The Sublime Network; Painterly Passage and Materiality in the Post Internet Era

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Philosophy in the Artworld: Some Recent Theories of Contemporary Art

philosophies Article Philosophy in the Artworld: Some Recent Theories of Contemporary Art Terry Smith Department of the History of Art and Architecture, the University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA 15213, USA; [email protected] Received: 17 June 2019; Accepted: 8 July 2019; Published: 12 July 2019 Abstract: “The contemporary” is a phrase in frequent use in artworld discourse as a placeholder term for broader, world-picturing concepts such as “the contemporary condition” or “contemporaneity”. Brief references to key texts by philosophers such as Giorgio Agamben, Jacques Rancière, and Peter Osborne often tend to suffice as indicating the outer limits of theoretical discussion. In an attempt to add some depth to the discourse, this paper outlines my approach to these questions, then explores in some detail what these three theorists have had to say in recent years about contemporaneity in general and contemporary art in particular, and about the links between both. It also examines key essays by Jean-Luc Nancy, Néstor García Canclini, as well as the artist-theorist Jean-Phillipe Antoine, each of whom have contributed significantly to these debates. The analysis moves from Agamben’s poetic evocation of “contemporariness” as a Nietzschean experience of “untimeliness” in relation to one’s times, through Nancy’s emphasis on art’s constant recursion to its origins, Rancière’s attribution of dissensus to the current regime of art, Osborne’s insistence on contemporary art’s “post-conceptual” character, to Canclini’s preference for a “post-autonomous” art, which captures the world at the point of its coming into being. I conclude by echoing Antoine’s call for artists and others to think historically, to “knit together a specific variety of times”, a task that is especially pressing when presentist immanence strives to encompasses everything. -

Tate Report 08-09

Tate Report 08–09 Report Tate Tate Report 08–09 It is the Itexceptional is the exceptional generosity generosity and and If you wouldIf you like would to find like toout find more out about more about PublishedPublished 2009 by 2009 by vision ofvision individuals, of individuals, corporations, corporations, how youhow can youbecome can becomeinvolved involved and help and help order of orderthe Tate of the Trustees Tate Trustees by Tate by Tate numerousnumerous private foundationsprivate foundations support supportTate, please Tate, contact please contactus at: us at: Publishing,Publishing, a division a divisionof Tate Enterprisesof Tate Enterprises and public-sectorand public-sector bodies that bodies has that has Ltd, Millbank,Ltd, Millbank, London LondonSW1P 4RG SW1P 4RG helped Tatehelped to becomeTate to becomewhat it iswhat it is DevelopmentDevelopment Office Office www.tate.org.uk/publishingwww.tate.org.uk/publishing today andtoday enabled and enabled us to: us to: Tate Tate MillbankMillbank © Tate 2009© Tate 2009 Offer innovative,Offer innovative, landmark landmark exhibitions exhibitions London LondonSW1P 4RG SW1P 4RG ISBN 978ISBN 1 85437 978 1916 85437 0 916 0 and Collectionand Collection displays displays Tel 020 7887Tel 020 4900 7887 4900 A catalogue record for this book is Fax 020 Fax7887 020 8738 7887 8738 A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. DevelopDevelop imaginative imaginative education education and and available from the British Library. interpretationinterpretation programmes programmes AmericanAmerican Patrons Patronsof Tate of Tate Every effortEvery has effort been has made been to made locate to the locate the 520 West520 27 West Street 27 Unit Street 404 Unit 404 copyrightcopyright owners ownersof images of includedimages included in in StrengthenStrengthen and extend and theextend range the of range our of our New York,New NY York, 10001 NY 10001 this reportthis and report to meet and totheir meet requirements. -

Film and Media As a Site for Memory in Contemporary Art Domingo Martinez Rosario Universidad Nebrija (Madrid, Spain) E-Mail: [email protected]

