Ways to Project Fertility in Europe: Perceptions of Current Practices and Outcomes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of Participants

List of participants Conference of European Statisticians 69th Plenary Session, hybrid Wednesday, June 23 – Friday 25 June 2021 Registered participants Governments Albania Ms. Elsa DHULI Director General Institute of Statistics Ms. Vjollca SIMONI Head of International Cooperation and European Integration Sector Institute of Statistics Albania Argentina Sr. Joaquin MARCONI Advisor in International Relations, INDEC Mr. Nicolás PETRESKY International Relations Coordinator National Institute of Statistics and Censuses (INDEC) Elena HASAPOV ARAGONÉS National Institute of Statistics and Censuses (INDEC) Armenia Mr. Stepan MNATSAKANYAN President Statistical Committee of the Republic of Armenia Ms. Anahit SAFYAN Member of the State Council on Statistics Statistical Committee of RA Australia Mr. David GRUEN Australian Statistician Australian Bureau of Statistics 1 Ms. Teresa DICKINSON Deputy Australian Statistician Australian Bureau of Statistics Ms. Helen WILSON Deputy Australian Statistician Australian Bureau of Statistics Austria Mr. Tobias THOMAS Director General Statistics Austria Ms. Brigitte GRANDITS Head International Relation Statistics Austria Azerbaijan Mr. Farhad ALIYEV Deputy Head of Department State Statistical Committee Mr. Yusif YUSIFOV Deputy Chairman The State Statistical Committee Belarus Ms. Inna MEDVEDEVA Chairperson National Statistical Committee of the Republic of Belarus Ms. Irina MAZAISKAYA Head of International Cooperation and Statistical Information Dissemination Department National Statistical Committee of the Republic of Belarus Ms. Elena KUKHAREVICH First Deputy Chairperson National Statistical Committee of the Republic of Belarus Belgium Mr. Roeland BEERTEN Flanders Statistics Authority Mr. Olivier GODDEERIS Head of international Strategy and coordination Statistics Belgium 2 Bosnia and Herzegovina Ms. Vesna ĆUŽIĆ Director Agency for Statistics Brazil Mr. Eduardo RIOS NETO President Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística - IBGE Sra. -

Oecd Short-Term Economic Statistics Working Party (Steswp)

OECD SHORT-TERM ECONOMIC STATISTICS WORKING PARTY (STESWP) Future evolution of short-term economic economic statistics collected and disseminated by the OECD and national agencies: summary of national comments Paper prepared by Denis Ward Statistics Directorate, OECD Submitted to the Working Party under item 10 of the draft agenda Meeting: 26 – 28 June 2006 Franqueville Room OECD Headquarters, Paris Starting at 9:30 a.m. on the first day FUTURE EVOLUTION OF SHORT-TERM ECONOMIC STATISTICS COLLECTED AND DISSEMINATED BY THE OECD AND NATIONAL AGENCIES SUMMARY OF NATIONAL COMMENTS AUSTRIA (Statistics Austria) The further evolution of STS in Austria depends on the evolution of legal request by the European Union. Priorities are the work for the revision of NACE and the change of the base year (2005=100) as they involve comprehensive conceptual changes in short-term economic statistics. Austria is concentrating on the implementation of and the compliance with the requests of the amended STS-Regulation and on the satisfaction of national user’s needs, that is: • improvements in timeliness: release of the IPI at t+55 respectively t+30 or t+40 from base 2005=100 for determined aggregates • compilation of eurozone/non-eurozone indicators, • conduct of feasibility studies concerning the variables hours worked and wages and salaries in services and conceptual work in the area of trade and services • transition to NACE Rev.2 (including methods for backcasting, new sample etc.) • new web dissemination policy • satisfaction of national needs on regional level (NUTS 2): compilation of production index on NUTS 2 level; it is planned to compile turnover and labour input indicators for NACE section H, hotels and restaurants • more advanced use of administrative data Resources for new variables (e.g. -

