Table of Contents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DR. BONNY NORTON, FRSC Professor and Distinguished University Scholar Department of Language and Literacy Education (LLED) University of British Columbia

DR. BONNY NORTON, FRSC Professor and Distinguished University Scholar Department of Language and Literacy Education (LLED) University of British Columbia Research Advisor, African Storybook Research Lead, Storybooks Canada http://faculty.educ.ubc.ca/norton/ Contact: [email protected] Degrees • PhD, University of Toronto: Language Education, 1993. (SSHRC Doctoral Fellow) • MA, Reading University, UK: Theoretical Linguistics, 1984. (Rotary Graduate Scholar) • BA Hons, Univ. of Witwatersrand, SA: Applied Linguistics, 1982. (Ranked 1 in program) • BA HDipEd, University of Witwatersrand, SA, 1978: English and History. • BA, Univ. of Witwatersrand, SA: English & History, 1977. (Ranked 1 in History program) Career • Professor and Distinguished University Scholar, LLED, UBC, 2004 – present • Assistant/Associate Professor, Language and Literacy Education, UBC, 1996-2004 • USA Spencer Postdoctoral Fellow, McMaster University, 1995-1996 • SSHRC Postdoctoral Fellow, University of Witwatersrand and Toronto, 1993-1995 • Language Tester, Educational Testing Service, Princeton, NJ, 1984-1987 • Language Tutor, Linguistics Department, University of Witwatersrand, SA, 1980-1983 • English and History Teacher, Johannesburg, SA, 1979 Awards and Distinctions • UBC Great Supervisor, 2017 • Fellow, Royal Society of Canada, 2016 • TESOL Distinguished Research Award (co-recipient), USA, 2016 • Distinguished Visiting Scholar, Beijing Foreign Studies University, China, 2015 • Pack Distinguished Scholar and Convocation Speaker, Otterbein University, USA, 2015 • -

Issues in Applied Linguistics

UCLA Issues in Applied Linguistics Title The Practice of Theory in the Language Classroom Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/2s36f41d Journal Issues in Applied Linguistics, 18(2) ISSN 1050-4273 Author Norton, Bonny Publication Date 2010 DOI 10.5070/L4182005336 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California The Practice of Theory in the Language Classroom Bonny Norton University of British Columbia In this article, the author makes the case that poststructuralist theories of language, identity, and investment can be highly relevant for the practical deci- sion-making of language teachers, administrators and policy makers. She draws on her research in the international community to argue that while markers of identity such as accent, race, and gender impact the relationship between teach- ers and students, what is of far greater importance are the teachers’ pedagogical practices. This research suggests that language teaching is most effective when the teacher recognizes the multiple identities of students, and develops peda- gogical practices that enhance students’ investment in the language practices of the classroom. The author concludes that administrators and policy makers need to be supportive of language teachers as they seek to be more effective in linguistically diverse classrooms. Introduction One of the icons of language teaching in Canada, Mary Ashworth, was often heard to comment, “There is nothing as practical as a good theory.” As the United States struggles to adjust to the challenges and possibilities of linguistic diversity in American classrooms, and how research should inform educational policy mak- ing, I wish to bring theory back into the debate. -

Tesol Quarterly

TABLE OF CONTENTS QUARTERLY A Journal for Teachers of English to Speakers of Other Languages and of Standard English as a Second Dialect Editor SANDRA McKAY, San Francisco State University Guest Editors NANCY H. HORNBERGER, University of Pennsylvania THOMAS R. RICENTO, University of Texas at San Antonio Teaching Issues Editor BONNY NORTON PEIRCE, University of British Columbia Brief Reports and Summaries Guest Editors NANCY H. HORNBERGER, University of Pennsylvania THOMAS K. RICENTO, University of Texas at San Antonio Review Guest Editors NANCY H. HORNBERGER, University of Pennsylvania THOMAS R. RICENTO, University of Texas at San Antonio Assistant Editor ELLEN GARSHICK, TESOL Central Office Editorial Assistant CATHERINE HARTMAN, San Francisco State University Editorial Advisory Board Lyle Bachman, B. Kumaravadivelu, University of California, Los Angeles San Jose State University Kathleen Bardovi-Harlig, Patsy M. Lightbown, Indiana University Concordia University Ellen Block, Alastair Pennycook, Baruch College University of Melbourne Keith Chick, Patricia Porter, University of Natal San Francisco State University Deborah Curtis, Kamal Sridhar, San Francisco State University State University of New York Zoltàn Dörnyei, Terrence Wiley, Etövös University California State University, Sandra Fotos, Long Beach Senshu University Jerri Willett, Eli Hinkel, University of Massachusetts Xavier University at Amherst Nancy Hornberger, Vivian Zamel, University of Pennsylvania University of Massachusetts Additional Readers Christian J. Faltis, Joan Kelly Hall, R. Keith Johnson, Robert B. Kaplan, Brian Lynch, Mohamed Maamouri, Robert D. Milk, Margaret Van Naerssen, Roger W. Shuy, James W. Tollefson Credits Advertising arranged by Jennifer Delett, TESOL Central Office, Alexandria, Virginia U.S.A. Typesetting by Capitol Communication Systems, Inc., Crofton, Maryland U.S.A. -

