Oren Lyons Interview

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Haudenosaunee Story

Column One: Imagine inventing a sport and then being shunned by it. That's the Haudenosaunee story David Wharton , LA Times•August 21, 2020 The Haudenosaunee invented the sport of lacrosse, though they say lacrosse is a gift from the creator. (Iroquois Nationals Archives) More Before all the haggling, the ugly words and political machinations, there was a happier story. The way the Haudenosaunee people tell it, the animals of the forest gathered for a great ballgame. The powerful bear and swift deer led one team; on the other side stood the hawk, eagle and owl. Just before the start, a mouse and squirrel approached the birds, asking to join in. It seems they had been rejected by the larger four-legged animals because of their size. The birds welcomed them. This ancestral tale serves as a metaphor for the Haudenosaunee, a confederacy of Native American communities scattered across the Northeast, and the sometimes uneasy relationship they have with the sport they invented. Lacrosse began as a rough-hewn contest played on stretches of open land with sticks made from hickory and catgut. It has increased greatly in popularity over the last two decades, with armies of high school and college players charging around manicured fields, dressed in bright uniforms and plastic helmets, their sticks bolstered with carbon fiber. The world championship attracts teams from around the globe. The Haudenosaunee (hoad-nah-SHAW-nee) have fought to keep pace with the times. Their homegrown squad, the Iroquois Nationals, draws from a small talent pool but usually ranks in the top five internationally. -

Indigenous Visioning Circle Resources

Indigenous Visioning Circle Resources Books** Bigelow, Bill and Bob Peterson, editors. (1998) Rethinking Columbus – The Next 500 Years . Milwaukee, WI: Rethinking Schools Brown, Dee. (1970) Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee – An Indian History of the American West . New York, NY: Henry Holt and Company Michael F. Brown. (2003) Who Owns Native Culture? Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press Deloria Jr, Vine. (1985) Behind the Trail of Broken Treaties – An Indian Declaration of Independence . Austin, TX: University of Texas Press Deloria Jr, Vine. (1969) Custer Died for Your Sins. New York, NY: Macmillan Publishing Company *Heinrichs, Steve, editor. (2013) Buffalo Shout, Salmon Cry. Waterloo, ON: Herald Press *King, Thomas. (2013) The Inconvenient Indian: A Curious Account of Native People in North America. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press LaDuke, Winona. (1999) All Our Relations – Native Struggles for Land and Life . Cambridge, MA: South End Press Mander, Jerry. (1991) In the Absence of the Sacred - The Failure of Technology & the Survival of the Indian Nations (Chapters 11 – 13 and Chapters 15 – 18). San Francisco, CA: Sierra Club Books McCaslin , Wanda D., editor. (2005) Justice as Healing: Indigenous Ways . St. Paul, MN: Living Justice Press Stannard, David E. (1992) American Holocaust – The Conquest of the New World. New York, NY: Oxford University Press Tinker, George E. (2008) American Indian Liberation: A Theology of Sovereignty. Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books Tinker, George E. (1993) Missionary Conquest – The Gospel and Native American Genocide. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press *study guide included/available **All books available from MCC Central States lending library: (316)-283-2720, [email protected] Online resources (search by title) Websites: Dismantling the Doctrine of Discovery - A movement of Anabaptist people of faith Website coordinating the efforts of the (Mennonite) Dismantling the Doctrine of Discovery Coalition – including video (see below), educational resources and timeline. -

