A BLINDING FLASH of LIGHT David Tomas Is an Artist and Writer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“America” on Nineteenth-Century Stages; Or, Jonathan in England and Jonathan at Home

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by D-Scholarship@Pitt PLAYING “AMERICA” ON NINETEENTH-CENTURY STAGES; OR, JONATHAN IN ENGLAND AND JONATHAN AT HOME by Maura L. Jortner BA, Franciscan University, 1993 MA, Xavier University, 1998 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2005 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by It was defended on December 6, 2005 and approved by Heather Nathans, Ph.D., University of Maryland Kathleen George, Ph.D., Theatre Arts Attilio Favorini, Ph.D., Theatre Arts Dissertation Advisor: Bruce McConachie, Ph.D., Theatre Arts ii Copyright © by Maura L. Jortner 2005 iii PLAYING “AMERICA” ON NINETEENTH-CENTURY STAGES; OR, JONATHAN IN ENGLAND AND JONATHAN AT HOME Maura L. Jortner, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2005 This dissertation, prepared towards the completion of a Ph.D. in Theatre and Performance Studies at the University of Pittsburgh, examines “Yankee Theatre” in America and London through a post-colonial lens from 1787 to 1855. Actors under consideration include: Charles Mathews, James Hackett, George Hill, Danforth Marble and Joshua Silsbee. These actors were selected due to their status as iconic performers in “Yankee Theatre.” The Post-Revolutionary period in America was filled with questions of national identity. Much of American culture came directly from England. American citizens read English books, studied English texts in school, and watched English theatre. They were inundated with English culture and unsure of what their own civilization might look like. -

The Art of the Icon: a Theology of Beauty, Illustrated

THE ART OF THE ICON A Theology of Beauty by Paul Evdokimov translated by Fr. Steven Bigham Oakwood Publications Pasadena, California Table of Contents SECTION I: BEAUTY I. The Biblical Vision of Beauty II. The Theology of Beauty in the Fathers III. From Æsthetic to Religious Experience IV. The Word and the Image V. The Ambiguity of Beauty VI. Culture, Art, and Their Charisms VII. Modern Art in the Light of the Icon SECTION II: THE SACRED I. The Biblical and Patristic Cosmology II. The Sacred III. Sacred Time IV. Sacred Space V. The Church Building SECTION III: THE THEOLOGY OF THE ICON I. Historical Preliminaries II. The Passage from Signs to Symbols III. The Icon and the Liturgy IV. The Theology of Presence V. The Theology of the Glory-Light VI. The Biblical Foundation of the Icon VII. Iconoclasm VIII. The Dogmatic Foundation of the Icon IX. The Canons and Creative Liberty X. The Divine Art XI. Apophaticism SECTION IV: A THEOLOGY OF VISION I. Andrei Rublev’s Icon of the Holy Trinity II. The Icon of Our Lady of Vladimir III. The Icon of the Nativity of Christ IV. The Icon of the Lord’s Baptism V. The Icon of the Lord’s Transfiguration VI. The Crucifixion Icon VII. The Icons of Christ’s Resurrection VIII. The Ascension Icon IX. The Pentecost Icon X. The Icon of Divine Wisdom Section I Beauty CHAPTER ONE The Biblical Vision of Beauty “Beauty is the splendor of truth.” So said Plato in an affirmation that the genius of the Greek language completed by coining a single term, kalokagathia. -