Marketing Fragment 6 X 10.5.T65

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-82802-4 - Critical Pedagogies and Language Learning Edited by Bonny Norton and Kelleen Toohey Frontmatter More information Critical Pedagogies and Language Learning © Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-82802-4 - Critical Pedagogies and Language Learning Edited by Bonny Norton and Kelleen Toohey Frontmatter More information THE CAMBRIDGE APPLIED LINGUISTICS SERIES Series editors: Michael H. Long and Jack C. Richards This series presents the findings of work in applied linguistics that are of direct relevance to language teaching and learning and of particular interest to applied linguists, researchers, language teachers, and teacher trainers. Recent publications in this series: Cognition and Second Language Instruction edited by Peter Robinson Computer Applications in Second Language Acquisition by Carol A. Chapelle Contrastive Rhetoric by Ulla Connor Corpora in Applied Linguistics by Susan Hunston Criterion-referenced Language Testing by James Dean Brown and Thom Hudson Culture in Second Language Teaching and Learning edited by Eli Hinkel Exploring the Dynamics of Second Language Teaching edited by Barbara Kroll Exploring the Dynamics of Second Language Writing by Barbara Kroll Exploring the Second Language Mental Lexicon by David Singleton Focus on Form in Classroom Second Language Acquisition edited by Catherine Doughty and Jessica Williams Immersion Education: International Perspectives edited by Robert Keith Johnson and Merrill Swain Interfaces between Second Language Acquisition and Language Testing Research edited by Lyle F. Bachman and Andrew D. Cohen Learning Vocabulary in Another Language by I. S. P. Nation Network-based Language Teaching edited by Mark Warschauer and Richard Kern Pragmatics in Language Teaching edited by Kenneth R. -

Download Download

1 MJ E The McGill Journal of Education promotes an international, multidisciplinary discussion of issues in the field of educational research, theory, and practice. We are committed to high quality scholarship in both English and French. As an open-access publication, freely available on the web (http://mje.mcgill.ca), the Journal reaches an international audience and encourages scholars and practitioners from around the world to submit manuscripts on relevant educational issues. La Revue des sciences de l’éducation de McGill favorise les échanges internationaux et plu- ridisciplinaires sur les sujets relevant de la recherche, de la théorie et de la pratique de l’éducation. Nous demeurons engagés envers un savoir de haute qualité en français et en anglais. Publication libre, accessible sur le Web (à http://mje.mcgill.ca), la Revue joint un lectorat international et invite les chercheurs et les praticiens du monde entier à lui faire parvenir leurs manuscrits traitant d’un sujet relié à l’éducation. International Standard Serial No./Numéro de série international: online ISSN 1916-0666 REPUBLICATION RIGHTS / DROITS DE REPRODUCTION All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be republished in any form or by any means without permission in writing from Copibec. Tous droits réservés. Aucune partie de la présente publication ne peut être reproduite sous quelque forme et par quelque moyen que ce soit sans l’autorisation écrite de Copibec. Copibec (reproduction papier) • 514 288 1664 • 1 800 717 2022 • • [email protected] © Faculty of Education, McGill Universisty McGill Journal of Education / Revue des sciences de l’éducation de McGill 4700 rue McTavish Street • Montréal (QC) • Canada H3G 1C6 •T: 514 398 4246 • F: 514 398 4529 • http://mje.mcgill.ca The McGill Journal of Education acknowledges the financial support of The Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. -

