The Enemy Within: Religious Extremism, Political Violence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Doc Title Is Here

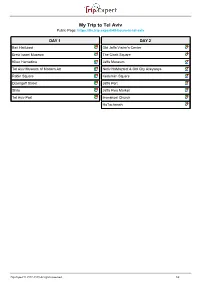

My Trip to Tel Aviv Public Page: https://tlv.trip.expert/48-hours-in-tel-aviv DAY 1 DAY 2 Beit Hatfutsot Old Jaffa Visitor's Center Eretz Israel Museum The Clock Square Kikar Hamedina Jaffa Museum Tel Aviv Museum of Modern Art Netiv HaMazalot & Old City Alleyways Rabin Square Kedumim Square Dizengoff Street Jaffa Port Shila Jaffa Flea Market Tel Aviv Port Immanuel Church HaTachanah Trip.Expert © 2017-2020 All rights reserved. 1/8 DAY 1 Beit Hatfutsot Address 15 Klausner Street, Tel Aviv University, Tel Aviv- Beit Hatfutsot - The Museum of the Jewish People, Yafo, Israel. is a museum like no other. The place is dedicated Phone Phone: + 972 (0)3 7457800 to the history of the Jewish people around the globe and is aiming to deepen the affinity of Jews Opening hours Sunday – Wednesday: 10:00 – 17:00 with their roots and identity. Situated in Tel Aviv Thursday: 10:00 – 22:00 University, Beit Hatfutsot (The Diaspora House) Friday: 9:00 – 14:00 Saturday: 10:00 – 15:00 captures the Jewish heritage in a touching and Closed: holiday's eves. moving way. They tell the turbulent history of the Hours might change from time to time, we advise Jewish people but provided you with hope. Their checking opening hours at the website before mission is educational, yet they keep you arrival. entertained. They exhibit an ancient story but do it in a gripping modern way. To fulfill its mission, Beit Transportation Dan: 7, 13, 24, 25, 45, 279, 289, 418 Egged: 126, 171, 274 Hatfutsot hosts several enthralling permanent Kavim: 36 exhibitions, few more temporary exhibitions and also unique and large databases of Jewish history Duration 2 - 3 hours and genealogy. -

Tourism in Tel Aviv Vision and Master Plan

2030TOURISM IN TEL AVIV VISION AND MASTER PLAN Mayor: Ron Huldai Mina Ganem –Senior Division Head for Strategic Planning and Director General: Menahem Leiba Policy, Ministry of Tourism Deputy Director General and Head of Operations: Rubi Zluf Alon Sapan – Director, Natural History Museum Deputy Director General of Planning, Organization and Shai Deutsch – Marketing Director, Arcadia Information Systems: Eran Avrahami Daphne Schiller – Tel Aviv University Deputy Director General of Human Resources: Avi Peretz Shana Krakowski – Director, Microfy Eviatar Gover – Tourism Entrepreneur Tourism in Tel Aviv 2030 is the Master Plan for tourism in Uri Douek – Traveltech Entrepreneur the city, which is derived from the City Vision released by the Lilach Zioni – Hotel Management Student Municipality in 2017. The Master Plan was formulated by Tel Yossi Falach –Lifeguard Station Manager, Tel Aviv Aviv Global & Tourism and the Strategic Planning Unit at the Leon Avigad – Owner, Brown Hotels Company Tel Aviv Municipality. Gannit Mayslits-Kassif – Architect and City Planner The Plan was written by two consulting firms, Matrix Dr. Avi Sasson – Professor of Israel Studies, Ashkelon College and AZIC, and facilitated by an advisory committee of Shiri Meir – Booking.com Representative professionals from the tourism industry. We wish to take this Yoram Blumenkranz – Artist opportunity to thank all our partners. Imri Galai – Airbnb Representative Tali Ginot –The David Intercontinental Hotel, Tel Aviv Tel Aviv Global & Tourism - Eytan Schwartz - CEO, Lior Meyer, -