Summit of the Elders Haudenosaunee Environmental Restoration

HflUDEHOSflUnEE EHUIRQnmEflTHL RESTORHTiOn An Indigenous Strategy for Human SustainabiHty Summit of the Elders Haudenosaunee Environmental Restoration Tuesday, July 18th 1995, Trusteeship Council, United Nations - New York Native Americans Respond to Rio Summit MEDIA KIT CONTENTS: • INFORMATION RELEASE • BACKGROUND - HAUDENOSAUNEE HISTORY • BACKGROUND - UNEP PARTNERS • UN AGENDA - JULY 18 INFORMATION RELEASE JULY 10, 1995 Cambridge/New York NATIVE AMERICANS RESPOND TO RIO SUMMIT Pollution has heavily impacted the Haudenosaunee people, who rely on their water and land resources for subsistence. After several months of intensive study and investigation, the leaders of the Haudenosaunee have produced a report on the source and nature of the hazards to which their communities are exposed, and have formulated an environmental restoration plan. Consisting of six historically linked nations: Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Seneca, Cayuga and Tuscarora, the Haudenosaunee were once a powerful group in northeast America, and their alliance was eagerly sought by the contending European colonial powers in America. The thirteen original colonies of the United States took many ideas on democracy from the Haudenosaunee, even using their concept of a confederacy as a model for the U.S. Constitution. The Haudenosaunee, also known as the Iroquois Six Nations Confederacy, are now working closely with the United Nations to review environmental pollution and mapping a strategy of environmental restoration. Their strategy constitutes one of the first indigenous responses to Chapter 26, Agenda 21 of the 1992 Rio Earth Summit and the International Decade of the World Indigenous People declared by the General Assembly of the United Nations in 1994. This document, prepared with the support of UNEP's partnership programme Indigenous Development International (INDI) at Cambridge University, represents the first comprehensive indigenous restoration strategy whereby the Haudenosaunee peoples have defined the problems they are confronting and recommended measures for their remediation. -

Echoes of the Earth in Times of Climate Change: Native American Artists’ and Culture Bearers’ Knowledge and Perspectives

A Working Guide to the Landscape of Arts for Change A collection of writings depicting the wide range of ways the arts make community, civic, and social change. Echoes of the Earth in Times of Climate Change: Native American Artists’ and Culture Bearers’ Knowledge and Perspectives By Edward Wemytewa Native American artists and culture bearers brought Indigenous perspectives and critical voices to pressing issues of the environment at the April 2012 conference, Echoes of the Earth in Times of Climate Change, sponsored by the Seventh Generation Fund and Hopa Mountain. Artist, writer, and activist Edward Wemytewa (Zuni) eloquently captures the perspectives of Native leaders and culture bearers as they look to their cultural heritage and wisdom— sacred ceremony, ancient languages, prophesy, and hallmarks of mutuality, reciprocity, and responsibility—for ways to regain the delicate ecological balance of the earth. A Working Guide to the Landscape of Arts for Change is supported by the Surdna Foundation as part of the Arts & Social Change Mapping Initiative supported by the Nathan Cummings Foundation, Open Society Foundations, CrossCurrents Foundation, Lambent Foundation, and Surdna Foundation. For more information, visit: www.artsusa.org/animatingdemocracy 2 INTRODUCTION The Echoes of the Earth conference held on April 6, 2012, at the Emerson Cultural Center in Bozeman, Montana was sponsored by the Seventh Generation Fund and Hopa Mountain. The intent of the conference was to raise consciousness about climate change by integrating Indigenous artists and culture bearers into the panel conversations to provide their perspectives on the subject, and accordingly to encourage conference participants in the deliberations. While this report will highlight the Indigenous voices presented at the conference, I think it is important to frame it within a “tribal cosmos.” I will use my Zuni cultural heritage to contextualize the conversation because the gathering only lasted one day and the presenters were, therefore, not able to elaborate further. -

Broken Chains of Custody: Possessing, Dispossessing, and Repossessing Lost Wampum Belts

