Austria-Hungary, Which Broke up Into Several Countries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GOODBYE, KOCHANIE! Krakow Declined

FREE October 2008 Edition 48 krakow POST ISSN 1898-4762 www.krakowpost.com Krakow Sorry CNN, Engineer from Krakow firm kidnapped in Pakistan Krakow’s Broke >> page 4 Krakow can’t afford CNN ad Poland space More reports surface on CIA John Walczak prisons in Poland >> page 6 The city’s miserly promotional budget for this year, coupled with Feature reckless spending, have left Kra- kow broke. Krakow is the only large A guide to absentee voting Polish city that will not be advertis- in upcoming elections ing itself on CNN International to >> page 10, 11 140 million viewers. In an article in the Polish daily Property Gazeta Wyborcza, it has been re- vealed that Krakow’s authorities Where and how resigned from a gigantic advertis- to buy ing campaign for a bargain price on >> page 13 CNN International. Krakow was to show itself in several hundred ad- Sport vertising spots on the international news channel for 900 thousand Wis a cling on for Second złotys. According to CNN employ- ł ees an identical campaign on a TV Coming station with fewer viewers would >> page 14 normally cost more. Culture The weak dollar and the positive Above: The future Krakow Congress Centre, designed by Krzysztof Ingarden, is the largest edifice to approach of CNN bosses to Poland be commissioned for the city since the 1930s. See page 15 for more buildings on Krakow’s horizon. Discover Polish architecture led to budget prices being offered >> page 15 for the campaign, which has the potential of reaching 140 million viewers worldwide. CNN offered several hundred prime-time ad slots to the authorities of Krakow, life , Gda sk and Warsaw - only City Łódź ń GOODBYE, KOCHANIE! Krakow declined. -

African Masks

Gustav Klimt Slide Script Pre-slides: Focus slide; “And now, it’s time for Art Lit” Slide 1: Words We Will Use Today Mosaics: Mosaics use many tiny pieces of colored glass, shiny stones, gold, and silver to make intricate images and patterns. Art Nouveau: this means New Art - a style of decorative art, architecture, and design popular in Western Europe and the US from about 1890 to 1910. It’s recognized by flowing lines and curves. Patrons: Patrons are men and women who support the arts by purchasing art, commissioning art, or by sponsoring or providing a salary to an artist so they can continue making art. Slide 2 – Gustav Klimt Gustav Klimt was a master of eye popping pattern and metallic color. Art Nouveau (noo-vo) artists like Klimt used bright colors and swirling, flowing lines and believed art could symbolize something beyond what appeared on the canvas. When asked why he never painted a self-portrait, Klimt said, “There is nothing special about me. Whoever wants to know something about me... ought to look carefully at my pictures.” We may not have a self-portrait but we do have photos of him – including this one with his studio cat! Let’s see what we can learn about Klimt today. Slide 3 – Public Art Klimt was born in Vienna, Austria where he lived his whole life. Klimt’s father was a gold engraver and he taught his son how to work with gold. Klimt won a full scholarship to art school at the age of 14 and when he finished, he and his brothers started a business painting murals on walls and ceilings for mansions, public theatres and universities. -

Download Download

Dreams anD sexuality A Psychoanalytical Reading of Klimt’s Beethoven Frieze benjamin flyThe This essay presenTs a philosophical and psychoanalyTical inTerpreTaTion of The work of The Viennese secession arTisT, GusTaV klimT. The manner of depicTion in klimT’s painTinGs underwenT a radical shifT around The Turn of The TwenTieTh cenTury, and The auThor attempTs To unVeil The inTernal and exTernal moTiVaTions ThaT may haVe prompTed and conTribuTed To This TransformaTion. drawinG from friedrich nieTzsche’s The BirTh of Tragedy as well as siGmund freud’s The inTerpreTaTion of dreams, The arTicle links klimT’s early work wiTh whaT may be referred To as The apollonian or consciousness, and his laTer work wiTh The dionysian or The subconscious. iT is Then arGued ThaT The BeeThoven frieze of 1902 could be undersTood as a “self-porTraiT” of The arTisT and used To examine The shifT in sTylisTic represenTaTion in klimT’s oeuVre. Proud Athena, armed and ready for battle with her aegis Pallas Athena (below), standing in stark contrast to both of and spear, cuts a striking image for the poster announcing these previous versions, takes their best characteristics the inaugural exhibition of the Vienna Secession. As the and bridges the gap between them: she is softly modeled goddess of wisdom, the polis, and the arts, she is a decid- but still retains some of the poster’s two-dimensionality (“a edly appropriate figurehead for an upstart group of diverse concept, not a concrete realization”2); the light in her eyes artists who succeeded in fighting back against the estab- speaks to an internal fire that more accurately represents lished institution of Vienna, a political coup if there ever the truth of the goddess; and perhaps most importantly, 28 was one. -

