Forecasting Disaster-Related Expenses

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Landslides and Flooding

2017/11/17 Welcome Delegates to the 53rd CCOP Annual Session!!! October 16 – 19, 2017 “The Role of Geosciences in Safeguarding Our Environment” 1 2017/11/17 Cebu City 2 2017/11/17 Geohazard Information: An Indispensable Tool for Land Use Planning and Disaster Risk Resiliency Implementation RD LEO VAN V. JUGUAN Mines and Geosciences Bureau 6 53rd CCOP Annual Session October 2017 Philippine Setting Prone to GEOHAZARDS 3 2017/11/17 Porphyry Cu belts Philippines Porphyry Cu belts • Within the Ring of Fire • Within the Earthquake Belt • Within the Pacific belt of tropical cyclone (average of 20 TYPHOONS A YEAR) 4 2017/11/17 Tectonic Map of the Philippines Source: PHIVOLCS Negros Oriental Earthquake 5 2017/11/17 1:50,000 SCALE GEOHAZARD MAPPING AND ASSESSMENT (2005-2010) The National Geohazard Assessment and Geohazard Mapping Program of the DENR Mines and Geosciences Bureau mandated the conduct of a geohazard mapping for the country as included in the Medium Term Philippine Development Plan of 2004-2010. HIGHHIGH LANDSLIDEFLOOD SUSCEPTIBILITY SUSCEPTIBILITYAreas likely to experience flood heights Unstableof 1.0 to areas,2.0 meters highly and/or susceptible flood to duration mass movementof more than. 3 days. These areas are immediately flooded during heavy rains of several hours. MODERATE LANDSLIDE SUSCEPTIBILITYMODERATE FLOOD SUSCEPTIBILITY StableAreas likelyareas to with experience occasional flood or localizedheights of to mass0.5 to movement. 1.0 meters and/or flood duration of 1 to 3 days. LOWLOW FLOODLANDSLIDE SUSCEPTIBILITY SUSCEPTIBILITYAreas likely to experience flood heights of <0.5 meter and/or flood duration of less Stable areas with no identified than 1 day. -

Cost of Doing Business in the Province of Iloilo 2017 1

COST OF DOING BUSINESS IN THE PROVINCE OF ILOILO 2017 Cost of Doing Business in the Province of Iloilo 2017 1 2 Cost of Doing Business in the Province of Iloilo 2017 F O R E W O R D The COST OF DOING BUSINESS is Iloilo Provincial Government’s initiative that provides pertinent information to investors, researchers, and development planners on business opportunities and investment requirements of different trade and business sectors in the Province This material features rates of utilities, such as water, power and communication rates, minimum wage rates, government regulations and licenses, taxes on businesses, transportation and freight rates, directories of hotels or pension houses, and financial institutions. With this publication, we hope that investors and development planners as well as other interested individuals and groups will be able to come up with appropriate investment approaches and development strategies for their respective undertakings and as a whole for a sustainable economic growth of the Province of Iloilo. Cost of Doing Business in the Province of Iloilo 2017 3 4 Cost of Doing Business in the Province of Iloilo 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword I. Business and Investment Opportunities 7 II. Requirements in Starting a Business 19 III. Business Taxes and Licenses 25 IV. Minimum Daily Wage Rates 45 V. Real Property 47 VI. Utilities 57 A. Power Rates 58 B. Water Rates 58 C. Communication 59 1. Communication Facilities 59 2. Land Line Rates 59 3. Cellular Phone Rates 60 4. Advertising Rates 61 5. Postal Rates 66 6. Letter/Cargo Forwarders Freight Rates 68 VII. -

Iloilo Provincial Profile 2012

PROVINCE OF ILOILO 2012 Annual Provincial Profile TIUY Research and Statistics Section i Provincial Planning and Development Office PROVINCE OF ILOILO 2012 Annual Provincial Profile P R E F A C E The Annual Iloilo Provincial Profile is one of the endeavors of the Provincial Planning and Development Office. This publication provides a description of the geography, the population, and economy of the province and is designed to principally provide basic reference material as a backdrop for assessing future developments and is specifically intended to guide and provide data/information to development planners, policy makers, researchers, private individuals as well as potential investors. This publication is a compendium of secondary socio-economic indicators yearly collected and gathered from various National Government Agencies, Iloilo Provincial Government Offices and other private institutions. Emphasis is also given on providing data from a standard set of indicators which has been publish on past profiles. This is to ensure compatibility in the comparison and analysis of information found therewith. The data references contained herewith are in the form of tables, charts, graphs and maps based on the latest data gathered from different agencies. For more information, please contact the Research and Statistics Section, Provincial Planning & Development Office of the Province of Iloilo at 3rd Floor, Iloilo Provincial Capitol, and Iloilo City with telephone nos. (033) 335-1884 to 85, (033) 509-5091, (Fax) 335-8008 or e-mail us at [email protected] or [email protected]. You can also visit our website at www.iloilo.gov.ph. Research and Statistics Section ii Provincial Planning and Development Office PROVINCE OF ILOILO 2012 Annual Provincial Profile Republic of the Philippines Province of Iloilo Message of the Governor am proud to say that reform and change has become a reality in the Iloilo Provincial Government. -