Points of Interest

Points of Interest Azrieli Center (E3) Beaches (E1) Charles Clore Park (F1) Dizengoff Center (E2) Expo Tel Aviv (B4) Florentine (G2) HaBima Square & HaBima Theatre (E3) HaCarmel Market (F2) Nahalat Binyamin St. (F2) HaTachana Old Train Station (G2) HaYarkon Park (B4) Museum of the Jewish People (Beit HaTfutsot) (A3) MUZA (Eretz Israel Museum) (B3) Neve Tsedek (G2) Old Jaffa, The Flea Market (H1) Rabin Square, Yitshak Rabin Memorial (E2) Rothschild Blvd., Allenby St. (F2) Sarona Templar Colony (E3) Savidor Center Terminal (D4) Suzzane Dellal Center (G2) Tel Aviv Museum of Art & Performing Arts Center (E3) Tel Aviv Port (C2) Legend Bus Tourist Terminal Information Train Market Station Designated Hospital Beach 'Sherut' Taxi Route. Sherut taxis operate 7 days a week (Service hours are subject to change) Distance scale -

LEADERSHIP UNDER PRESSURE Yitzhak Rabin: the Price of Peace.1922-1995

LEADERSHIP UNDER PRESSURE Yitzhak Rabin: The Price of Peace.1922-1995. Park Avenue Synagogue. Monday May 18, 2020 Yoram Peri, "The Media and Collective Memory of Yitzhak Rabin's Remembrance", Journal of Communication, 2006. 1) Rabin’s assassination was a divisive event. This made it impossible to reach a consensus over the commemorative process. In the divided Israeli body politic, o2) Facing the groups that wished to commemorate the “victim of peace,” stood communities acting to blur the memory. 3) The contrast between Tel Aviv and Jerusalem. Tel Aviv, the city on the seashore with a cosmopolitan outlook, is the center of art and entertainment, and the city that represents the secular, democratic Israel. It is the stronghold of the peace camp. ..This city commemorated Rabin by changing the name of the square from Kings of Israel Square to Rabin Square and erecting a monument on the spot where he was killed. 4) Jerusalem, on the other hand, heavy with the weight of thousands of years of Jewish history, is the sacred symbolic focus of Jewish memory. It is the stronghold of the nationalist-clerical camp and it was in Jerusalem that the violent mass demonstrations against the Rabin government and the peace accords were held- very few commemorative events took place (except for those dictated by the location of the institution involved, such as the cemetery on Mt. Herzl or the Knesset building). Itamar Rabinovich, Yitzhak Rabin: Soldier, Leader, Statesman, 2017 1) Rabin’s assassination highlighted a stark contrast between “us” and “them.” Amir killed a man whose life and career represented the essence of Israel’s original establishment: East European origins, the Labor movement, Palmach (the elite military unit of prestate Israel) and Israel Defense Forces (IDF), a secular northern Tel Aviv. -

Demo Itinerary

Demo Itinerary https://tlv.trip.expert/demo Day 1 Overview Day 2 Overview Day 3 Overview Day 4 Overview Day 5 Overview Tel Aviv Port The Clock Square Bialik Street Haganah Museum The Israel Children's Museum Gan HaAtzmaut Jaffa Flea Market Kerem HaTeimanim Rothschild Boulevard Peres Park Frishman Beach Abu Hassan Carmel Market HaBima Theatre Beit Hatfutsot Charles Clore Park Jaffa Port Nachlat Binyamin Rabin Square Pedestrian Mall Tel Aviv University Etzel Museum Kedumim Square Tel Aviv Museum of Botanical Garden Shalom Meir Tower Modern Art HaTachanah Netiv HaMazalot & Old City Yarkon Park Alleyways Florentin Azrieli Center Neve Tzedek TLV Balloon HaPisga Garden Immanuel Church Sarona Complex Norma Jean Luna Park Al-Bahr Mosque Teder.FM Messa Port Tel Aviv brings you a Meymadion Mahmoudiya Mosque stunning view of the HaBima Square contains Habima Mediterranean Sea. It also Theater and Heichal HaTarbut The Children's Museum is one in included a farmer market with Kedumin Square is one of Jaffa (Culture Palace). The place has a a kind experience for all, with outstanding restaurants and food. highlights and has some of the magnificent design and exhibitions like no other. To make The market opens on weekdays best attractions in the city, architecture and nearby you can sure you will receive the from 9:00 to 20:00 except including: also find Helena Rubinstein experience fully it is a must to Sundays (at 14:00). On Friday - St. Peter's Church Pavilion, a lovely museum with book in advance. - Zodiac Signs Fountain free entrance. and Saturday the market closed Peres Park is an all family park, around 17:00 or 18:00. -