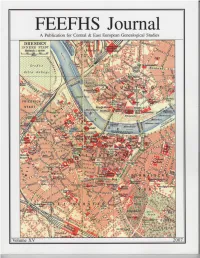

FEEFHS Journal Volume 15, 2007

FEEFHS Journal Volume 15, 2007 FEEFHS Journal Who, What and Why is FEEFHS? The Federation of East European Family History Societies Guest Editor: Kahlile B. Mehr. [email protected] (FEEFHS) was founded in June 1992 by a small dedicated group of Managing Editor: Thomas K. Edlund American and Canadian genealogists with diverse ethnic, religious, and national backgrounds. By the end of that year, eleven societies FEEFHS Executive Council had accepted its concept as founding members. Each year since then FEEFHS has grown in size. FEEFHS now represents nearly two 2006-2007 FEEFHS officers: hundred organizations as members from twenty-four states, five Ca- President: Dave Obee, 4687 Falaise Drive, Victoria, BC V8Y 1B4 nadian provinces, and fourteen countries. It continues to grow. Canada. [email protected] About half of these are genealogy societies, others are multi- 1st Vice-president: Brian J. Lenius. [email protected] purpose societies, surname associations, book or periodical publish- 2nd Vice-president: Lisa A. Alzo ers, archives, libraries, family history centers, online services, insti- 3rd Vice-president: Werner Zoglauer tutions, e-mail genealogy list-servers, heraldry societies, and other Secretary: Kahlile Mehr, 412 South 400 West, Centerville, UT. ethnic, religious, and national groups. FEEFHS includes organiza- [email protected] tions representing all East or Central European groups that have ex- Treasurer: Don Semon. [email protected] isting genealogy societies in North America and a growing group of worldwide organizations and individual members, from novices to Other members of the FEEFHS Executive Council: professionals. Founding Past President: Charles M. Hall, 4874 S. 1710 East, Salt Lake City, UT 84117-5928 Goals and Purposes: Immediate Past President: Irmgard Hein Ellingson, P.O. -

The Botanical Exploration of Angola by Germans During the 19Th and 20Th Centuries, with Biographical Sketches and Notes on Collections and Herbaria

Blumea 65, 2020: 126–161 www.ingentaconnect.com/content/nhn/blumea RESEARCH ARTICLE https://doi.org/10.3767/blumea.2020.65.02.06 The botanical exploration of Angola by Germans during the 19th and 20th centuries, with biographical sketches and notes on collections and herbaria E. Figueiredo1, *, G.F. Smith1, S. Dressler 2 Key words Abstract A catalogue of 29 German individuals who were active in the botanical exploration of Angola during the 19th and 20th centuries is presented. One of these is likely of Swiss nationality but with significant links to German Angola settlers in Angola. The catalogue includes information on the places of collecting activity, dates on which locations botanical exploration were visited, the whereabouts of preserved exsiccata, maps with itineraries, and biographical information on the German explorers collectors. Initial botanical exploration in Angola by Germans was linked to efforts to establish and expand Germany’s plant collections colonies in Africa. Later exploration followed after some Germans had settled in the country. However, Angola was never under German control. The most intense period of German collecting activity in this south-tropical African country took place from the early-1870s to 1900. Twenty-four Germans collected plant specimens in Angola for deposition in herbaria in continental Europe, mostly in Germany. Five other naturalists or explorers were active in Angola but collections have not been located under their names or were made by someone else. A further three col- lectors, who are sometimes cited as having collected material in Angola but did not do so, are also briefly discussed. Citation: Figueiredo E, Smith GF, Dressler S. -