Celebrating the Establishment, Development and Evolution of Statistical Offices Worldwide: a Tribute to John Koren

Statistical Journal of the IAOS 33 (2017) 337–372 337 DOI 10.3233/SJI-161028 IOS Press Celebrating the establishment, development and evolution of statistical offices worldwide: A tribute to John Koren Catherine Michalopouloua,∗ and Angelos Mimisb aDepartment of Social Policy, Panteion University of Social and Political Sciences, Athens, Greece bDepartment of Economic and Regional Development, Panteion University of Social and Political Sciences, Athens, Greece Abstract. This paper describes the establishment, development and evolution of national statistical offices worldwide. It is written to commemorate John Koren and other writers who more than a century ago published national statistical histories. We distinguish four broad periods: the establishment of the first statistical offices (1800–1914); the development after World War I and including World War II (1918–1944); the development after World War II including the extraordinary work of the United Nations Statistical Commission (1945–1974); and, finally, the development since 1975. Also, we report on what has been called a “dark side of numbers”, i.e. “how data and data systems have been used to assist in planning and carrying out a wide range of serious human rights abuses throughout the world”. Keywords: National Statistical Offices, United Nations Statistical Commission, United Nations Statistics Division, organizational structure, human rights 1. Introduction limitations to this power. The limitations in question are not constitutional ones, but constraints that now Westergaard [57] labeled the period from 1830 to seemed to exist independently of any formal arrange- 1849 as the “era of enthusiasm” in statistics to indi- ments of government.... The ‘era of enthusiasm’ in cate the increasing scale of their collection. -

Rural Infant Mortality in Nineteenth Century Norway1

Rural Infant Mortality in Nineteenth Century Norway1 Gunnar Thorvaldsen uch previous research on the Norwegian mortality decline has focused on specific localities, employing databases with linked microdata. One Mgood choice is Rendalen, a parish on the Swedish border, representative of the world record low Norwegian mortality rates. The focus on the role of women, given their access to more abundant material resources towards the end of the eighteenth century, is a most interesting explanation for the declining level of infant mortality.2 Another well-researched locality is the fjord-parish Etne, south of Bergen, where infant mortality was significantly higher – also an area where the role of women is highlighted. More recent studies have been done on Asker and Bærum, south of Oslo, with infant mortality levels closer to the national average. The present article will not attempt to match these penetrating studies of well- researched rural localities, nor William Hubbard’s insights into many aspects of urban mortality.3 Rather it broadens the scope to include the whole country. My study is limited primarily to Norway’s sparsely populated rural areas, where 90 percent of the population lived in 1801, a figure that was declining towards 60 percent by 1900, when the national infant mortality rate (IMR) had fallen below ten percent.4 My basic aim is to track the development of infant mortality rates in Norway over time, and, where possible, to say something about regional differences in the proportion of children who died before they reached their first birthday. The 1 Another version of this article will also be published inStudies in Mortality Decline. -

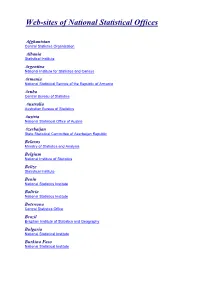

Web-Sites of National Statistical Offices

Web-sites of National Statistical Offices Afghanistan Central Statistics Organization Albania Statistical Institute Argentina National Institute for Statistics and Census Armenia National Statistical Service of the Republic of Armenia Aruba Central Bureau of Statistics Australia Australian Bureau of Statistics Austria National Statistical Office of Austria Azerbaijan State Statistical Committee of Azerbaijan Republic Belarus Ministry of Statistics and Analysis Belgium National Institute of Statistics Belize Statistical Institute Benin National Statistics Institute Bolivia National Statistics Institute Botswana Central Statistics Office Brazil Brazilian Institute of Statistics and Geography Bulgaria National Statistical Institute Burkina Faso National Statistical Institute Cambodia National Institute of Statistics Cameroon National Institute of Statistics Canada Statistics Canada Cape Verde National Statistical Office Central African Republic General Directorate of Statistics and Economic and Social Studies Chile National Statistical Institute of Chile China National Bureau of Statistics Colombia National Administrative Department for Statistics Cook Islands Statistics Office Costa Rica National Statistical Institute Côte d'Ivoire National Statistical Institute Croatia Croatian Bureau of Statistics Cuba National statistical institute Cyprus Statistical Service of Cyprus Czech Republic Czech Statistical Office Denmark Statistics Denmark Dominican Republic National Statistical Office Ecuador National Institute for Statistics and Census Egypt -

Sources and Data Description

ANNEX B ANNEX B Sources and data description User guide: List of variables Variables used Page Chapter(s) Area 147 2 Age-adjusted mortality rates based on mortality data 148 1 Death rates due to diseases of the respiratory system 148 1 Employment at place of work and gross value added by industry 149 2 Gini index of household disposable income 149 1 Gross domestic product (GDP) 150 2 Homicides 151 1 Hospital beds 152 4 Household disposable income 153 1 Households with broadband connection 154 4 Housing expenditures as a share of household disposable income 155 1 Individuals with unmet medical needs 155 1 Labour force, employment at place of residence by gender, unemployment, total and growth 156 1 and 2 Labour force by educational attainment 158 1 Life expectancy at birth, total and by gender 159 1 Life satisfaction 159 1 Local governments in metropolitan areas 160 2 Metropolitan population, total and by age 161 2 Motor vehicle theft 162 1 Municipal waste and recycled waste 163 4 Number of rooms per person 163 1 Part-time employment 164 4 Perception of corruption 164 1 PCT patent and co-patent applications, total and by sector 165 2 Physicians 165 4 PM2.5 particle concentration 166 1 Population, total, by age and gender 166 2 Population mobility among regions 167 4 R&D expenditure 169 2 R&D personnel 170 2 Social network support 170 1 Subnational government expenditure, revenue, investment and debt 171 3 Voter turnout 171 1 Young population neither in employment nor in education or training 172 4 Youth unemployment 173 4 The tables refer to the years and territorial levels used in this publication. -

European Big Data Hackathon

Teams Team: National Statistical Institute of Bulgaria - Bulgaria Sergi Sergiev National Statistical Institute of Bulgaria Valentin Chavdarov National Statistical Institute of Bulgaria Vladimir Kanchev National Statistical Institute of Bulgaria Team: Statistics Denmark - Denmark Maria Holm Statistics Denmark Niels Jespersen Statistics Denmark Olav Grøndal Statistics Denmark Team: Statistisches Bundesamt (DESTATIS) - Germany Lara Adrienne Wiengarten Statistisches Bundesamt (DESTATIS) Malte Schierholz Institute for Employment Research (IAB) Simon Rothmeier Statistisches Bundesamt (DESTATIS) Team: Statistics Estonia - Estonia Innar Liiv Tallinn University of Technology Rain Öpik DeltaBid Toomas Kirt Statistics Estonia Team: Central Statistics Office - Ireland Bruno Voisin Irish Centre for High-End Computing Eoin O'Connell Department of Justice Paul Rockley Central Statistics Office Team: Hellenic Statistical Authority - Greece Michail Mylonakis Hellenic Statistical Authority Nikolaos Bompetsis Hellenic Statistical Authority Panagiotis Vlantis Hellenic Statistical Authority Team: National Statistical Institute (INE) - Spain Jose Antonio da Rocha Padilla National Statistical Institute (INE) Luis Sanguiao Sande National Statistical Institute (INE) Miguel V. Espada University Complutense of Madrid Team: INSEE - France Benjamin Sakarovitch INSEE Stéphanie Combes INSEE Yves-Laurent Benichou INSEE 15 Feb 2017, Page 1 of 3 Team: Croatian Bureau of Statistics - Croatia Igor Kaluđer IN2data / Algebra University College Zagreb Leo Mrsic IN2data / Algebra -