History and Memory in Tel Aviv and Jaffa Martin Wein Fall 2020

One Hundred Years: History and memory in Tel Aviv and Jaffa Martin Wein Fall 2020 Email: [email protected] Contact Info: Please use email, or office hours Tuesdays 3-4pm, thank you Course Credits: 3 TAU Semester Credits Time/Day: Tuesdays 4:15-7:30 pm (note variations of schedule on tour dates) Course Description (Summary) This course addresses issues of history and memory in Tel Aviv from its inception as a ‘green’ garden city, to the ‘white’ Bauhaus boom and the discourse about South Tel Aviv and Jaffa as a ‘black city.’ The course’s aim is to open up narratives about societies and public spaces, where a relationship between history and memory has been marked by political conflict, collective trauma, urban issues, and questions about the future. We will familiarize ourselves with multidisciplinary methodology that will enrich our understanding of Tel Aviv–Jaffa, the Holy Land, and the Middle East. As part of the course we will walk through the city from North to South, discussing history, memory, architecture, languages, city planning, and municipal politics on the way. Topics of discussion in the classroom and on the way will include prehistory and ancient history, Palestinian Arabs and Zionist Jews, ports and maritime history, industrialization and urban planning, politics and government, business and crime, education and cultural venues, old British influences, Asian migrant workers, African refugees, sports and parks, transportation and infrastructure, memorials and archaeological sites, language use in public space, and the city’s representation in Israeli film and literature. You will be required to participate in a walking lecture of three and a half hours, in small groups, “hands-on” and on–site. -

Hillel Schenker at Rabin Square, 12 Years On

Hillel Schenker at Rabin Square, 12 years on On Saturday evening, as I have done every year since that fatal night 12 years ago, I went to Rabin Square in the heart of Tel Aviv, opposite the municipality, to mark the anniversary of the assassination of Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin. It feels like a tribal ritual, but it is an act I am compelled to carry out each year, whatever the weather or my own state of mind or wellbeing. I was there on the night of November 4, 1995, 12 years ago. At the time there was a feeling that we were taking the streets back from the extremists on the right. The former Tel Aviv mayor Shlomo Lahat was the head of the organising committee, and the French Jewish philanthropist Jean Friedman also played a major part. As a member of the national leadership forum of the Peace Now movement, our role was to help bring out the demonstrators. There had been concern that not enough people would come, and that perhaps there would be hostile snipers stationed on the rooftops around the square – but the people came, over 100,000, to take back the night from the rejectionist forces of darkness. I remember being particularly upbeat after Rabin spoke. He was not a great speaker, and tended frequently to place the wrong emphases within his sentences, perhaps due to the fact that he had never totally gotten used to the necessities of public life. This time, I remarked to those around me, he spoke well, perhaps gaining strength from the masses below him. -