LESSON Gustav Klimt Elements Of

LESSON 1 Gustav Klimt Elements of Art Tree of Life Verbal Directions LESSON GUSTAV KLIMT/ELEMENTS OF ART 1 KIMBALL ART CENTER & PARK CITY ED. FOUNDATION LESSON OVERVIEW Students will learn about the artist Gustav Klimt (1862–1918) and his SUPPLIES • Images of Klimt’s artwork decorative art style. Klimt was a twentieth century master of decorative showcasing elements of art. art, a visual art style known for hosting design and ornamentation of • Samples of Tree of Life. items. Students will also learn about the elements of art and how they are • Gold glitter. portrayed in Klimt’s artwork. Students will use these elements with verbal • Glue. directives to create their own “Tree of Life”, one of Klimt’s most famous • Black sharpies. works, in his decorative style. • Markers. • Metallic markers and/or INSTRUCTIONAL OBJECTIVES paint markers. • Learn about Gustav Klimt. • White or brown paper. • Learn about the elements of art and apply them in artwork. • Black construction paper for Line, Shape, Form, Value, Space, Color, Texture matting artwork. • Learn about Klimt’s decorative style of art. • Create a “Tree of Life” using elements of art in the style of Klimt. GUSTAV KLIMT Gustav Klimt (1862-1918) was an Austrian symbolist painter and his artwork was viewed as a rebellion against the traditional academic art of his time. He is noted for his highly decorative style in art most often seen in art with women with elaborate gowns, blankets and landscapes. Klimt was a co-founder of the Vienna Secessionist movement, a movement closely linked to Symbolism whereby artists tried to show truth using unrealistic or fantastical objects. -

Artist Resources – Gustav Klimt (Austrian, 1862-1918) Gustav Klimt Foundation Klimt at Neue Galerie, New York

Artist Resources – Gustav Klimt (Austrian, 1862-1918) Gustav Klimt Foundation Klimt at Neue Galerie, New York The Getty Center partnered with Vienna’s Albertina Museum in 2012 for the first retrospective dedicated to Klimt’s prolific drawing practice. Marking the 150th anniversary of his birth, the prominent collection traced Klimt’s use of the figure from the 1880s until his death. Digital resources from the Getty provide background on Klimt’s relationships to Symbolism and the Secession movement, his public murals, drawings, and late portraits. In 2015, the Neue Galerie commemorated the film, Woman in Gold, with an exhibition bringing together Klimt’s infamous portrait of Adele Bloch Bauer with a suite of historical material. Bauer’s portrait was at the nexus of a conversation about the return of Nazi looted art, now in prestigious museums, to the progeny of families they were stolen from during WWII. San Francisco’s de Young museum presented the first major exhibition of Klimt’s work on the west coast in 207, paiting the Vienna Secessionist with sculptures and works on paper by August Rodin, whom Klimt met in 1902. The Leopold museum celebrated the centennial of Klimt’s death and his contribution to Viennese modernism in a comprehensive survey in 2018. Also in 2018, the Museum of Fine Arts Boston and the Royal Academy of Art in London opened surveys exploring the creative influences of Klimt and his young mentee Egon Schiele through the medium of drawing. Klimt, 1917 In a series of talks in Boston in conjunction with the exhibition, Professor Judith Bookbinder spoke about the aesthetic differences of Klimt, Schiele, and Schiele’s contemporary Oskar Kokoschka. -

Title Japonisme in Polish Pictorial Arts (1885 – 1939) Type Thesis URL

Title Japonisme in Polish Pictorial Arts (1885 – 1939) Type Thesis URL http://ualresearchonline.arts.ac.uk/6205/ Date 2013 Citation Spławski, Piotr (2013) Japonisme in Polish Pictorial Arts (1885 – 1939). PhD thesis, University of the Arts London. Creators Spławski, Piotr Usage Guidelines Please refer to usage guidelines at http://ualresearchonline.arts.ac.uk/policies.html or alternatively contact [email protected]. License: Creative Commons Attribution Non-commercial No Derivatives Unless otherwise stated, copyright owned by the author Japonisme in Polish Pictorial Arts (1885 – 1939) Piotr Spławski Submitted as a partial requirement for the degree of doctor of philosophy awarded by the University of the Arts London Research Centre for Transnational Art, Identity and Nation (TrAIN) Chelsea College of Art and Design University of the Arts London July 2013 Volume 1 – Thesis 1 Abstract This thesis chronicles the development of Polish Japonisme between 1885 and 1939. It focuses mainly on painting and graphic arts, and selected aspects of photography, design and architecture. Appropriation from Japanese sources triggered the articulation of new visual and conceptual languages which helped forge new art and art educational paradigms that would define the modern age. Starting with Polish fin-de-siècle Japonisme, it examines the role of Western European artistic centres, mainly Paris, in the initial dissemination of Japonisme in Poland, and considers the exceptional case of Julian Żałat, who had first-hand experience of Japan. The second phase of Polish Japonisme (1901-1918) was nourished on local, mostly Cracovian, infrastructure put in place by the ‘godfather’ of Polish Japonisme Żeliks Manggha Jasieski. His pro-Japonisme agency is discussed at length. -