Norway Health System Review

Health Systems in Transition Vol. 15 No. 8 2013 Norway Health system review Ånen Ringard • Anna Sagan Ingrid Sperre Saunes • Anne Karin Lindahl Anna Sagan (Editor), Sarah Thomson and Ewout van Ginneken were responsible for this HiT Editorial Board Series editors Reinhard Busse, Berlin University of Technology, Germany Josep Figueras, European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies Martin McKee, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, United Kingdom Elias Mossialos, London School of Economics and Political Science, United Kingdom Sarah Thomson, European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies Ewout van Ginneken, Berlin University of Technology, Germany Series coordinator Gabriele Pastorino, European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies Editorial team Jonathan Cylus, European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies Cristina Hernández-Quevedo, European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies Marina Karanikolos, European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies Anna Maresso, European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies David McDaid, European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies Sherry Merkur, European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies Philipa Mladovsky, European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies Dimitra Panteli, Berlin University of Technology, Germany Wilm Quentin, Berlin University of Technology, Germany Bernd Rechel, European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies Erica Richardson, European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies Anna Sagan, European Observatory on Health -

Report on the Implementation of the OECD Recommendation on Good Statistical Practice

Report on the Implementation of the OECD Recommendation on Good Statistical Practice 2020 2 | This report was approved by the CSSP on 26 June 2020 and prepared for publication by the OECD Secretariat. This document, as well as any data and any map included herein, are without prejudice to the status of or sovereignty over any territory, to the delimitation of international frontiers and boundaries and to the name of any territory, city or area. | 3 Executive summary 1. The Council adopted the OECD Recommendation on Good Statistical Practice [OECD/LEGAL/0417] on 23 November 2015 on a proposal of its Committee on Statistics and Statistical Policy (CSSP). It became immediately applicable to all OECD Member countries, but was also open to non-Members’ adherence (referred together as the “Adherents”). To date, five non-Members have adhered to the Recommendation: Argentina, Croatia, Peru, Romania and Bulgaria. 2. The Recommendation is the first and only OECD legal instrument concerning statistics. It represents a key reference for assessing and benchmarking national statistical systems, and a detailed blueprint to establish a sound and credible national statistical system. 3. It comprises twelve recommendations, covering: ● the institutional, legal and resource requirements for statistical systems; ● the methods and quality of processes of statistical collection, production and dissemination; and ● coordination, cooperation, and statistical innovation. 4. For each recommendation, a Set of Good Statistical Practices1 has been compiled on the basis of then existing international and national guidelines and on OECD’s experience in accession reviews. This Set of Good Statistical Practices was approved by the CSSP on 31 July 2015 and does not form an integral part of the Recommendation. -

Sources and Data Description

ANNEX B ANNEX B Sources and data description User guide: List of variables Variables used Page Area 166 Carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions 166 Concentration of PM10 particles 166 Concentration of NO2 167 Employment and gross value added by industry 167 Employment at place of work 168 Gross domestic product (GDP) 169 Infant mortality 170 Labour force, employment at place of residency, unemployment; total and by gender 171 Labour force by educational attainment 172 Land cover and changes 172 Life expectancy, total and by gender 173 Local governments in metropolitan areas 174 Long-term unemployment 175 Mortality rates due to transport accidents 175 Motor vehicle theft 176 Municipal waste and recycled waste 177 Net ecosystem productivity (NEP) 177 Number of cars 178 Number of murders 179 Number of hospital beds 180 Number of physicians 181 Part-time employment 182 PCT patent applications, total and by sector; PCT co-patent applications 182 Population; total, by age and gender 183 Population in functional urban areas 184 Population mobility among regions 185 Primary and disposable income of households 186 R&D expenditure 187 R&D personnel 188 Scientific publications and citations 188 Subnational government expenditure, revenue and debt 189 Young population neither in employment nor in education or training 189 Youth unemployment 190 The tables refer to the years and territorial levels used in this publication. The statistical data for Israel are supplied by and under the responsibility of the relevant Israeli authorities. The use of such data by the OECD is without prejudice to the status of the Golan Heights, East Jerusalem and Israeli settlements in the West Bank under the terms of international law. -

Socio-Economic Structure Measurement Dimension

Life Domain: Population, Households and Families Goal Dimension: Socio-Economic Structure Measurement Dimension: Population and Household Structure Subdimension: Household Size Indicator: A7343 Large Households Definition: Percentage of private households made up of more than four person Population: Total Country 1980 1981 1982 1983 1984 1985 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 EU-12 EU-15 EU-25 A 13,2 9,9 7,8 B 10,7 8,2 7,3 D 5,0 4,9 4,9 4,8 4,7 4,6 4,6 4,5 4,4 4,4 4,3 4,2 4,2 4,1 D-W 8,8 8,5 8,0 6,3 6,0 5,8 5,5 5,3 5,3 5,3 5,2 5,2 5,1 5,0 4,9 4,9 4,8 4,7 4,7 4,7 D-E 4,0 3,8 3,6 3,4 3,4 3,3 3,3 3,1 3,0 2,8 2,6 DK 7,8 7,5 7,1 6,8 6,4 6,0 5,8 5,5 5,3 5,1 5,0 4,9 4,9 4,9 4,9 4,9 5,1 5,1 5,2 5,2 5,3 5,4 5,4 5,5 5,5 E 26,4 20,3 F 11,9 9,9 8,2 7,1 FIN 8,8 8,0 6,5 6,6 6,0 5,7 6,5 GB 11,0 10,0 8,0 8,0 8,0 7,0 7,0 7,0 6,0 7,0 7,0 6,0 6,0 7,0 GR 16,5 13,3 10,6 I 14,9 11,3 IRL 32,3 30,3 26,7 22,5 19,7 17,8 17,5 N-IRL L 12,1 9,7 9,0 NL 11,8 7,0 6,8 6,7 6,6 6,5 6,5 6,5 6,4 6,4 P 18,9 15,4 9,5 S 6,3 5,5 5,2 UK 11,4 7,9 CY CZ 7,1 EE 6,0 LV LT MT H 10,5 8,1 8,7 SK SI 13,8 11,2 PL 21,0 17,1 17,4 14,1 CH 6,5 5,9 N 12,0 8,3 7,7 U.S. -

Immigrants in Norway, Sweden and Denmark There Are Very Few Good Analyses That Compare Immigration and Integration in Different Countries

Scandinavian comparative statistics on integration Immigrants in Norway, Sweden and Denmark There are very few good analyses that compare immigration and integration in different countries. Also in Scandinavia, establishing data that is of sufficiently good quality for comparisons is not without its problems. Sweden has by far the most immigrants, par- ticularly refugees, both in absolute terms and in relation to the size of the population. Labour immigration from the EU has been relatively greater in Norway than in Sweden and Denmark. The integration of immigrants is often linked to differences in the extent and composition of the immigration. Immigration on a scale experienced in the Scandinavian countries over the Silje Vatne Pettersen and last 40 years has never been seen before (see Figure 1). Some fundamental si- Lars Østby, Statistics Norway milarities have been observed in the three countries’ migration patterns, and the countries also have strong historical and cultural similarities. Neverthe- less, there are important disparities in the nature and scope of immigration that are well worth studying. The blessings of comparisons… With so many political and social similarities between the Scandinavian countries, we are as close to an experimental situation as is possible in social Data source sciences. The purpose of comparative analyses of integration of immigrants This article uses register data from in Denmark, Norway and Sweden, is to identify similarities and differences in Norway, Sweden and Denmark on the the behaviour and living conditions of immigrants in the three countries. By population’s composition, education doing so, we can form a basis for evaluating the effect of somewhat differing and labour participation.