What's on in Tel Aviv /December

WHAT'S ON IN TEL AVIV / DECEMBER MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY SUNDAY 1 2 3 4 SARONA MARKET ROBERT GLASPER BEATING HEART, CONCERT FOREVER YOUNG - FOOD TOUR EXPERIMENT NO.2 BOB DYLAN AT 75 Get to know the most JAZZ CONCERT MUSIC CONCERT EXHIBITION promising chefs of Tel Aviv 10 PM 8:30 PM Ongoing until APR 2017 and discover more than 80 Tel Aviv Performing Arts Tel Aviv Museum of Art Museum of the Jewish People food stands and stores. Every Center (Beit Hatfutsot) Monday and Thursday ISRAELI FOLK DANCING Book: visit-tel-aviv.com/tours Every Saturday 11 AM Gordon Beach Promenade NORMA > OPERA, DEC 1-15, Tel Aviv Performing Arts Center 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 THE BAUHAUS LORD OF THE FKJ BILLY ELLIOT PICH - MARTIN HARRIAGUE ORLY PORTAL - SWIRIA ISRAEL BUSINESS #ITSALLDESIGN DANCE ELECTRONIC MUSIC CONCERT MUSICAL CONTEMPOARY DANCE CONTEMPORARY DANCE CONFERENCE EXHIBITION IRISH MUSIC 8:30 PM Barby Club DEC 8-28 2 PM Suzanne Dellal Center 9:30 PM DEC 11-12 David Intercontinental Hotel Until JAN 7 AND DANCE MICROSOFT TECH SUMMIT Cinema City, Ramat Hasharon TOY DOLLS Suzanne Dellal Center Tel Aviv Museum of Art SHOW DEC 7-8 BUENOS AIRES NIGHTS PUNK CONCERT PUCCINI HEROINES DEC 6-8 Tel Aviv Convention Center Bronfman SPECTACULAR LATINO 9:30 PM Reading 3 SATURDAY MORNING Auditorium INTL. DANCE EXPOSURE RHYTHM AND COLOR SHOW OPERA DEC 7-11 Suzanne Dellal Center 8 PM 11:00 AM Auditorium, Bat Yam Tel Aviv Performing Arts Center JAZZ FESTIVAL > DEC 7-9, Tel Aviv Cinematheque NORMA > OPERA, DEC 1-15, Tel Aviv Performing Arts Center 12 13 14 -

Tel Aviv University International Time TBD (Note Variations of Schedule on Tour Dates) Instructor: Martin J

Tel Aviv University International Time TBD (note variations of schedule on tour dates) Instructor: Martin J. Wein, Ph.D. [email protected] One Hundred Years: History and Memory in Tel Aviv–Jaffa This course addresses issues of history and memory in Tel Aviv from its inception as a ‘green’ garden city, to the ‘white’ Bauhaus boom and the discourse about South Tel Aviv and Jaffa as a ‘black city.’ The course’s aim is to open up narratives about society and public space in Israel, where the relationship between history and memory has been marked by political conflict, collective trauma, urban issues, and uncertainty about the future. We will familiarize ourselves with multidisciplinary methodology that will enrich our understanding of Tel Aviv–Jaffa, Israel, the Holy Land, and the Middle East. As part of the course we will walk through the city from North to South, discussing history, architecture, language and municipal politics on the way. Topics of discussion in the classroom and on the way will include prehistory and ancient history, Palestinian Arabs and Zionist Jews, ports and maritime history, industrialization and urban planning, politics and government, business and crime, education and cultural venues, old British influences, Asian migrant workers, African refugees, sports and parks, transportation and infrastructure, memorials and archaeological sites, language use in public space, and the city’s representation in Israeli film and literature. You will be required to participate in a walking lecture of three and a half hours, in small groups, “hands-on” and on–site. It is important that you come well fed, bring comfortable shoes and clothes, a cap, an umbrella/sun glasses/sun lotion and water, as well as change for drinks and the bus. -

Of Tel Aviv-Jaffa

Topics in Humanities: The Making (and Remaking) of Tel Aviv-Jaffa Class code Instructor Details Dr. Martin J. Wein [email protected] Office hours by appointment Class Details Seminar Time to be confirmed. Prerequisites Procure a standard map of the city, printed by MAPA publishing house. Class The Holy Land is a tiny global microcosm, with a complexity beyond imagination. A remarkable concentration of rare natural features, mostly connected to the Great Rift Valley, combines with Description multiple layers of human settlements since prehistory which are forming tells, artificial hills dotting the landscapes of the Middle East. Jaffa, perhaps the last Levantine “port city” and Jerusalem's ancient sea port, rose rapidly after the opening of the Suez canal in 1869, and eventually became a Zionist melting pot, with Jewish communities from around the world, Palestinian Arabs, African refugees, and Asian migrant workers now adding to a multilingual, multiethnic mosaic of 3.5 million people. Israel's coastal metropolis commonly dubbed “Tel Aviv,” originally only the name of a suburb of Jaffa, has today several historical tells in the area of the municipality, the most significant one just underneath Jaffa's—mostly destroyed—Old City. But the coastal agglomeration has been largely built on often intensively-farmed agricultural land, engulfing Muslim and Christian villages, advancing a few miles in a radius around the Old City of Jaffa every decade of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. At the same time that the modernist “Bauhaus”-style architecture flourished, local orange production catered to maritime traffic, offering special types of citrus fruit with long shelf lives needed by seafarers as a vitamin C source against scurvy. -