ACTA UNIV. SAPIENTIAE, FILM AND MEDIA STUDIES, 14 (2017) 157–173 DOI: 10.1515/ausfm-2017-0007 Film and Media as a Site for Memory in Contemporary Art Domingo Martinez Rosario Universidad Nebrija (Madrid, Spain) E-mail: [email protected] Abstract. This article explores the relationship between film, contemporary art and cultural memory. It aims to set out an overview of the use of film and media in artworks dealing with memory, history and the past. In recent decades, film and media projections have become some of the most common mediums employed in art installations, multi-screen artworks, sculptures, multi-media art, as well as many other forms of contemporary art. In order to examine the links between film, contemporary art and memory, I will firstly take a brief look at cultural memory and, secondly, I will set out an overview of some pieces of art that utilize film and video to elucidate historical and mnemonic accounts. Thirdly, I will consider the specific features and challenges of film and media that make them an effective repository in art to represent memory. I will consider the work of artists like Tacita Dean, Krzysztof Wodiczko and Jane and Louise Wilson, whose art is heavily influenced and inspired by concepts of memory, history, nostalgia and melancholy. These artists provide examples of the use of film in art, and they have established contemporary art as a site for memory. Keywords: contemporary art, cultural memory, memory, film, temporality. Introduction Film and video have become two of the most common disciplines of contemporary art in recent decades. -

PRESS RELEASE Wednesday 22 January UNDER EMBARGO Until 10.30 on 22.1.20

PRESS RELEASE Wednesday 22 January UNDER EMBARGO until 10.30 on 22.1.20 Artists launch Art Fund campaign to save Prospect Cottage, Derek Jarman’s home & garden, for the nation – Art Fund launches £3.5 million public appeal to save famous filmmaker’s home – National Heritage Memorial Fund, Art Fund and Linbury Trust give major grants in support of innovative partnership with Tate and Creative Folkestone – Leading artists Tilda Swinton, Tacita Dean, Jeremy Deller, Michael Craig-Martin, Isaac Julien, Howard Sooley, and Wolfgang Tillmans give everyone the chance to own art in return for donations through crowdfunding initiative www.artfund.org/prospect Derek Jarman at Prospect Cottage. Photo: © Howard Sooley Today, Art Fund director Stephen Deuchar announced the launch of Art Fund’s £3.5 million public appeal to save and preserve Prospect Cottage in Dungeness, Kent, the home and garden of visionary filmmaker, artist and activist, Derek Jarman, for the nation. Twitter Facebook artfund.org @artfund theartfund National Art Collections Fund. A charity registered in England and Wales 209174, Scotland SC038331 Art Fund needs to raise £3.5m by 31 March 2020 to purchase Prospect Cottage and to establish a permanently funded programme to conserve and maintain the building, its contents and its garden for the future. Major grants from the National Heritage Memorial Fund, Art Fund, the Linbury Trust, and private donations have already taken the campaign half way towards its target. Art Fund is now calling on the public to make donations of all sizes to raise the funds still needed. Through an innovative partnership between Art Fund, Creative Folkestone and Tate, the success of this campaign will enable continued free public access to the cottage’s internationally celebrated garden, the launch of artist residencies, and guided public visits within the cottage itself. -

Postinternet, Its Art and (The) New Aesthetic

POSTINTERNET, ITS ART AND (THE) NEW AESTHETIC — A Conceptual Framework for Art Education POSTINTERNET, ITS ART AND (THE) NEW AESTHETIC — A Conceptual Framework for Art Education Elina Nissinen Master of Arts thesis, 30 ECTS Supervisor Kevin Tavin Master’s Program in Art Education Department of Art Aalto University School of Arts, Design and Architecture 2018 Author Elina Nissinen Työn nimi Postinternet, Its Art and (The) New Aesthetic – A Conceptual Framework for Art Education Department Department of Art Degree programme Master’s program in Art Education Year 2018 Number of pages 83 Language English Abstract As one might expect from terms employing the prefixes ‘post’ or ‘new,’ combined with the words ‘internet,’ ‘art,’ and ‘aesthetic,’ postinternet, postinternet art (PIA), and New Aesthetic ((the) NA) are broad and disputable concepts. I started this study because I noticed that these ambiguous, yet widely- discussed terms were hardly acknowledged in art education. This thesis provides a conceptual framework for postinternet, PIA, and (the) (the) NA through a critical review of the literature. Postinternet and (the) NA are notions and phenomena that signpost an era and a condition of unprecedented pace of computation-driven transformations in the human culture. They continue the list of theoretical neologisms indicating the changes brought about by the post-conditions. This thesis establishes that postinternet, PIA, and (the) NA are characterized through their paradoxical relation to time and temporality at conceptual and thematical levels. Obsessed with novelty, these terms attempt to break off from their “previous,” while, starting from their titles, simultaneously anchoring themselves to the past. Postinternet is a notion that describes the inescapable consequences of the intermixing of the online and offline, the omnipresence of the internet. -

This Book Is a Compendium of New Wave Posters. It Is Organized Around the Designers (At Last!)

“This book is a compendium of new wave posters. It is organized around the designers (at last!). It emphasizes the key contribution of Eastern Europe as well as Western Europe, and beyond. And it is a very timely volume, assembled with R|A|P’s usual flair, style and understanding.” –CHRISTOPHER FRAYLING, FROM THE INTRODUCTION 2 artbook.com French New Wave A Revolution in Design Edited by Tony Nourmand. Introduction by Christopher Frayling. The French New Wave of the 1950s and 1960s is one of the most important movements in the history of film. Its fresh energy and vision changed the cinematic landscape, and its style has had a seminal impact on pop culture. The poster artists tasked with selling these Nouvelle Vague films to the masses—in France and internationally—helped to create this style, and in so doing found themselves at the forefront of a revolution in art, graphic design and photography. French New Wave: A Revolution in Design celebrates explosive and groundbreaking poster art that accompanied French New Wave films like The 400 Blows (1959), Jules and Jim (1962) and The Umbrellas of Cherbourg (1964). Featuring posters from over 20 countries, the imagery is accompanied by biographies on more than 100 artists, photographers and designers involved—the first time many of those responsible for promoting and portraying this movement have been properly recognized. This publication spotlights the poster designers who worked alongside directors, cinematographers and actors to define the look of the French New Wave. Artists presented in this volume include Jean-Michel Folon, Boris Grinsson, Waldemar Świerzy, Christian Broutin, Tomasz Rumiński, Hans Hillman, Georges Allard, René Ferracci, Bruno Rehak, Zdeněk Ziegler, Miroslav Vystrcil, Peter Strausfeld, Maciej Hibner, Andrzej Krajewski, Maciej Zbikowski, Josef Vylet’al, Sandro Simeoni, Averardo Ciriello, Marcello Colizzi and many more. -

A Critical Analysis of Art in the Post- Internet Era Mark Gens

Art Post Internet A Critical Analysis of Art in the Post- Internet Era Mark Gens Te ability of technology to transform art, artist, and art world is not a new concept. Te impact of digital technology and the Internet is yet another dynamic force. What is taking place is a redefnition of authorship, collaboration, and materiality as well as a need for new theoretical and aesthetic notions of how – and where – art is made, viewed, marketed and collected. Tese factors, the ever-expanding World Wide Web, and the pervasive individual ownership of networked devices by most of the privileged world, have ushered in what some refer to as the Post-Internet era. Rather than focusing on the validity of the highly-debated term “Post-Internet” this paper will focus on the developmental shift to which the term refers. Tis shift is an important marker in the movement of ideas and criticality, culture, and context. It is necessary to consider the digital art predecessors to the Post-Internet era. However, the exhibition Art Post-Internet, held at the Ullens Center for Contemporary Art in Beijing, China in the spring of 2014, is vital for its well-articulated curatorial perspective. Although the signifcance of the Post-Internet era is still being determined and defned at this moment, Art Post-Internet has made great strides in solidifying its look, methods, context and meaning. Post-Internet is not the end of an era, but rather a poignant marker with lasting potential in the continuum of art history. Mark Gens is a multi-media artist, student, and writer in New York City. -

Mediating Internet Art Curatorial Modes in Tangible and Virtual Domains

MEDIATING INTERNET ART CURATORIAL MODES IN TANGIBLE AND VIRTUAL DOMAINS Jonathon Austin Lourenço Pereira Dissertação de Mestrado em Estudos Artísticos apresentada à Faculdade de Belas Artes da Universidade do Porto Orientadora: Profª. Doutora Catarina Carneiro de Sousa Porto, 2018 MEDIATING INTERNET ART CURATORIAL MODES IN TANGIBLE AND VIRTUAL DOMAINS by Jonathon Austin Lourenço Pereira A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Art Studies at the Faculty of Fine Arts of the University of Porto Supervised by Catarina Carneiro de Sousa Porto, 2018 ABSTRACT This dissertation examines Internet Art and its mediation efforts. As a practice with now more than 20 years of existence, Internet Art is still greatly marginalized from art institutional settings for its inferior status in comparison with tangible auratic artworks. The curatorial field of knowledge has been hardly handling the discussion of how technology has been transforming modes of production and mediation of art. The central aim here is to understand how Internet Art has been and can be mediated in online and tangible settings. The Literature Review has surveyed a broad range of writings about New Media Art and Internet Art in combination with direct engagement with artworks. This had the purpose of gaining insight into what Internet Art consists in, its behaviors and construction. To explore how Internet Art has been exhibited, preserved, and distributed, the research followed a multiple case studies method. It delved into five cases of mediation efforts related to Internet Art in both online and tangible settings. These have been surveyed qualitatively based on direct observation and engagement and secondary sources, such as exhibition reviews, curator statements, and audience input. -

