Downloaded on 2017-02-12T09:34:40Z

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Philosophy in the Artworld: Some Recent Theories of Contemporary Art

philosophies Article Philosophy in the Artworld: Some Recent Theories of Contemporary Art Terry Smith Department of the History of Art and Architecture, the University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA 15213, USA; [email protected] Received: 17 June 2019; Accepted: 8 July 2019; Published: 12 July 2019 Abstract: “The contemporary” is a phrase in frequent use in artworld discourse as a placeholder term for broader, world-picturing concepts such as “the contemporary condition” or “contemporaneity”. Brief references to key texts by philosophers such as Giorgio Agamben, Jacques Rancière, and Peter Osborne often tend to suffice as indicating the outer limits of theoretical discussion. In an attempt to add some depth to the discourse, this paper outlines my approach to these questions, then explores in some detail what these three theorists have had to say in recent years about contemporaneity in general and contemporary art in particular, and about the links between both. It also examines key essays by Jean-Luc Nancy, Néstor García Canclini, as well as the artist-theorist Jean-Phillipe Antoine, each of whom have contributed significantly to these debates. The analysis moves from Agamben’s poetic evocation of “contemporariness” as a Nietzschean experience of “untimeliness” in relation to one’s times, through Nancy’s emphasis on art’s constant recursion to its origins, Rancière’s attribution of dissensus to the current regime of art, Osborne’s insistence on contemporary art’s “post-conceptual” character, to Canclini’s preference for a “post-autonomous” art, which captures the world at the point of its coming into being. I conclude by echoing Antoine’s call for artists and others to think historically, to “knit together a specific variety of times”, a task that is especially pressing when presentist immanence strives to encompasses everything. -

Tate Report 08-09

Tate Report 08–09 Report Tate Tate Report 08–09 It is the Itexceptional is the exceptional generosity generosity and and If you wouldIf you like would to find like toout find more out about more about PublishedPublished 2009 by 2009 by vision ofvision individuals, of individuals, corporations, corporations, how youhow can youbecome can becomeinvolved involved and help and help order of orderthe Tate of the Trustees Tate Trustees by Tate by Tate numerousnumerous private foundationsprivate foundations support supportTate, please Tate, contact please contactus at: us at: Publishing,Publishing, a division a divisionof Tate Enterprisesof Tate Enterprises and public-sectorand public-sector bodies that bodies has that has Ltd, Millbank,Ltd, Millbank, London LondonSW1P 4RG SW1P 4RG helped Tatehelped to becomeTate to becomewhat it iswhat it is DevelopmentDevelopment Office Office www.tate.org.uk/publishingwww.tate.org.uk/publishing today andtoday enabled and enabled us to: us to: Tate Tate MillbankMillbank © Tate 2009© Tate 2009 Offer innovative,Offer innovative, landmark landmark exhibitions exhibitions London LondonSW1P 4RG SW1P 4RG ISBN 978ISBN 1 85437 978 1916 85437 0 916 0 and Collectionand Collection displays displays Tel 020 7887Tel 020 4900 7887 4900 A catalogue record for this book is Fax 020 Fax7887 020 8738 7887 8738 A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. DevelopDevelop imaginative imaginative education education and and available from the British Library. interpretationinterpretation programmes programmes AmericanAmerican Patrons Patronsof Tate of Tate Every effortEvery has effort been has made been to made locate to the locate the 520 West520 27 West Street 27 Unit Street 404 Unit 404 copyrightcopyright owners ownersof images of includedimages included in in StrengthenStrengthen and extend and theextend range the of range our of our New York,New NY York, 10001 NY 10001 this reportthis and report to meet and totheir meet requirements. -