Broken Chains of Custody: Possessing, Dispossessing, and Repossessing Lost Wampum Belts MARGARET M. BRUCHAC Assistant Professor of Anthropology Coordinator, Native American and Indigenous Studies University of Pennsylvania Introduction In the spring of 2009, two historical shell bead wampum belts1—iden- tified as “early” and “rare” and valued at between $15,000 and $30,000 each—were advertised for sale at a Sotheby’s auction of Amer- ican Indian art objects2 belonging to the estate of Herbert G. Welling- ton.3 One belt, identified as having been collected by Frank G. Speck from the Mohawk community in Oka (Kanesatake, Quebec) before 1929, was tagged with an old accession number from the Heye Foun- dation/Museum of the American Indian (MAI; MAI #16/3827). The second belt, collected by John Jay White from an unknown locale before 1926, was identified as Abenaki; it, too, was tagged with an old MAI number (MAI #11/123; Figure 1). The Sotheby’s notice caught the attention of the Haudenosaunee Standing Committee on Burial Rules and Regulations (HSC), a consor- tium of Six Nations Iroquoian chiefs, tribal historians, and community leaders who serve as advocates and watchdogs for tribal territory and 1 The generic term wampum, borrowed from the Algonquian word wampumpeag for “white shells” (Trumbull 1903, 340–41), refers to cylindrical marine shell beads used by the Indigenous peoples of northeastern North America. Algonquian is the broad linguistic clas- sification for the Algonkian cultural group that includes the Indigenous nations in New England and in parts of Quebec, Ontario, and the Great Lakes. The beads were carved from the shells of univalve and bivalve mollusks harvested from the shores of Long Island Sound and other northeastern North American locales where riverine fresh waters mingled with marine salt waters. -

LEGISLATIVE RESOLUTION Honoring Oren Lyons Upon the Occasion of His Designation As Recipient of the 2014 F.O.C.U.S

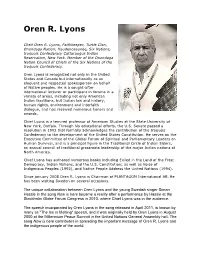

LEGISLATIVE RESOLUTION honoring Oren Lyons upon the occasion of his designation as recipient of the 2014 F.O.C.U.S. Wisdom Keeper Award on April 2, 2014 WHEREAS, It is the sense of this Legislative Body to recognize that the quality and character of life in the communities across New York State are reflective of the concerned and dedicated efforts of those individ- uals who devote themselves to the welfare of the community and its citi- zenry; and WHEREAS, Attendant to such concern, and in full accord with its long- standing traditions, this Legislative Body is justly proud to honor Oren Lyons upon the occasion of his designation as recipient of the 2014 F.O.C.U.S. Wisdom Keeper Award on Wednesday, April 2, 2014, at the Nicholas J. Pirro Convention Center at Oncenter, Syracuse, New York; and WHEREAS, The Wisdom Keeper Award recognizes community leaders who have enriched the community with their wisdom, perseverance and passion, and who honor and respect the teachings of the people of the Onondaga Nation; and WHEREAS, A man of singular distinction, Oren Lyons has continually demonstrated extreme competence, extraordinary intelligence, and dili- gent leadership in his unwavering service to the Syracuse community and subsequently has been selected for this most prestigious award; and WHEREAS, Oren Lyons, Faithkeeper of the Turtle Clan, Onondaga Nation Council of Chiefs, Haudenosaunee, has been called upon to contribute his time and talents to countless endeavors on behalf of F.O.C.U.S. and has always given of himself unstintingly; and WHEREAS, -

Join Us in Big Sky This September!

NEWSLETTER • SPRING 2017 CAIRHE CENTER FOR AMERICAN INDIAN AND RURAL HEALTH EQUITY JOIN US IN BIG SKY THIS SEPTEMBER! n this space in CAIRHE’s last • Presenting success stories in community-based health newsletter, I wrote that the research across Montana and beyond; health challenges in Montana • Teaching best practices in community-based Iare too pervasive for any one participatory research; and entity to address them alone. That • Giving researchers an insider’s view of successful grant being said, I added that CAIRHE proposals to the National Institutes of Health and other wants to be among the leaders in sponsoring agencies. a statewide effort toward positive It’s an ambitious agenda for an inaugural conference, but we feel change—“coordinating and sure that the Summit will forge new connections that will have a partnering with communities, other lasting impact on the health of Montana’s citizens. We hope you will researchers, and organizations of all help us spread the word and join us for a great event. For the latest types.” information on the program and conference registration, click here Alex Adams To that end, we’re proud to or simply Google “Montana Health Research Summit.” announce a landmark event coming this fall. Thanks for reading, and see you in Big Sky! CAIRHE and our colleagues at Montana INBRE will sponsor the Montana Health Research Summit on September 14-16 Alexandra Adams, M.D., Ph.D. in Big Sky, Mont. The Summit will bring together leading health Director and Principal Investigator researchers, public health professionals, and representatives from the state’s diverse tribal and rural communities to foster collaboration, enhance Montana’s health research capacity, and improve outcomes in the areas of health equity, environmental health, nutrition and food sovereignty, mental health, and infectious diseases. -

