Bud Microclimate and Fruitfulness in Vitis Vinifera L

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Xylella Fastidiosa HOST: GRAPEVINE

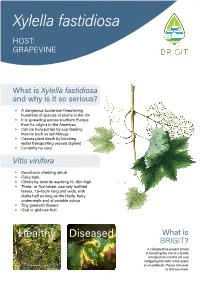

Xylella fastidiosa HOST: GRAPEVINE What is Xylella fastidiosa and why is it so serious? ◆ A dangerous bacterium threatening hundreds of species of plants in the UK ◆ It is spreading across southern Europe from its origins in the Americas ◆ Can be transported by sap-feeding insects such as spittlebugs ◆ Causes plant death by blocking water transporting vessels (xylem) ◆ Currently no cure Vitis vinifera ◆ Deciduous climbing shrub ◆ Flaky bark ◆ Climbs by tendrils reaching 15–18m high ◆ Three- or five-lobed, coarsely toothed leaves, 7.5–15cm long and wide, with stalks half as long as the blade, hairy underneath and of variable colour ◆ Tiny greenish flowers ◆ Oval or globose fruit Healthy Diseased What is BRIGIT? A collaborative project aimed at reducing the risk of a Xylella introduction into the UK and mitigating the risks in the event of an outbreak. Please turn over to find out more. What to look 1 out for 2 ◆ Marginal leaf scorch 1 ◆ Leaf chlorosis 2 ◆ Premature loss of leaves 3 ◆ Matchstick petioles 3 ◆ Irregular cane maturation (green islands in stems) 4 ◆ Fruit drying and wilting 5 ◆ Stunting of new shoots 5 ◆ Death of plant in 1–5 years Where is the plant from? 3 ◆ Plants sourced from infected countries are at a much higher risk of carrying the disease-causing bacterium Do not panic! 4 How long There are other reasons for disease symptoms to appear. Consider California. of University Montpellier; watercolour, RHS Lindley Collections; “healthy”, RHS / Tim Sandall; “diseased”, J. Clark, California 3 J. Clark & A.H. Purcell, University of California 4 J. Clark, University of California 5 ENSA, Images © 1 M. -

View the PDF: 10F-Ideas-Z2-Design-Facility-San

C A S E S T U D Y D I e A s Z 2 DESIGN FACILITY t the first conceptual The team needed a fully integrated BUILDING AT A GLANCE design charrette, the design process, in which the differ- design team decided to ent design disciplines and the gen- Name IDeAs Z2 Design Facility 2 target a “Z ” goal — eral contractor make key decisions Location San Jose, Calif. Azero energy and zero carbon — to together to optimize the building as Owner Integrated Design Associates advance the state of green build- an integrated system. For example, (IDeAs) ing and to showcase the low energy carefully designed sun shading and When Built mid-1960s (originally a electrical and lighting design skills state-of-the-art glazing would allow bank branch office) of the client. For the project to be the team to make many incisions Major Renovation 2007 Renovation Scope Skylights, window replicable, the team wanted a low into the roof and concrete walls to walls, upgraded insulation and energy building that uses exist- harvest more daylight. This would glazing, high-efficiency HVAC system, high-efficiency lighting and office equip- ing technology at a reasonable cost reduce the need for electric lighting ment, rooftop and canopy photovoltaic premium. By maximizing efficiency and its attendant energy consump- system, monitoring equipment of building systems before sizing tion, while also providing outside Principal Use Commercial office the photovoltaic arrays to cover the views for building occupants. Occupants 15 remaining loads, the costs were kept Team members collaborated on Gross Square Footage 7,000 to a minimum. -