Arts Celebrations Like Russian State Library, with the First Inventory the Edinburgh- Festival and Exhibitions Like in 20 Years Being- Checked

which established a fund for U.S. artists at Lost: Many manuscripts are missing from the NEWS & NOTES visual and performing arts celebrations like Russian State Library, with the first inventory the Edinburgh- Festival and exhibitions like in 20 years being- checked. 258 missing., the Venice Biennale, is no more. The private manuscripts are stolen or misplaced. &onNews sector must now be relied upon for continued Christie's & Sotheby's in May sold a rare support for the Venice Biennale and other lo& Footnotes in academic writing have Vincent Van Gogh cafe scene at $10.3 mil- events."The Government's budget in this area gone the way of all texts. Footnotes have cer- lion at Christie's. Sotheby's sold Claude cannot be sustained at cold war levels,"said tainly declined in the book publishing indus- Monet's "Les Meules, Giverny, Effet du Joseph Durn, director of the U.S.I.A. try. Footnotes started in the 17th century, the Matin", an early work, to a Japanese dealer longest of which ran for 165 pages in 1840. for $7.15 million. Asian bidders are back. : Archeologists have uncovered three clay tablets inscribed more than 3,200 years MUSEUM NEWS & WUND LOST ago that may have been part of the royal ar- Tbe Metropolitan Museum of Art in New Founl: Washington art collector and historian chives of the largest city-state in the ancient York City has been given 13 works of 20th Thurlow Evans Tibbs Jr. is donating the best region of Canaan. The tablets date to 1550 - century art by such masters as Picasso, of his collection of 19th and 20th century art- 1200 B.C. -

Shock Value: the COLLECTOR AS PROVOCATEUR?

Shock Value: THE COLLECTOR AS PROVOCATEUR? BY REENA JANA SHOCK VALUE: enough to prompt San Francisco Chronicle art critic Kenneth Baker to state, “I THE COLLECTOR AS PROVOCATEUR? don’t know another private collection as heavy on ‘shock art’ as Logan’s is.” When asked why his tastes veer toward the blatantly gory or overtly sexual, Logan doesn’t attempt to deny that he’s interested in shock art. But he does use predictably general terms to “defend” his collection, as if aware that such a collecting strategy may need a defense. “I have always sought out art that faces contemporary issues,” he says. “The nature of contemporary art is that it isn’t necessarily pretty.” In other words, collecting habits like Logan’s reflect the old idea of le bourgeoisie needing a little épatement. Logan likes to draw a line between his tastes and what he believes are those of the status quo. “The majority of people in general like to see pretty things when they think of what art should be. But I believe there is a better dialogue when work is unpretty,” he says. “To my mind, art doesn’t fulfill its function unless there’s ent Logan is burly, clean-cut a dialogue started.” 82 and grey-haired—the farthestK thing you could imagine from a gold-chain- Indeed, if shock art can be defined, it’s art that produces a visceral, 83 wearing sleazeball or a death-obsessed goth. In fact, the 57-year-old usually often unpleasant, reaction, a reaction that prompts people to talk, even if at sports a preppy coat and tie. -

Free | Anno Nono | Numero Sessantotto | Settembre-Ottobre Duemiladieci | L’Idea Era Un’Altra, Per Questo Editoriale

Mensile - Sped. in A.P. 45% art. 2. c. 20 let. B - l. 662/96 Firenze Copia euro 0,0001 20 c. 2. art. 45% A.P. in Sped. - Mensile free | anno nono | numero sessantotto | settembre-ottobre duemiladieci | www.exibart.com L’idea era un’altra, per questo editoriale. Il proposito iniziale, di fine estate, era di imbastire una riflessioncina sui tagli alla cultura. Riflessione che sarebbe stata super-pop, iper-qualunquista, basica, basica, basica. Ehggià, perché se una fazione – quella attualmente al potere - che deve le sue fortune economiche e politiche al mezzo televisivo decide di tagliare di brutto teatri, cinema ed esposizioni d’arte, secondo noi è davvero ridicolo sorprendersi. Sarà un discorso da bar, sarà un discorso da autobus, sarà un discorso da supermercato, ma non è semplicemente ovvio che chi tanto più è ricco quanta più gente vede la tv, punti a evitare il più possibile che il pubblico potenziale venga distratto da opere liriche, rappresentazioni, cultura e mostre d’arte? Che il governo si comporti in questo modo è di una coerenza lineare: non merita neppure commento. Ecco perché abbiamo deciso di cambiare argomento per iniziare la stagione. E di passare a qualcosa di decisamente più positivo. Positivo come può esserlo soltanto l’accorgersi che il proprio Paese, nelle sue infrastrutture creative e di qualità, riesce nonostante tutto (e nonostante i tagli, raccordandosi al discorso di cui sopra) a far bella mostra di sé anche all’estero. Se non addirittura a spadroneggiare giocando su diversi fronti, come sta succedendo in questi mesi a New York. -