Oren R. Lyons

Oren R. Lyons Cheif Oren R. Lyons, Faithkeeper, Turtle Clan, Onondaga Nation, Haudenosaunee, Six Nations, Iroquois Confederacy Cattaraugus Indian Reservation, New York. Member of the Onondaga Nation Council of Chiefs of the Six Nations of the Iroquois Confederacy. Oren Lyons is recognized not only in the United States and Canada but internationally as an eloquent and respected spokesperson on behalf of Native peoples. He is a sought-after international lecturer or participant in forums in a variety of areas, including not only American Indian traditions, but Indian law and history, human rights, environment and interfaith dialogue, and has received numerous honors and awards. Chief Lyons is a tenured professor of American Studies at the State University of New York, Buffalo. Through his educational efforts, the U.S. Senate passed a resolution in 1992 that formally acknowledges the contribution of the Iroquois Confederacy to the development of the United States Constitution. He serves on the Executive Committee of the Global Forum of Spiritual and Parliamentary Leaders on Human Survival, and is a principal figure in the Traditional Circle of Indian Elders, an annual council of traditional grassroots leadership of the major Indian nations of North America. Chief Lyons has authored numerous books including Exiled in the Land of the Free; Democracy, Indian Nations, and the U.S. Constitution; as well as Voice of Indigenous Peoples (1992), and Native People Address the United Nations (1994). Since january 2008 Oren R. Lyons is Chairman of PLANTAGON International AB. He has been visiting Sweden on several occasions. The unique collaboration between Oren Lyons and the young Swedish singer Simon Hassle in the song Now is here became a reality after a performance by Hassle at the Stockholm Globe Forum Congress in 2010, where Chief Lyons was in the audience. -

Indigenous Visioning Circle Resources

Indigenous Visioning Circle Resources Books** Bigelow, Bill and Bob Peterson, editors. (1998) Rethinking Columbus – The Next 500 Years. Milwaukee, WI: Rethinking Schools Brown, Dee. (1970) Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee – An Indian History of the American West. New York, NY: Henry Holt and Company Michael F. Brown. (2003) Who Owns Native Culture? Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press Deloria Jr, Vine. (1985) Behind the Trail of Broken Treaties – An Indian Declaration of Independence. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press Deloria Jr, Vine. (1969) Custer Died for Your Sins. New York, NY: Macmillan Publishing Company *Heinrichs, Steve, editor. (2013) Buffalo Shout, Salmon Cry. Waterloo, ON: Herald Press *King, Thomas. (2013) The Inconvenient Indian: A Curious Account of Native People in North America. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press LaDuke, Winona. (1999) All Our Relations – Native Struggles for Land and Life. Cambridge, MA: South End Press Mander, Jerry. (1991) In the Absence of the Sacred ‐ The Failure of Technology & the Survival of the Indian Nations (Chapters 11 – 13 and Chapters 15 – 18). San Francisco, CA: Sierra Club Books McCaslin, Wanda D., editor. (2005) Justice as Healing: Indigenous Ways. St. Paul, MN: Living Justice Press Stannard, David E. (1992) American Holocaust – The Conquest of the New World. New York, NY: Oxford University Press Tinker, George E. (2008) American Indian Liberation: A Theology of Sovereignty. Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books Tinker, George E. (1993) Missionary Conquest – The Gospel and Native -

