ACAP Westland Petrel EN1.1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tinamiformes – Falconiformes

LIST OF THE 2,008 BIRD SPECIES (WITH SCIENTIFIC AND ENGLISH NAMES) KNOWN FROM THE A.O.U. CHECK-LIST AREA. Notes: "(A)" = accidental/casualin A.O.U. area; "(H)" -- recordedin A.O.U. area only from Hawaii; "(I)" = introducedinto A.O.U. area; "(N)" = has not bred in A.O.U. area but occursregularly as nonbreedingvisitor; "?" precedingname = extinct. TINAMIFORMES TINAMIDAE Tinamus major Great Tinamou. Nothocercusbonapartei Highland Tinamou. Crypturellus soui Little Tinamou. Crypturelluscinnamomeus Thicket Tinamou. Crypturellusboucardi Slaty-breastedTinamou. Crypturellus kerriae Choco Tinamou. GAVIIFORMES GAVIIDAE Gavia stellata Red-throated Loon. Gavia arctica Arctic Loon. Gavia pacifica Pacific Loon. Gavia immer Common Loon. Gavia adamsii Yellow-billed Loon. PODICIPEDIFORMES PODICIPEDIDAE Tachybaptusdominicus Least Grebe. Podilymbuspodiceps Pied-billed Grebe. ?Podilymbusgigas Atitlan Grebe. Podicepsauritus Horned Grebe. Podicepsgrisegena Red-neckedGrebe. Podicepsnigricollis Eared Grebe. Aechmophorusoccidentalis Western Grebe. Aechmophorusclarkii Clark's Grebe. PROCELLARIIFORMES DIOMEDEIDAE Thalassarchechlororhynchos Yellow-nosed Albatross. (A) Thalassarchecauta Shy Albatross.(A) Thalassarchemelanophris Black-browed Albatross. (A) Phoebetriapalpebrata Light-mantled Albatross. (A) Diomedea exulans WanderingAlbatross. (A) Phoebastriaimmutabilis Laysan Albatross. Phoebastrianigripes Black-lootedAlbatross. Phoebastriaalbatrus Short-tailedAlbatross. (N) PROCELLARIIDAE Fulmarus glacialis Northern Fulmar. Pterodroma neglecta KermadecPetrel. (A) Pterodroma -

POP2009-01 Black Petrel Foraging Presentation by Elizabeth Bell

At‐sea distribution of Black Petrel, Procellaria parkinsoni, on Great Barrier Island, Hauraki Gulf, New Zealand ELIZABETH BELL1, Joanna Sim, Leigh Torres, Scott Schaffer and Ed Abraham 1. Wildlife Management International Limited, PO Box 45, Spring Creek, Marlborough 7244, New Zealand, [email protected] BLACK PETREL RESEARCH PROJECT •Medium‐sized petrel (average 700 g) •All black (with pale sections on bill) • Endemic to New Zealand • Previously found throughout North Island and NW Nelson •On Great Barrier Island (c. 5000 birds) •On Little Barrier Island (c. 250 birds) Photo: Dave Boyle Photo: Dave Boyle BLACK PETREL RESEARCH PROJECT Great Barrier Little Barrier Island Island Auckland BLACK PETREL RESEARCH PROJECT • Breed from October to June –Adults return to the colony in mid‐October to clean burrows, pair and mate, then depart on “honeymoon” –Return to colony in late November to lay a single egg –Incubate egg for 57 days –Eggs hatch from late January through February –Chicks fledge after 107 days (from mid‐April through to late June) –Adults and chicks migrate to South America for winter BLACK PETREL RESEARCH PROJECT • Black petrels caught by commercial and recreational fishers both in New Zealand and overseas –Since 1996, 38 have been caught in NZ waters by local commercial fishers (mainly on domestic tuna long‐line and on snapper fisheries) – Anecdotal capture reports from recreational fishers –Unknown level of fisheries impact overseas BLACK PETREL RESEARCH PROJECT • Long‐term research project on Great Barrier Island (since 1995/96 breeding season) –Long‐term mark‐recapture programme – Determine baseline population dynamics, including an accurate population estimate – Determine breeding success (and causes of failures) – Determine at‐sea distribution of the Great Barrier Island black petrel population (and identify areas of risk from fisheries) – Determine population trends (including survival and recruitment) BLACK PETREL RESEARCH PROJECT Mount Hobson (Hirakimata) Study Site •Covers 35 hectares around the summit. -

