Sezela Mill Area •

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Provincial Road Network Hibiscus Coast Local Municipality (KZ216)

O O O L L Etsheni P Sibukosethu Dunstan L L Kwafica 0 1 L 0 2 0 1 0 3 0 3 74 9 3 0 02 2 6 3 4 L1 .! 3 D923 0 Farrell 3 33 2 3 5 0 Icabhane 6 L0 4 D 5 2 L 3 7 8 3 O O 92 0 9 0 L Hospital 64 O 8 Empola P D D 1 5 5 18 33 L 951 9 L 9 D 0 0 D 23 D 1 OL 3 4 4 3 Mayiyana S 5 5 3 4 O 2 3 L 3 0 5 3 3 9 Gobhela 2 3 Dingezweni P 5 D 0 8 Rosettenville 4 L 1 8 O Khakhamela P 1 6 9 L 1 2 8 3 6 1 28 2 P 0 L 1 9 P L 2 1 6 O 1 0 8 1 1 - 8 D 1 KZN211L P6 19 8-2 P 1 P 3 0 3 3 3 9 3 -2 2 3 2 4 Kwazamokuhle HP - 2 L182 0 0 D Mvuthuluka S 9 1 N 0 L L 1 3 O 115 D -2 O D1113 N2 KZN212 D D D 9 1 1 1 Catalina Bay 1 Baphumlile CP 4 1 1 P2 1 7 7 9 8 !. D 6 5 10 Umswilili JP L 9 D 5 7 9 0 Sibongimfundo Velimemeze 2 4 3 6 Sojuba Mtumaseli S D 2 0 5 9 4 42 L 9 Mzingelwa SP 23 2 D 0 O O OL 1 O KZN213 L L 0 0 O L 2 3 2 L 1 2 Kwahlongwa P 7 3 Slavu LP 0 0 2 2 O 7 L02 7 3 32 R102 6 7 5 3 Buhlebethu S D45 7 P6 8-2 KZN214 Umzumbe JP St Conrad Incancala C Nkelamandla P 8 9 4 1 9 Maluxhakha P 9 D D KZN215 3 2 .! 50 - D2 Ngawa JS D 2 Hibberdene KwaManqguzuka 9 Woodgrange P N KZN216 !. -

Border Water Scheme, Harry Gwala District Municipality, Kwazulu-Natal

CONSTRUCTION OF MTWALUME DAM, VULAMEHLO CROSS- BORDER WATER SCHEME, HARRY GWALA DISTRICT MUNICIPALITY, KWAZULU-NATAL Environmental Impact Assessment Report Authority Reference Number: DC43/0020/2014 June 2016 Draft Prepared for: Ugu District Municipality Title and Approval Page Construction of Mtwalume Dam, Vulamehlo Cross Border Water Scheme, Project Name: Harry Gwala District Municipality, KwaZulu-Natal Report Title: Environmental Impact Assessment Report Authority Reference: DC43/0020/2014 Report Status : Draft Applicant: Ugu District Municipality Prepared By: Nemai Consulting +27 11 781 1730 147 Bram Fischer Drive, +27 11 781 1730 FERNDALE, 2194 [email protected] PO Box 1673, SUNNINGHILL, www.nemai.co.za 2157 Report Reference: 10550-20160603-Draft EIA Report R-PRO-REP|20150514 Authorisation Name Signature Date Author: Kristy Robertson 20160602 Reviewed By: Donavan Henning 20160603 This Document is Confidential Intellectual Property of Nemai Consulting C.C. © copyright and all other rights reserved by Nemai Consulting C.C. This document may only be used for its intended purpose Proposed Mtwalume Dam EIA Report Draft Amendments Page Amendment Date: Nature of Amendment Number: 20160408 First Draft for Internal Review 00 20160512 First Draft for Client Review 01 20160603 Second Draft for Client Review 02 20160614 First Draft for Public and Authority Review 03 Proposed Mtwalume Dam EIA Report Draft Executive Summary PROJECT BACKGROUND AND MOTIVATION The Ugu District Municipality (DM) owns and operates the Vulamehlo Water Treatment Plant (WTP) which supplies potable water to areas within the Vulamehlo and Umzumbe Local Municipalities in Ugu District Municipality as well as to areas within the Ubuhlebezwe Local Municipality in Harry Gwala District Municipality. -

