty Ltd and Australian Gas Infrastructure Group. The scope of services was defined in consultation with Australian Gas Infrastructure Group, by time and budgetary constraints imposed by the client, and the availability of reports and other data on the subject area. Changes to available information, legislation and schedules are made on an ongoing basis and readers should obtain up to date information. Eco Logical Australia Pty Ltd accepts no liability or responsibility whatsoever for or in respect of any use of or reliance upon this report and its supporting material by any third party. Information provided is not intended to be a substitute for site specific assessment or legal advice in relation to any matter. Unauthorised use of this report in any form is prohibited. -

Hunter Valley Weeping Myall Woodland – Is It Really Definable and Defendable with and Without Weeping Myall (Acacia Pendula)?

Cunninghamia Date of Publication: June 2016 A journal of plant ecology for eastern Australia ISSN 0727- 9620 (print) • ISSN 2200 - 405X (Online) Hunter Valley Weeping Myall Woodland – is it really definable and defendable with and without Weeping Myall (Acacia pendula)? Stephen Bell and Colin Driscoll School of Environmental and Life Sciences, University of Newcastle, Callaghan NSW 2308 AUSTRALIA, [email protected], [email protected] Abstract: Hunter Valley Weeping Myall Woodland is listed as a Critically Endangered Ecological Community (CEEC) under both the New South Wales Threatened Species Conservation (TSC) Act 1995 and the Commonwealth Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation (EPBC) Act 1999. Uncertainty regarding the provenance of Weeping Myall (Acacia pendula) in the Hunter has led to questioning of the place of Hunter Valley Weeping Myall Woodland CEEC in State and Commonwealth legislation. A recent publication has endorsed its legislative listing, largely based on the co-association of Weeping Myall with a range of other semi-arid species in some parts of the Hunter Valley. We counter this argument and show that the semi-arid species present in low rainfall areas on Permian sediments of the Hunter Valley floor are in fact more widespread than previously documented. Through examination of distributional records, we demonstrate that these species display no fidelity to purported Hunter Valley Weeping Myall Woodland, but instead occur in a range of other vegetation communities across much of the central and upper Hunter Valley. Habitat suitability modelling undertaken for Acacia pendula shows there to be nearly 900 times the 200 ha of pre-European extent, or 20 times the area of occupancy previously estimated for this community. -

On the Flora of Australia

L'IBRARY'OF THE GRAY HERBARIUM HARVARD UNIVERSITY. BOUGHT. THE FLORA OF AUSTRALIA, ITS ORIGIN, AFFINITIES, AND DISTRIBUTION; BEING AN TO THE FLORA OF TASMANIA. BY JOSEPH DALTON HOOKER, M.D., F.R.S., L.S., & G.S.; LATE BOTANIST TO THE ANTARCTIC EXPEDITION. LONDON : LOVELL REEVE, HENRIETTA STREET, COVENT GARDEN. r^/f'ORElGN&ENGLISH' <^ . 1859. i^\BOOKSELLERS^.- PR 2G 1.912 Gray Herbarium Harvard University ON THE FLORA OF AUSTRALIA ITS ORIGIN, AFFINITIES, AND DISTRIBUTION. I I / ON THE FLORA OF AUSTRALIA, ITS ORIGIN, AFFINITIES, AND DISTRIBUTION; BEIKG AN TO THE FLORA OF TASMANIA. BY JOSEPH DALTON HOOKER, M.D., F.R.S., L.S., & G.S.; LATE BOTANIST TO THE ANTARCTIC EXPEDITION. Reprinted from the JJotany of the Antarctic Expedition, Part III., Flora of Tasmania, Vol. I. LONDON : LOVELL REEVE, HENRIETTA STREET, COVENT GARDEN. 1859. PRINTED BY JOHN EDWARD TAYLOR, LITTLE QUEEN STREET, LINCOLN'S INN FIELDS. CONTENTS OF THE INTRODUCTORY ESSAY. § i. Preliminary Remarks. PAGE Sources of Information, published and unpublished, materials, collections, etc i Object of arranging them to discuss the Origin, Peculiarities, and Distribution of the Vegetation of Australia, and to regard them in relation to the views of Darwin and others, on the Creation of Species .... iii^ § 2. On the General Phenomena of Variation in the Vegetable Kingdom. All plants more or less variable ; rate, extent, and nature of variability ; differences of amount and degree in different natural groups of plants v Parallelism of features of variability in different groups of individuals (varieties, species, genera, etc.), and in wild and cultivated plants vii Variation a centrifugal force ; the tendency in the progeny of varieties being to depart further from their original types, not to revert to them viii Effects of cross-impregnation and hybridization ultimately favourable to permanence of specific character x Darwin's Theory of Natural Selection ; — its effects on variable organisms under varying conditions is to give a temporary stability to races, species, genera, etc xi § 3. -