So You Want to Grow Grapes in Tennessee

Agricultural Extension Service The University of Tennessee PB 1689 So You Want to Grow Grapes in Tennessee 1 conditions. American grapes are So You Want to Grow versatile. They may be used for fresh consumption (table grapes) or processed into wine, juice, jellies or Grapes in Tennessee some baked products. Seedless David W. Lockwood, Professor grapes are used mostly for fresh Plant Sciences and Landscape Systems consumption, with very little demand for them in wines. Yields of seedless varieties do not match ennessee has a long history of grape production. Most recently, those of seeded varieties. They are T passage of the Farm Winery Act in 1978 stimuated an upsurge of also more susceptible to certain interest in grape production. If you are considering growing grapes, the diseases than the seeded American following information may be useful to you. varieties. French-American hybrids are crosses between American bunch 1. Have you ever grown winery, the time you spend visiting and V. vinifera grapes. Their grapes before? others will be a good investment. primary use is for wine. uccessful grape production Vitis vinifera varieties are used S requires a substantial commit- 3. What to grow for wine. Winter injury and disease ment of time and money. It is a American problems seriously curtail their marriage of science and art, with a - seeded growth in Tennessee. good bit of labor thrown in. While - seedless Muscadines are used for fresh our knowledge of how to grow a French-American hybrid consumption, wine, juice and jelly. crop of grapes continues to expand, Vitis vinifera Vines and fruits are not very we always need to remember that muscadine susceptible to most insects and some crucial factors over which we Of the five main types of grapes diseases. -

Multi-Scale Analysis of the Surface Layer Urban Heat Island Effect in Five Higher Density Precincts of Central Sydney

Sharifi, E., Philipp, C., & Lehmann, S. (2015). Multi-scale analysis of the surface layer urban heat island effect in five higher density precincts of central Sydney. In S. Lehmann (Ed.), Low Carbon Cities (pp. 375-393). New York: Routledge. Chapter 21 Multi-scale analysis of the surface layer urban heat island effect in five higher density precincts of central Sydney Ehsan Sharifi, Conrad Philipp and Steffen Lehmann Summary The urban heat island (UHI) effect is invariably present in cities, mainly due to increased urbanisation. It can result in higher urban densities being significantly hotter (frequently more than 4°C, even up to 10°C) than their peri-urban surroundings. Urban structure and land cover are key contributors to the surface layer urban heat island (sUHI) effect at city and district scale. This research aims to explore which urban configurations can make urban precincts and their microclimates more resilient to the dangerous sUHI effect. In the context of the city of Sydney, Australia, the research aims to explore the most heat resilient urban features for neighbourhoods, at precinct scale. The investigation examines five high density precincts in central Sydney. The analysis of these precincts is based on remote sensing thermal data of two independent sources: a nocturnal remote-sensing thermal image of central Sydney on 6 February 2009 and a diurnal Landsat 7– ETM+ data from 2008-2009. Comparing the surface temperature of streetscape and buildings’ rooftop feature layers indicates that open spaces are the urban elements most sensitive to the sUHI effect. Therefore, the correlations between street network intensity, open public space ratio, and urban greenery plot ratio and sUHI effect are being analysed in the five high density precincts selected. -

Canopy Microclimate Modification for the Cultivar Shiraz II. Effects on Must and Wine Composition

Vitis 24, 119-128 (1985) Roseworthy Agricultural College, Roseworth y, South Australia South Australian Department of Agriculture, Adelaide, South Austraha Canopy microclimate modification for the cultivar Shiraz II. Effects on must and wine composition by R. E. SMART!), J. B. ROBINSON, G. R. DUE and c. J. BRIEN Veränderungen des Mikroklimas der Laubwand bei der Rebsorte Shiraz II. Beeinflussung der Most- und Weinzusammensetzung Z u sam menfa ss u n g : Bei der Rebsorte Shiraz wurde das Ausmaß der Beschattung innerha lb der Laubwand künstlich durch vier Behandlungsformen sowie natürlicherweise durch e ine n Wachstumsgradienten variiert. Beschattung bewirkte in den Traubenmosten eine Erniedri gung de r Zuckergehalte und eine Erhöhung der Malat- und K-Konzentrationen sowie der pH-Werte. Die Weine dieser Moste wiesen ebenfalls höhere pH- und K-Werte sowie einen venin gerten Anteil ionisierter Anthocyane auf. Statistische Berechnungen ergaben positive Korrelatio nen zwischen hohen pH- und K-Werten in Most und Wein einerseits u11d der Beschattung der Laubwand andererseits; die Farbintensität sowie die Konzentrationen der gesamten und ionisier ten Anthocyane und der Phenole waren mit der Beschattung negativ korreliert. Zur Beschreibung der Lichtverhältnisse in der Laubwand wurde ei11 Bonitierungsschema, das sich auf acht Merkmale stützt, verwendet; die hiermit gewonne nen Ergebnisse korrelierten mit Zucker, pH- und K-Werten des Mostes sowie mit pH, Säure, K, Farbintensität, gesamten und ionj sierten Anthocyanen und Phenolen des Weines. Starkwüchsige Reben lieferten ähnliche Werte der Most- und Weinzusammensetzung wie solche mit künstlicher Beschattung. K e y wo r d s : climate, light, growth, must quality, wine quality, malic acid, potassium, aci dity, anthocyanjn. -

Kentucky Viticultural Regions and Suggested Cultivars S

HO-88 Kentucky Viticultural Regions and Suggested Cultivars S. Kaan Kurtural and Patsy E. Wilson, Department of Horticulture, University of Kentucky; Imed E. Dami, Department of Horticulture and Crop Science, The Ohio State University rapes grown in Kentucky are sub- usually more harmful to grapevines than Even in established fruit growing areas, ject to environmental stresses that steady cool temperatures. temperatures occasionally reach critical reduceG crop yield and quality, and injure Mesoclimate is the climate of the vine- levels and cause significant damage. The and kill grapevines. Damaging critical yard site affected by its local topography. moderate hardiness of grapes increases winter temperatures, late spring frosts, The topography of a given site, including the likelihood for damage since they are short growing seasons, and extreme the absolute elevation, slope, aspect, and the most cold-sensitive of the temperate summer temperatures all occur with soils, will greatly affect the suitability of fruit crops. regularity in regions of Kentucky. How- a proposed site. Mesoclimate is much Freezing injury, or winterkill, oc- ever, despite the challenging climate, smaller in area than macroclimate. curs as a result of permanent parts of certain species and cultivars of grapes Microclimate is the environment the grapevine being damaged by sub- are grown commercially in Kentucky. within and around the canopy of the freezing temperatures. This is different The aim of this bulletin is to describe the grapevine. It is described by the sunlight from spring freeze damage that kills macroclimatic features affecting grape exposure, air temperature, wind speed, emerged shoots and flower buds. Thus, production that should be evaluated in and wetness of leaves and clusters. -

Environmental Study

Initial Environmental Review: 9000 Block Highway 99, BC Prepared by: Cascade Environmental Resource Group Ltd. Unit 3 – 1005 Alpha Lake Road Whistler, BC V0N 1B1 Prepared for: 28165 Yukon Inc. 5403 Buckingham Avenue Burnaby, BC, V5E 1Z9 Project No.: 089-05-18 Date: August 1, 2019 Table of Contents Statement of Limitations ............................................................................................................................ 1 1 Introduction .......................................................................................................................................... 2 1.1 Scope .............................................................................................................................................. 2 1.2 The Project Team ........................................................................................................................... 2 1.3 Location .......................................................................................................................................... 2 1.4 SLRD Bylaw Zoning........................................................................................................................ 2 1.5 Methodology ................................................................................................................................... 3 2 Existing Environmental Conditions ................................................................................................. 11 2.1 Historical and Existing Land Use ................................................................................................. -

Dual RNA Sequencing of Vitis Vinifera During Lasiodiplodia Theobromae Infection Unveils Host–Pathogen Interactions

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Article Dual RNA Sequencing of Vitis vinifera during Lasiodiplodia theobromae Infection Unveils Host–Pathogen Interactions Micael F. M. Gonçalves 1 , Rui B. Nunes 1, Laurentijn Tilleman 2 , Yves Van de Peer 3,4,5 , Dieter Deforce 2, Filip Van Nieuwerburgh 2, Ana C. Esteves 6 and Artur Alves 1,* 1 Department of Biology, CESAM, University of Aveiro, 3810-193 Aveiro, Portugal; [email protected] (M.F.M.G.); [email protected] (R.B.N.) 2 Laboratory of Pharmaceutical Biotechnology, Campus Heymans, Ottergemsesteenweg 460, B-9000 Ghent, Belgium; [email protected] (L.T.); [email protected] (D.D.); [email protected] (F.V.N.) 3 Department of Plant Biotechnology and Bioinformatics, Ghent University, 9052 Ghent, Belgium; [email protected] 4 Center for Plant Systems Biology, VIB, 9052 Ghent, Belgium 5 Department of Biochemistry, Genetics and Microbiology, University of Pretoria, Pretoria 0028, South Africa 6 Faculty of Dental Medicine, Center for Interdisciplinary Research in Health (CIIS), Universidade Católica Portuguesa, Estrada da Circunvalação, 3504-505 Viseu, Portugal; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +351-234-370-766 Received: 28 October 2019; Accepted: 29 November 2019; Published: 3 December 2019 Abstract: Lasiodiplodia theobromae is one of the most aggressive agents of the grapevine trunk disease Botryosphaeria dieback. Through a dual RNA-sequencing approach, this study aimed to give a broader perspective on the infection strategy deployed by L. theobromae, while understanding grapevine response. Approximately 0.05% and 90% of the reads were mapped to the genomes of L. -

The Muscadine Grape (Vitis Rotundifolia Michx)1 Peter C

HS763 The Muscadine Grape (Vitis rotundifolia Michx)1 Peter C. Andersen, Ali Sarkhosh, Dustin Huff, and Jacque Breman2 Introduction from improved selections, and in fact, one that has been found in the Scuppernong River of North Carolina has The muscadine grape is native to the southeastern United been named ‘Scuppernong’. There are over 100 improved States and was the first native grape species to be cultivated cultivars of muscadine grapes that vary in size from 1/4 to in North America (Figure 1). The natural range of musca- 1 ½ inches in diameter and 4 to 15 grams in weight. Skin dine grapes extends from Delaware to central Florida and color ranges from light bronze to pink to purple to black. occurs in all states along the Gulf Coast to east Texas. It also Flesh is clear and translucent for all muscadine grape extends northward along the Mississippi River to Missouri. berries. Muscadine grapes will perform well throughout Florida, although performance is poor in calcareous soils or in soils with very poor drainage. Most scientists divide the Vitis ge- nus into two subgenera: Euvitis (the European, Vitis vinifera L. grapes and the American bunch grapes, Vitis labrusca L.) and the Muscadania grapes (muscadine grapes). There are three species within the Muscadania subgenera (Vitis munsoniana, Vitis popenoei and Vitis rotundifolia). Euvitis and Muscadania have somatic chromosome numbers of 38 and 40, respectively. Vines do best in deep, fertile soils, and they can often be found in adjacent riverbeds. Wild muscadine grapes are functionally dioecious due to incomplete stamen formation in female vines and incom- plete pistil formation in male vines. -

Measuring Microclimate Variations in Two Australian Feedlots

Measuring Microclimate Variations In Two Australian Feedlots Project number FLOT.310 Final Report prepared for MLA by: E.A. Systems Pty Limited PO Box W1029 16 Queen Elizabeth Drive ARMIDALE NSW 2350 Meat and Livestock Australia Ltd Locked Bag 991 North Sydney NSW 2059 ISBN 1 74036 761 8 YSTEMS Pty Limited E.A. S Environmental & Agricultural Science & Engineering May 2001 MLA makes no representation as to the accuracy of any information or advice contained in this document and excludes all liability, whether in contract, tort (including negligence or breach of statutory duty) or otherwise as a result of reliance by any person on such information or advice. MLA © 2004 ABN 39 081 678 364 1 Measuring Microclimate Variations in Two Australian Feedlots ABSTRACT Heat stress has caused catastrophic stock losses infrequently in Australia and does cause production losses over summers. While a considerable body of research has been undertaken on defining heat stress with respect to cattle comfort, health and production, few data are available on the micrometeorological characteristics of feedlots, shaded pens in feedlots and differences between feedlots and their surrounds. A study was undertaken to define these microclimates and therefore to identify the probable causes of heat stress. The study found that feedlot climates are different to their surrounds. Generally they are hotter and more humid and have lower wind speeds under shade. The study found that shade benefit cattle by reducing radiation heat loads but have the deleterious effects of increasing manure moisture contents, relative humidity and ammonia levels. Ammonia is identified as a possible stressor but its importance must be further defined. -

Victoria Mara Heilweil Photographic Artist, Curator, Educator 3270 20Th Street San Francisco, CA 94110

Victoria Mara Heilweil Photographic Artist, Curator, Educator 3270 20th Street San Francisco, CA 94110 (510) 918-4631 [email protected] www.victoriaheilweil.com Education 1995 MFA PHOTOGRAPHY California College of Arts and Crafts, Oakland, CA 1987 BFA FILM AND VIDEO New York University, New York, NY Recent Exhibitions 2019 BONE BLACK, group exhibition, DZINE Gallery, San Francisco, CA TEMPLE OF DIRECTION, group exhibition in collaboration with Phil Spitler, Burning Man Festival, Black Rock City, NV WATER MUSIC, group exhibition, DZINE Gallery, San Francisco, CA ORDINARY, group exhibition, Art Works Downtown, San Rafael, CA 2018 REASON AND REVERIE, group exhibition, Natalie and James Thompson Gallery, San Jose State University, CA Curator: Aaron Wilder DROP, solo exhibition, Art Works Downtown, San Rafael, CA EXPOSURE 2018: TO THOSE WHO SERVE, group exhibition, New Hope Arts, New Hope, PA WONDERSPACES, group exhibition in collaboration with Phil Spitler, San Diego, CA stARTup Art Fair, San Francisco, CA CURATED FRIDGE WINTER 2018, group exhibition, Cambridge, MA Juror: J. Sybylla Smith IMOTIF, group exhibition, Sohn Fine Art Gallery, Lenox, MA WHAT KEEPS YOU UP AT NIGHT?, group exhibition, Mendocino College Art Gallery, Ukiah, CA Curator: Tomiko Jones 2017 SIZE MATTERS, group exhibition, Helmuth Projects in conjunction with Medium Festival of Photography, San Diego, CA Juror: Katherine Ware, Photography Curator, Santa Fe Museum of Art COMMUNITY SOURCE(D), solo exhibition in collaboration with Mobile Arts Platform: Peter Foucault -

Doppler Lidar Measurements of Boundary Layer Heights Over San Jose, California

San Jose State University SJSU ScholarWorks Master's Theses Master's Theses and Graduate Research Fall 2017 Doppler LiDAR Measurements of Boundary Layer Heights Over San Jose, California Matthew Robert Lloyd San Jose State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/etd_theses Recommended Citation Lloyd, Matthew Robert, "Doppler LiDAR Measurements of Boundary Layer Heights Over San Jose, California" (2017). Master's Theses. 4880. DOI: https://doi.org/10.31979/etd.w6tv-6x88 https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/etd_theses/4880 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Master's Theses and Graduate Research at SJSU ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of SJSU ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DOPPLER LIDAR MEASUREMENTS OF BOUNDARY LAYER HEIGHTS OVER SAN JOSE, CALIFORNIA A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of Meteorology and Climate Science San José State University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science by Matthew R. Lloyd December 2017 © 2017 Matthew R. Lloyd ALL RIGHTS RESERVED The Designated Thesis Committee Approves the Thesis Titled DOPPLER LIDAR MEASUREMENTS OF BOUNDARY LAYER HEIGHTS OVER SAN JOSE, CALIFORNIA by Matthew R. Lloyd APPROVED FOR THE DEPARTMENT OF METEOROLOGY AND CLIMATE SCIENCE SAN JOSÉ STATE UNIVERSITY December 2017 Dr. Craig Clements Department of Meteorology and Climate Science Dr. Martin Leach Department of Meteorology and Climate Science Dr. Neil Lareau Department of Meteorology and Climate Science ABSTRACT DOPPLER LIDAR MEASUREMENTS OF BOUNDARY LAYER HEIGHTS OVER SAN JOSE, CALIFORNIA by Matthew R.