Art As Communication: Y the Impact of Art As a Catalyst for Social Change Cm

capa e contra capa.pdf 1 03/06/2019 10:57:34 POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE OF LISBON . PORTUGAL C M ART AS COMMUNICATION: Y THE IMPACT OF ART AS A CATALYST FOR SOCIAL CHANGE CM MY CY CMY K Fifteenth International Conference on The Arts in Society Against the Grain: Arts and the Crisis of Democracy NUI Galway Galway, Ireland 24–26 June 2020 Call for Papers We invite proposals for paper presentations, workshops/interactive sessions, posters/exhibits, colloquia, creative practice showcases, virtual posters, or virtual lightning talks. Returning Member Registration We are pleased to oer a Returning Member Registration Discount to delegates who have attended The Arts in Society Conference in the past. Returning research network members receive a discount o the full conference registration rate. ArtsInSociety.com/2020-Conference Conference Partner Fourteenth International Conference on The Arts in Society “Art as Communication: The Impact of Art as a Catalyst for Social Change” 19–21 June 2019 | Polytechnic Institute of Lisbon | Lisbon, Portugal www.artsinsociety.com www.facebook.com/ArtsInSociety @artsinsociety | #ICAIS19 Fourteenth International Conference on the Arts in Society www.artsinsociety.com First published in 2019 in Champaign, Illinois, USA by Common Ground Research Networks, NFP www.cgnetworks.org © 2019 Common Ground Research Networks All rights reserved. Apart from fair dealing for the purpose of study, research, criticism or review as permitted under the applicable copyright legislation, no part of this work may be reproduced by any process without written permission from the publisher. For permissions and other inquiries, please visit the CGScholar Knowledge Base (https://cgscholar.com/cg_support/en). -

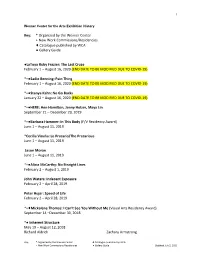

Key: * Organized by the Wexner Center + New Work Commissions/Residencies ♦ Catalogue Published by WCA ● Gallery Guide

1 Wexner Center for the Arts Exhibition History Key: * Organized by the Wexner Center + New Work Commissions/Residencies ♦ Catalogue published by WCA ● Gallery Guide ●LaToya Ruby Frazier: The Last Cruze February 1 – August 16, 2020 (END DATE TO BE MODIFIED DUE TO COVID-19) *+●Sadie Benning: Pain Thing February 1 – August 16, 2020 (END DATE TO BE MODIFIED DUE TO COVID-19) *+●Stanya Kahn: No Go Backs January 22 – August 16, 2020 (END DATE TO BE MODIFIED DUE TO COVID-19) *+●HERE: Ann Hamilton, Jenny Holzer, Maya Lin September 21 – December 29, 2019 *+●Barbara Hammer: In This Body (F/V Residency Award) June 1 – August 11, 2019 *Cecilia Vicuña: Lo Precario/The Precarious June 1 – August 11, 2019 Jason Moran June 1 – August 11, 2019 *+●Alicia McCarthy: No Straight Lines February 2 – August 1, 2019 John Waters: Indecent Exposure February 2 – April 28, 2019 Peter Hujar: Speed of Life February 2 – April 28, 2019 *+♦Mickalene Thomas: I Can’t See You Without Me (Visual Arts Residency Award) September 14 –December 30, 2018 *● Inherent Structure May 19 – August 12, 2018 Richard Aldrich Zachary Armstrong Key: * Organized by the Wexner Center ♦ Catalogue published by WCA + New Work Commissions/Residencies ● Gallery Guide Updated July 2, 2020 2 Kevin Beasley Sam Moyer Sam Gilliam Angel Otero Channing Hansen Laura Owens Arturo Herrera Ruth Root Eric N. Mack Thomas Scheibitz Rebecca Morris Amy Sillman Carrie Moyer Stanley Whitney *+●Anita Witek: Clip February 3-May 6, 2018 *●William Kentridge: The Refusal of Time February 3-April 15, 2018 All of Everything: Todd Oldham Fashion February 3-April 15, 2018 Cindy Sherman: Imitation of Life September 16-December 31, 2017 *+●Gray Matters May 20, 2017–July 30 2017 Tauba Auerbach Cristina Iglesias Erin Shirreff Carol Bove Jennie C. -