Amerind Quarterly

Amerind quarterly The Newsletter of the Amerind Foundation SPRING/SUMMER 2008 ( vol. 5, nos. 2 & 3) Amerind Studies in Archaeology The Amerind Foundation was established over 70 years ago to serve primarily as an archaeological research center. Major excavation projects were carried out by Amerind staff in Texas Canyon, near Gleeson, in the Winchester Mountains, at a half dozen sites in the San Pedro and Santa Cruz Valleys, in northern Chihuahua, southwestern New Mexico, and as far away as the Lukachukai Mountains in northeastern Arizona. These excavations brought tens of thousands of artifacts into Amerind’s collections and their results were documented in nearly twenty publications, many of which remain seminal references for archaeologists conducting research in the Southwest Borderlands. Since the death of Amerind’s long-time director Charles Di Peso in 1982, the Amerind has pursued a very different mission. We no longer conduct basic archaeological research (in archaeological parlance, we no longer dig square holes in the ground), but we are still deeply involved in research, now in a supporting role. Since 1988 the Amerind has sponsored nearly two dozen advanced seminars (in the last several years we’ve been averaging four to five seminars a year). Seminar participants are housed in the Fulton House and meet in Amerind’s research library, and the proceedings of the seminars are published in major academic presses (from 1988-2000, the University of New Mexico Press, and since 2001 through the University of Arizona Press). In 2006 we initiated a new publication series with the University of Arizona Press, entitled Amerind Studies in Archaeology, and the first title in the series came out in December 2007. -

LACROSSE: the Creator’S Game

ONONDAGA LAND RIGHTS & Our Common Future II A Collaborative Educational Series bringing together the Central New York community, Syracuse University, SUNY ESF, Le Moyne College, SUNY Empire State College, Onondaga Community College and seven other colleges LACROSSE: The Creator’s Game “When you talk about lacrosse, you talk about the lifeblood of the Six Nations. The game is ingrained into our culture our system and our lives.” – Onondaga Faithkeeper Oren Lyons, Jr. Oren Lyons is a Faithkeeper of the On- Roy Simmons Jr. has dedicated much ondaga Nation Turtle clan and has been a clear, of his life to the Syracuse University men’s lacrosse persistent and respected voice for the Onondaga, team as both player (1956-58) and coach (1971-1998). the Haudenosaunee and for Indigenous people During his time at Syracuse, Roy led the team to 16 throughout the world. He has been present at straight Final Fours and 6 NCAA national champi- many of the most significant events for Indigenous onships. In 2009 Roy was awarded the Tewaaraton people over the last four decades. Lyons was an All- Spirit Award which recognizes exemplary dedication American Lacrosse Goalie at SU in 1957 and 1958 to the sport of lacrosse as well as making a significant and serves as Honorary Chairman of the Iroquois contribution to society. National Lacrosse Team. Monday, April 5 at 7:00 pm Syracuse Stage, 820 East Genesee St., Syracuse Program is free and followed by a reception University Sponsors: SYRACUSE UNIVERSITY: Chancellor’s Office, Religion, Anthropology, Communication -

Doctrine of Discovery and Its Enduring Impact on Indigenous Peoples

The Doctrine of Discovery and its Enduring Impact on Indigenous Peoples WHAT IS THE DOCTRINE OF DISCOVERY? The Discovery Doctrine is a construct of public international law expounded by the United States Supreme Court in a series of decisions, initially in Johnson v. M’Intosh in 1823. It is based on a series of 15th century Papal Bulls that gave Christian explorers the right to claim title to the lands they “discovered” and lay claim to those lands for their Christian Monarchs. Any land that was not inhabited by Christians was available to be “discovered”, claimed, and exploited. If the “pagan” inhabitants could be converted, they might be spared. If not, they could be enslaved or killed. “By this directive, by fiat, the European nations claimed for themselves the entire Western Hemisphere. It is a demonstration of the incredible arrogance of the time. This has resulted in the subjugation, genocide, relegating indigenous peoples to a subhuman status in international politics. Indigenous peoples have been laboring and suffering under that status right up until the U.N. Declaration on the Rights of Indig- enous Peoples was established in 2007, which for the first time recognized Indigenous peoples as ‘peoples’. Up until recently, we were politically denied human rights.” - Onondaga Nation Faithkeeper Oren Lyons THE DOCTRINE OF DISCOVERY IS STILL USED TO DENY INDIGENOUS LAND RIGHTS “Under the ‘Doctrine of Discovery’ ... fee title to the lands occupied by Indians when the colonists arrived became vested in the sovereign — first the discovering European nation and later the original states and the United States” - Footnote #1, City of Sherrill v.