Film and Media As a Site for Memory in Contemporary Art Domingo Martinez Rosario Universidad Nebrija (Madrid, Spain) E-Mail: [email protected]

ACTA UNIV. SAPIENTIAE, FILM AND MEDIA STUDIES, 14 (2017) 157–173 DOI: 10.1515/ausfm-2017-0007 Film and Media as a Site for Memory in Contemporary Art Domingo Martinez Rosario Universidad Nebrija (Madrid, Spain) E-mail: [email protected] Abstract. This article explores the relationship between film, contemporary art and cultural memory. It aims to set out an overview of the use of film and media in artworks dealing with memory, history and the past. In recent decades, film and media projections have become some of the most common mediums employed in art installations, multi-screen artworks, sculptures, multi-media art, as well as many other forms of contemporary art. In order to examine the links between film, contemporary art and memory, I will firstly take a brief look at cultural memory and, secondly, I will set out an overview of some pieces of art that utilize film and video to elucidate historical and mnemonic accounts. Thirdly, I will consider the specific features and challenges of film and media that make them an effective repository in art to represent memory. I will consider the work of artists like Tacita Dean, Krzysztof Wodiczko and Jane and Louise Wilson, whose art is heavily influenced and inspired by concepts of memory, history, nostalgia and melancholy. These artists provide examples of the use of film in art, and they have established contemporary art as a site for memory. Keywords: contemporary art, cultural memory, memory, film, temporality. Introduction Film and video have become two of the most common disciplines of contemporary art in recent decades. -

PRESS RELEASE Wednesday 22 January UNDER EMBARGO Until 10.30 on 22.1.20

PRESS RELEASE Wednesday 22 January UNDER EMBARGO until 10.30 on 22.1.20 Artists launch Art Fund campaign to save Prospect Cottage, Derek Jarman’s home & garden, for the nation – Art Fund launches £3.5 million public appeal to save famous filmmaker’s home – National Heritage Memorial Fund, Art Fund and Linbury Trust give major grants in support of innovative partnership with Tate and Creative Folkestone – Leading artists Tilda Swinton, Tacita Dean, Jeremy Deller, Michael Craig-Martin, Isaac Julien, Howard Sooley, and Wolfgang Tillmans give everyone the chance to own art in return for donations through crowdfunding initiative www.artfund.org/prospect Derek Jarman at Prospect Cottage. Photo: © Howard Sooley Today, Art Fund director Stephen Deuchar announced the launch of Art Fund’s £3.5 million public appeal to save and preserve Prospect Cottage in Dungeness, Kent, the home and garden of visionary filmmaker, artist and activist, Derek Jarman, for the nation. Twitter Facebook artfund.org @artfund theartfund National Art Collections Fund. A charity registered in England and Wales 209174, Scotland SC038331 Art Fund needs to raise £3.5m by 31 March 2020 to purchase Prospect Cottage and to establish a permanently funded programme to conserve and maintain the building, its contents and its garden for the future. Major grants from the National Heritage Memorial Fund, Art Fund, the Linbury Trust, and private donations have already taken the campaign half way towards its target. Art Fund is now calling on the public to make donations of all sizes to raise the funds still needed. Through an innovative partnership between Art Fund, Creative Folkestone and Tate, the success of this campaign will enable continued free public access to the cottage’s internationally celebrated garden, the launch of artist residencies, and guided public visits within the cottage itself. -

This Book Is a Compendium of New Wave Posters. It Is Organized Around the Designers (At Last!)

“This book is a compendium of new wave posters. It is organized around the designers (at last!). It emphasizes the key contribution of Eastern Europe as well as Western Europe, and beyond. And it is a very timely volume, assembled with R|A|P’s usual flair, style and understanding.” –CHRISTOPHER FRAYLING, FROM THE INTRODUCTION 2 artbook.com French New Wave A Revolution in Design Edited by Tony Nourmand. Introduction by Christopher Frayling. The French New Wave of the 1950s and 1960s is one of the most important movements in the history of film. Its fresh energy and vision changed the cinematic landscape, and its style has had a seminal impact on pop culture. The poster artists tasked with selling these Nouvelle Vague films to the masses—in France and internationally—helped to create this style, and in so doing found themselves at the forefront of a revolution in art, graphic design and photography. French New Wave: A Revolution in Design celebrates explosive and groundbreaking poster art that accompanied French New Wave films like The 400 Blows (1959), Jules and Jim (1962) and The Umbrellas of Cherbourg (1964). Featuring posters from over 20 countries, the imagery is accompanied by biographies on more than 100 artists, photographers and designers involved—the first time many of those responsible for promoting and portraying this movement have been properly recognized. This publication spotlights the poster designers who worked alongside directors, cinematographers and actors to define the look of the French New Wave. Artists presented in this volume include Jean-Michel Folon, Boris Grinsson, Waldemar Świerzy, Christian Broutin, Tomasz Rumiński, Hans Hillman, Georges Allard, René Ferracci, Bruno Rehak, Zdeněk Ziegler, Miroslav Vystrcil, Peter Strausfeld, Maciej Hibner, Andrzej Krajewski, Maciej Zbikowski, Josef Vylet’al, Sandro Simeoni, Averardo Ciriello, Marcello Colizzi and many more. -

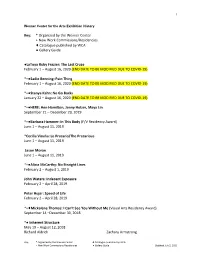

Key: * Organized by the Wexner Center + New Work Commissions/Residencies ♦ Catalogue Published by WCA ● Gallery Guide

1 Wexner Center for the Arts Exhibition History Key: * Organized by the Wexner Center + New Work Commissions/Residencies ♦ Catalogue published by WCA ● Gallery Guide ●LaToya Ruby Frazier: The Last Cruze February 1 – August 16, 2020 (END DATE TO BE MODIFIED DUE TO COVID-19) *+●Sadie Benning: Pain Thing February 1 – August 16, 2020 (END DATE TO BE MODIFIED DUE TO COVID-19) *+●Stanya Kahn: No Go Backs January 22 – August 16, 2020 (END DATE TO BE MODIFIED DUE TO COVID-19) *+●HERE: Ann Hamilton, Jenny Holzer, Maya Lin September 21 – December 29, 2019 *+●Barbara Hammer: In This Body (F/V Residency Award) June 1 – August 11, 2019 *Cecilia Vicuña: Lo Precario/The Precarious June 1 – August 11, 2019 Jason Moran June 1 – August 11, 2019 *+●Alicia McCarthy: No Straight Lines February 2 – August 1, 2019 John Waters: Indecent Exposure February 2 – April 28, 2019 Peter Hujar: Speed of Life February 2 – April 28, 2019 *+♦Mickalene Thomas: I Can’t See You Without Me (Visual Arts Residency Award) September 14 –December 30, 2018 *● Inherent Structure May 19 – August 12, 2018 Richard Aldrich Zachary Armstrong Key: * Organized by the Wexner Center ♦ Catalogue published by WCA + New Work Commissions/Residencies ● Gallery Guide Updated July 2, 2020 2 Kevin Beasley Sam Moyer Sam Gilliam Angel Otero Channing Hansen Laura Owens Arturo Herrera Ruth Root Eric N. Mack Thomas Scheibitz Rebecca Morris Amy Sillman Carrie Moyer Stanley Whitney *+●Anita Witek: Clip February 3-May 6, 2018 *●William Kentridge: The Refusal of Time February 3-April 15, 2018 All of Everything: Todd Oldham Fashion February 3-April 15, 2018 Cindy Sherman: Imitation of Life September 16-December 31, 2017 *+●Gray Matters May 20, 2017–July 30 2017 Tauba Auerbach Cristina Iglesias Erin Shirreff Carol Bove Jennie C. -