Bcsfazine #527 | Felicity Walker

The Newsletter of the British Columbia Science Fiction Association #527 $3.00/Issue April 2017 In This Issue: This and Next Month in BCSFA..........................................0 About BCSFA.......................................................................0 Letters of Comment............................................................1 Calendar...............................................................................8 News-Like Matter..............................................................13 Fiction: Long Night’s Dreaming (Michael Bertrand).......19 Zeitgemässe Tanka (Kathleen Moore)............................21 Art Credits..........................................................................22 BCSFAzine © April 2017, Volume 45, #4, Issue #527 is the monthly club newsletter published by the British Columbia Science Fiction Association, a social organiza- tion. ISSN 1490-6406. Please send comments, suggestions, and/or submissions to Felicity Walker (the editor), at felicity4711@ gmail .com or Apartment 601, Manhattan Tower, 6611 Coo- ney Road, Richmond, BC, Canada, V6Y 4C5 (new address). BCSFAzine is distributed monthly at White Dwarf Books, 3715 West 10th Aven- ue, Vancouver, BC, V6R 2G5; telephone 604-228-8223; e-mail whitedwarf@ deadwrite.com. Single copies C$3.00/US$2.00 each. Cheques should be made pay- able to “West Coast Science Fiction Association (WCSFA).” This and Next Month in BCSFA Sunday 16 April at 7 PM: April BCSFA meeting—at Ray Seredin’s, 707 Hamilton Street (recreation room), New Westminster. Friday -

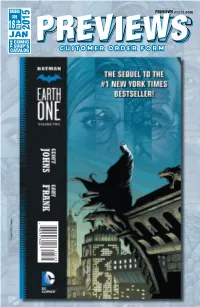

CUSTOMER ORDER FORM (Net)

ORDERS PREVIEWS world.com DUE th 18 JAN 2015 JAN COMIC THE SHOP’S PREVIEWSPREVIEWS CATALOG CUSTOMER ORDER FORM CUSTOMER 601 7 Jan15 Cover ROF and COF.indd 1 12/4/2014 3:14:17 PM Available only from your local comic shop! STAR WARS: “THE FORCE POSTER” BLACK T-SHIRT Preorder now! BIG HERO 6: GUARDIANS OF THE DC HEROES: BATMAN “BAYMAX BEFORE GALAXY: “HANG ON, 75TH ANNIVERSARY & AFTER” LIGHT ROCKET & GROOT!” SYMBOL PX BLACK BLUE T-SHIRT T-SHIRT T-SHIRT Preorder now! Preorder now! Preorder now! 01 Jan15 COF Apparel Shirt Ad.indd 1 12/4/2014 3:06:36 PM FRANKENSTEIN CHRONONAUTS #1 UNDERGROUND #1 IMAGE COMICS DARK HORSE COMICS BATMAN: EARTH ONE VOLUME 2 HC DC COMICS PASTAWAYS #1 DESCENDER #1 DARK HORSE COMICS IMAGE COMICS JEM AND THE HOLOGRAMS #1 IDW PUBLISHING CONVERGENCE #0 ALL-NEW DC COMICS HAWKEYE #1 MARVEL COMICS Jan15 Gem Page ROF COF.indd 1 12/4/2014 2:59:43 PM FEATURED ITEMS COMIC BOOKS & GRAPHIC NOVELS The Fox #1 l ARCHIE COMICS God Is Dead Volume 4 TP (MR) l AVATAR PRESS The Con Job #1 l BOOM! STUDIOS Bill & Ted’s Most Triumphant Return #1 l BOOM! STUDIOS Mouse Guard: Legends of the Guard Volume 3 #1 l BOOM! STUDIOS/ARCHAIA PRESS Project Superpowers: Blackcross #1 l D.E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT Angry Youth Comix HC (MR) l FANTAGRAPHICS BOOKS 1 Hellbreak #1 (MR) l ONI PRESS Doctor Who: The Ninth Doctor #1 l TITAN COMICS Penguins of Madagascar Volume 1 TP l TITAN COMICS 1 Nemo: River of Ghosts HC (MR) l TOP SHELF PRODUCTIONS Ninjak #1 l VALIANT ENTERTAINMENT BOOKS The Art of John Avon: Journeys To Somewhere Else HC l ART BOOKS Marvel Avengers: Ultimate Character Guide Updated & Expanded l COMICS DC Super Heroes: My First Book Of Girl Power Board Book l COMICS MAGAZINES Marvel Chess Collection Special #3: Star-Lord & Thanos l EAGLEMOSS Ace Magazine #1 l COMICS Alter Ego #132 l COMICS Back Issue #80 l COMICS 2 The Walking Dead Magazine #12 (MR) l MOVIE/TV TRADING CARDS Marvel’s Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D. -