Petrelsrefs V1.1.Pdf

Introduction I have endeavoured to keep typos, errors, omissions etc in this list to a minimum, however when you find more I would be grateful if you could mail the details during 2017 & 2018 to: [email protected]. Please note that this and other Reference Lists I have compiled are not exhaustive and are best employed in conjunction with other sources. Grateful thanks to Killian Mullarney and Tom Shevlin (www.irishbirds.ie) for the cover images. All images © the photographers. Joe Hobbs Index The general order of species follows the International Ornithologists' Union World Bird List (Gill, F. & Donsker, D. (eds.) 2017. IOC World Bird List. Available from: http://www.worldbirdnames.org/ [version 7.3 accessed August 2017]). Version Version 1.1 (August 2017). Cover Main image: Bulwer’s Petrel. At sea off Madeira, North Atlantic. 14th May 2012. Picture by Killian Mullarney. Vignette: Northern Fulmar. Great Saltee Island, Co. Wexford, Ireland. 5th May 2008. Picture by Tom Shevlin. Species Page No. Antarctic Petrel [Thalassoica antarctica] 12 Beck's Petrel [Pseudobulweria becki] 18 Blue Petrel [Halobaena caerulea] 15 Bulwer's Petrel [Bulweria bulweri] 24 Cape Petrel [Daption capense] 13 Fiji Petrel [Pseudobulweria macgillivrayi] 19 Fulmar [Fulmarus glacialis] 8 Giant Petrels [Macronectes giganteus & halli] 4 Grey Petrel [Procellaria cinerea] 19 Jouanin's Petrel [Bulweria fallax] 27 Kerguelen Petrel [Aphrodroma brevirostris] 16 Mascarene Petrel [Pseudobulweria aterrima] 17 Parkinson’s Petrel [Procellaria parkinsoni] 23 Southern Fulmar [Fulmarus glacialoides] 11 Spectacled Petrel [Procellaria conspicillata] 22 Snow Petrel [Pagodroma nivea] 14 Tahiti Petrel [Pseudobulweria rostrata] 18 Westland Petrel [Procellaria westlandica] 23 White-chinned Petrel [Procellaria aequinoctialis] 20 1 Relevant Publications Beaman, M. -

Black Petrel Population Status on Little Barrier Island 2014-15

DETERMINING THE POPULATION STATUS OF BLACK PETREL (PROCELLARIA PARKINSONI) ON TE HAUTURU-O-TOI/LITTLE BARRIER ISLAND Endemic to New Zealand, the black petrel (Procellaria parkinsoni) is a globally vulnerable seabird that breeds on just two islands, Te Hauturu-o-Toi/Little Barrier Island and Great Barrier Island (Aotea) in the Hauraki Gulf of northern New Zealand. Black petrels are killed in long-line and trawl fisheries within the New Zealand EEZ and overseas, with birds being caught on both recreational and commercial vessels, particularly in northern New Zealand and the Hauraki Gulf. The black petrel is recognised as the seabird species most at risk from commercial fishing activities. Along with a number of collaborators and able field assistants (many from Birds NZ) and funding support from Department of Conservation, Ministry for Primary Industries, Guardians of the Sea Charitable Trust and Birds NZ, I have had a successful season working with black petrels on Hauturu as well as Great Barrier Island/Aotea. With the assistance from the Hauturu DOC rangers Leigh Joyce and Richard Walle and their children Mahina and Liam as well as volunteers and collaborators Paul Garner-Richards, Katherine Clements, Katie Clemens-Seely, Jacob Hore, Adam Clow, Neil Fitzgerald, Simon Stoddard, Will Whittington and Ian Flux we made four visits to Hauturu over the 2014/15 black petrel breeding season. We searched for and located 90 out of the 97 historic Mike Imber black petrel study burrows on Hauturu. Only 27 of these burrows were being used by breeding black petrels. We found an additional 25 burrows along the main track bringing the number of study burrows now to 122. -