Kwazulu-Natal Coastal Erosion Events of 2006/2007 And

Research Letter KwaZulu-Natal coastal erosion: A predictive tool? Page 1 of 4 KwaZulu-Natal coastal erosion events of 2006/2007 AUTHORS: and 2011: A predictive tool? Alan Smith' Lisa A. Guastella^ Severe coastal erosion occurred along the KwaZulu-Natal coastline between mid-May and November 2011. Andrew A. Mather^ Analysis of this erosion event and comparison with previous coastal erosion events in 2006/2007 offered the Simon C. Bundy" opportunity to extend the understanding of the time and place of coastal erosion strikes. The swells that drove Ivan D. Haigh* the erosion hotspots of the 2011 erosion season were relatively low (significant wave heights were between AFFILIATIONS: 2 m and 4.5 m) but ot long duration. Although swell height was important, swell-propagation direction and 'School of Geological Sciences, particularly swell duration played a dominant role in driving the 2011 erosion event. Two erosion hotspot types University of KwaZulu-Natal, were noted: sandy beaches underlain by shallow bedrock and thick sandy beaches. The former are triggered Durban, South Africa by high swells (as in March 2007) and austral winter erosion events (such as in 2006, 2007 and 2011). ^Oceanography Department, University of Cape Town, Cape The latter become evident later in the austral winter erosion cycle. Both types were associated with subtidal Town, South Africa shore-normal channels seaward of megacusps, themselves linked to megarip current heads. This 2011 ^Ethekwini Municipality, Durban, coastal erosion event occurred during a year in which the lunar perigee sub-harmonic cycle (a ±4.4-year South Africa cycle) peaked, a pattern which appears to have recurred on the KwaZulu-Natal coast. -

Assessment of the Proposed Africa Lime Quarry Near Port Shepstone, Hibiscuss Coast Local Municipality, Kzn

Limestone Quarry PHASE ONE HERITAGE IMPACT ASSESSMENT OF THE PROPOSED AFRICA LIME QUARRY NEAR PORT SHEPSTONE, HIBISCUSS COAST LOCAL MUNICIPALITY, KZN ACTIVE HERITAGE cc. For: EnviroPro Frans Prins MA (Archaeology) P.O. Box 947 Howick 3290 [email protected] [email protected] www.activeheritage.webs.com 27 March 2019 Fax: 086 7636380 Details and experience of independent Heritage Impact Assessment Consultant Active Heritage cc for EnviroPro i Limestone Quarry Consultant: Frans Prins (Active Heritage cc) Contact person: Frans Prins Physical address: 33 Buchanan Street, Howick, 3290 Postal address: P O Box 947, Howick, 3290 Telephone: +27 033 3307729 Mobile: +27 0834739657 Fax: 0867636380 Email: [email protected] PhD candidate (Anthropology) University of KwaZulu-Natal MA (Archaeology) University of Stellenbosch 1991 Hons (Archaeology) University of Stellenbosch 1989 University of KwaZulu-Natal, Honorary Lecturer (School of Anthropology, Gender and Historical Studies). Association of Southern African Professional Archaeologists member Frans received his MA (Archaeology) from the University of Stellenbosch and is presently a PhD candidate on social anthropology at Rhodes University. His PhD research topic deals with indigenous San perceptions and interactions with the rock art heritage of the Drakensberg. Frans was employed as a junior research associate at the then University of Transkei, Botany Department in 1988-1990. Although attached to a Botany Department he conducted a palaeoecological study on the Iron Age of northern Transkei - this study formed the basis for his MA thesis in Archaeology. Frans left the University of Transkei to accept a junior lecturing position at the University of Stellenbosch in 1990. He taught mostly undergraduate courses on World Archaeology and research methodology during this period. -