Language Learning, Social Identity, and Immigrant Women

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 373 582 FL 022 435 AUTHOR Peirce, Bonny Norton TITLE Language Learning, Social Identity, and Immigrant Women. PUB DATE Mar 94 NOTE 12p.; Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Teachers of English to Speakers of Other Languages (28th, Baltimore, MD, March 8-12, 1994). PUB TYPE Reports Research/Technical (143) Speeches /Conference -,._: (150) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Case Studies; English (Second Language); *Females; Feminism; Foreign Countries; *Immigrants; *Language Attitudes; *Linguistic Theory; Longitudinal Studies; *Power Structure; *Second Language Learning; Socioeconomic Influences; Student Attitudes IDENTIFIERS Canada; *Poststructuralism ABSTRACT This paper argues, using a feminist poststructuralist perspective, that second language acquisition (SLA) theorists have struggled to explore the relationship between the language learner and the social world because they do not question how structures of power in the social world impact on individual languagelearners and the opportunities they have to interact with target language speakers. It also reports on a study of the language learning experiences of five women immigrants to Canada. SLA theorists have failed to explore the extent to which sexism, racism, and elitism influence the kinds of opportunities second language learners have to practice the target language and how immigrant language learners are frequently marginalized by members of the target language community. The results of the case studies of immigrant women demonstrate that motivation, extroversion, and confidence are not fixed personality traits, but should be understood with reference to social relations of power that create the possibilities for language learners to speak. (Contains 17 references.) (MDM) Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. -

Compact UBC CV December 2017.Pdf

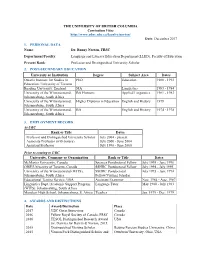

THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA Curriculum Vitae http://www.educ.ubc.ca/faculty/norton/ Date: December 2017 1. PERSONAL DATA Name: Dr. Bonny Norton, FRSC Department/Faculty: Language and Literacy Education Department (LLED), Faculty of Education Present Rank: Professor and Distinguished University Scholar 2. POST-SECONDARY EDUCATION University or Institution Degree Subject Area Dates Ontario Institute for Studies in PhD Education 1988 - 1993 Education, University of Toronto Reading University, England MA Linguistics 1983 - 1984 University of the Witwatersrand, BA Honours Applied Linguistics 1981 - 1982 Johannesburg, South Africa University of the Witwatersrand, Higher Diploma in Education English and History 1979 Johannesburg, South Africa University of the Witwatersrand, BA English and History 1974 - 1978 Johannesburg, South Africa 3. EMPLOYMENT RECORD At UBC Rank or Title Dates Professor and Distinguished University Scholar July 2004 - present Associate Professor (with tenure) July 2000 - June 2004 Assistant Professor July 1996 - June 2000 Prior to coming to UBC University, Company or Organization Rank or Title Dates McMaster University, Canada Spencer Postdoctoral Fellow July 1995 - June 1996 OISE/University of Toronto, Canada SSHRC Postdoctoral Fellow July 1994 - July 1995 University of the Witwatersrand (WITS), SSHRC Postdoctoral July 1993 - June 1994 Johannesburg, South Africa Fellow/Visiting Scholar Educational Testing Service, USA Assistant Examiner Nov. 1984 - Aug. 1987 Linguistics Dept./Academic Support Program, Language Tutor May 1980 - July 1983 (WITS), Johannesburg, South Africa Mondeor High School, Johannesburg, S. Africa Teacher Jan. 1979 - Dec. 1979 4. AWARDS AND DISTINCTIONS Date Award/Distinction Place 2017 UBC Great Supervisor Canada 2016 Fellow Royal Society of Canada, FRSC Canada 2016 TESOL Distinguished Research Award USA (w. -