Released 26Th August

Released 26th August DARK HORSE COMICS JUN150056 CONAN THE AVENGER #17 JUN150013 FIGHT CLUB 2 #4 MAIN MACK CVR JUN150054 HALO ESCALATION #21 JUN150079 HELLBOY IN HELL #7 APR150076 KUROSAGI CORPSE DELIVERY SERVICE OMNIBUS ED TP BOOK 01 JUN150023 MULAN REVELATIONS #3 JUN150015 NEW MGMT #1 MAIN KINDT CVR JUN150021 PASTAWAYS #6 APR150057 SUNDOWNERS TP VOL 02 JUN150022 TOMORROWS #2 APR150043 USAGI YOJIMBO SAGA LTD ED HC VOL 04 APR150042 USAGI YOJIMBO SAGA TP VOL 04 JUN150045 ZODIAC STARFORCE #1 DC COMICS JUN150176 AQUAMAN #43 JUN150241 BATGIRL #43 JUN150249 BATMAN 66 #26 JUN150247 BATMAN ARKHAM KNIGHT GENESIS #1 JUN150182 CYBORG #2 JUN150204 DEATHSTROKE #9 MAY150262 EFFIGY TP VOL 01 IDLE WORSHIP (MR) JUN150188 FLASH #43 MAY150246 GI ZOMBIE A STAR SPANGLED WAR STORY TP JUN150253 GOTHAM BY MIDNIGHT #8 JUN150255 GRAYSON #11 JUN150257 HARLEY QUINN #19 JUN150273 HE MAN THE ETERNITY WAR #9 JUN150203 JLA GODS AND MONSTERS #3 JUN150196 JUSTICE LEAGUE 3001 #3 MAY150242 JUSTICE LEAGUE DARK TP VOL 06 LOST IN FOREVER JUN150169 JUSTICE LEAGUE OF AMERICA #3 JUN150215 PREZ #3 APR150324 SCALPED HC BOOK 02 DELUXE EDITION (MR) JUN150270 SINESTRO #14 JUN150234 SUPERMAN #43 DEC140428 SUPERMAN BATMAN MICHAEL TURNER GALLERY ED HC JUN150221 TEEN TITANS #11 JUN150264 WE ARE ROBIN #3 IDW PUBLISHING JUN150439 ANGRY BIRDS COMICS HC VOL 03 SKY HIGH JUN150446 BEN 10 CLASSICS TP VOL 05 POWERLESS MAY150348 DIRK GENTLYS HOLISTIC DETECTIVE AGENCY #3 JUN150363 DRIVE #1 JUN150431 GHOSTBUSTERS GET REAL #3 JUN150375 GODZILLA IN HELL #2 MAY150423 JOE FRANKENSTEIN HC APR152727 MACHI -

1 “Bruce Wayne's Traumatic Past and Batman's New History: Ego

1 “Bruce Wayne’s Traumatic Past and Batman’s New History: Ego-Ideal and Ideal Ego in the Batman Origin Myth” Kelly Duquette Honors Thesis, Spring 2010 Director: Terry Harpold Reader: Donald Ault CONTINUOUS AND COMPLEX CHARACTERS The continuous and yet episodic nature of the superhero comic genre requires characters and storylines that can withstand the test of time. A caped, tight-wearing crusader with an affinity for theatrics can only protect the fictitious population of an equally fictitious city for so long. Eventually, storylines dry up and the hero’s sensational qualities are exhausted, unless an element of more profound significance is added which can take the character and storyline in a new direction. The modern Batman is a prime example. A handsome billionaire’s benevolence and bravery is no longer—if perhaps it ever was—enough to keep the contemporary reader interested. Such a storyline may be renovated with extreme and supernatural elements,1 but a basic problem remains: to ask the contemporary reader to continue to accept that a grown man dresses in a bat costume for altruistic reasons alone (to “fight crime,” “save his city,” etc.) is an unreasonable demand. The superhero must, like the reader, evolve over time, leaving some qualities behind and taking up new ones: the world the contemporary reader lives in, much like Gotham City, is too gritty and too complex to accept an unchanging hero. To keep readers engaged in the form—that is, to continue to generate the drama of the comic book hero—the 1 The Batman universe is home to various supervillains; for example Killer Croc, a humanoid lizard with massive strength (Detective Comics #523, 1983), or Solomon Grundy, a zombie creature who returns from the dead after being murdered and thrown into the swamp (All-American Comics #3, 1941). -