International Milkfish Workshop Conference, May 19-22, 1976, Tigbauan, Iloilo, Philippines

International Milkfish Workshop Conference, May 19-22, 1976, Tigbauan, Iloilo, Philippines Item Type book Publisher Aquaculture Department, Southeast Asian Fisheries Development Center Download date 11/10/2021 06:00:54 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/1834/40415 International Milkfish Workshop Conference, May 19- 22, 1976, Tigbauan, Iloilo, Philippines Date published: 1976 To cite this document : International Milkfish Workshop Conference, Southeast Asian Fisheries Development Center., & International Development Research Centre (Canada). (1976). International Milkfish Workshop Conference, May 19-22, 1976, Tigbauan, Iloilo, Philippines. Tigbauan, Iloilo, Philippines: Aquaculture Department, Southeast Asian Fisheries Development Center. Keywords : Milkfish culture, Conferences, Behaviour, Feeding behaviour, Ecology, Biology, Fish eggs, Fishery surveys, Ichthyoplankton surveys, Larvae, Sexual maturity, Sexual reproduction, Natural populations, Incubation, Hatching, Rearing, Larval development, Predators, Husbandry diseases, Biological stress, Fish physiology, Fishery institutions, Research institutions, Chanos chanos, Milkfish To link to this document : http://hdl.handle.net/10862/3380 Share on : PLEASE SCROLL DOWN TO SEE THE FULL TEXT This content was downloaded from SEAFDEC/AQD Institutional Repository (SAIR) - the official digital repository of scholarly and research information of the department Downloaded by: [Anonymous] On: January 17, 2019 at 11:19 AM CST Follow us on: Facebook | Twitter | Google Plus | Instagram Library & Data -

ANALYSIS of the CHARCOAL VALUE CHAIN in ILOILO CITY (Final Report)

ANALYSIS OF THE CHARCOAL VALUE CHAIN IN ILOILO CITY (Final Report) BUILDING LOW EMISSION ALTERNATIVES TO DEVELOP ECONOMIC RESILIENCE AND SUSTAINABILITY PROJECT (B-LEADERS) September 2017 This document was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). It was prepared by the Building Low Emission Alternatives to Develop Economic Resilience and Sustainability (B- LEADERS) Project implemented by RTI International for USAID Philippines. ANALYSIS OF THE CHARCOAL VALUE CHAIN IN ILOILO CITY (Final Report) BUILDING LOW EMISSION ALTERNATIVES TO DEVELOP ECONOMIC RESILIENCE AND SUSTAINABILITY PROJECT (B-LEADERS) September 2017 DISCLAIMER The author’s views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ··································································· I LIST OF TABLES ········································································ III LIST OF FIGURES ······································································ III ACRONYMS ················································································ IV EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ································································· 1 I. INTRODUCTION ································································ 4 1.1. Objectives ............................................................................................................ 6 1.2. Scope and Limitations ....................................................................................... -

To Download the PDF File

FLOATING SOLAR POWER PLANT A 200-kilowatt floating solar power plant was constructed by SN Aboitiz Power (SNAP) occupying 2,500 square meter area over the Magat Reservoir in Ramon, Isabela. Produced by the Public Affairs and Information Staff National Irrigation Administration EDSA, Diliman, Quezon City 1101 Trunklines: 929-6071 to 79 926-8090 to 91 Website: www.nia.gov.ph www.facebook.com/nia.gov.ph BIG TICKET PROJECTS TARLAC BALOG-BALOG MULTIPURPOSE PROJECT PHASE II VISION (TBBMP II) By 2022, NIA is a professional The construction of Balog-Balog High Dam and efficient irrigation agency and Reservoir with a storage capacity of contributing to the inclusive 560 MCM for irrigation, hydroelectric power growth of the country and in the generation, fishery, and flood control purposes improvement of the farmers’ stabilized irrigation supply of the existing quality of life. 12,475 hectares service area of TBBMP Phase I. QUALITY POLICY Location: Brgy. Maamot, San Jose, Province of Tarlac MISSION We commit to provide efficient, effective, Municipalities Paniqui, Ramos, Pura, and sustainable irrigation services aimed towards Covered: Tarlac City, Victoria, Gerona, Concepcion, To plan, construct, operate, the highest satisfaction of the Filipino farmers. Capas, Lapaz, and San and maintain irrigation systems Jose consistent with integrated water We strive for the attainment of our strategic themes resource management principles to of Technical and Operational Excellence, and Good Estimated Service 34,410 hectares improve agricultural productivity Governance through Partnership with the farmers Area: and increase farmers’ and other relevant interested parties. Water Source: Moriones River income. Estimated Farmer- 23,000 We abide with applicable legal and Beneficiaries: CORE international requirements. -