Agnieszka Yass-Alston (Jagiellonian University, Kraków)

SCRIPTA JUDAICA CRACOVIENSIA Vol. 13 (2015) pp. 121–141 doi:10.4467/20843925SJ.15.010.4232 www.ejournals.eu/Scripta-Judaica-Cracoviensia REBUILDING A DESTROYED WORLD: RUDOLF BERES – A JEWISH ART COLLECTOR IN INTErwAR KRAKÓW1 Agnieszka Yass-Alston (Jagiellonian University, Kraków) Key words: Jewish art collectors, Jewish collectors; provenance research, B’nai B’rith, Kraków, Lvov, Milanowek, Holocaust, National Museum in Kraków, Association of Friends of Fine Arts, Nowy Dziennik, Polish artists of Jewish origin, Polish art collectors of Jewish origin, Jewish her- itage in Kraków, Emil Beres, Rudolf Beres, Chaim Nachman Bialik, Maurycy Gottlieb, Jacek Malczewski, Jozef Stieglitz Abstract: Interwar Kraków was a vibrant cultural center in newly independent Poland. Jewish intelligentsia played a significant part in preservation of Krakowian culture, but also endowed art- ist and cultural institutions. In a shadow of renowned Maurycy Gottlieb, there is his great collector and promoter of his artistic oeuvre, Rudolf Beres (1884-1964). The core of the collection was in- herited from his father Emil. Rudolf, who arrived to Kraków to study law, brought these pictures with him, and with time extended the collection, not only with Maurycy Gottlieb’s artworks, but also other distinguished Polish artists. As a director of the Kraków Chamber of Commerce and Industry he played an influential role in the city and country scene. As a member ofSolidarność – Kraków B’nai Brith chapter, he was active in the cultural events and ventures in the city. He was the main force behind the famous exhibition of Maurycy Gottlieb’s of 1932 in the National Mu- seum in Kraków. -

The Album Polish Art and the Writing of Modernist Art History of Polish 19Th-Century Painting

Anna Brzyski Constructing the Canon: The Album Polish Art and the Writing of Modernist Art History of Polish 19th-Century Painting Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 3, no. 1 (Spring 2004) Citation: Anna Brzyski, “Constructing the Canon: The Album Polish Art and the Writing of Modernist Art History of Polish 19th-Century Painting,” Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 3, no. 1 (Spring 2004), http://www.19thc-artworldwide.org/spring04/284-constructing-the- canon-the-album-polish-art-and-the-writing-of-modernist-art-history-of-polish-19th-century- painting. Published by: Association of Historians of Nineteenth-Century Art Notes: This PDF is provided for reference purposes only and may not contain all the functionality or features of the original, online publication. ©2004 Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide Brzyski: The Album Polish Art and the Writing of Modernist Art History of Polish 19th-Century Painting Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 3, no. 1 (Spring 2004) Constructing the Canon: The Album Polish Art and the Writing of Modernist Art History of Polish 19th-Century Painting by Anna Brzyski In November 1903, the first issue of a new serial album, entitled Polish Art (Sztuka Polska), appeared in the bookstores of major cities of the partitioned Poland. Printed in a relatively small edition of seven thousand copies by the firm of W.L. Anczyc & Co., one of the oldest and most respected Polish language publishers, and distributed to all three partitions by the bookstores of H. Altenberg in Lvov (the album's publisher) and E. Wende & Co. in Warsaw, the album was a ground-breaking achievement. It was edited by Feliks Jasieński and Adam Łada Cybulski, two art critics with well-established reputations as supporters and promoters of modern art. -