BYC-08 INF J(A) ACAP: Update on the Conservation Status

INTER-AMERICAN TROPICAL TUNA COMMISSION SCIENTIFIC ADVISORY COMMITTEE NINTH MEETING La Jolla, California (USA) 14-18 May 2018 DOCUMENT BYC-08 INF J(a) UPDATE ON THE CONSERVATION STATUS, DISTRIBUTION AND PRIORITIES FOR ALBATROSSES AND LARGE PETRELS Agreement on the Conservation of Albatrosses and Petrels (ACAP) and BirdLife International 1. STATUS AND TRENDS OF ALBATROSSES AND PETRELS Seabirds are amongst the most globally-threatened of all groups of birds, and conservation issues specific to albatrosses and large petrels led to drafting of the multi-lateral Agreement on the Conservation of Albatrosses and Petrels (ACAP). A review of the conservation status and priorities for albatrosses and large petrels was recently published in Biological Conservation (Phillips et al. 2016). There are currently 31 species listed in Annex 1 of the Agreement. Of these, 21 (68%) are classified at risk of extinction, a stark contrast to the overall rate of 12% for the 10,694 bird species worldwide (Croxall et al. 2012, Gill & Donsker 2017). Of the 22 species of albatrosses listed by ACAP, three are listed as Critically Endangered (CR), six are Endangered (EN), six are Vulnerable (VU), six are Near Threatened (NT), and one is of Least Concern (LC). Of the nine petrel species, one is listed as CR, one as EN, four as VU, one as NT and two species as LC. The population trends of ACAP species over the last twenty years (since the mid-1990s) were re-examined in 2017 by the ACAP Population and Conservation Status Working Group (PaCSWG). Thirteen ACAP species (42%) are currently showing overall population declines. -

SWFSC Archive

CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES ........................................................................................................................ ii LIST OF FIGURES ...................................................................................................................... ii INTRODUCTION......................................................................................................................... 1 OBJECTIVES ............................................................................................................................... 1 STUDY AREA AND ITINERARY ............................................................................................. 2 MATERIALS AND METHODS ................................................................................................. 3 Oceanography ............................................................................................................................. 3 Net Tows ...................................................................................................................................... 4 Acoustic Backscatter.................................................................................................................... 4 Seabirds ....................................................................................................................................... 5 Contour Plots............................................................................................................................... 5 RESULTS ..................................................................................................................................... -

Tāiko/Black Petrel and Other Seabirds

Tāiko/Black Petrel and other seabirds EDUCATION RESOURCE YEARS 5- 8 (SENIOR PRIMARY) CONTENTS Introduction Section One: The tāiko/ black petrel and other seabirds Activity 1 Meet the black petrel /tāiko Activity 2 Special features and adaptations Activity 3 Life cycle and habitat Activity 4 Finding out about seabirds Section Two: People and seabirds Activity 5 People and seabirds Activity 6 Threats to seabirds Activity 7 Experiencing seabirds in their environment Section Three: Helping seabirds Activity 8 Protection of seabirds Activity 9 It’s time to act for seabirds BLACK PETREL / TĀIKO EDUCATIONAL RESOURCE Student learning sheets Treasures of the Hauraki Gulf Marine Park Sea bird bingo Recording knowledge Sea birds of the Hauraki Gulf Inquiry cycle Adaptations of tāiko Wonders of the Gulf: Seabirds return Lifecycle descriptions Lifecycle of the Tāiko Red-billed gull facts Little blue penguin/korora facts Gannet facts Black petrel/taiko facts Groups of people and seabirds Student inquiry notes Brief Seabirds: what is the same/different? Action Plan BLACK PETREL / TĀIKO EDUCATIONAL RESOURCE INTRODUCTION About this resource This resource is an integrated unit of teaching and learning material about the black petrel/ tāiko and other seabirds, for use in primary schools. Students are first introduced to seabirds and the black petrel/ tāiko and then extend their learning inquiry to investigate and research gannets/tākapu, little blue penguins/kororā and red-billed gulls/tarāpunga. They go on to look at various aspects of a focus seabird and examine the issues affecting it. The unit concludes with planning and implementing informed, meaningful action for seabirds. The resource has been developed for year 5 - 8 primary teachers, with a New Zealand context. -

