Mauna Loa and Global Trends in Air Quality

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Changing Carbon Cycle at Mauna Loa Observatory

The changing carbon cycle at Mauna Loa Observatory Wolfgang Buermann*†, Benjamin R. Lintner‡§, Charles D. Koven*, Alon Angert*¶, Jorge E. Pinzonʈ, Compton J. Tuckerʈ, and Inez Y. Fung*,** *Berkeley Atmospheric Sciences Center and ‡Department of Geography, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720; and ʈNational Aeronautics and Space Administration/Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, MD 20771 Contributed by Inez Y. Fung, December 29, 2006 (sent for review July 6, 2006) The amplitude of the CO2 seasonal cycle at the Mauna Loa Obser- Several studies have analyzed variability in the MLO CO2 vatory (MLO) increased from the early 1970s to the early 1990s but seasonal cycle to infer the sensitivity of ecosystem dynamics to decreased thereafter despite continued warming over northern climate perturbations. The increasing trends in the seasonal continents. Because of its location relative to the large-scale amplitude of CO2 at the MLO and Point Barrow, AK, from the atmospheric circulation, the MLO receives mainly Eurasian air early 1970s to the early 1990s are postulated to be evidence of masses in the northern hemisphere (NH) winter but relatively more a temperature-related lengthening of the boreal growing season North American air masses in NH summer. Consistent with this (1). Reports of a greening trend in the satellite-derived normal- seasonal footprint, our findings indicate that the MLO amplitude ized difference vegetation index (NDVI) throughout the 1980s registers North American net carbon uptake during the warm at northern high latitudes consistent with springtime warming season and Eurasian net carbon release as well as anomalies in provided additional support for this hypothesis (5). -

Surface Ozone in the Southern Hemisphere: 20 Years of Data from a Site with a Unique Setting in El Tololo, Chile

Atmos. Chem. Phys., 17, 6477–6492, 2017 www.atmos-chem-phys.net/17/6477/2017/ doi:10.5194/acp-17-6477-2017 © Author(s) 2017. CC Attribution 3.0 License. Surface ozone in the Southern Hemisphere: 20 years of data from a site with a unique setting in El Tololo, Chile Julien G. Anet1,2, Martin Steinbacher1, Laura Gallardo3,4, Patricio A. Velásquez Álvarez5,6, Lukas Emmenegger1, and Brigitte Buchmann1 1Laboratory for Air Pollution/Environmental Technology, Swiss Federal Laboratories for Materials Science and Technology Empa, Duebendorf, Switzerland 2WSL Institute for Snow and Avalanche Research SLF, Davos, Switzerland 3Departamento de Geofísica de la Universidad de Chile, Blanco Encalada 2002, piso 4, Santiago, Chile 4Center for Climate and Resilience Research (CR2), Blanco Encalada 2002, Santiago, Chile 5Dirección Meteorológica de Chile, Av. Portales 3450, Estación Central, Santiago, Chile 6Climate and Environmental Physics, Physics Institute, University of Bern, Bern, Switzerland Correspondence to: Julien G. Anet ([email protected]) and Martin Steinbacher ([email protected]) Received: 12 July 2016 – Discussion started: 7 October 2016 Revised: 24 March 2017 – Accepted: 25 April 2017 – Published: 31 May 2017 Abstract. The knowledge of surface ozone mole fractions located over the Pacific Ocean. Therefore, due to the neg- and their global distribution is of utmost importance due to ligible influence of local processes, the ozone record also al- the impact of ozone on human health and ecosystems and the lows studying the influence of El Niño and La Niña episodes central role of ozone in controlling the oxidation capacity of on background ozone levels in South America. -