Art Nouveau - 110 Ani În România

1 ART NOUVEAU - 110 ANI ÎN ROMÂNIA Texte de Rodica Rotărescu, Mircea Hortopan, Liliana Manoliu, Cornelia Dumitrescu, Macrina Oproiu, Corina Dumitrache şi Izabela Török. Design grafic şi fotografii de Alexandru Duţă Traducere de Irina Voicu Septembrie 2013 - Muzeul Naţional Peleş Nicio parte a acestei publicaţii nu poate fi reprodusă fără acordul scris al deţinătorilor drepturilor de autor. Toate drepturile rezervate. Vas Atelier european, circa 1900 Vase European Workshop, Early 20th century 6 SUMAR CONTENTS 8 DUBLĂ ANIVERSARE LA CASTELUL PELIŞOR DOUBLE ANNIVERSARY AT THE PELISOR CASTLE ARTA 1900 12 1900 ART 16 ART NOUVEAU ÎN CASTELUL PELIŞOR ART NOUVEAU AT THE PELISOR CASTLE 22 CASTELUL PELIŞOR - KAREL LIMAN ŞI ARHITECTURA ART NOUVEAU THE PELISOR CASTLE - KAREL LIMAN AND THE ART NOUVEAU ARCHITECTURE 42 PICTORI EUROPENI LA CURTEA REGALĂ A ROMÂNIEI EUROPEAN PAINTERS AT THE ROMANIAN ROYAL COURT 52 SOCIETATEA ,,TINERIMEA ARTISTICĂ’’ THE “ARTISTIC YOUTH” SOCIETY 62 REGINA ARTISTĂ ŞI CREAŢIA SA PLASTICĂ, MANUSCRISUL PE PERGAMENT THE ARTISTIC QUEEN AND HER PAINTING, THE PARCHMENT MANUSCRIPT 76 AFIŞUL ART NOUVEAU THE ART NOUVEAU POSTER 80 COLECŢIA DE MOBILIER A REGINEI MARIA QUEEN MARIE’S FURNITURE COLLECTION COLECŢIA DE STICLĂ A REGINEI MARIA 90 QUEEN MARIE’S GLASSWARE COLLECTION 114 ARTA METALULUI ÎN PERIOADA ART NOUVEAU METALWORKING DURING THE ART NOUVEAU PERIOD 128 SCULPTURA ART NOUVEAU ART NOUVEAU SCULPTURE 136 CERAMICA ART NOUVEAU ART NOUVEAU CERAMICS 150 CATALOG SELECTIV 7 Dubla Aniversare la Castelul Pelisor Castelul Pelişor a fost construit între anii arhimandritul Nifon, ofiţeri superiori ai Rodica Rotărescu 1899-1902, de către arhitectul ceh Karel armatei române, personalităţi din lumea Director General Liman (1855-1929) la comanda regelui politică şi culturală, numeroşi localnici. -

Hrvatski Povijesni Muzej 1. Sakupljanje Graðe 1.1

HRVATSKI POVIJESNI MUZEJ 1. SAKUPLJANJE GRA ðE 1.1. Kupnja Muzejska gra ña Hrvatskog povijesnog muzeja u 2009. godini otkupom je pove ćana za 169 inventarnih jedinica. Zbirka slika, grafika i skulptura - Ignjat Gyulai, prema portretu kojeg je naslikao Johann Peter Krafft rezao Johann Pfeiffer, bakropis, Be č, 1830., inv. br. 84523 - Nikola Zrinski, crtao Jan van der Herde, rezao Frans van den Steen, bakrorez, Be č, 1670., inv. br. 84524 - Hrvatska seljanka, crtao Franz Skarbina, rezao A. Kunz, izdao Franz Lipperherde, čelikorez, Berlin, 1876., inv. br. 86325 - Hrvatska seljanka, crtao Franz Skarbina, rezao A. Kunz, izdao Franz Lipperherde, čelikorez, Berlin, 1876., inv. br. 86326 - Hrvatski seljak, crtao Franz Skarbina, rezao A. Kunz, izdao Franz Lipperherde, čelikorez, Berlin, 1876., inv. br. 86327 - Mornar Sekuli ć sa Hvara, 1917., Artur Oskar Alexander, ulje na platnu, inv. br. 87458 - Poljska kuhinja, Czeremoszno, 1916., Artur Oskar Alexander, ulje na platnu, inv. br. 87460 - Avijati čar (Gottfried Banfield ?), 1916., Artur Oskar Alexander, ulje na platnu, inv. br. 87463 - Neutvr ñeni časnik (portret zapovjednika zra čne obrane na So či, pukovnika Kuchtea), 1916., Artur Oskar Alexander, ulje na platnu, inv. br. 87459 - Pontonski most kod Zemuna, listopad 1915., Artur Oskar Alexander, ulje na ljepenci, inv. br. 87461 - Zra čna bitka kod So če, 1916., Artur Oskar Alexander, ulje na ljepenci, inv. br. 87464 - Zra čna bitka kod Pule, 1915., Artur Oskar Alexander, ulje na ljepenci, inv. br. 87456 - Konjani čka mornari čka patrola kod Trsta, 1916. (?),Artur Oskar Alexander, ulje na ljepenci, inv. br. 87457 Stranica 1 od 57 - Zapovjednik torpedne flotile linijski kapetan Massion, Trst, 1916., Artur Oskar Alexander, ulje na platnu, inv.