Black Petrels on Hauturu-Little Barrier Island 2015-16 Season

Black petrel (Procellaria parkinsoni) population study on Hauturu‐o‐Toi/Little Barrier Island, 2015/16 Black petrels (Procellaria parkinsoni) population study on Hauturu‐o‐Toi/Little Barrier Island, 2015/16. Elizabeth A. Bell1, Claudia P. Mischler2, Nikki MacArthur3 and Joanna L. Sim4 1. Corresponding author: Wildlife Management International Limited, PO Box 607, Blenheim 7240, New Zealand, Email: [email protected] 2. Wildlife Management International Limited, PO Box 607, Blenheim 7240, New Zealand 3. Wildlife Management International Limited, PO Box 607, Blenheim 7240, New Zealand 4. DabChickNZ, Levin, New Zealand This report was prepared by Wildlife Management International Limited for the Department of Conservation as fulfilment of the contract 4652‐2 (Black petrel population study at Little Barrier Island) dated 21 December 2015. 15 September 2016 Citation: This report should be cited as: Bell, E.A.; Mischler, C.P.; MacArthur, N.; Sim, J.L. 2016. Black petrel (Procellaria parkinsoni) population study on Hauturu‐o‐Toi/Little Barrier Island, 2015/16. Report to the Conservation Services Programme, Department of Conservation. Wellington, New Zealand. All photographs in this Report are copyright © WMIL unless otherwise credited, in which case the person or organization credited is the copyright holder. Frontispiece: Niki MacArthur (WMIL, banding a black petrel chick with Adam Clow and Ashe Pollock (Whitianga fishers) assisting, May 2016. Bell et al. 2016: Black petrels on Little Barrier Island (POP2015/01) ABSTRACT This report covers the population monitoring of black petrels, Procellaria parkinsoni, on Hauturu‐o‐Toi/Little Barrier Island in the 2015/16 breeding season. On Hauturu‐o‐Toi/Little Barrier Island, 149 study burrows were monitored, of which 92 were original study burrows established in 1997 by Mike Imber. -

Humboldt Current and the Juan Fernández Archipelago November 2014

Expedition Research Report Humboldt Current and the Juan Fernández archipelago November 2014 Expedition Team Robert L. Flood, Angus C. Wilson, Kirk Zufelt Mike Danzenbaker, John Ryan & John Shemilt Juan Fernández Petrel KZ Stejneger’s Petrel AW First published August 2017 by www.scillypelagics.com © text: the authors © video clips: the copyright in the video clips shall remain with each individual videographer © photographs: the copyright in the photographs shall remain with each individual photographer, named in the caption of each photograph All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form or by any means – graphic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping or information storage and retrieval systems – without the prior permission in writing of the publishers. 2 CONTENTS Report Summary 4 Introduction 4 Itinerary and Conditions 5 Bird Species Accounts 6 Summary 6 Humboldt Current and Coquimbo Bay 7 Passages Humboldt Current to Juan Fernández and return 13 At sea off the Juan Fernández archipelago 18 Ashore on Robinson Crusoe Island 26 Cetaceans and Pinnipeds 28 Acknowledgements 29 References 29 Appendix: Alpha Codes 30 White-bellied Storm-petrel JR 3 REPORT SUMMARY This report summarises our observations of seabirds seen during an expedition from Chile to the Juan Fernández archipelago and return, with six days in the Humboldt Current. Observations are summarised by marine habitat – Humboldt Current, oceanic passages between the Humboldt Current and the Juan Fernández archipelago, and waters around the Juan Fernández archipelago. Also summarised are land bird observations in the Juan Fernández archipelago, and cetaceans and pinnipeds seen during the expedition. Points of interest are briefly discussed. -

Analysis of Albatross and Petrel Distribution Within the CCAMLR Convention Area: Results from the Global Procellariiform Tracking Database

CCAMLR Science, Vol. 13 (2006): 143–174 ANALYSIS OF ALBATROSS AND PETREL DISTRIBUTION WITHIN THE CCAMLR CONVENTION AREA: RESULTS FROM THE GLOBAL PROCELLARIIFORM TRACKING DATABASE BirdLife International (prepared by C. Small and F. Taylor) Wellbrook Court, Girton Road Cambridge CB3 0NA United Kingdom Correspondence address: BirdLife Global Seabird Programme c/o Royal Society for the Protection of Birds The Lodge, Sandy Bedfordshire SG19 2DL United Kingdom Email – [email protected] Abstract CCAMLR has implemented successful measures to reduce the incidental mortality of seabirds in most of the fisheries within its jurisdiction, and has done so through area- specific risk assessments linked to mandatory use of measures to reduce or eliminate incidental mortality, as well as through measures aimed at reducing illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing. This paper presents an analysis of the distribution of albatrosses and petrels in the CCAMLR Convention Area to inform the CCAMLR risk- assessment process. Albatross and petrel distribution is analysed in terms of its division into FAO areas, subareas, divisions and subdivisions, based on remote-tracking data contributed to the Global Procellariiform Tracking Database by multiple data holders. The results highlight the importance of the Convention Area, particularly for breeding populations of wandering, grey-headed, light-mantled, black-browed and sooty albatross, and populations of northern and southern giant petrel, white-chinned petrel and short- tailed shearwater. Overall, the subareas with the highest proportion of albatross and petrel breeding distribution were Subareas 48.3 and 58.6, adjacent to the southwest Atlantic Ocean and southwest Indian Ocean, but albatross and petrel breeding ranges extend across the majority of the Convention Area. -

