Doukhobor-Sinixt Relations at the Confluence of the Kootenay and Columbia Rivers in the Early Twentieth Century

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Columbia River Treaty: Recommendations December 2013

L O CA L GOVERNMEN TS’ COMMI TTEE Columbia River Treaty: Recommendations December 2013 The BC Columbia River Treaty Local Governments’ Committee (the Committee) has prepared these Recommendations in response to the Columbia River Treaty-related interests and issues raised by Columbia River Basin residents in Canada. These Recommendations are based on currently-available information. They have been submitted to the provincial and federal governments for incorporation into current decisions regarding the future of the Columbia River Treaty (CRT). The Committee plans to monitor the BC, Canadian and U.S. CRT-related processes and be directly involved when appropriate. As new information becomes available, the Committee will review this information, seek input from Basin residents, and submit further recommendations to the provincial and federal governments, if needed. The CRT Local Governments’ Committee will post its recommendations and other documents at www.akblg.ca/content/columbia-river-treaty. For more information contact the Committee Chair, Deb Kozak ([email protected] 250 352-9383) or the Executive Director, Cindy Pearce ([email protected] 250 837-3966). Background Beginning in 2024, either the U.S. or Canada can The Columbia River Treaty (Treaty) was ratified terminate substantial portions of the Treaty, by Canada and the United States (the U.S.) in with at least 10 years’ prior notice. Canada—via 1964, resulting in the construction of three the BC Provincial Government—and the U.S. are dams in Canada—Mica Dam north of both conducting reviews to consider whether to Revelstoke; Hugh Keenleyside Dam near continue, amend or terminate the Treaty. Castlegar; and Duncan Dam north of Kaslo—and Local governments within the Basin have Libby Dam near Libby, Montana. -

Francophone Historical Context Framework PDF

Francophone Historic Places Historical Context Thematic Framework Canot du nord on the Fraser River. (www.dchp.ca); Fort Victoria c.1860. (City of Victoria); Fort St. James National Historic Site. (pc.gc.ca); Troupe de danse traditionnelle Les Cornouillers. (www. ffcb.ca) September 2019 Francophone Historic Places Historical Context Thematic Framework Francophone Historic Places Historical Context Thematic Framework Table of Contents Historical Context Thematic Framework . 3 Theme 1: Early Francophone Presence in British Columbia 7 Theme 2: Francophone Communities in B.C. 14 Theme 3: Contributing to B.C.’s Economy . 21 Theme 4: Francophones and Governance in B.C. 29 Theme 5: Francophone History, Language and Community 36 Theme 6: Embracing Francophone Culture . 43 In Closing . 49 Sources . 50 2 Francophone Historic Places Historical Context Thematic Framework - cb.com) - Simon Fraser et ses Voya ses et Fraser Simon (tourisme geurs. Historical contexts: Francophone Historic Places • Identify and explain the major themes, factors and processes Historical Context Thematic Framework that have influenced the history of an area, community or Introduction culture British Columbia is home to the fourth largest Francophone community • Provide a framework to in Canada, with approximately 70,000 Francophones with French as investigate and identify historic their first language. This includes places of origin such as France, places Québec, many African countries, Belgium, Switzerland, and many others, along with 300,000 Francophiles for whom French is not their 1 first language. The Francophone community of B.C. is culturally diverse and is more or less evenly spread across the province. Both Francophone and French immersion school programs are extremely popular, yet another indicator of the vitality of the language and culture on the Canadian 2 West Coast. -

HONS),University of Ghana, Legon, 1997

WELCOME STRANGER: TOüRiSbl DEVELOPhdENT AMONG THE SI fUSWAP PEOPLE OF THE SOUTH-CENTRAL INTERTOR OF BRITISH COLUMBIA, CAVADA Owusu A. Amoakohene B.A. (HONS),University of Ghana, Legon, 1997. THESIS SUBMTTED lN PARTIAL FULFILLLMENTOF THE REQUIREiLLENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in The Department of Sociology and Anthropology OOwusu A. Amoakohene 1997 SIMON FRASER WRSITY Juiy 1997 Al1 rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced in whoIe or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. National Library Bibliothèque nationale 1*1 of Canada du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographie Services seMces bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395, nie Wellington OttawaON K1A ON4 OttawaON K1A ON4 Canada Canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant A la National Library of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, Ioan, distri'bute or seU reproduire, prêter, distriiuer ou copies of this thesis in microfonn, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la fome de microfiche/fh, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts fi-om it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. ABSTRACT TouRsm development has become an important source of economic and socio- cuItural developrnent for many cornrnunities. -