Binanog Dance

Gluck Classroom Fellow: Jemuel Jr. Barrera-Garcia Ph.D. Student in Critical Dance Studies: Designated Emphasis in Southeast Asian Studies Flying Without Wings: The Philippines’ Binanog Dance Binanog is an indigenous dance from the Philippines that features the movement of an eagle/hawk to the symbolic beating of bamboo and gong that synchronizes the pulsating movements of the feet and the hands of the lead and follow dancers. This specific type of Binanog dance comes from the Panay-Bukidnon indigenous community in Panay Island, Western Visayas, Philippines. The Panay Bukidnon, also known as Suludnon, Tumandok or Panayanon Sulud is usually the identified indigenous group associated with the region and whose territory cover the mountains connecting the provinces of Iloilo, Capiz and Aklan in the island of Panay, one of the main Visayan islands of the Philippines. Aside from the Aetas living in Aklan and Capiz, this indigenous group is known to be the only ethnic Visayan language-speaking community in Western Visayas. SMILE. A pair of Binanog dancers take a pose They were once associated culturally as speakers after a performance in a public space. of the island’s languages namely Kinaray-a, Akeanon and Hiligaynon, most speakers of which reside in the lowlands of Panay and their geographical remoteness from Spanish conquest, the US invasion of the country, and the hairline exposure they had with the Japanese attacks resulted in a continuation of a pre-Hispanic culture and tradition. The Suludnon is believed to have descended from the migrating Indonesians coming from Mainland Asia. The women have developed a passion for beauty wearing jewelry made from Spanish coins strung together called biningkit, a waistband of coins called a wakus, and a headdress of coins known as a pundong. -

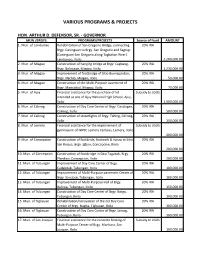

Various Programs & Projects

VARIOUS PROGRAMS & PROJECTS HON. ARTHUR D. DEFENSOR, SR. - GOVERNOR MUN./BRGYS. PROGRAMS/PROJECTS Source of Fund AMOUNT 1. Mun. of Lambunao Rehabilitation of San Gregorio Bridge, connecting 20% IRA Brgy. Caninguan to Brgy. San Gregorio and Sagcup (Caninguan-San Gregorio along Tagbakan River) Lambunao, Iloilo 2,200,000.00 2. Mun. of Miagao Construction of hanging bridge at Brgy. Cagbang- 20% IRA Brgy. Bolocaue, Miagao, Iloilo 1,230,000.00 3. Mun. of Miagao Improvement of footbridge of Sitio Buenapantao, 20% IRA Brgy. Naclub, Miagao, Iloilo 50,000.00 4. Mun. of Miagao Construction of the Multi-Purpose pavement of 20% IRA Brgy. Maricolcol, Miagao, Iloilo 70,000.00 5. Mun. of Ajuy Financial assistance for the purchase of lot Subsidy to LGUS intended as site of Ajuy National High School, Ajuy, Iloilo 1,000,000.00 6. Mun. of Calinog Construction of Day Care Center of Brgy. Caratagan, 20% IRA Calinog, Iloilo 500,000.00 7. Mun. of Calinog Construction of streetlights of Brgy. Tahing, Calinog, 20% IRA Iloilo 150,000.00 8. Mun. of Lemery Financial assistance for the improvement of Subsidy to LGUS gymnasium of NIPSC Lemery Campus, Lemery, Iloilo 400,000.00 9. Mun. of Concepcion Construction of footbride, footwalk & riprap at Sitio 20% IRA San Roque, Brgy. Igbon, Concepcion, Iloilo 200,000.00 10. Mun. of Concepcion Construction of footbridge in Sitio Tagabak, Brgy. 20% IRA Plandico, Concepcion, Iloilo 200,000.00 11. Mun. of Tubungan Improvement of Day Care Center of Brgy. 20% IRA Cadabdab, Tubungan, Iloilo 100,000.00 12. Mun. of Tubungan Improvement of Multi-Purpose pavement Center of 20% IRA Brgy. -