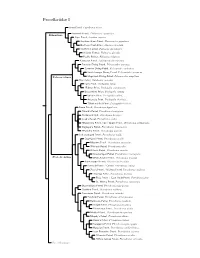

Procellariidae Species Tree

Procellariidae I Snow Petrel, Pagodroma nivea Antarctic Petrel, Thalassoica antarctica Fulmarinae Cape Petrel, Daption capense Southern Giant-Petrel, Macronectes giganteus Northern Giant-Petrel, Macronectes halli Southern Fulmar, Fulmarus glacialoides Atlantic Fulmar, Fulmarus glacialis Pacific Fulmar, Fulmarus rodgersii Kerguelen Petrel, Aphrodroma brevirostris Peruvian Diving-Petrel, Pelecanoides garnotii Common Diving-Petrel, Pelecanoides urinatrix South Georgia Diving-Petrel, Pelecanoides georgicus Pelecanoidinae Magellanic Diving-Petrel, Pelecanoides magellani Blue Petrel, Halobaena caerulea Fairy Prion, Pachyptila turtur ?Fulmar Prion, Pachyptila crassirostris Broad-billed Prion, Pachyptila vittata Salvin’s Prion, Pachyptila salvini Antarctic Prion, Pachyptila desolata ?Slender-billed Prion, Pachyptila belcheri Bonin Petrel, Pterodroma hypoleuca ?Gould’s Petrel, Pterodroma leucoptera ?Collared Petrel, Pterodroma brevipes Cook’s Petrel, Pterodroma cookii ?Masatierra Petrel / De Filippi’s Petrel, Pterodroma defilippiana Stejneger’s Petrel, Pterodroma longirostris ?Pycroft’s Petrel, Pterodroma pycrofti Soft-plumaged Petrel, Pterodroma mollis Gray-faced Petrel, Pterodroma gouldi Magenta Petrel, Pterodroma magentae ?Phoenix Petrel, Pterodroma alba Atlantic Petrel, Pterodroma incerta Great-winged Petrel, Pterodroma macroptera Pterodrominae White-headed Petrel, Pterodroma lessonii Black-capped Petrel, Pterodroma hasitata Bermuda Petrel / Cahow, Pterodroma cahow Zino’s Petrel / Madeira Petrel, Pterodroma madeira Desertas Petrel, Pterodroma -

Investigating Spatiotemporal Variation in the Diet of Westland Petrel Through

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.10.30.360289; this version posted August 17, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC 4.0 International license. 1 Investigating spatiotemporal variation in the diet of Westland Petrel through 2 metabarcoding, a non-invasive technique 3 Marina Querejeta1, Marie-Caroline Lefort2,3, Vincent Bretagnolle4, Stéphane Boyer1,2 4 5 6 1 Institut de Recherche sur la Biologie de l'Insecte, UMR 7261, CNRS-Université de Tours, 7 Tours, France 8 2 Environmental and Animal Sciences, Unitec Institute of Technology, 139 Carrington Road, 9 Mt Albert, Auckland 1025, New Zealand 10 3 Cellule de Valorisation Pédagogique, Université de Tours, 60 rue du Plat d’Étain, 37000 11 Tours, France. 12 4 Centre d’Études Biologiques de Chizé, UMR 7372, CNRS & La Rochelle Université, 79360 13 Villiers en Bois, France. 14 15 16 17 18 19 Running head: Spatiotemporal variation in diet of Westland Petrel 20 21 Keywords: Conservation, metabarcoding, dietary DNA, biodiversity, New Zealand, 22 Procellaria westlandica 23 24 Abstract 25 As top predators, seabirds are in one way or another impacted by any changes in marine 26 communities, whether they are linked to climate change or caused by commercial fishing 27 activities. However, their high mobility and foraging behaviour enables them to exploit prey 28 distributed patchily in time and space. This capacity of adaptation comes to light through 29 the study of their diet.