Dc Comics ---Marvel

The Sandman: Overture Secret Wars Main Series DC COMICS --------------------------- Strange Sports Stories A-Force Action Comics Suiciders Deadpool’s Secret Wars Aquaman Wolf Moon Inferno Arrow: Season 2.5 Infinity Gauntlet Batgirl Inhumans: Attilan Rising Batman MARVEL ------------------------------ M.O.D.O.K. Assassin Batman ‘66 All-New Captain America Master of Kung Fu Batman: Arkham Knight All-New Hawkeye Old Man Logan Batman/Superman All-New X-Men Planet Hulk Batman Beyond Amazing Spider-Man Secret Wars 2099 Bat-Mite Amazing X-Men Secret Wars Journal Bizarro Angela: Asgard’s Assassin Secret Wars: Battleworld Black Canary Ant-Man Spider-Verse Catwoman Avengers Ultimate End Constantine: The Hellblazer Avengers: Millenium Where Monsters Dwell Convergence Avengers Vs. Cyborg Avengers World Dark Universe Big Thunder Mountain Railroad DARK HORSE -------------------------- Deathstroke Black Widow Abe Sapien Detective Comics Bucky Barnes: Winter Soldier Angel & Faith Season 10 Doomed Captain America & Mighty Avengers Archie vs. Predator Dr. Fate Captain Marvel Baltimore: Cult of the Red King Earth 2: Society Cyclops B.P.R.D.: Hell on Earth The Flash Daredevil Captain Midnight Flash: Season 0 (TV Show) Dark Tower: House of Cards Conan the Avenger Gotham Academy Deadpool Dark Horse Presents Gotham by Midnight Return of the Living Deadpool Ei8ht Grayson Deathlok Fight Club 2 Green Arrow George Romero’s Empire of the Dead Act 3 Frankenstein Underground Green Lantern -

New Comics & TP's for the Week of 4/22/15

Guardians of Galaxy #26 Guardians of Galaxy #26 Raney Avengers Var New Comics & TP's Hulk #15 Inhuman Special #1 for the Week of 4/22/15 Ivar Timewalker #4 Justice League 3000 TP Vol 02 The Camelot War Action/13 / Adventure Loki Agent of Asgard TP Vol 02 I Cannot Tell a Lie Borderlands Fall of Fyrestone #8 MPH TP Chew #48 Ninjak #2 Complete Little Orphan Annie HC Vol 11 Solar Man of Atom #11 Deadly Class #12 Superior Iron Man Prem HC Vol 01 Infamous Drones #1 True Believers Armor Wars #1 Edward Scissorhands #7 True Believers Infinity Gauntlet #1 Empty #3 Turok Dinosaur Hunter TP Vol 02 West GI Joe A Real American Hero #213 Unbeatable Squirrel Girl #4 Godzilla Rulers of the Earth #23 Wolverines #15 Grindhouse Drive In Bleed Out #4 Wolverines TP Vol 01 Dancing with Devil Holmes vs. Houdini #5 Infinite Loop #1 Indie / Vertigo King Flash Gordon #3 Effigy #4 Lady Mechanika Tablet of Destinies #1 Scott Pilgrim Color HC Vol 06 Lady Mechanika Tablet of Destinies #1 Var Ed Suiciders #3 Lady Rawhide Lady Zorro #2 Lazarus #16 Horror Legenderry Red Sonja #3 Clive Barkers Nightbreed #12 Life After #9 Creepy Comics #20 Manifest Destiny #14 Criminal Macabre Third Child TP Miami Vice Remix #2 Fly Outbreak #2 Mind MGMT #32 GFT Little Mermaid #3 Postal #3 Satellite Sam #13 Kid’s Starling HC Ashley Wood Book 01 Adventure Time #39 Suicide Risk #24 Angry Birds #10 TMNT Color Classics Series 3 #4 Bart Simpson Blastoff TP Tomb Raider #15 Betty & Veronica Jumbo Comics Double Digest #233 Transformers Windblade Combiner Wars #2 Littlest Pet Shop Spring Cleaning Velvet #10 Marvel Universe Guardians of Galaxy #3 Zombies vs. -

Entertaining Crisis in the Atlantic Imperium, 1770–1790 O'quinn, Daniel

Entertaining Crisis in the Atlantic Imperium, 1770–1790 O'Quinn, Daniel Published by Johns Hopkins University Press O'Quinn, Daniel. Entertaining Crisis in the Atlantic Imperium, 1770–1790. Johns Hopkins University Press, 2011. Project MUSE. doi:10.1353/book.1868. https://muse.jhu.edu/. For additional information about this book https://muse.jhu.edu/book/1868 [ Access provided at 3 Oct 2021 03:51 GMT with no institutional affiliation ] This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Entertaining Crisis in the Atlantic Imperium 1770– 1790 This page intentionally left blank Entertaining Crisis in the Atlantic Imperium 1770– 1790 daniel o’quinn The Johns Hopkins University Press Baltimore © 2011 The Johns Hopkins University Press All rights reserved. Published 2011 Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper 2 4 6 8 9 7 5 3 1 The Johns Hopkins University Press 2715 North Charles Street Baltimore, Mary land 21218- 4363 www .press .jhu .edu Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data O’Quinn, Daniel, 1962– Entertaining crisis in the Atlantic imperium, 1770– 1790 / Daniel O’Quinn. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN- 13: 978- 0- 8018- 9931- 7 (hardcover : alk. paper) ISBN- 10: 0- 8018- 9931- 1 (hardcover : alk. paper) 1. En glish drama— 18th century— History and criticism. 2. Mascu- linity in literature. 3. Politics and literature— Great Britain— History—18th century. 4. Theater— England—London—History— 18th century. 5. Theater— Political aspects— England—London. 6. Press and politics— Great Britain— History—18th century. 7. United States— History—Revolution, 1775– 1783—Infl uence. -

The Beyond Heroes Roleplaying Game Book I: the Player's Guide

1 The Beyond Heroes Roleplaying Game Book XXIV: The Book of Artifacts Writing and Design: Marco Ferraro The Book of Artifacts Copyright © 2020 Marco Ferraro All Rights Reserved This is meant as an amateur free fan production. Absolutely no money is generated from it. Wizards of the Coast, Dungeons & Dragons, and their logos are trademarks of Wizards of the Coast LLC in the United States and other countries. © 2019 Wizards. All Rights Reserved. Beyond Heroes is not affiliated with, endorsed, sponsored, or specifically approved by Wizards of the Coast LLC. Contents Foreword 3 Buying Magical Items 3 Magic; rare or common? 4 Researching Magical Items 4 The Nature of Magical Fabrication 5 Scrolls and Potions 7 Creating other magical items 10 Recharging Magical Items 12 Destroying Magical Items 13 Artifacts and Relics 13 Magic Item Quick Roll Table 18 Arcane Artifact Quick Roll Table 22 Arcane Vehicle Quick Roll Table 24 Arcane Architecture Quick Roll Table 28 Mystical Materials 33 Future Materials 37 Normal Materials 37 Modern Armour 40 Materials from other universes 40 Armour Materials Table 47 Beyond Heroes Artifacts 51 DC Universe Artifacts 59 Marvel Universe Artifacts 93 Artifacts from other Comic Universes’ 119 Moorcock Artifacts 125 Dungeons and Dragons Artifacts 131 Folklore Artifacts 137 2 Intelligent creatures, on the other hand, Foreword tend to value magical items above other The Beyond Heroes Role Playing Game items of treasure. They recognize such is based on a heavily revised derivative items for what they are (unless the item version of the rules system from is very well disguised or unique) and Advanced Dungeons and Dragons 2nd take them. -