Infrastructure

Infrastructure Php 3,968.532 M Roads & Bridges Php 2,360.126 M Sch bldgs/classrooms Php 958.116 M Electrical Facilities 297.400 M Health Facilities and Others Php 352.891M Cost of Assistance Provided by Government Agencies/LGUs/NGOs (TAB E) NDCC - Php 16,233,375 DSWD - Php 26,018,019 DOH - Php 15,611,099 LGUs - Php 19,874,903 NGOs - Php 2,595,130 TOTAL - Php 80,332,527 International and Local Assistance/Donations (Tab F) Total International/Donations Cash - US $ 510,000 Aus $ 500,000. In kind - Php 8,000,000 (generator sets, and other non-food items NFI’s) US $ 650,000 (relief flight) Local Assistance/Donations Cash - Php 1,025,000 In Kind - Php 95,539 (assorted relief commodities) 90 sets disaster kits Areas Declared under a State of Calamity by their respective Sanggunians : 10 Provinces Albay, Antique, Iloilo, Aklan, Capiz, Sarangani, Sultan Kudarat, North Cotabato, Marinduque and Romblon 8 Municipalities Paombong and Obando in Bulacan; Carigara, Leyte; and Lake Sebu, Surallah, Sto. Nino and Tiboli in South Cotabato, and San Fernando, Romblon 3 Cities Cotabato City, Iloilo City and Passi City 9 Barangays (Zamboanga City) – Vitali, Mangusu, San Jose Gusu, Tugbungan, Putik, Baliwasan, Tumaga, Sinunuc and Sta. Catalina 2 II. Actions Taken and Resources Mobilized by Agencies: Relief and Recovery Operations NDCC-OPCEN Facilitated release of 17,790 sacks of rice in 11 regions (I – 200, III – 950, IV-A – 1,300, IV-B – 1,150, V – 250, VI – 11,300, VII – 500, VIII – 500, XII – 740, NCR – 300, ARMM – 600) amounting to P16,233,375.00 AFP-PAF Disaster Response Transported the 15 th sortie (assorted goods and medicine boxes) from DZRH & PAGCOR to Iloilo III. -

Weather Observation at Tigbauan, Iloilo, Philippines from 1977 to 1980

Technical eportR No. 8 March 1981 Weather Observation at Tigbauan, Iloilo, Philippines From 1977 to 1980 Hiroshi Motoh, Noel Solis, Edna Caligdong Milagros Gelangre and Fely Boblo AQUACULTURE DEPARTMENT SOUTHEAST ASIAN FISHERIES DEVELOPMENT CENTER Tigbauan, Iloilo, Philippines Weather Observations at Tigbauan, Iloilo, Philippines, From 1977 to 1980 Hiroshi Motoh, Noel Solis, Edna Caligdong, Milagros Gelangre and Fely Boblo INTRODUCTION The Philippines lies in the tropic region from approximately 5 to 19°N latitude. The weather condition is relatively constant compared with countries in the temperate zone such as Japan. However, through careful observations, there is a slight difference in such weather parameter as air temperature during the monsoon season. When estab lishing and operating fishponds for bangos and sugpo culture, it is very important to know the weather conditions particularly wind direction, water temperature and the amount of rainfall, because these factors directly affect yields. Weather observation was initiated aiming at the following purposes: i) Train technical staff of Aquaculture Department (AQD) of the SEAFDEC in terms of knowing the method and practice of weather observations based on the daily activity. ii) Provide the basic data of weather as well as sea conditions which are necessary for the proper operation of various hatcheries, pond and cage design-construction and operation, and for the ecological study of com mercially important marine species. iii) Gather meteorological data through actual daily observations for the basic study such as those needed by students in the university. MATERIAL AND METHOD Daily weather observation was preliminarily initiated on the middle of June 1977 to familiarize the staff members who were scheduled to conduct the daily observations. -