2018 NOAA Science Report National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration U.S

2018 NOAA Science Report National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration U.S. Department of Commerce NOAA Technical Memorandum NOAA Research Council-001 2018 NOAA Science Report Harry Cikanek, Ned Cyr, Ming Ji, Gary Matlock, Steve Thur NOAA Silver Spring, Maryland February 2019 NATIONAL OCEANIC AND NOAA Research Council noaa ATMOSPHERIC ADMINISTRATION 2018 NOAA Science Report Harry Cikanek, Ned Cyr, Ming Ji, Gary Matlock, Steve Thur NOAA Silver Spring, Maryland February 2019 UNITED STATES NATIONAL OCEANIC National Oceanic and DEPARTMENT OF AND ATMOSPHERIC Atmospheric Administration COMMERCE ADMINISTRATION Research Council Wilbur Ross RDML Tim Gallaudet, Ph.D., Craig N. McLean Secretary USN Ret., Acting NOAA NOAA Research Council Chair Administrator Francisco Werner, Ph.D. NOAA Research Council Vice Chair NOTICE This document was prepared as an account of work sponsored by an agency of the United States Government. The views and opinions of the authors expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the United States Government or any agency or Contractor thereof. Neither the United States Government, nor Contractor, nor any of their employees, make any warranty, express or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, product, or process disclosed, or represents that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. Mention of a commercial company or product does not constitute an endorsement by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. -

Mauna Loa Reconnaissance 2003

“Giant of the Pacific” Mauna Loa Reconnaissance 2003 Plan of encampment on Mauna Loa summit illustrated by C. Wilkes, Engraved by N. Gimbrede (Wilkes 1845; vol. IV:155) Prepared by Dennis Dougherty B.A., Project Director Edited by J. Moniz-Nakamura, Ph. D. Principal Investigator Pacific Island Cluster Publications in Anthropology #4 National Park Service Hawai‘i Volcanoes National Park Department of the Interior 2004 “Giant of the Pacific” Mauna Loa Reconnaissance 2003 Prepared by Dennis Dougherty, B.A. Edited by J. Moniz-Nakamura, Ph.D. National Park Service Hawai‘i Volcanoes National Park P.O. Box 52 Hawaii National Park, HI 96718 November, 2004 Mauna Loa Reconnaissance 2003 Executive Summary and Acknowledgements The Mauna Loa Reconnaissance project was designed to generate archival and inventory/survey level recordation for previously known and unknown cultural resources within the high elevation zones (montane, sub-alpine, and alpine) of Mauna Loa. Field survey efforts included collecting GPS data at sites, preparing detailed site plan maps and feature descriptions, providing site assessment and National Register eligibility, and integrating the collected data into existing site data bases within the CRM Division at Hawaii Volcanoes National Park (HAVO). Project implementation included both pedestrian transects and aerial transects to accomplish field survey components and included both NPS and Research Corporation University of Hawaii (RCUH) personnel. Reconnaissance of remote alpine areas was needed to increase existing data on historic and archeological sites on Mauna Loa to allow park managers to better plan for future projects. The reconnaissance report includes a project introduction; background sections including physical descriptions, cultural setting overview, and previous archeological studies; fieldwork sections describing methods, results, and feature and site summaries; and a section on conclusions and findings that provide site significance assessments and recommendations. -

Hawaiian Volcanoes: from Source to Surface Site Waikolao, Hawaii 20 - 24 August 2012

AGU Chapman Conference on Hawaiian Volcanoes: From Source to Surface Site Waikolao, Hawaii 20 - 24 August 2012 Conveners Michael Poland, USGS – Hawaiian Volcano Observatory, USA Paul Okubo, USGS – Hawaiian Volcano Observatory, USA Ken Hon, University of Hawai'i at Hilo, USA Program Committee Rebecca Carey, University of California, Berkeley, USA Simon Carn, Michigan Technological University, USA Valerie Cayol, Obs. de Physique du Globe de Clermont-Ferrand Helge Gonnermann, Rice University, USA Scott Rowland, SOEST, University of Hawai'i at M noa, USA Financial Support 2 AGU Chapman Conference on Hawaiian Volcanoes: From Source to Surface Site Meeting At A Glance Sunday, 19 August 2012 1600h – 1700h Welcome Reception 1700h – 1800h Introduction and Highlights of Kilauea’s Recent Eruption Activity Monday, 20 August 2012 0830h – 0900h Welcome and Logistics 0900h – 0945h Introduction – Hawaiian Volcano Observatory: Its First 100 Years of Advancing Volcanism 0945h – 1215h Magma Origin and Ascent I 1030h – 1045h Coffee Break 1215h – 1330h Lunch on Your Own 1330h – 1430h Magma Origin and Ascent II 1430h – 1445h Coffee Break 1445h – 1600h Magma Origin and Ascent Breakout Sessions I, II, III, IV, and V 1600h – 1645h Magma Origin and Ascent III 1645h – 1900h Poster Session Tuesday, 21 August 2012 0900h – 1215h Magma Storage and Island Evolution I 1215h – 1330h Lunch on Your Own 1330h – 1445h Magma Storage and Island Evolution II 1445h – 1600h Magma Storage and Island Evolution Breakout Sessions I, II, III, IV, and V 1600h – 1645h Magma Storage -

Keeling Curve: Result, Interpretation & Global Monitoring

International Journal for Empirical Education and Research Keeling Curve: Result, Interpretation & Global Monitoring Augustyn Ostrowski Faculty of Geography & Geology Jagiellonian University Email: [email protected] (Author of Correspondence) Poland Abstract The Keeling Curve is a graph of the accumulation of carbon dioxide in the Earth's atmosphere based on continuous measurements taken at the Mauna Loa Observatory on the island of Hawaii from 1958 to the present day. The curve is named for the scientist Charles David Keeling, who started the monitoring program and supervised it until his death in 2005. Keywords: Mauna Loa Measurements; Results and Interpretation; Global Monitoring; Ralph Keeling. ISSN Online: 2616-4833 ISSN Print: 2616-4817 35 1. Introduction Keeling's measurements showed the first significant evidence of rapidly increasing carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere. According to Dr Naomi Oreskes, Professor of History of Science at Harvard University, the Keeling curve is one of the most important scientific works of the 20th century. Many scientists credit the Keeling curve with first bringing the world's attention to the current increase of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. Prior to the 1950s, measurements of atmospheric carbon dioxide concentrations had been taken on an ad hoc basis at a variety of locations. In 1938, engineer and amateur meteorologist Guy Stewart Callendar compared datasets of atmospheric carbon dioxide from Kew in 1898-1901, which averaged 274 parts per million by volume (ppm), and from the eastern United States in 1936-1938, which averaged 310 ppmv, and concluded that carbon dioxide concentrations were rising due to anthropogenic emissions. However, Callendar's findings were not widely accepted by the scientific community due to the patchy nature of the measurements. -

NOAA Mauna Loa Facility Electrical and Grounding Survey February 26, 2021

NOAA Mauna Loa Facility Electrical and Grounding Survey February 26, 2021 Lee Santoro Electrical Engineer Summit Kinetics Andrew Cooper Electrical Engineer Summit Kinetics 1 Abstract At the request of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) a survey of the electrical and grounding systems of the Mauna Loa Observatory (MLO) was undertaken. MLO is a premier atmospheric research facility that has been continuously monitoring and collecting data related to atmospheric change since the 1950's. The electrical and grounding systems of the MLO facility have evolved over six decades of use, modified and expanded as the scientific needs of the facility have changed. The result is a patchwork of old and newer systems built to the prevailing standards of the era in which they were installed. The report outlines the geological and resultant extreme electrical isolation from reasonably conductive soil and ground water at this site. The site’s extremely poor ground conductivity provides no practical remediation using a conventional approach for a properly earthed grounding electrode system. As a result, the conclusions and recommendations provided treat the site as a whole, similar to a ship, requiring extraordinary efforts to provide a safe and effective grounding system. The high level results of this survey are contained in this report, along with recommendations for the improvement of these systems. The goal is to support the continued atmospheric and climate research that is proving ever more critical in this era of climate change. -

Volcanic and Seismic Hazards on the Island of Hawaii

U.S. Department of the Interior / U.S. Geological Survey Volcanic and Seismic Hazards on the Island of Hawaii Volcanic and Seismic Hazards on the Island of Hawaii Lava flows entered Kalapana Gardens in December 1986. Front Cover: View of Kapoho village during the 1960 eruption before it was entirely destroyed. (Photographer unknown) Inside Front Cover (Photograph by J.D. Griggs) For sale by the U.S. Government Printing Office Superintendent of Documents, Mail Stop: SSOP, Washington, DC 20402-9328 ISBN 0-16-038200-9 Preface he eruptions of volcanoes often have direct, dramatic effects on the lives of people and Ton their property. People who live on or near active volcanoes can benefit greatly from clear, scientific information about the volcanic and seismic hazards of the area. This booklet provides such information for the residents of Hawaii so they may effectively deal with the special geologic hazards of the island. Identifying and evaluating possible geologic hazards is one of the principal roles of the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) and its Hawaiian Volcano Observatory. When USGS scientists recognize a potential hazard, such as an impend ing eruption, they notify the appropriate govern ment officials, who in turn are responsible for advising the public to evacuate certain areas or to take other actions to insure their safety. This booklet was prepared in cooperation with the Hawaii County Civil Defense Agency. Volcanic and Seismic Hazards: Interagency Responsibilities Hawaii County National Park } Civil Defense C Service ./ Short-term hazard evaluation for the agencies responsible for public safety. Information on volcanic U.S. -

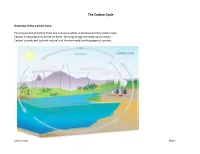

The Carbon Cycle

The Carbon Cycle Overview of the Carbon Cycle The movement of carbon from one area to another is the basis for the carbon cycle. Carbon is important for all life on Earth. All living things are made up of carbon. Carbon is produced by both natural and human-made (anthropogenic) sources. Carbon Cycle Page 1 Nature’s Carbon Sources Carbon is found in the Carbon is found in the lithosphere Carbon is found in the Carbon is found in the atmosphere mostly as carbon in the form of carbonate rocks. biosphere stored in plants and hydrosphere dissolved in ocean dioxide. Animal and plant Carbonate rocks came from trees. Plants use carbon dioxide water and lakes. respiration place carbon into ancient marine plankton that sunk from the atmosphere to make the atmosphere. When you to the bottom of the ocean the building blocks of food Carbon is used by many exhale, you are placing carbon hundreds of millions of years ago during photosynthesis. organisms to produce shells. dioxide into the atmosphere. that were then exposed to heat Marine plants use cabon for and pressure. photosynthesis. The organic matter that is produced Carbon is also found in fossil fuels, becomes food in the aquatic such as petroleum (crude oil), coal, ecosystem. and natural gas. Carbon is also found in soil from dead and decaying animals and animal waste. Carbon Cycle Page 2 Natural Carbon Releases into the Atmosphere Carbon is released into the atmosphere from both natural and man-made causes. Here are examples to how nature places carbon into the atmosphere. -

Hawaiʻi Board on Geographic Names Correction of Diacritical Marks in Hawaiian Names Project - Hawaiʻi Island

Hawaiʻi Board on Geographic Names Correction of Diacritical Marks in Hawaiian Names Project - Hawaiʻi Island Status Key: 1 = Not Hawaiian; 2 = Not Reviewed; 3 = More Research Needed; 4 = HBGN Corrected; 5 = Already Correct in GNIS; 6 = Name Change Status Feat ID Feature Name Feature Class Corrected Name Source Notes USGS Quad Name 1 365008 1940 Cone Summit Mauna Loa 1 365009 1949 Cone Summit Mauna Loa 3 358404 Aa Falls Falls PNH: not listed Kukuihaele 5 358406 ʻAʻahuwela Summit ‘A‘ahuwela PNH Puaakala 3 358412 Aale Stream Stream PNH: not listed Piihonua 4 358413 Aamakao Civil ‘A‘amakāō PNH HBGN: associative Hawi 4 358414 Aamakao Gulch Valley ‘A‘amakāō Gulch PNH Hawi 5 358415 ʻĀʻāmanu Civil ‘Ā‘āmanu PNH Kukaiau 5 358416 ʻĀʻāmanu Gulch Valley ‘Ā‘āmanu Gulch PNH HBGN: associative Kukaiau PNH: Ahalanui, not listed, Laepao‘o; Oneloa, 3 358430 Ahalanui Laepaoo Oneloa Civil Maui Kapoho 4 358433 Ahinahena Summit ‘Āhinahina PNH Puuanahulu 5 1905282 ʻĀhinahina Point Cape ‘Āhinahina Point PNH Honaunau 3 365044 Ahiu Valley PNH: not listed; HBGN: ‘Āhiu in HD Kau Desert 3 358434 Ahoa Stream Stream PNH: not listed Papaaloa 3 365063 Ahole Heiau Locale PNH: Āhole, Maui Pahala 3 1905283 Ahole Heiau Locale PNH: Āhole, Maui Milolii PNH: not listed; HBGN: Āholehōlua if it is the 3 1905284 ʻĀhole Holua Locale slide, Āholeholua if not the slide Milolii 3 358436 Āhole Stream Stream PNH: Āhole, Maui Papaaloa 4 358438 Ahu Noa Summit Ahumoa PNH Hawi 4 358442 Ahualoa Civil Āhualoa PNH Honokaa 4 358443 Ahualoa Gulch Valley Āhualoa Gulch PNH HBGN: associative Honokaa -

Climate Change: Evidence & Causes 2020

Climate Change Evidence & Causes Update 2020 An overview from the Royal Society and the US National Academy of Sciences n summary Foreword CLIMATE CHANGE IS ONE OF THE DEFINING ISSUES OF OUR TIME. It is now more certain than ever, based on many lines of evidence, that humans are changing Earth’s climate. The atmosphere and oceans have warmed, which has been accompanied by sea level rise, a strong decline in Arctic sea ice, and other climate-related changes. The impacts of climate change on people and nature are increasingly apparent. Unprecedented flooding, heat waves, and wildfires have cost billions in damages. Habitats are undergoing rapid shifts in response to changing temperatures and precipitation patterns. The Royal Society and the US National Academy of Sciences, with their similar missions to promote the use of science to benefit society and to inform critical policy debates, produced the original Climate Change: Evidence and Causes in 2014. It was written and reviewed by a UK-US team of leading climate scientists. This new edition, prepared by the same author team, has been updated with the most recent climate data and scientific analyses, all of which reinforce our understanding of human-caused climate change. The evidence is clear. However, due to the nature of science, not every detail is ever totally settled or certain. Nor has every pertinent question yet been answered. Scientific evidence continues to be gathered around the world. Some things have become clearer and new insights have emerged. For example, the period of slower warming during the 2000s and early 2010s has ended with a dramatic jump to warmer temperatures between 2014 and 2015. -

District 6 Boundaries

District: 6 Beginning at the intersection of trail and school district boundary and running (1) Southerly along said boundary to Volcano CDP boundary; (2) Easterly along said boundary to Olaa Rain Forest boundary; (3) Southeasterly along said boundary to Olaa Forest Reserve boundary; (4) Southeasterly along said boundary to Volcano Road; (5) Southwesterly along said road to Kahaualea Road; (6) Southeasterly along said road to Kahaualea Natural Area Reserve boundary; (7) Westerly along said boundary to Hawaii Volcanoes National Park boundary; (8) Southeasterly along said boundary to Hawaii shoreline; (9) Westerly along said shoreline to jeep trail extension; (10) Southeasterly along said extension to jeep trail; (11) Easterly along said jeep trail to Mamalahoa Bypass Road; (12) Southeasterly along said road to jeep trail; (13) Easterly along said jeep trail to unnamed road; (14) Easterly along said road(s) (TLID 614323848, 203002918) to Mamalahoa Highway; (15) Northerly along said highway to Honuaino Street; (16) Easterly along said street to Kealakekua CDP boundary; (17) Northerly along said boundary to rock wall; (18) Easterly along said wall to Kealakekua CDP boundary; (19) Easterly along said boundary to jeep trail; (20) Southeasterly along said jeep trail to North Kona - South Kona District boundary; (21) Easterly along said boundary to jeep trail; (22) Easterly along said jeep trail to North Kona - South Kona District boundary; (23) Southerly along said boundary to jeep trail; (24) Easterly along said jeep trail to Kau - North Kona District boundary; (25) Northeasterly along said boundary to Hawaii Volcanoes National Park boundary; (26) Northeasterly along said boundary to Mauna Loa Trail; (27) Northeasterly along said trail to Hamakua - North Hilo District boundary; (28) Northerly along said boundary to Mauna Loa Observatory Road; (29) Easterly along said road to trail; (30) Easterly along said trail to point of beginning.