Norman Hotel

BULLETIN ISSUE NO.2 REDEFINING LUXURY AT THE NORMAN THE NORMAN BULLETIN ISSUE 002 TABLE OF CONTENTS 01 07 13 the legacy of a vision the norman a new view on THE NORMAN STORY SUITES ISRAELI TERROIR p. 6-7 p. 20-21 p. 46-47 02 08 14 a dream in the making guest services modern RAISING THE BAR FAMILIES ISRAELI FOOD p. 8-9 & CHILDREN p. 48-49 p. 22 03 09 15 in conversation with discover the library bar CHEF BARAK AHARONI TEL AVIV PROLOGUE p. 12-13 p. 24-33 p. 50-51 04 10 16 curating take care a poem THE NORMAN WINE WELLNESS CASTLE IN THE SAND COLLECTION p. 34-35 p. 52-53 p. 14-15 05 11 in conversation with the legacy of the past CHEF MASAKI SUGISAKI DOLPHIN HOUSE p. 16 p. 36-37 06 12 the norman guest services CULINARY ARTS EXCURSIONS p. 18-19 & TOURS p. 40-43 01 THE NORMAN STORY THE LEGACY OF A VISION. A STORY OF COURAGE, CREATIVITY AND CHARM The Norman Tel Aviv was built in memory of Norman Lourie, an This groundbreaking work, which portrays the triumph of an early extraordinary man with a multi-faceted vision and far-reaching legacy kibbutz on the Dead Sea, is preserved in the Steven Spielberg Jewish that has reverberated across continents. From South African pioneer Film Archive in Jerusalem. and prizewinning filmmaker, to founder of Israel’s first luxury hotel resort, Dolphin House, Norman Lourie was a man who lived many In addition to promoting the newly-formed Jewish State through lifetimes. -

ELAL Guide to Tel Aviv Israel Frequent Flyer Club

9 Flight Status Australia EN Passenger Information TravelELAL guide to Tel Aviv Israel Frequent Flyer Club Login Accessibility Israel’s Culture and Sunshine Capital Thinking about traveling to Tel Aviv? Our comprehensive online guide will inform you of everything you need to know in order to plan a successful trip to Tel Aviv. It offers weather tips, recommendations on attractions, hotels, transportation, shopping, dining, child friendly activities, museums, and useful insider travel tips. The weather in Tel Aviv is almost always sunny. The summers are very hot and humid. The winters are mild, and although they can get rainy, the majority of the days are gorgeous and sunshine is plentiful. Get to Know Tel Aviv All year round Tel Aviv, the cultural heart of Israel, is pulsing with culture, fashion, nightlife, restaurants and cafes. The gorgeous beaches offer the perfect balance to the bustling urban nature of city life. This city is famous for its Bauhaus architecture, laid back cafes, thriving markets, boutiques, fine dining, world class nightclubs, street art and beautiful sunsets. A walk down the promenade will bring you to the ancient and multi- cultural city of Jaffa, which perfectly complements the modernity of Tel Aviv. The city offers amazing luxury hotels by the sea such as the Dan Hotel, and urban boutique hotels such as the Brown Hotel near Nachalat Binyamin. You will not be disappointed with the shopping either. Check out the country’s most sophisticated shopping areas in north Tel Aviv, latest fashion trends in Hachashmal, and artisan goods from Nachalat Binyamin’s street fairs.