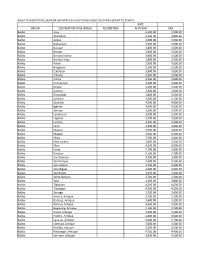

Point to Point Pick Up/Drop Off Rates Kalibo to Any

POINT TO POINT PICK UP/DROP OFF RATES KALIBO TO ANY POINT OF PANAY (POINT TO POINT) RATE ORIGIN DESTINATION (VISE VERSA) KILOMETERS AUV/VAN CAR Kalibo Ajuy 4,200.00 3,900.00 Kalibo Alimodian 4,100.00 3,800.00 Kalibo Anilao 4,000.00 3,700.00 Kalibo Badiangan 3,900.00 3,600.00 Kalibo Balasan 3,800.00 3,500.00 Kalibo Banate 3,800.00 3,500.00 Kalibo Barotac Nuevo 3,900.00 3,600.00 Kalibo Barotac Viejo 3,800.00 3,500.00 Kalibo Batad 3,900.00 3,600.00 Kalibo Bingawan 3,100.00 2,900.00 Kalibo Cabatuan 3,900.00 3,600.00 Kalibo Calinog 3,200.00 3,000.00 Kalibo Carles 4,200.00 3,900.00 Kalibo Concepcion 4,200.00 3,900.00 Kalibo Dingle 3,400.00 3,100.00 Kalibo Duenas 3,300.00 3,000.00 Kalibo Dumangas 3,800.00 3,500.00 Kalibo Estancia 4,000.00 3,700.00 Kalibo Guimbal 4,300.00 4,000.00 Kalibo Igbaras 4,600.00 4,300.00 Kalibo Janiuay 3,600.00 3,300.00 Kalibo Lambunao 3,500.00 3,200.00 Kalibo Leganes 3,700.00 3,500.00 Kalibo Lemery 3,700.00 3,400.00 Kalibo Leon 4,300.00 4,000.00 Kalibo Maasin 3,900.00 3,600.00 Kalibo Miagao 4,600.00 4,300.00 Kalibo Mina 3,700.00 3,400.00 Kalibo New Lucena 3,800.00 3,500.00 Kalibo Oton 4,300.00 4,000.00 Kalibo Pavia 3,700.00 3,400.00 Kalibo Pototan 3,700.00 3,400.00 Kalibo San Dionisio 4,200.00 3,900.00 Kalibo San Enrique 3,400.00 3,100.00 Kalibo San Joaquin 4,700.00 4,400.00 Kalibo San Miguel 4,200.00 3,900.00 Kalibo San Rafael 3,500.00 3,200.00 Kalibo Santa Barbara 3,700.00 3,400.00 Kalibo Sara 4,100.00 3,800.00 Kalibo Tigbauan 4,300.00 4,000.00 Kalibo Tubungan 4,500.00 4,200.00 Kalibo Zarraga 3,700.00 3,400.00 Kalibo -

Comprehensive Land Use Plan 2014-2024 | Municipality of Tigbauan 1 Republic of the Philippines Province of Iloilo Municipality

Republic of the Philippines Province of Iloilo Municipality of Tigbauan Office of the Sangguniang Bayan Tigbauan Municipal Hall, Tigbauan, Iloilo 5021 Philippines (033) 511-8530 [email protected] EXCERPT FROM THE MINUTES OF THE 27TH REGULAR SESSION OF THE HONORABLE SANGGUNIANG BAYAN, TIGBAUAN, ILOILO HELD AT THE S.B. SESSION HALL, TIGBAUAN MUNICIPAL BUILDING, TIGBAUAN, ILOILO ON JULY 15, 2015 AT 1:40 IN THE AFTERNOON PRESENT: HON. ROEL T. JARINA - Vice Mayor & Presiding Officer HON. JOSE DONEL T. TRASPORTO - S.B. Member HON. RENEE LIBRODO-VALENCIA - S.B. Member HON. VIRGILIO T. TERUEL - S.B. Member HON. MARLON TERUÑEZ - S.B. Member HON. MA. GERRYLIN SANTUYO-CAMPOSAGRADO - S.B. Member HON. SUZETTE MARIE HILADO-BANNO - S.B. Member HON. RICKY T. NULADA - S.B. Member HON. ARIEL I. BERNARDO - S.B. Member HON. RONNIE T. PAGUNTALAN - Liga President ABSENT: N O N E - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Municipal Ordinance No. 2015-004 AN ORDINANCE AMENDING ZONING ORDINANCE NO. 95-057, DATED OCTOBER 3, 1995 OF THE MUNICIPALITY OF TIGBAUAN, PROVINCE OF ILOILO AND PROVIDING FOR THE ADMINISTRATION, ENFORCEMENT AND AMENDMENT THEREOF AND FOR THE REPEAL OF ALL ORDINANCES IN CONFLICT THEREWITH - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -