THE CHARACTER of the LANDSCAPE 2.39 the Thames

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bromley Local Studies and Archives Index to Names in the Bromley Poor Law Union Workhouse Creed Registers Surnames Beginning Wi

Bromley Local Studies and Archives Index to names in the Bromley Poor Law Union workhouse Creed Registers Surnames beginning with C 1877-1894 Admitted Name of Discharge Admission Surname Forename(s) Birth Next of Kin address from Creed informant date Reason Year Date year 1891 9 May Cadwell Jane 1871 Ellen, Woodlands, Chase-side, N BRO CE Self 7 Jul 1891 O 1891 19 Oct Campbell John 1889 Mother: Croydon Infirmary BEC CE Police 14 Oct 1891 O 1891 23 Jun Cannon Louisa 1846 SMC CE Self 26 Jun 1891 O 1893 24 May Cannon Lucy 1851 SMC CE Self 29 May 1893 O Mother: 2nd plot, Maple Road, 1893 4 Apr Carlow George 1878 Hestable (Hextable?) nr Swanley CHI CE Self 22 May 1893 Ab 1893 1 Dec Carlow Liberty 1841 Wife: Hearnes Road, St Pauls Cray SPC CE R O 30 Dec 1893 O Brother: Walter, Cherry Orchard 1890 11 Mar Carpenter George 1833 Road, Croydon CUD CE Self 8 Mar 1893 O 1893 17 Mar Carpenter George 1833 BRO CE Self Mrs Fairman, 15 Arthur Road, 1892 8 Jul Carr Charles 1860 Beckenham BEC CE Self 9 Jul 1892 D 1878 24 Jul Carreck Jane 1814 BEC CE Self 10 Jan 1891 D 1887 1 Apr Carreck John 1812 BRO CE Self 25 Jun 1891 D Friend: Mrs Haxell, 7 Sharps 1890 3 Feb Carrington William 1838 Cottage, Bromley BRO CE Self 5 Feb 1890 O Mr Carter, 11 Styles Cottages, St 1892 26 Sep Carter Betsy 1825 Rauls Cray SPC CE R O 8 Oct 1892 O Mr Carter, 1 Oak Terrace, 1891 1 Nov Carter Eliza 1841 Orpington ORP CE R O 2 Nov 1891 O 1891 27 Oct Casinells Dominie ? 1857 CHI CE Self 25 May 1893 D Brother: Lucas, 1 Chislehurst 1890 9 Dec Castle James 1849 Road, Widmore Road, Bromley -

Download Network

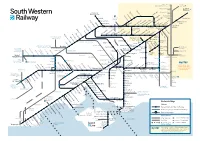

Milton Keynes, London Birmingham and the North Victoria Watford Junction London Brentford Waterloo Syon Lane Windsor & Shepherd’s Bush Eton Riverside Isleworth Hounslow Kew Bridge Kensington (Olympia) Datchet Heathrow Chiswick Vauxhall Airport Virginia Water Sunnymeads Egham Barnes Bridge Queenstown Wraysbury Road Longcross Sunningdale Whitton TwickenhamSt. MargaretsRichmondNorth Sheen BarnesPutneyWandsworthTown Clapham Junction Staines Ashford Feltham Mortlake Wimbledon Martins Heron Strawberry Earlsfield Ascot Hill Croydon Tramlink Raynes Park Bracknell Winnersh Triangle Wokingham SheppertonUpper HallifordSunbury Kempton HamptonPark Fulwell Teddington Hampton KingstonWick Norbiton New Oxford, Birmingham Winnersh and the North Hampton Court Malden Thames Ditton Berrylands Chertsey Surbiton Malden Motspur Reading to Gatwick Airport Chessington Earley Bagshot Esher TolworthManor Park Hersham Crowthorne Addlestone Walton-on- Bath, Bristol, South Wales Reading Thames North and the West Country Camberley Hinchley Worcester Beckenham Oldfield Park Wood Park Junction South Wales, Keynsham Trowbridge Byfleet & Bradford- Westbury Brookwood Birmingham Bath Spaon-Avon Newbury Sandhurst New Haw Weybridge Stoneleigh and the North Reading West Frimley Elmers End Claygate Farnborough Chessington Ewell West Byfleet South New Bristol Mortimer Blackwater West Woking West East Addington Temple Meads Bramley (Main) Oxshott Croydon Croydon Frome Epsom Taunton, Farnborough North Exeter and the Warminster Worplesdon West Country Bristol Airport Bruton Templecombe -