Media Release June 27, 2018 DC's SUPERMAN IMMORTALISED IN

Media Release June 27, 2018 DC’S SUPERMAN IMMORTALISED IN PURE SILVER TO CELEBRATE 80 YEARS One of the most recognizable mainstays of American pop culture, DC’s Superman, will be commemorated with a range of limited edition pure silver collectables to celebrate his 80th- anniversary milestone. Making his debut in 1938, Superman became an instant hit and has been thrilling fans with his adventures and extraordinary powers ever since. Known to many as “The Man of Steel,” he has become a universal icon. Superman is the people’s hero, fighting the never-ending battle for truth and justice. The first DC Comics Super Hero Pure Silver Miniature has just been released to celebrate Superman’s 80th Anniversary, along with a Silver Coin Note collection. The collectables are produced by Auckland based company New Zealand Mint in partnership with Warner Bros Consumer Products on behalf of DC Entertainment. Designed by 3D master sculptor Alejandro Pereira Ezcurra, with a limited worldwide production of only 1,000 casts, the miniature of Superman has a guaranteed minimum 150g pure silver and is finished with an antique silver polish. The miniature is approx. 10cm tall and the silver purity, DC Comic copyright, and unique production number are detailed on the base. The miniature stands proudly on an additional stand which features a metal plate confirming the name, series number, unique production number and New Zealand Mint authentication. It is encased in black velvet inside a high-quality Superman 80th Anniversary themed case – making this striking memento for Superman fans. The Silver Coin Note collection comes in an album that includes six 5g pure silver coin notes featuring amazing images of iconic Superman comic book covers through the ages. -

2020 Inventory Graphic Novels DC

Item Lookup Code Description SubDescription1 Quantity Price Categories 978140123807054999 100 Bullets DX ED 04 HC 1 49.99 DC Graphic Novels 978140124271854999 100 Bullets DX ED 05 HC 1 49.99 DC Graphic Novels 76194124095400111 100 Bullets Samurai TP 1 12.95 DC Graphic Novels DCD664779 100 Bullets Tp Book 02 (Mr) 1 24.99 DC Graphic Novels DCD680348 100 Bullets Tp Book 03 (Mr) 1 24.99 DC Graphic Novels 978140121781551999 52 Aftermath TP 4 Horsemen 1 19.99 DC Graphic Novels 978140121353451999 52 Tp 1 1 19.99 DC Graphic Novels 978140123089051999 99 Days HC 1 19.99 DC Graphic Novels 978140123246751799 A God Somewhere TP 1 17.99 DC Graphic Novels 978140121081651999 A Sickness In Family Hc 1 19.99 DC Graphic Novels DCDL072757 Action Comics #1000 80 Yrs HC 1 29.99 DC Graphic Novels 978140124232952499 Action Comics (N52) Hc 03 At E nd Of Days 2 24.99 DC Graphic Novels 978140125077551699 Action Comics (N52) TP 04 Hybrid 1 16.99 DC Graphic Novels 978140127357651699 Action Comics TP 03 Men of Steel 2 16.99 DC Graphic Novels 978140124688451499 Adv Of Superman Tp 1 1 14.99 DC Graphic Novels 978140125036251499 Adv Of Superman Tp 2 1 14.99 DC Graphic Novels 978140125330151699 Adv Of Superman Tp 3 1 16.99 DC Graphic Novels 978140124993951699 All Star Western TP 05 Man Out of Time 1 16.99 DC Graphic Novels 978140124253451499 Ame-Comi Girls Tp 01 1 14.99 DC Graphic Novels 978140122173751499 American Splendor TP Another Dollar 1 14.99 DC Graphic Novels 978140123334151699 American Vampire 03 TP 1 16.99 DC Graphic Novels 978140123718952499 American Vampire