2018 Statement of Financial Information

2018 Statement of Financial Information Columbia Shuswap Regional District - May 2017 1 Columbia Shuswap Regional District Statement of Financial Information Approval The undersigned represents the Board of Directors of the Columbia Shuswap Regional District and approves all the statements and schedules included in this Statement of Financial Information, produced under the Financial Information Act. ^Vvov^_. Rhona Martin Chair, Columbia Shuswap Regional District Date: ra i^,7^i^ Prepared under the Financial Information Regulation, Schedule 1, subsection 9(2) Columbia Shuswap Regional District Management Report The Financial Statements contained in this Statement of Financial Information under the Financial Information Act have been prepared by management in accordance with generally accepted accounting principles for British Columbia Regional Districts, and the integrity and objectivity of these statements are management's responsibility. Management is also responsible for all the statements and schedules, and for ensuring that this information is consistent, where appropriate, with the information contained in the financial statements. Management is also responsible for implementing and maintaining a system of internal controls to provide reasonable assurance that reliable financial information is produced. The Board of Directors is responsible for ensuring that management fulfils its responsibilities for financial reporting and internal control, including reviewing and approving the financial statements. The external auditors, BDO Canada LLP, conduct an independent examination, in accordance with generally accepted auditing standards, and express their opinion on the financial statements. Their examination does not relate to the other schedules and statements required by the Act. Their examination includes a review and evaluation of the regional district's system of internal control and appropriate tests and procedures to provide reasonable assurance that the financial statements are presented fairly. -

Kootenai River Resident Fish Mitigation: White Sturgeon, Burbot, Native Salmonid Monitoring and Evaluation

KOOTENAI RIVER RESIDENT FISH MITIGATION: WHITE STURGEON, BURBOT, NATIVE SALMONID MONITORING AND EVALUATION Annual Progress Report May 1, 2016 — April 31, 2017 BPA Project # 1988-065-00 Report covers work performed under BPA contract # 68393 IDFG Report Number 08-09 April 2018 This report was funded by the Bonneville Power Administration (BPA), U.S. Department of Energy, as part of BPA's program to protect, mitigate, and enhance fish and wildlife affected by the development and operation of hydroelectric facilities on the Columbia River and its tributaries. The views in this report are the author's and do not necessarily represent the views of BPA. This report should be cited as follows: Ross et al. 2018. Report for 05/01/2016 – 04/30/2017. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page CHAPTER 1: KOOTENAI STURGEON MONITORING AND EVALUATION ............................... 1 ABSTRACT ................................................................................................................................. 1 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................2 OBJECTIVE ................................................................................................................................3 STUDY SITE ...............................................................................................................................3 METHODS ..................................................................................................................................3 Water -

Keeping the Lakes' Way": Reburial and the Re-Creation of a Moral World Among an Invisible People Paula Pryce Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1999

I02 BC STUDIES "Keeping the Lakes' Way": Reburial and the Re-creation of a Moral World among an Invisible People Paula Pryce Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1999. 203 pp. Illus., maps. $17.95 paper. By Randy Bouchard and Dorothy Kennedy British Columbia Indian Language Project, Victoria HE SINIXT (sngaytskstx), or in 1985. Although these chapters rely Lakes people, an Aboriginal heavily upon the facts documented in T group of the Arrow Lakes our reports, Pryce nevertheless deviates region, were deemed "extinct" by the from our analysis of Sinixt history federal and provincial governments when she hypothesizes that the iso almost fifty years ago. This remains an lated Slocan and Arrow Lakes pro unresolved chapter in the history of vided a refuge where the Sinixt could British Columbia's First Nations. Like live in peace in the mid-nineteenth the author of this volume, we became century, away from the Plateau Indian intrigued by the question of why there wars of the 1850s, and that they had a are no Sinixt Indian reserves in British "latent presence" north of the border Columbia. The issue first came to our until near the twentieth century. attention when a Sinixt elder from Pryce's thesis (8) is complete con the Colville Indian Reservation in jecture. She does not present a single Washington State walked into our piece of evidence to support it. office in 1972 seeking information If Pryce's argument retains any about his people's history in British plausibility, then it is only because Columbia. Our personal voyage of there is very little documentation discovery, which led us to dozens of pertaining to this area between the archives throughout Canada and the 1840s and 1850s that could either prove United States, resulted in a lengthy or disprove her thesis. -