Species List

Biodiversity Summary for NRM Regions Species List What is the summary for and where does it come from? This list has been produced by the Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities (SEWPC) for the Natural Resource Management Spatial Information System. The list was produced using the AustralianAustralian Natural Natural Heritage Heritage Assessment Assessment Tool Tool (ANHAT), which analyses data from a range of plant and animal surveys and collections from across Australia to automatically generate a report for each NRM region. Data sources (Appendix 2) include national and state herbaria, museums, state governments, CSIRO, Birds Australia and a range of surveys conducted by or for DEWHA. For each family of plant and animal covered by ANHAT (Appendix 1), this document gives the number of species in the country and how many of them are found in the region. It also identifies species listed as Vulnerable, Critically Endangered, Endangered or Conservation Dependent under the EPBC Act. A biodiversity summary for this region is also available. For more information please see: www.environment.gov.au/heritage/anhat/index.html Limitations • ANHAT currently contains information on the distribution of over 30,000 Australian taxa. This includes all mammals, birds, reptiles, frogs and fish, 137 families of vascular plants (over 15,000 species) and a range of invertebrate groups. Groups notnot yet yet covered covered in inANHAT ANHAT are notnot included included in in the the list. list. • The data used come from authoritative sources, but they are not perfect. All species names have been confirmed as valid species names, but it is not possible to confirm all species locations. -

Encampment. Here Likewise Grew a Shrubby Species of Xerotes 110H

- 113 - encampment. Here likewise grew a shrubby species of Xerotes 110h hard rush-like leaves, but allied to X.gracilis.4 Mitchell sketched his quandong-like shrub, naming it Ellsalzarr1-.TsAyana. This plant was long known as Fusanusarsicarius, but in recent revisions, Mitchell t s name has been restored, so that the Quandong is now Eualya acuminata and the Bitter Quandong is E.murrayana. Mitchell thus became -the first explorer, apart from Cunningham, a professional botanist, to name and publish, albeit without the traditional Latin description, a native plant. Also on the Murray, he found a very beautiful, new, shrubby species of cassia, with thin papery pods and...the most brillant yellow blossoms...I would name it C.heteroloba.464 Lindley accepted this, and the plant was so named, although it proved to be synonymous with Cassia eremophila which had precedence. Similarly, Mitchell named Pelargonium rodne anum, which would be an acquisition to our gardens. I named it...in honour of Mrs. Riddell Sydney, grand-daughter of the famous Rodney.4-} On this expedition, Mitchell made his usual prophecies concerning the economy of the new country. He felt that the "quandong nut" and "gum 466 acacia may in time, become articles of commerce" and "having brought home specimens of most of the woods of the interior", Mitchell felt that several of the acacias would be valuable for ornamental work, having a pleasing perfume resembling that of a rose. Some are of a dark colour of various shades, and very compact; others light coloured and resembling in texture, box or lancewood...Specimens of these A pods may be seen at Hallets, No. -

Rangelands, Western Australia

Biodiversity Summary for NRM Regions Species List What is the summary for and where does it come from? This list has been produced by the Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities (SEWPC) for the Natural Resource Management Spatial Information System. The list was produced using the AustralianAustralian Natural Natural Heritage Heritage Assessment Assessment Tool Tool (ANHAT), which analyses data from a range of plant and animal surveys and collections from across Australia to automatically generate a report for each NRM region. Data sources (Appendix 2) include national and state herbaria, museums, state governments, CSIRO, Birds Australia and a range of surveys conducted by or for DEWHA. For each family of plant and animal covered by ANHAT (Appendix 1), this document gives the number of species in the country and how many of them are found in the region. It also identifies species listed as Vulnerable, Critically Endangered, Endangered or Conservation Dependent under the EPBC Act. A biodiversity summary for this region is also available. For more information please see: www.environment.gov.au/heritage/anhat/index.html Limitations • ANHAT currently contains information on the distribution of over 30,000 Australian taxa. This includes all mammals, birds, reptiles, frogs and fish, 137 families of vascular plants (over 15,000 species) and a range of invertebrate groups. Groups notnot yet yet covered covered in inANHAT ANHAT are notnot included included in in the the list. list. • The data used come from authoritative sources, but they are not perfect. All species names have been confirmed as valid species names, but it is not possible to confirm all species locations.