South Coast System

Infrastructure Master Plan 2020 2020/2021 – 2050/2051 Volume 4: South Coast System Infrastructure Development Division, Umgeni Water 310 Burger Street, Pietermaritzburg, 3201, Republic of South Africa P.O. Box 9, Pietermaritzburg, 3200, Republic of South Africa Tel: +27 (33) 341 1111 / Fax +27 (33) 341 1167 / Toll free: 0800 331 820 Think Water, Email: [email protected] / Web: www.umgeni.co.za think Umgeni Water. Improving Quality of Life and Enhancing Sustainable Economic Development. For further information, please contact: Planning Services Infrastructure Development Division Umgeni Water P.O.Box 9, Pietermaritzburg, 3200 KwaZulu‐Natal, South Africa Tel: 033 341‐1522 Fax: 033 341‐1218 Email: [email protected] Web: www.umgeni.co.za PREFACE This Infrastructure Master Plan 2020 describes: Umgeni Water’s infrastructure plans for the financial period 2020/2021 – 2050/2051, and Infrastructure master plans for other areas outside of Umgeni Water’s Operating Area but within KwaZulu-Natal. It is a comprehensive technical report that provides information on current infrastructure and on future infrastructure development plans. This report replaces the last comprehensive Infrastructure Master Plan that was compiled in 2019 and which only pertained to the Umgeni Water Operational area. The report is divided into ten volumes as per the organogram below. Volume 1 includes the following sections and a description of each is provided below: Section 2 describes the most recent changes and trends within the primary environmental dictates that influence development plans within the province. Section 3 relates only to the Umgeni Water Operational Areas and provides a review of historic water sales against past projections, as well as Umgeni Water’s most recent water demand projections, compiled at the end of 2019. -

Historical National Landmark Property St Elmo's, Umzumbe, Kwa Zulu-Natal

HISTORICAL NATIONAL LANDMARK ON PROPERTY AUCTION ST ELMO’S, UMZUMBE, KWA ZULU-NATAL SOUTH COAST WEB#: AUCT-000099 | www.in2assets.com ADDRESS: St Elmo’s, Golf View Road, Umzumbe, KwaZulu-Natal South Coast AUCTION VENUE: The Durban Country Club, Isaiah Ntshangase Road, Durban AUCTION DATE & TIME: 12 November 2015 | 11h00 VIEWING: By Appointment CONTACT: Rainer Stenzhorn | 082 321 1135 | 031 574 7600 | [email protected] REGISTRATION FEE: R 50 000-00 (Refundable Bank Guaranteed Cheque) AUCTIONEER: Andrew Miller The Rules of Auction can be viewed at www.In2assets.com or at Unit 504, 5th Floor, Strauss Daly Place, 41 Richefond Circle, Ridgeside Office Park, Umhlanga Ridge. Bidders must register to bid and provide original proof of identity and residence on registration. The Rules of Auction contain the registration requirements if you intend to bid on behalf of another person or an entity. The above property is subject to a reserve price and the sale by auction is subject to a right to bid by or on behalf of the owner or auctioneer. ST ELMO’S, GOLF VIEW ROAD, UMZUMBE, CONTENTS KWAZULU-NATAL SOUTH COAST 1318 Old North Coast Road, Avoca CPA LETTER 2 PROPERTY DESCRIPTION 3 PROPERTY LOCATION 4 PICTURE GALLERY 5 ADDITIONAL INFORMATION 7 TERMS AND CONDITIONS 17 ZONING INFORMATION – THE REMAINDER OF ERF 91 UMZUMBE 18 ZONING INFORMATION - FOR THE PROPOSED SUB 2 OF ERF 91 UMZUMBE 21 SG DIAGRAMS 26 TITLE DEED 30 PROPOSED FLOOR PLANS 35 DISCLAIMER: Whilst all reasonable care has been taken to provide accurate information, neither of In2assets Properties (Pty) Ltd nor the Seller/s guarantee the correctness of the information, provided herein and neither will be held liable for any direct or indirect damages or loss, of whatsoever nature, suffered by any person as a result of errors or omissions in the information provided, whether due to the negligence or otherwise of In2assets Properties (Pty) Ltd or the Sellers or any other person. -