Ethnohistory of the Kootenai Indians

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1983 Ethnohistory of the Kootenai Indians Cynthia J. Manning The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Manning, Cynthia J., "Ethnohistory of the Kootenai Indians" (1983). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 5855. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/5855 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COPYRIGHT ACT OF 1976 Th is is an unpublished m a n u s c r ip t in w h ic h c o p y r ig h t su b s i s t s . Any further r e p r in t in g of it s c o n ten ts must be a ppro ved BY THE AUTHOR. MANSFIELD L ib r a r y Un iv e r s it y of Montana D a te : 1 9 8 3 AN ETHNOHISTORY OF THE KOOTENAI INDIANS By Cynthia J. Manning B.A., University of Pittsburgh, 1978 Presented in partial fu lfillm en t of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts UNIVERSITY OF MONTANA 1983 Approved by: Chair, Board of Examiners Fan, Graduate Sch __________^ ^ c Z 3 ^ ^ 3 Date UMI Number: EP36656 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. -

Indigenous Peoples' Rights Image Attributions

Indigenous Peoples’ Rights Image Attributions. The following list contains image and document attributions for the assets used in the lecture videos of Columbia University’s Massive Open Online Course (MOOC), Indigenous Peoples Rights. The attributions are listed in order of appearance. We hope that this document serves as a useful resource for your own research or interests. Table of Contents. Module 1. The Indigenous Peoples’ Rights Movement. Module 2. Right to Self-Determination. Module 3. Right to Land, Territories, and Resources. Module 4. Cultural Rights. Module 5. UN Indigenous Peoples-Related Mechanisms: The Power of Advocacy. Course Timeline. Module 1: The Indigenous Peoples’ Rights Movement. Video: Origins of the Movement,. Christoph Hensch. “Homelands a Human Right.” B&W photo of a protest for Indigenous Peoples. May 1, 2015. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0. https://flic.kr/p/tb7thg. Santiago Sito. “Marcha a favor de Evo Morales - Buenos Aires.” Boy holds a flag, marching in favor of Bolivian president/indigenous leader Evo Morales. November, 18, 2019. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0. https://flic.kr/p/2hNH1n1. Protect the Inlet. “April 7, 2018, Burnaby Mountain, BC, Canada.” Grand Chief Stewart Phillip addresses the crowd. April 7, 2018. Public Domain. https://flic.kr/p/GgDwbe. 1 Broddi Sigurdarson. “confroom2.” Extreme wide shot of UN Permanent Forum on Indigneous Issues UNPFII. Circa 2000s. All rights reserved by the owner. Permission granted for this project. United Nations, Rick Bajornas. “Even Marking International Day of the Indigenous Peoples.” Two Indigenous women at the UN with earpieces and an Indigenous Peoples sign. August 24, 2016. -

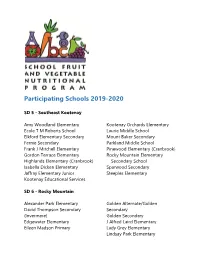

Participating Schools 2019-2020

Participating Schools 2019-2020 SD 5 - Southeast Kootenay Amy Woodland Elementary Kootenay Orchards Elementary Ecole T M Roberts School Laurie Middle School Elkford Elementary Secondary Mount Baker Secondary Fernie Secondary Parkland Middle School Frank J Mitchell Elementary Pinewood Elementary (Cranbrook) Gordon Terrace Elementary Rocky Mountain Elementary Highlands Elementary (Cranbrook) Secondary School Isabella Dicken Elementary Sparwood Secondary Jaffray Elementary Junior Steeples Elementary Kootenay Educational Services SD 6 - Rocky Mountain Alexander Park Elementary Golden Alternate/Golden David Thompson Secondary Secondary (Invermere) Golden Secondary Edgewater Elementary J Alfred Laird Elementary Eileen Madson Primary Lady Grey Elementary Lindsay Park Elementary Martin Morigeau Elementary Open Doors Alternate Education Marysville Elementary Selkirk Secondary McKim Middle School Windermere Elementary Nicholson Elementary SD 8 - Kootenay Lake Adam Robertson Elementary Mount Sentinel Secondary Blewett Elementary School Prince Charles Brent Kennedy Elementary Secondary/Wildflower Program Canyon-Lister Elementary Redfish Elementary School Crawford Bay Elem-Secondary Rosemont Elementary Creston Homelinks/Strong Start Salmo Elementary Erickson Elementary Salmo Secondary Hume Elementary School South Nelson Elementary J V Humphries Trafalgar Middle School Elementary/Secondary W E Graham Community School Jewett Elementary Wildflower School L V Rogers Secondary Winlaw Elementary School SD 10 - Arrow Lakes Burton Elementary School Edgewood -

