Redalyc.JOHN B. WATSON's EARLY WORK and COMPARATIVE

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'Introspectionism' and the Mythical Origins of Scientific Psychology

Consciousness and Cognition Consciousness and Cognition 15 (2006) 634–654 www.elsevier.com/locate/concog ‘Introspectionism’ and the mythical origins of scientific psychology Alan Costall Department of Psychology, University of Portsmouth, Portsmouth, Hampshire PO1 2DY, UK Received 1 May 2006 Abstract According to the majority of the textbooks, the history of modern, scientific psychology can be tidily encapsulated in the following three stages. Scientific psychology began with a commitment to the study of mind, but based on the method of introspection. Watson rejected introspectionism as both unreliable and effete, and redefined psychology, instead, as the science of behaviour. The cognitive revolution, in turn, replaced the mind as the subject of study, and rejected both behaviourism and a reliance on introspection. This paper argues that all three stages of this history are largely mythical. Introspectionism was never a dominant movement within modern psychology, and the method of introspection never went away. Furthermore, this version of psychology’s history obscures some deep conceptual problems, not least surrounding the modern conception of ‘‘behaviour,’’ that continues to make the scientific study of consciousness seem so weird. Ó 2006 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. Keywords: Introspection; Introspectionism; Behaviourism; Dualism; Watson; Wundt 1. Introduction Probably the most immediate result of the acceptance of the behaviorist’s view will be the elimination of self-observation and of the introspective reports resulting from such a method. (Watson, 1913b, p. 428). The problem of consciousness occupies an analogous position for cognitive psychology as the prob- lem of language behavior does for behaviorism, namely, an unsolved anomaly within the domain of an approach. -

Placing Women in the History of Psychology the First American Women Psychologists

Placing Women in the History of Psychology The First American Women Psychologists Laurel Furumoto Wellesley College Elizabeth Scarborough State University of New York College at Fredonia ABSTRACT." This article presents an account of the first Traditional history has been written and interpreted by men in American women psychologists. The article provides data an androcentric frame of reference; it might quite properly be on the origins, education, marital status, and careers of described as the history of men. The very term "Women's His- the 22 women who identified themselves as psychologists tory" calls attention to the fact that something is missing from in the first edition of American Men of Science. Further, historical scholarship. (p. xiv) it explores how gender shaped their experience in relation Beyond calling attention to what is missing from the to educational and employment opportunities, responsi- history of psychology, this article begins to fill the gap by bilities to family, and the marriage versus career dilemma. sketching an overview of the lives and experiences of those Illustrations are drawn from the lives of Mary Whiton women who participated in the development of the dis- Calkins, Christine Ladd-Franklin, Margaret Floy Wash- cipline in the United States around the turn of the century. burn, and Ethel Puffer Howes. Sources used include ar- First, we identify early women psychologists. Second, we chival materials (manuscripts, correspondence, and insti- describe the women and note some comparisons between tutional records) as well as published literature. The article them and men psychologists. And last, we discuss wom- calls attention to the necessity of integrating women into en's experiences, focusing on how gender influenced their the history of the discipline if it is to provide an adequate careers. -

State of Connecticut Department of Public Health

STATE OF CONNECTICUT DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC HEALTH VERIFICATION OF DOCTORAL PROGRAM Applicant: Please complete the top portion of this form and forward it to the university where you received your doctoral degree. Name: _______________________________ Student identification number: __________________ University name and location: ________________________________________________________ TO BE COMPLETED BY EDUCATIONAL INSTITUTION ONLY The University must complete the remainder of this form for the above referenced applicant and return the form directly to the address listed below. The applicant completed a doctoral program of study within the Department of __________________ Please specify type of psychology program: clinical psychology counseling psychology school psychology other: ___________________________________________________ Was the candidate's program of study APA accredited at the time of the applicant’s completion? YES NO Did this applicant complete a course of studies encompassing a minimum of three academic years of full- time graduate study, of which a minimum of one academic year of full-time academic graduate study in psychology in residence at the institution granting the doctoral degree? YES NO Did this applicant complete coursework in scientific methods as follows (Check all that apply and indicate number of credit hours): Coursework No. of Credit Hours Research design and methodology Statistics and psychometrics Biological bases of behavior, for example, physiological psychology, comparative psychology, neuro-psychology, -

Psychological Bulletin

Vol. 19, No. 8 August, 1922 THE PSYCHOLOGICAL BULLETIN CONTRIBUTIONS TO THE HISTORY OF PSYCHOLOGY— 1916-1921 By COLEMAN R. GRIFFITH University of Illinois Contributions to the history of psychology since 1915 fall nat- urally into two groups. There are, on the one hand, the systematic and the experimental studies which have made the science six years older. There are, on the other hand, the historical and biographical notes and the large and searching retrospections which relate con- temporary psychology to earlier stages in the development of the science. It is to an enumeration of these contributions that the present paper is devoted. We cannot, of course, comment in detail upon the character of contemporary psychology, for an historian, speaking of his own times is like the Hawaiian surf-rider who seeks to judge the incoming tide from his experiences while riding a single wave; but it is possible to get a certain amount of information about the current trend of a science by considering events of various kinds which reflect or which have, presumably, influenced its general course. These events taken in conjunction with what appear, at the present moment, to be outstanding experimental and systematic studies may give a suggestion of the history of the last few years. In psychology, as well as in many other sciences, the most important event, during the period under survey, was the World War. The science of psychology was, as all know, well on the way toward complete mobilization for military purposes when the war ended. Since many of the consequences of this reorganization have not yet appeared, a detailed account of this aspect of the period must fall to a future historian. -

ICS18 - Study Questions

ICS18 - study questions January 23, 2019 1. What is the broad and what is the narrow notion of cognition? 2. What is representation? Enumenrate examples of representations considerd within different disciplines (cog. psy- chology, neuroscience, AI) and show that they fulfill the definitional requirements 3. Enumerate and characterize briefly key cognitive disciplines 4. Key theses and principles of associationism 5. How to explain a mind: pure vs mixed associationism 6. A mind according to behaviorists 7. Why is behaviorism considered “the scientific psychology”? 8. Why behaviorism (as a theory of mind) was rejected? 9. Find the elements of behaviorism within contemporary cognitive theory of mind (either symbolic or connectionist) 10. Describe Turing Machine as a computational device 11. What is computation? (remember the roll of toilet paper...) 12. The idea of a mind as a “logic machine” (McCulloch, Pitts) 13. What features does a McCulloch-Pitts neuron have? 14. What is the main difference between a McC-P neuron and a perceptron? 15. What is a model? (cf. Kenneth Craik&Minsky) 16. What are the assumptions of phrenology? 17. Localizationist view on a brain (Gall, Spurzheim) 18. Holistic approaches to human brain 19. What does it mean that some part of our body has a “topographic representation” in the brain? 20. The consequences of Broca’s and Wernicke’s discoveries for a cognitive view on a brain 21. What is Brodmann famous for? 22. What did Golgi invent? What consequences had his discovery? 23. Describe Cajal’s discoveries and their influence on neuroscience 24. The key aassumptions of the “neuron doctrine” (Cajal) 25. -

International Journal of Comparative Psychology

eScholarship International Journal of Comparative Psychology Title The State of Comparative Psychology Today: An Introduction to the Special Issue Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/0mn8n8bc Journal International Journal of Comparative Psychology, 31(0) ISSN 0889-3675 Authors Abramson, Charles I. Hill, Heather M. Publication Date 2018 License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ 4.0 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California 2018, 31 Charles Abramson Special Issue Editor Peer-reviewed* The State of Comparative Psychology Today: An Introduction to the Special Issue Charles I. Abramson 1 and Heather M. Hill 2 1 Oklahoma State University, U.S.A. 2 St. Mary’s University, U.S.A. Comparative psychology has long held an illustrious position in the pantheon of psychology. Depending on who you speak with, comparative psychology is as strong as ever or in deep decline. To try and get a handle on this the International Journal of Comparative Psychology has commissioned a special issue on the State of Comparative Psychology Today. Many of the articles in this issue were contributed by emanate comparative psychologists. The topics are wide ranging and include the importance of incorporating comparative psychology into the classroom, advances in automating, comparative cognition, philosophical perspectives surrounding comparative psychology, and issues related to comparative methodology. Of special interest is that the issue contains a listing of comparative psychological laboratories and a list of comparative psychologists who are willing to serve as professional mentors to students interested in comparative psychology. We hope that this issue can serve as a teaching resource for anyone interested in comparative psychology whether as part of a formal course in comparative psychology or as independent readings. -

Journal of Comparative Psychology Inaccessibility of Reinforcement Increases Persistence and Signaling Behavior in the Fox Squirrel (Sciurus Niger) Mikel M

Journal of Comparative Psychology Inaccessibility of Reinforcement Increases Persistence and Signaling Behavior in the Fox Squirrel (Sciurus niger) Mikel M. Delgado and Lucia F. Jacobs Online First Publication, April 14, 2016. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/com0000021 CITATION Delgado, M. M., & Jacobs, L. F. (2016, April 14). Inaccessibility of Reinforcement Increases Persistence and Signaling Behavior in the Fox Squirrel (Sciurus niger). Journal of Comparative Psychology. Advance online publication. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/com0000021 Journal of Comparative Psychology © 2016 American Psychological Association 2016, Vol. 130, No. 3, 000 0735-7036/16/$12.00 http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/com0000021 Inaccessibility of Reinforcement Increases Persistence and Signaling Behavior in the Fox Squirrel (Sciurus niger) Mikel M. Delgado and Lucia F. Jacobs University of California, Berkeley Under natural conditions, wild animals encounter situations where previously rewarded actions do not lead to reinforcement. In the laboratory, a surprising omission of reinforcement induces behavioral and emotional responses described as frustration. Frustration can lead to aggressive behaviors and to the persistence of noneffective responses, but it may also lead to new behavioral responses to a problem, a potential adaptation. We assessed the responses to inaccessible reinforcement in free-ranging fox squirrels (Sciurus niger). We trained squirrels to open a box to obtain food reinforcement, a piece of walnut. After 9 training trials, squirrels were tested in 1 of 4 conditions: a control condition with the expected reward, an alternative reinforcement (a piece of dried corn), an empty box, or a locked box. We measured the presence of signals suggesting arousal (e.g., tail flags and tail twitches) and found that squirrels performed fewer of these behaviors in the control condition and increased certain behaviors (tail flags, biting box) in the locked box condition, compared to other experimental conditions. -

Varieties of Fame in Psychology Research-Article6624572016

PPSXXX10.1177/1745691616662457RoedigerVarieties of Fame in Psychology 662457research-article2016 Perspectives on Psychological Science 2016, Vol. 11(6) 882 –887 Varieties of Fame in Psychology © The Author(s) 2016 Reprints and permissions: sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav DOI: 10.1177/1745691616662457 pps.sagepub.com Henry L. Roediger, III Washington University in St. Louis Abstract Fame in psychology, as in all arenas, is a local phenomenon. Psychologists (and probably academics in all fields) often first become well known for studying a subfield of an area (say, the study of attention in cognitive psychology, or even certain tasks used to study attention). Later, the researcher may become famous within cognitive psychology. In a few cases, researchers break out of a discipline to become famous across psychology and (more rarely still) even outside the confines of academe. The progression is slow and uneven. Fame is also temporally constricted. The most famous psychologists today will be forgotten in less than a century, just as the greats from the era of World War I are rarely read or remembered today. Freud and a few others represent exceptions to the rule, but generally fame is fleeting and each generation seems to dispense with the lessons learned by previous ones to claim their place in the sun. Keywords fame in psychology, scientific eminence, history of psychology, forgetting First, please take a quiz. Below is a list of eight names. done. (Hilgard’s, 1987, history text was better known Please look at each name and answer the following three than his scientific work that propelled him to eminence.) questions: (a) Do you recognize this name as belonging Perhaps some of you recognized another name or two to a famous psychologist? (b) If so, what area of study without much knowing why or what they did. -

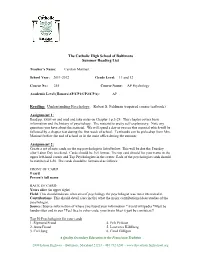

The Catholic High School of Baltimore Summer Reading List Reading

The Catholic High School of Baltimore Summer Reading List Teacher’s Name: Carolyn Marinari School Year: 2011-2012______________ Grade Level: 11 and 12 Course No.: 255 Course Name: AP Psychology Academic Level (Honors/AP/CP1/CP2/CPA): AP Reading: Understanding Psychology, Robert S. Feldman (required course textbook) Assignment 1: Read pp. xxxiv-iii and read and take notes on Chapter 1 p.3-29. This chapter covers basic information and the history of psychology. The material is pretty self-explanatory. Note any questions you have about the material. We will spend a day or two on this material which will be followed by a chapter test during the first week of school. Textbooks can be picked up from Mrs. Marinari before the end of school or in the main office during the summer. Assignment 2: Create a set of note cards on the top psychologists listed below. This will be due the Tuesday after Labor Day weekend. Cards should be 3x5 format. The top card should list your name in the upper left-hand corner and Top Psychologists in the center. Each of the psychologist cards should be numbered 1-50. The cards should be formatted as follows: FRONT OF CARD # card Person's full name BACK OF CARD Years alive (in upper right) Field: This should indicate what area of psychology the psychologist was most interested in. Contributions: This should detail (succinctly) what the major contributions/ideas/studies of the psychologist. Source: Source information of where you found your information *Avoid wikipedia *Must be handwritten and in pen *Feel free to color-code, your brain likes it-just be consistent!! Top 50 Psychologists for your cards 1. -

![Early Psychological Laboratories [1] James Mckeen Cattell (1928)](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6838/early-psychological-laboratories-1-james-mckeen-cattell-1928-936838.webp)

Early Psychological Laboratories [1] James Mckeen Cattell (1928)

Early Psychological Laboratories [1] James McKeen Cattell (1928) Classics in the History of Psychology An internet resource developed by Christopher D. Green York University, Toronto, Ontario ISSN 1492-3173 Early Psychological Laboratories [1] James McKeen Cattell (1928) First published in Science, 67, 543- 548. Posted August 2000 Laboratories for research and teaching in the sciences are of comparatively recent origin. They may be regarded as part of the industrial revolution, for there is a close parallel in causes and effects between the development of the factory system and of scientific laboratories. The industrial revolution began with the exploitation by machinery of coal and iron in England; it may perhaps be dated from the use of the steam engine of Watts in the coal mines of Cornwall about a hundred and fifty years ago. The laboratory had its origin fifty years later in Germany as part of the scientific renaissance following the Napoleonic wars. The University of Berlin was founded by Wilhelm von Humboldt and Frederich William III in 1810. The first laboratory of chemistry was opened by Justus von Liebig at Giessen in 1824. This was followed by similar laboratories at Göttingen under Wöhler in 1836, at Marburg under Bunsen in 1840, and at Leipzig under Erdmann in 1843. The first English laboratory was the College of Chemistry, now part of the Imperial College of Science and Technology of the University of London, which was opened in 1845 by von Hoffmann, brought from Germany by Prince Albert. Benjamin Silliman founded at Yale University the first American laboratory for the teaching of chemistry. -

Herrmann Collection Books Pertaining to Human Memory

Special Collections Department Cunningham Memorial Library Indiana State University September 28, 2010 Herrmann Collection Books Pertaining to Human Memory Gift 1 (10/30/01), Gift 2 (11/20/01), Gift 3 (07/02/02) Gift 4 (10/21/02), Gift 5 (01/28/03), Gift 6 (04/22/03) Gift 7 (06/27/03), Gift 8 (09/22/03), Gift 9 (12/03/03) Gift 10 (02/20/04), Gift 11 (04/29/04), Gift 12 (07/23/04) Gift 13 (09/15/10) 968 Titles Abercrombie, John. Inquiries Concerning the Intellectual Powers and the Investigation of Truth. Ed. Jacob Abbott. Revised ed. New York: Collins & Brother, c1833. Gift #9. ---. Inquiries Concerning the Intellectual Powers, and the Investigation of Truth. Harper's Stereotype ed., from the second Edinburgh ed. New York: J. & J. Harper, 1832. Gift #8. ---. Inquiries Concerning the Intellectual Powers, and the Investigation of Truth. Boston: John Allen & Co.; Philadelphia: Alexander Tower, 1835. Gift #6. ---. The Philosophy of the Moral Feelings. Boston: Otis, Broaders, and Company, 1848. Gift #8. Abraham, Wickliffe, C., Michael Corballis, and K. Geoffrey White, eds. Memory Mechanisms: A Tribute to G. V. Goddard. Hillsdale, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1991. Gift #9. Adams, Grace. Psychology: Science or Superstition? New York: Covici Friede, 1931. Gift #8. Adams, Jack A. Human Memory. McGraw-Hill Series in Psychology. New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company, c1967. Gift #11. ---. Learning and Memory: An Introduction. Homewood, Illinois: The Dorsey Press, 1976. Gift #9. Adams, John. The Herbartian Psychology Applied to Education Being a Series of Essays Applying the Psychology of Johann Friederich Herbart. -

Psychology's First Award Author(S): David B. Baker and Kevin T

The Howard Crosby Warren Medal: Psychology's First Award Author(s): David B. Baker and Kevin T. Mahoney Source: The American Journal of Psychology, Vol. 118, No. 3 (Fall, 2005), pp. 459-468 Published by: University of Illinois Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/30039075 Accessed: 10-03-2018 20:29 UTC REFERENCES Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article: http://www.jstor.org/stable/30039075?seq=1&cid=pdf-reference#references_tab_contents You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms University of Illinois Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The American Journal of Psychology This content downloaded from 128.252.67.66 on Sat, 10 Mar 2018 20:29:42 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms History of Psychology RAND B. EVANS, EDITOR East Carolina University The Howard Crosby Warren Medal: Psychology's first award DAVID B. BAKER University of Akron KEVIN T. MAHONEY Slippery Rock University This article explores the development of the first major award given in American psychology, the Howard Crosby Warren Medal.