Thecollective

WORKPLACEGATESHEAD The Old Post Office 19-21 West Street Gateshead, NE8 1AD thecollective Preview: Friday 5th May 6pm – 8pm Exhibition continues: 6th May – 3rd June Opening hours: Tuesday – Saturday 11am – 5pm Issued Wednesday 26th April 2018 Workplace Gateshead is delighted to present the first public exhibition of selected works from The Founding Collective. FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Started in 2002 in London by a group of art professionals and families interested in living with contemporary art The Collective is a growing network of groups collecting, sharing and enjoying contemporary art in their homes or places of work. The combined collection of The Founding Group now comprises over 60 original and limited edition works by emerging and established artists. Selected by Workplace this exhibition includes works by: Mel Brimfield, Jemima Brown, Fiona Banner, Libia Castro & Olafur Olafsson, Martin Creed, Tom Dale, Michael Dean, Tacita Dean, Peter Doig, Bobby Dowler, Tracey Emin, Erica Eyres, Rose Finn-Kelcey, Ceal Floyer, Matthew Higgs, Gareth Jones, Alex Katz, Scott King, Jochen Klein, Edwin Li, Hilary Lloyd, Paul McCarthy, Paul Noble, Chris Ofili, Peter Pommerer, James Pyman, Frances Richardson, Giorgio Sadotti, Jane Simpson, Wolfgang Tillmans, Piotr Uklanski, Mark Wallinger, Bedwyr Williams, and Elizabeth Wright. Free public event: Friday 5th May, 5pm - 6pm, all welcome Founding members of The Collective will give an informal introduction to the history of the group, how it works, how it expanded and plans for the future. This will be followed by an open discussion chaired by WORKPLACE directors Paul Moss and Miles Thurlow focusing on the importance of collecting contemporary art, how to make a start regardless of budget, and the challenges and opportunities for new collectors in the North of England. -

Laughing at Our Inadequacies: Contemporary Cartoonish Painting, Internet Culture and the Tragicomic Character

Laughing at Our Inadequacies: Contemporary Cartoonish Painting, Internet Culture and the Tragicomic Character Amber Boardman A thesis in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Art and Design Faculty of Art and Design October 2018 Thesis/Dissertation Sheet Surname Boardman Given Name Amber Degree PhD Faculty Art and Design School Art and Design Thesis Title Laughing at Our Inadequacies: Contemporary Cartoonish Painting, Internet Culture and the Tragicomic Character Abstract This practice-based project examines ‘cartoonish painting’, an emerging trend of contemporary figurative painting which draws on links between cartoons, humour, narrative, character and bodily transformation. In my practice, cartoonish painting depicts and comments on the endless desire to transform body and self as promoted by Internet culture and social media. This thesis argues that the social media driven desire for self-improvement—bodily alteration and transformations of the self—creates a tragicomic effect that unfolds through the devices of narrative and character. I examine the still influential, Romantic theory of character developed by William James. James articulated well-rounded characters evolve over time through a series of identifications with external others. This thesis proposes that James’s formulations about character retain currency, as people identify with depictions of idealised bodies, high-performing and socially sanctioned selves disseminated through the Internet. This thesis argues, however, that this aspirational selfhood and identifying with idealised others creates feelings of inadequacy. The ideology of a striving, perfected self in search of the ‘American Dream’ will be analysed through Henri Bergson’s theory of the comic. Bergson argued that the failure of machine-like pursuits uncontrolled by consciousness can be manifested through comic depictions of the human body.