Outline of United States Federal Indian Law and Policy

Outline of United States federal Indian law and policy The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to United States federal Indian law and policy: Federal Indian policy – establishes the relationship between the United States Government and the Indian Tribes within its borders. The Constitution gives the federal government primary responsibility for dealing with tribes. Law and U.S. public policy related to Native Americans have evolved continuously since the founding of the United States. David R. Wrone argues that the failure of the treaty system was because of the inability of an individualistic, democratic society to recognize group rights or the value of an organic, corporatist culture represented by the tribes.[1] U.S. Supreme Court cases List of United States Supreme Court cases involving Indian tribes Citizenship Adoption Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians v. Holyfield, 490 U.S. 30 (1989) Adoptive Couple v. Baby Girl, 530 U.S. _ (2013) Tribal Ex parte Joins, 191 U.S. 93 (1903) Santa Clara Pueblo v. Martinez, 436 U.S. 49 (1978) Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians v. Holyfield, 490 U.S. 30 (1989) South Dakota v. Bourland, 508 U.S. 679 (1993) Civil rights Oliphant v. Suquamish Indian Tribe, 435 U.S. 191 (1978) United States v. Wheeler, 435 U.S. 313 (1978) Congressional authority Ex parte Joins, 191 U.S. 93 (1903) White Mountain Apache Tribe v. Bracker, 448 U.S. 136 (1980) California v. Cabazon Band of Mission Indians, 480 U.S. 202 (1987) South Dakota v. Bourland, 508 U.S. 679 (1993) United States v. -

February 10, 2010 the Valley Voice 1

February 10, 2010 The Valley Voice 1 Volume 19, Number 3 February 10, 2010 Delivered to every home between Edgewood, Kaslo & South Slocan. Published bi-weekly. “Your independently owned regional community newspaper serving the Arrow Lakes, Slocan & North Kootenay Lake Valleys.” WE Graham and Winlaw Schools under review for closure or re-configuration by Jan McMurray The estimated savings of closing move the VWP to Mt. Sentinel. near Castlegar that was closed, but kindergarteners, and said she hoped School District No. 8’s board Winlaw School is $64,000. In this Campbell answered, “Anything is the funding was still coming in and parents would ask board members to of education will decide the fate of scenario, it was assumed that all possible.” there were still community programs consider this in their decision. Winlaw and WE Graham Schools kids from the two communities Another concern if WEG running at the school. Ahead of the February 16 on April 13, as part of the district’s would go to WEG, although it was closes is the fate of WE Graham Former Slocan Valley school meeting at WEG, parents are asked ongoing review of its facilities. acknowledged that some parents Community Service Society. The trustee, Penny Tees, commented to submit their ideas in writing to the At a public meeting in Winlaw would choose to send their children society gets some of its funding from that busing was at the core of the district office in Nelson, or to book on February 1, the board and some south to Brent Kennedy. The 7/8 the school district because WEG has three options. -

CRSRI Bringing the Salmon Home 2020-21 Annual Report

OUR LOGO STORY An artist from each Nation contributed an original salmon design to the unified logo for Bringing the Salmon Home: The Columbia River Salmon Reintroduction Initiative. Our logo was launched with our new website at ColumbiaRiverSalmon.ca on February 16, 2021. DARCY LUKE, KTUNAXA NATION Darcy Luke is a Ktunaxa artist versatile in different mediums. Darcy created a chinook salmon whose design symbolizes the life-giving generational legacy of the salmon. KELSEY JULES, SECWÉPEMC NATION Kelsey Jules is a Secwépemc and Syilx artist, model, and teacher. She is a member of Tk'emlups te Secwepemc. Kelsey’s sockeye salmon design embodies the vital relationship between salmon, land and water. TUNKA CIKALA, SYILX OKANAGAN NATION Tunka Cikala (Spirit Peoples) is a member of the Sinixt and Nespelem bands of the Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation. Spirit’s chinook salmon design is inspired by Syilx captíkwł teachings, illustrating the inseparable connections between salmon and culture. Here, Sen’k’lip (Coyote) with his Eagle staff brings salmon up the river to the people. Bear paw prints represent Skəmixst as well as the spots on the back of chinook salmon. The Syilx Okanagan captíkwł How Food Was Given relates how the Four Food Chiefs – Chief Skəmixst (Black Bear), Chief N’titxw (Chinook Salmon), Chief Spʼiƛ̕əm (Bitter Root), and Chief Siyaʔ (Saskatoon Berry), met the needs of the “People To Be”. 2 YEAR TWO OF OUR JOURNEY Five governments, one visionary agreement Bringing the Salmon Home: The Columbia River Salmon Reintroduction Initiative is the Indigenous-led collaboration of the Syilx Okanagan Nation, Ktunaxa Nation, Secwépemc Nation, Canada and British Columbia.