Integrated Development Plan (IDP)

Content Page 1. Introduction 04 2. Community and Stakeholder Participation 06 2.1. Ward Based Community Participation 06 3. The Context 07 3.1. Millennium Development Goals 07 3.2. National Directives 08 3.2.1. Vision 2014 08 3.2.2. National Spatial Development Perspectives 10 3.2.3. State of The Nation Address 11 3.3. Provincial Directives 12 3.3.1. Provincial Growth and Development Strategy 12 3.3.2. Provincial Spatial Economic Development Strategy 12 SITUATIONAL ANALYSIS 13 1. Basic Municipal Information 13 1.1. Population 14 2. Topography 17 3. Infrastructure and Services 17 3.1. Roads 17 3.1.1. Urban Roads 18 3.1.2. Rural Roads 18 3.1.2.1. Public Inputs 19 3.2. Drainage 3.3. water 20 3.3.1. Public Inputs 21 3.4. Sanitation 22 3.4.1. Public Inputs 23 1 3.5. Housing 23 3.6. Waste Removal 24 3.7. Electricity 25 3.7.1. Public Inputs 25 4. Overview of The Socio-Economic Analysis 26 4.1. Health 27 4.1.1. facilities 27 4.1.2. HIV AND AIDS 28 4.2. Education 29 4.3. Sports and Recreation 30 4.4. Community Facilities 30 4.5. Social Services 31 4.6. Economic Development 32 4.6.1. LED Strategy 32 4.6.2. Household Income 32 4.6.3. Economic Structure 34 5. Institutional Analysis 37 5.1. Municipal Structure 37 5.2. Structural Problems 39 5.3. Skills Development 40 5.4. Organizational Reengineering 41 5.5. Financial Management 41 5.5.1. -

935 25-4 Kznseparate Layout 1

KWAZULU-NATAL PROVINCE RKEPUBLICWAZULU-NATAL PROVINSIEREPUBLIIEK OF VAN SOUTHISIFUNDAZWEAFRICA SAKWAZULUSUID-NATALI-AFRIKA Provincial Gazette • Provinsiale Koerant • Igazethi Yesifundazwe GAZETTE EXTRAORDINARY—BUITENGEWONE KOERANT—IGAZETHI EYISIPESHELI (Registered at the post office as a newspaper) • (As ’n nuusblad by die poskantoor geregistreer) (Irejistiwee njengephephandaba eposihhovisi) PIETERMARITZBURG, 25 APRIL 2013 Vol. 7 25 kuMBASA 2013 No. 935 Ule ail bovv s the pow 's; to prevent APOS (-WS HER!NE 0800 012 322 DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH Prevention is the cure N.B. The Government Printing Works will not be held responsible for the quality of “Hard Copies” or “Electronic Files” submitted for publication purposes 301725—A 935—1 2 Extraordinary Provincial Gazette of KwaZulu-Natal 25 April 2013 IMPORTANT NOTICE The Government Printing Works will not be held responsible for faxed documents not received due to errors on the fax machine or faxes received which are unclear or incomplete. Please be advised that an “OK” slip, received from a fax machine, will not be accepted as proof that documents were received by the GPW for printing. If documents are faxed to the GPW it will be the senderʼs respon- sibility to phone and confirm that the documents were received in good order. Furthermore the Government Printing Works will also not be held responsible for cancellations and amendments which have not been done on original documents received from clients. CONTENTS INHOUD No. Bladsy No. Page PROVINCIAL NOTICE PROVINSIALE KENNISGEWING 52 KwaZulu-Natal Gaming and Betting Board: 52 KwaZulu-Natal Dobbelary en Weddery Notice of applications received ..................... 3 Raad: Kennis van aansoeke ontvang........... 13 No. Ikhasi ISAZISO SESIFUNDAZWE 52 Ibhodi yezokuGembula yaKwaZulu-Natali: Isaziso ngezicelo ezamukeliwe ........................................................... -

Provinciai Gazette • Provinsiaie Koerant • I9azethi Yesifundazwe

::::;::: ::; ::::::::: ::::::::::: ~~ ~ !! i\i(~ provinciaI Gazette • Provins iaIe Koerant • I9azethi Yes if und azwe GAZETTE EXT RAOR01NARY-BUITENGEWONE KO ERANT-IGAZETHI EYIS1PESHELI (Registered at the post office as a newspaper) • (As 'n nuusblad by die poskantoor geregistr66r) (Irejistiwee njengephephandaba eposihhovisi) p IETERMARITZBURG, 27 A UG U ST 2009 27 A UGU STUS 2009 VaI. 3 27 kuN C WABA 2009 N0 . 324 2 Extraordinary Provincial Gazette of KwaZu/u-Natal 27 August 2009 Page No. ADVERTISEMENT Road Carrier Permits, Pietermaritzburg......................................................................................................................... 3 27 August 2009 Extraordinary Provincial Gazette of KwaZulu-Natal 3 APPLICATION FOR PUBLIC ROAD CARRIER PERMITS OR OPERATING LICENCES Notice is hereby given in terms of section 37(1)(a) of the National Land Transport Transition Act, and section 52 (1) KZN Public Transport Act (Act 3 of 2005) of the particulars in respect of application for public road carrier permits and lor operating licences received by the KZN Public Transport Licensing Board, indicating: - (1) The application number; (2) The name and identity number of the applicant; (3) The place where the applicant conducts his business or wishes to conduct his business, as well as his postal address; (4) The nature of the application, that is whether it is an application for: - .(4.1) the grant of a new permit or operating licence; (4.2) the grant of additional authorisation; (4.3) the amendment of route; (4.4) the amendment -

Provincial Road Network Umdoni Local Municipality (KZN212)

O L P 0 2 0 D 5 0 2 8 0 1 D 0 5 0 5 5 1 3 9 8 0 2 0 7 5 L 93 2 3 O 0 0 5 L 2 5, 8 O 177 9 D 8 3 3 3 2 8 24 7 2 D Ellingham P 5 9 - D 3 2 P 7 4 8 N 2 2 - OL02 95 W 0 2 2 804 85 !. 3 Sizomunye P O L N 7 O 0 L 2 O 0 D R 9 2 7 80 7 6 P 7 Ilfracombe D P 3 2 529 971 0 Ellinghata LP 7 D L Dududu D O R102 Phindavele !. OL0 M 2771 k Zembeni Indududu om az i -2 Dududu Provincial Clinic 3 79 P 027 O P OL L0 88 27 KZN211 80 6 79 02 Craigieburn Local Authority Clinic OL Naidoo Memorial P 3 4 OL 1 0 D 1 Sukamuva 28 20 4 5 P P 7 D 1 Umkomaas S 7 9 7 4 Umkomaas P P78 Umkomaas Local Authority Clinic !. 0 Umkomaas 9 7 KZN212 2 O 0 Naidooville P 9 L N O - R P 346 1 D2276 A M 8 M A 7 Craigieburn 2 P R 0 !. - L F O F O 176 9 8 7 2 0 94 L O KZN213 Macebo LP 65 189 5 7 9 D Widenham !. 1 2 D 7 L 96 1 0 6 9 Kwamaquza LP KZN214 Zitlokozise JS D 1 1 9 0 1 2 8 O 2 0 L L 0 O 7 1 2 8 8 99 9 1 2 2 0 0 1 0 8 1 L 2 2 1 O 0 D 4 L 1 8 O 2 0 L KZN215 O Ikhakhama Celokuhle HP Kwa-Hluzingqondo Amahlongwa LP Nomazwe O Injabulo HP L0 OL02824 28 18 KZN216 O 73 L 0 0 D1 2 8 Ntontonto 2 6 782 OL02 5 2 8 2 0 L O D1103 104 Mah longw 9 a O 2 O L 8 L0 0 2 2 2 0 82 8 L 8 33 2 O O 7 L 0 2 7 7 O 1 9 L Philani Provincial Clinic 9 2 0 2 7 2 0 8 7 O L 8 9 2 O O 3 L 8 0 0 L L 9 1 2 Clansthal 1 0 O 9 9 9 2 2 2 !. -