Willy A. Renandya Handoyo Puji Widodo Editors Linking Theory and Practice

English Language Education Willy A. Renandya Handoyo Puji Widodo Editors English Language Teaching Today Linking Theory and Practice www.ebook3000.com English Language Education Volume 5 Series Editors Chris Davison, The University of New South Wales, Australia Xuesong Gao, The University of Hong Kong, China Editorial Advisory Board Stephen Andrews, University of Hong Kong, China Anne Burns, University of New South Wales, Australia Yuko Goto Butler, University of Pennsylvania, USA Suresh Canagarajah, Pennsylvania State University, USA Jim Cummins, OISE, University of Toronto, Canada Christine C. M. Goh, National Institute of Education, Nanyang Technology University, Singapore Margaret Hawkins, University of Wisconsin, USA Ouyang Huhua, Guangdong University of Foreign Studies, Guangzhou, China Andy Kirkpatrick, Griffi th University, Australia Michael K. Legutke, Justus Liebig University Giessen, Germany Constant Leung, King’s College London, University of London, UK Bonny Norton, University of British Columbia, Canada Elana Shohamy, Tel Aviv University, Israel Qiufang Wen, Beijing Foreign Studies University, Beijing, China Lawrence Jun Zhang, University of Auckland, New Zealand More information about this series at http://www.springer.com/series/11558 www.ebook3000.com Willy A. Renandya • Handoyo Puji Widodo Editors English Language Teaching Today Linking Theory and Practice Editors Willy A. Renandya Handoyo Puji Widodo Department of English Language & Department of English Literature, National Institute of Education Politeknik Negeri Jember Nanyang Technological University Jember , Jawa Timur , Indonesia Singapore , Singapore ISSN 2213-6967 ISSN 2213-6975 (electronic) English Language Education ISBN 978-3-319-38832-8 ISBN 978-3-319-38834-2 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-38834-2 Library of Congress Control Number: 2016947720 © Springer International Publishing Switzerland 2016 This work is subject to copyright. -

Critical Literacy, Language Learning, and Popular Culture Bonny Norton

The Language TeacherISSN 0289-7938 ¥950 JALT2006 Pre-Conference Special Issue • Plenary Speaker articles from: Donald Freeman, Yasuko Kanno, Lin Lougheed, and Bonny Norton • Featured Speaker articles from: Steve Brown, Sara Cotterall, Nicholas Groom, Marc Helgesen, Don Maybin, Jack C. Richards, Bruce Rogers, Brian Tomlinson, Grant Trew, Rob Waring, and Shoko Yoneyama July, 2006 • Volume 30, Number 7 The Japan Association for Language Teaching THE JAPAN ASSOCIATION FOR LANGUAGE TEACHING 全国語学教育学会 J全 国 語 学 教 育 学 会ALT — Pre-Conference Workshops — A chance to "Skill-Up" before JALT2006 starts! 14:00 – 18:00, Thu, 2 Nov, 2005 For JALT2006, we will be running pre-conference workshops aimed at helping teachers develop their professional skills. This year, we are offering three workshops – one on storytelling, and the other two on basic computer skills. They will be held on Thu 2 Nov, 14:00-18:00. Registration will be by pre- registration only and will be on a first-come-first-served basis. Please register when you complete your conference pre-registration. A maximum of 25 people will be accepted for each workshop. The cost is ¥4,000 (members) or ¥5,000 (non-members) for any one of the workshops. Workshop 1: Storytelling technique for language teachers —Charles Kowalski Language teachers, working with all age groups and proficiency levels, have increasingly been taking an interest in using storytelling in their classes, but many hesitate because of doubts about their own ability as storytellers. However, storytelling does not require Academy Award-level theatrics, only effective use of the storyteller’s natural talents. -

Identity and Language Learning: Gender, Ethnicity and Educational Change

Identity and Language Learning IALA01 1 18/3/13, 04:59 PM LANGUAGE IN SOCIAL LIFE SERIES Series Editor: Professor Christopher N Candlin Chair Professor of Applied Linguistics Department of English Centre for English Language Education & Communication Research City University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong For a complete list of books in this series see pages v and vi IALA01 2 18/3/13, 04:59 PM Identity and Language Learning: Gender, Ethnicity and Educational Change Bonny Norton IALA01 3 18/3/13, 04:59 PM Pearson Education Limited Edinburgh Gate Harlow Essex CM20 2JE England and Associated Companies throughout the world Visit us on the World Wide Web at: www.pearsoneduc.com First published 2000 © Pearson Education Limited 2000 The right of Bonny Norton to be identified as author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved; no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without either the prior written permission of the Publishers or a licence permitting restricted copying in the United Kingdom issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency Ltd, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W1P 0LP ISBN 0-582-38225-4 CSD ISBN 0-582-38224-6 PPR British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Norton, Bonny, 1956– Identity and language learning: social processes and educational practice / Bonny Norton.