Acton and Chiswick Circular Trail (ACCT) – 6.5 Miles

Acton and Chiswick Circular Trail (ACCT) – 6.5 miles Acton Town Station – Gunnersbury Park – Strand on the Green – Gunnersbury Station – Chiswick business park - Gunnersbury Triangle Wildlife Reserve – Chiswick Park Station – Acton Green Common – Chiswick Common – Turnham Green Station – Bedford Park garden suburb - Acton Park – Churchfield Road – Crown Street - Mill Hill Road – Acton Town Station Route: Easy – mostly surfaced paths through parks and commons and quiet roads with short sections of main roads. Local Amenities: cafes, pubs, shops at several places. Toilets available at Gunnersbury Park and in some cafes/pubs and an Acton supermarket on route. Bike racks by Acton Town station and shops. Points of Interest: Gunnersbury Park – historic house, museum and park; the new Brentford Football Stadium; Strand on the Green on the Thames with historic houses; the landscaped Chiswick Business Park; London Wildlife Trust’s reserve at Gunnersbury; the garden suburb of Bedford Park; and Acton Park. Transport: Acton Town Station (Piccadilly and District) and local buses. Join or drop out at Kew Bridge rail station or Gunnersbury, Chiswick Park or Turnham Green tube stations. Starting at Acton Town Station. Turn left out of the station and walk past cafes and shops to cross the busy North Circular Road (A406) at lights. Continue ahead on Popes Lane to turn left into Gunnersbury Park (1), walk down the drive and turn 2nd right by a children’s playground, the café & toilets. Before the boating lake, turn left down a path by the side of the house to the Orangery. At the Orangery turn left to walk round the far side of the Horseshoe Lake. -

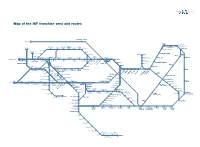

IKF ITT Maps A3 X6

51 Map of the IKF franchise area and routes Stratford International St Pancras Margate Dumpton Park (limited service) Westcombe Woolwich Woolwich Abbey Broadstairs Park Charlton Dockyard Arsenal Plumstead Wood Blackfriars Belvedere Ramsgate Westgate-on-Sea Maze Hill Cannon Street Erith Greenwich Birchington-on-Sea Slade Green Sheerness-on-Sea Minster Deptford Stone New Cross Lewisham Kidbrooke Falconwood Bexleyheath Crossing Northfleet Queenborough Herne Bay Sandwich Charing Cross Gravesend Waterloo East St Johns Blackheath Eltham Welling Barnehurst Dartford Swale London Bridge (to be closed) Higham Chestfield & Swalecliffe Elephant & Castle Kemsley Crayford Ebbsfleet Greenhithe Sturry Swanscombe Strood Denmark Bexley Whitstable Hill Nunhead Ladywell Hither Green Albany Park Deal Peckham Rye Crofton Catford Lee Mottingham New Eltham Sidcup Bridge am Park Grove Park ham n eynham Selling Catford Chath Rai ngbourneT Bellingham Sole Street Rochester Gillingham Newington Faversham Elmstead Woods Sitti Canterbury West Lower Sydenham Sundridge Meopham Park Chislehurst Cuxton New Beckenham Bromley North Longfield Canterbury East Beckenham Ravensbourne Brixton West Dulwich Penge East Hill St Mary Cray Farnigham Road Halling Bekesbourne Walmer Victoria Snodland Adisham Herne Hill Sydenham Hill Kent House Beckenham Petts Swanley Chartham Junction uth Eynsford Clock House Wood New Hythe (limited service) Aylesham rtlands Bickley Shoreham Sho Orpington Aylesford Otford Snowdown Bromley So Borough Chelsfield Green East Malling Elmers End Maidstone -

London Low Emission Zone – Impacts Monitoring, Baseline Report

Appendix 5: Air quality monitoring networks Appendix 5: Air quality monitoring networks Greater London has well over 100 air quality monitoring sites that are currently in operation, most of which are owned by local authorities and are part of the London Air Quality Network (LAQN). Defra also has a number of monitoring sites in London, which are part of the UK’s automatic network. Figure A5.1 shows the distribution of these monitoring sites in London. This appendix summarises the different monitoring networks and outlines which monitoring sites have been used for the analysis undertaken in this report, results of which are discussed in sections 8 and 10. Figure A5.1 Location of monitoring sites currently in operation in Greater London. A5.1 London Air Quality Network (LAQN) The LAQN is facilitated by London Council’s on behalf of the London boroughs who fund the equipment. The network is operated and managed by Kings College London and real-time data is available at www.londonair.org.uk. Table A5.1 lists the LAQN sites which are currently in operation in London. Impacts Monitoring – Baseline Report: July 2008 1 Appendix 5: Air quality monitoring networks Table A5.1 List of operating London Air Quality Network sites in London (as of end 2007). Borough and site name Site classification Barking & Dagenham 1 Rush Green suburban Barking & Dagenham 2 Scrattons Farm suburban Barking & Dagenham 3 North Street roadside Barnet 1 Tally Ho Corner kerbside Barnet 2 Finchley urban background Bexley 1 Slade Green suburban Bexley 2 Belvedere suburban -