Hibiscus Coast Municipality Housing Sector Plan

Hibiscus Coast Housing Development Plan HIBISCUS COAST MUNICIPALITY HOUSING SECTOR PLAN PREPARED BY: ISIPHETHU DEVELOPMENT CONSULTANTS 1 Hibiscus Coast Housing Development Plan TABLE OF CONTENTS ITEM PAGE NO. 1. Executive Summary 5 -7 2. Methodology 8 2.1 Literature review 8 2.2 Consultative process 9 3. Hibiscus Coast Municipality Local Context 10 3.1 Hibiscus Coast Municipality location 10 3.2 Background and demographics 11 -13 3.3 Vision, Principles and Mission 14 3.4 Hibiscus Coast Municipality Spatial Framework 15-17 3.5 Information on housing typologies for HCM 18-19 4. Alignment with other municipal and government programmes and policies 20 4.1 Integrated Development Plan 20 4.2 Community upliftment and empowerment of rural Areas 20 4.3 Economic development and investment attraction 21 4.4 Provincial Spatial Economic Development Strategy 21 4.5 Implementation of housing projects through Extended Public Works programme 22 4.6 Integrated Sustainable Rural Development Programme 23 5. Background overview and current reality 25 5.1 National Perspective 25 5.2 KwaZulu Natal Provincial Perspective 26 5.3 Hibiscus Coast Municipality perspective 29 6. Land identification 30 -34 7. Information on Hibiscus Coast Current Housing Projects 35 7.1 Current and completed Housing Projects 35 7.2 Budget and Cash flows for current projects 40 7.3 Planned Projects and budget and cash flow 42 8. Integration with other sectors 44 2 Hibiscus Coast Housing Development Plan 8.1 District Infrastructure Planning 45 9 Housing Delivery plan 49 10 Performance measurement 52 11 Institutional arrangements and skills transfer 55 12 Housing issues and strategic framework 58 13 Conclusion 60 14 References 61 15 Annexures 62 151. -

Export This Category As A

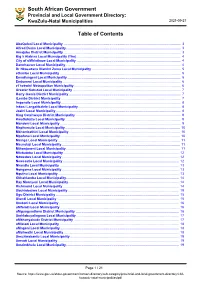

South African Government Provincial and Local Government Directory: KwaZulu-Natal Municipalities 2021-09-27 Table of Contents AbaQulusi Local Municipality .............................................................................................................................. 3 Alfred Duma Local Municipality ........................................................................................................................... 3 Amajuba District Municipality .............................................................................................................................. 3 Big 5 Hlabisa Local Municipality (The) ................................................................................................................ 4 City of uMhlathuze Local Municipality ................................................................................................................ 4 Dannhauser Local Municipality ............................................................................................................................ 4 Dr Nkosazana Dlamini Zuma Local Municipality ................................................................................................ 5 eDumbe Local Municipality .................................................................................................................................. 5 Emadlangeni Local Municipality .......................................................................................................................... 6 Endumeni Local Municipality ..............................................................................................................................