Thecollective

WORKPLACEGATESHEAD The Old Post Office 19-21 West Street Gateshead, NE8 1AD thecollective Preview: Friday 5th May 6pm – 8pm Exhibition continues: 6th May – 3rd June Opening hours: Tuesday – Saturday 11am – 5pm Issued Wednesday 26th April 2018 Workplace Gateshead is delighted to present the first public exhibition of selected works from The Founding Collective. FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Started in 2002 in London by a group of art professionals and families interested in living with contemporary art The Collective is a growing network of groups collecting, sharing and enjoying contemporary art in their homes or places of work. The combined collection of The Founding Group now comprises over 60 original and limited edition works by emerging and established artists. Selected by Workplace this exhibition includes works by: Mel Brimfield, Jemima Brown, Fiona Banner, Libia Castro & Olafur Olafsson, Martin Creed, Tom Dale, Michael Dean, Tacita Dean, Peter Doig, Bobby Dowler, Tracey Emin, Erica Eyres, Rose Finn-Kelcey, Ceal Floyer, Matthew Higgs, Gareth Jones, Alex Katz, Scott King, Jochen Klein, Edwin Li, Hilary Lloyd, Paul McCarthy, Paul Noble, Chris Ofili, Peter Pommerer, James Pyman, Frances Richardson, Giorgio Sadotti, Jane Simpson, Wolfgang Tillmans, Piotr Uklanski, Mark Wallinger, Bedwyr Williams, and Elizabeth Wright. Free public event: Friday 5th May, 5pm - 6pm, all welcome Founding members of The Collective will give an informal introduction to the history of the group, how it works, how it expanded and plans for the future. This will be followed by an open discussion chaired by WORKPLACE directors Paul Moss and Miles Thurlow focusing on the importance of collecting contemporary art, how to make a start regardless of budget, and the challenges and opportunities for new collectors in the North of England. -

Edwards' First Name at This Sensi

Merlin Carpenter Matthew Collings Our paintings and graphics throw Edwards’ first name at this sensi- discourse of “medium specificity” might be seen as the parents of clear for them how to respond to desire to be a “Goldsmith’s artist” and embarrassment, rather than fact these later developments framework for analysing art’s pop- From my point of view, Carpenter’s It featured work by a handful of Matthew’s style produces any Carpenter and his cronies, plus the opened up within the media: eyes are the wrong colour). It is support group. In this review he Surely society was abolished by But when is this “present”? And referring to a story about Lucas forced to accept that bullshit is as His paintings are brutal abstracts more aesthetic. Some are more Our paintings are against this ap- a good one. But should writing be Media Guy Our PaintinG s down the glove to what’s going tive point. (Perhaps while polishing is an intellectual talking shop full the popularization process having the success of the big push. In on the most grand seriousness. A scene arrives had already terminated yBa, ularity is worth reading. ” (p 124) art practice is often funny. New figures discussed in the book, with serious results in terms of actual more commercially successful ones “a space where the avant-garde‘s certain that Buchloh’s language often seems to be communicating Thatcher? I am not defined by for what audience? This process involving an accident with a piano, natural as breathing and as vital that do little for a renewal of poetic. -

MAT COLLISHAW.STANDING WATER 10 April – 8 July

MAT COLLISHAW.STANDING WATER 10 April – 8 July 2018 Exhibition opening: 10 April 2018, 6 p.m. at the Rudolfinum vestibule Curator: Petr Nedoma To be a member of the Young British Artists, or YBAs, in the first half of the 1990s meant to belong in an art gang that has been largely instrumental in planting British art at the forefront of the global art scene. Mat Collishaw was one of the ‘gang leaders’. His first work – Bullet Hole – which has made his name, was first exhibited at Frieze in 1988, which his close friend Damien Hirst helped organize. The presented works were brutal, monumental; according to the critics, in the best case they referenced and echoed the motif of the doubting Thomas, and in the worst case they aroused sexplicit imaginations. The whole group of artists relished in art inspired by horror, shock, scandal – an approach which had its parallel, as well as foothold in tabloid press – dailies with lurid headlines. However, few people at the time noticed that their art had a deeper and more serious dimension. Over time, those who stuck it out grew more serious, their art more introspective; after twenty years, the deliberate controversy became ingrained in the art establishment – so less interesting, naturally. Paths diverged, every artist looked for their own theme. Mat Collishaw’s (1966) exhibition in Prague, aptly named Standing Water, starts with an almost prophetic and yet programmatic photograph, the artist’s self-portrait Narcissus (1990). The young artist lies in the mud on a London street and, with a kind of ironic exaggeration, contemplates the reflection of his face in a dirty puddle.