Bexley Growth Strategy

www.bexley.gov.uk Bexley Growth Strategy December 2017 Bexley Growth Strategy December 2017 Leader’s Foreword Following two years of detailed technical work and consultation, I am delighted to present the Bexley Growth Strategy that sets out how we plan to ensure our borough thrives and grows in a sustainable way. For centuries, Bexley riverside has been a place of enterprise and endeavour, from iron working and ship fitting to silk printing, quarrying and heavy engineering. People have come to live and work in the borough for generations, taking advantage of its riverside locations, bustling town and village centres and pleasant neighbourhoods as well as good links to London and Kent, major airports, the Channel rail tunnel and ports. Today Bexley remains a popular place to put down roots and for businesses to start and grow. We have a wealth of quality housing and employment land where large and small businesses alike are investing for the future. We also have a variety of historic buildings, neighbourhoods and open spaces that provide an important link to our proud heritage and are a rich resource. We have great schools and two world-class performing arts colleges plus exciting plans for a new Place and Making Institute in Thamesmead that will transform the skills training for everyone involved in literally building our future. History tells us that change is inevitable and we are ready to respond and adapt to meet new opportunities. London is facing unprecedented growth and Bexley needs to play its part in helping the capital continue to thrive. But we can only do that if we plan carefully and ensure we attract the right kind of quality investment supported by the funding of key infrastructure by central government, the Mayor of London and other public bodies. -

Street Name Tree Species/Job Instructions Location Ward ALBURY AVENUE Carpinius Betulus Fastigiata Plant in Grass Verge Outside

Street Name Tree Species/Job Instructions Location Ward Carpinius betulus fastigiata plant Isleworth and ALBURY AVENUE in grass verge Outside 3-5 Brentford Area Carpinus bet.Fastigiata(clear stem) plant in excisting tree pit, Isleworth and ALBURY AVENUE grub out dead sampling. Os 12-14 Brentford Area Plant Sorbus thur. Fastigiata opposite 10 and install new tree ALKERDEN ROAD pit Os 04/06 Chiswick Area Plant Sorbus thur. Fastigiata and ALKERDEN ROAD install new tree pit Os 4-6 Chiswick Area Plant a Sorbus thur. Fastigiata opposite 10 and install new tree ALKERDEN ROAD pit Os 10 Chiswick Area Please plant new Prunus maackii on excisting grass O/S 16 on the O/S 16 on the green plant new Heston and ALMORAH ROAD green Prunus maackii Cranford Area Please plant new Prunus maackii O/S 17 plant new Prunus Heston and ALMORAH ROAD tree on excisting grass O/S 17 maackii tree on excisting grass Cranford Area O/S 21 please plant new O/S 21 Please plant new Prunus Prunus maackii tree on the Heston and ALMORAH ROAD maackii tree on the green grass on the green Cranford Area Please plant new Prunus maackii tree O/S 20-21 on the green on O/S 20-21Please plant new Heston and ALMORAH ROAD excisting grass Prunus maackii tree on grass Cranford Area Please plant new Prunus maackii on excisting grass O/S 16 on the O/S 16 on the green plant new Heston and ALMORAH ROAD green Prunus maackii Cranford Area Transplant Prunus maackii centrally in excisting grass verge O/S 17-21. -

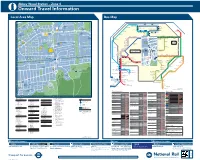

Abbey Wood Station – Zone 4 I Onward Travel Information Local Area Map Bus Map

Abbey Wood Station – Zone 4 i Onward Travel Information Local Area Map Bus Map 45 1 HARTSLOCK DRIVE TICKFORD CLOSE Y 1 GROVEBURY ROAD OAD 16 A ALK 25 River Thames 59 W AMPLEFORTH R AMPLEFORTH ROAD 16 Southmere Central Way S T. K A Crossway R 1 B I N S E Y W STANBROOK ROAD TAVY BRIDGE Linton Mead Primary School Hoveton Road O Village A B B E Y W 12 Footbridge T H E R I N E S N SEACOURT ROAD M E R E R O A D M I C H A E L’ S CLOSE A S T. AY ST. MARTINS CLOSE 1 127 SEWELL ROAD 1 15 Abbey 177 229 401 B11 MOUNTJOYCLOSE M Southmere Wood Park ROAD Steps Pumping GrGroroovoveburyryy RRoaadd Willow Bank Thamesmead Primary School Crossway Station W 1 Town Centre River Thames PANFIE 15 Central Way ANDW Nickelby Close 165 ST. HELENS ROAD CLO 113 O 99 18 Watersmeet Place 51 S ELL D R I V E Bentham Road E GODSTOW ROAD R S O U T H M E R E L D R O A 140 100 Crossway R Gallions Reach Health Centre 1 25 48 Emmanuel Baptist Manordene Road 79 STANBROOK ROAD 111 Abbey Wood A D Surgery 33 Church Bentham Road THAMESMEAD H Lakeside Crossway 165 1 Health Centre Footbridge Hawksmoor School 180 20 Lister Walk Abbey Y GODSTOW ROAD Footbridge N1 Belvedere BUR AY Central Way Wood Park OVE GROVEBURY ROAD Footbridge Y A R N T O N W Y GR ROAD A Industrial Area 242 Footbridge R Grasshaven Way Y A R N T O N W AY N 149 8 T Bentham Road Thamesmead 38 O EYNSHAM DRIVE Games N Southwood Road Bentham Road Crossway Crossway Court 109 W Poplar Place Curlew Close PANFIELD ROAD Limestone A Carlyle Road 73 Pet Aid Centre W O LV E R C O T E R O A D Y 78 7 21 Community 36 Bentham Road -

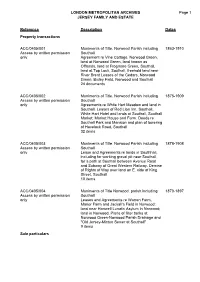

Open a PDF List of This Collection

LONDON METROPOLITAN ARCHIVES Page 1 JERSEY FAMILY AND ESTATE ACC/0405 Reference Description Dates Property transactions ACC/0405/001 Muniments of Title. Norwood Parish including 1863-1910 Access by written permission Southall only Agreement re Vine Cottage, Norwood Green, land at Norwood Green, land known as Offlands, land at Frogmore Green, Southall, land at Top Lock, Southall, freehold land near River Brent Leases of the Cedars, Norwood Green, Bixley Field, Norwood and Southall 24 documents ACC/0405/002 Muniments of Title. Norwood Parish including 1875-1909 Access by written permission Southall only Agreements re White Hart Meadow and land in Southall. Leases of Red Lion Inn, Southall, White Hart Hotel and lands at Southall, Southall Market, Market House and Farm. Deeds re Southall Park and Mansion and plan of lowering of Havelock Road, Southall 32 items ACC/0405/003 Muniments of Title. Norwood Parish including 1878-1908 Access by written permission Southall only Lease and Agreements re lands in Southhall, including for working gravel pit near Southall, for a path at Southall between Avenue Road and Subway of Great Western Railway. Demise of Rights of Way over land on E. side of King Street, Southall 10 items ACC/0405/004 Muniments of Title Norwood. parish including 1870-1897 Access by written permission Southall only Leases and Agreements re Warren Farm, Manor Farm and Jackall's Field in Norwood; land near Hanwell Lunatic Asylum in Norwood; land in Norwood. Plans of filter tanks at Norwood Green-Norwood Parish Drainage and "Old Jersey-Minton Sewer at Southall" 9 items Sale particulars LONDON METROPOLITAN ARCHIVES Page 2 JERSEY FAMILY AND ESTATE ACC/0405 Reference Description Dates ACC/0405/005 Muniments of Title Norwood Parish including 1903-1930 Access by written permission Southall only Sales Particulars - including properties in Southall, Norwood Green, Lampton, Osterley and Hanwell. -

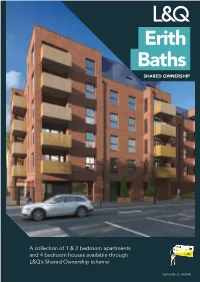

Erith Baths SHARED OWNERSHIP

Erith Baths SHARED OWNERSHIP A collection of 1 & 2 bedroom apartments and 4 bedroom houses available through L&Q’s Shared Ownership scheme lqpricedin.co.uk/erith L&Q at Erith Baths London Borough Erith Baths Vital statistics of Bexley NEW HOMES ECOLOGY AREA 15 24 5 1 bedroom 2 bedroom 4 bedroom Surrounded by open space apartments apartments houses and Riverside walks PEDESTRIAN AND EAT & DRINK CYCLE ROUTES 15 Safe pedestrian and cycle routes Restaurants and pubs nearby WELL SUPERMARKETS CONNECTED Erith overground From nearby 3 mins walk* Abbey Wood Computer generated image of L&Q at Erith Baths Belvedere overground overground 9 mins drive* Running Dec 2019 3Major supermarket retailers A home by the river Located close by the Thames, on the site of Erith’s old swimming baths, this brand new development of apartments and mews houses offers you an exceptional opportunity to get onto the property ladder. Erith Baths delivers everything you need for All homes have a balcony or other outside space, contemporary urban living. The homes are equipped there are ample storage areas and the entire building with streamlined, fully equipped kitchens, spacious benefits from advanced eco features. open plan living areas and modern bathrooms. 2 Times taken from tfl.gov.uk. 3 ERITH BELVEDERE 3 mins walk 9 mins drive Abbey Wood 5 mins Abbey Wood 3 mins Woolwich Arsenal 12 mins Dartford 15 mins London Cannon Street 37 mins Barnehurst 16 mins London Bridge 38 mins Crayford 21 mins London Charing Cross 47 mins London Charing Cross 44 mins London Liverpool Street 53 mins CROSSRAIL From nearby Abbey Wood station. -

Consultation Proposals 2020

www.bexley.gov.uk Changes to Library Services Consultation Proposals 2020 Introduction Bexley has six Council-managed libraries (Central (Bexleyheath), Crayford, Erith, Sidcup, Thamesmead, Welling) and six community managed libraries (Bexley Village, Blackfen, Bostall, North Heath, Slade Green and Upper Belvedere). The Council is considering options to change the way we operate our libraries in order to reduce costs and respond to changing customer usage patterns, whilst continuing to provide a comprehensive and efficient library service. This document sets out a range of proposed options for changes to the Library Service that will reduce the cost of the service, as part of the Council’s response to its challenging financial position, whilst ensuring that the level of service provided is in keeping with the Council’s statutory obligation to deliver library services that meet local needs. The options have been suggested following a detailed Needs Assessment undertaken by the Council which includes an analysis of usage; changes in service demand and patterns of customer behaviour over recent years; and technical innovation/new ways of working developed during the Coronavirus pandemic. The options outlined below take account of the data available to the Council about use of libraries and community need. The Needs Assessment that has informed the proposed options can be viewed in libraries, viewed online at www.bexley.gov.uk/consultations or provided by post upon written request. An Equalities Impact Assessment has also been undertaken by the Council (which forms part of the Needs Assessment) in order to ascertain the likely impact of the options being considered by the Council on those with protected characteristics (such as those with disabilities etc) and the measures which can be introduced to mitigate or reduce impact wherever possible. -

1.0 Site 1.1 Liddle Keen & Co

References – L/676/5/436 & P/2003/3749 Isleworth and Brentford Area Committee 04 March 2004 Case Officer – [email protected] - (020 8583 4943) 1.0 SITE 1.1 LIDDLE KEEN & CO, RAILSHEAD ROAD, ISLEWORTH (London Borough of Richmond, affecting Isleworth Ward) 2.0 PROPOSAL 2.1 Demolition of existing buildings, new development comprising of 18 residential units (9 private dwellings and 9 affordable flats) 2.2 The application has been called into area committee by Councillor Hibbs. The reason given is that this is an environmentally sensitive Thames Riverside area, which should be protected. 3.0 SITE DESCRIPTION: 3.1 The site is located within the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames, and is on the south side of the River Crane at its confluence with the Thames. The Richmond Road traffic bridge passes over the Crane on the western boundary of the site. Land on the northern side of the river is within the London Borough of Hounslow, and comprises the Nazareth House convent and care home complex, and also has the Isleworth Sea Scouts base. This site is within the Isleworth Riverside Conservation Area. A boat shed and dock area is directly opposite the application site. 3.2 The application site is currently used as the headquarters of a building company, and contains offices and storage areas. 4.0 HISTORY: 4.1 L/676/5/429 – Demolition of existing buildings and erection of a new building comprising 18 residential units (9 private dwellings and 9 affordable flats). The Council raised no objection to this application.