Not Lost in Translation: Chemmeen on Alien Shores

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Love and Marriage Across Communal Barriers: a Note on Hindu-Muslim Relationship in Three Malayalam Novels

Love and Marriage Across Communal Barriers: A Note on Hindu-Muslim Relationship in Three Malayalam Novels K. AYYAPPA PANIKER If marriages were made in heaven, the humans would not have much work to do in this world. But fornmately or unfortunately marriages continue to be a matter of grave concern not only for individuals before, during, and/ or after matrimony, but also for social and religious groups. Marriages do create problems, but many look upon them as capable of solving problems too. To the poet's saying about the course of true love, we might add that there are forces that do not allow the smooth running of the course of true love. Yet those who believe in love as a panacea for all personal and social ills recommend it as a sure means of achieving social and religious integration across caste and communal barriers. In a poem written against the backdrop of the 1921 Moplah Rebellion in Malabar, the Malayalam poet Kumaran Asan presents a futuristic Brahmin-Chandala or Nambudiri-Pulaya marriage. To him this was advaita in practice, although in that poem this vision of unity is not extended to the Muslims. In Malayalam fi ction, however, the theme of love and marriage between Hindus and Muslims keeps recurring, although portrayals of the successful working of inter-communal marriages are very rare. This article tries to focus on three novels in Malayalam in which this theme of Hindu-Muslim relationship is presented either as the pivotal or as a minor concern. In all the three cases love flourishes, but marriage is forestalled by unfavourable circumstances. -

Language and Literature

1 Indian Languages and Literature Introduction Thousands of years ago, the people of the Harappan civilisation knew how to write. Unfortunately, their script has not yet been deciphered. Despite this setback, it is safe to state that the literary traditions of India go back to over 3,000 years ago. India is a huge land with a continuous history spanning several millennia. There is a staggering degree of variety and diversity in the languages and dialects spoken by Indians. This diversity is a result of the influx of languages and ideas from all over the continent, mostly through migration from Central, Eastern and Western Asia. There are differences and variations in the languages and dialects as a result of several factors – ethnicity, history, geography and others. There is a broad social integration among all the speakers of a certain language. In the beginning languages and dialects developed in the different regions of the country in relative isolation. In India, languages are often a mark of identity of a person and define regional boundaries. Cultural mixing among various races and communities led to the mixing of languages and dialects to a great extent, although they still maintain regional identity. In free India, the broad geographical distribution pattern of major language groups was used as one of the decisive factors for the formation of states. This gave a new political meaning to the geographical pattern of the linguistic distribution in the country. According to the 1961 census figures, the most comprehensive data on languages collected in India, there were 187 languages spoken by different sections of our society. -

Women at Crossroads: Multi- Disciplinary Perspectives’

ISSN 2395-4396 (Online) National Seminar on ‘Women at Crossroads: Multi- disciplinary Perspectives’ Publication Partner: IJARIIE ORGANISE BY: DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH PSGR KRISHNAMMAL COLLEGE FOR WOMEN, PEELAMEDU, COIMBATORE Volume-2, Issue-6, 2017 Vol-2 Issue-6 2017 IJARIIE-ISSN (O)-2395-4396 A Comparative Study of the Role of Women in New Generation Malayalam Films and Serials Jibin Francis Research Scholar Department of English PSG College of Arts and Science, Coimbatore Abstract This 21st century is called the era of technology, which witnesses revolutionary developments in every aspect of life. The life style of the 21st century people is very different; their attitude and culture have changed .This change of viewpoint is visible in every field of life including Film and television. Nowadays there are several realty shows capturing the attention of the people. The electronic media influence the mind of people. Different television programs target different categories of people .For example the cartoon programs target kids; the realty shows target youth. The points of view of the directors and audience are changing in the modern era. In earlier time, women had only a decorative role in the films. Their representation was merely for satisfying the needs of men. The roles of women were always under the norms and rules of the patriarchal society. They were most often presented on the screen as sexual objects .Here women were abused twice, first by the male character in the film and second, by the spectators. But now the scenario is different. The viewpoint of the directors as well as the audience has drastically changed .In this era the directors are courageous enough to make films with women as central characters. -

13. Ormakai Undayirikkanam English/Malayalam Hindi Hindi

37 Written Answers PHALGUNA15,1918 (Saka) To Questions 38 1 1 14. Ithihasathile Khasak English/Malayalam 22. Neelakkuyil 15. Drip And Sprinkler Irrigation Hindi 23. Adaminte Variyellu 16. The Brief Journey Hindi/English 24. Ore Thooval Pakshikal Homage to Smita Patii 25. Kazhakam 1. Bhumika 26. Unnikuttanu Joli Kitti 2. Chidambaram 27. Kumara Sambhavam Homage to P. A Backer 28. Kilukkam 1. Chappa 29. Amaram 2. Prema Lekhanam 30. Bhargavi Nilayam 3. Manimuzhakkam 31. Sukrutham Tribute to Tapan Sinha 32. Sammohanam 1. Daughters Of The Century Films in the Malayalam Retrospective [Translation] 1. Marthanda Varma Indian Air Services 2. Chemmeen *197. SHRI JAGDAMBI PRASAD YADAV: Will the Minister of CIVIL AVIATION be pleased to state: 3. Iruttinte Atmavu (a) whether Indian Air Services are lagging behind as 4. Olavum Theeravum per the International standards; % 5. Nirmalyam (b) whether these services do not have sufficient number of superior quality planes and whether there is a 6. Elipathayam lack of mechanical facilities for monitoring of air services; 7. Rugmini (c) whether the standard of maintenance of planes is 8. Anubhavangal Palichaka! also very poor; and 9. 1921 (d) if so, the details of the programmes formulated/ likely to be formulated by the Government to bring its air 10. Thinkaiazhcha Nalla Dh/asam services at par with International air services? 11. Manichitra Thazhu THE MINISTER OF CIVIL AVIATION AND MINISTER OF INFORMATION AND BROADCASTING (SHRI C.M. 12. Piravi IBRAHIM): (a) to (d) Air India and Indian Airlines' services 13. Ormakai Undayirikkanam are comparable to International standards. Both Air India and Indian Airlines have adequate 14. -

Translation, Religion and Culture

==================================================================== Language in India www.languageinindia.com ISSN 1930-2940 Vol. 19:1 January 2019 India’s Higher Education Authority UGC Approved List of Journals Serial Number 49042 ==================================================================== Translation, Religion and Culture T. Rubalakshmy =================================================================== Abstract Translation is made for human being to interact with each other to express their love, emotions and trade for their survival. Translators often been hidden into unknown characters who paved the road way for some contribution. In the same time being a translator is very hard and dangerous one. William Tyndale he is in Holland in the year 1536 he worked as a translating the Bible into English. Human needs to understand the culture of the native place where they live. Translator even translates the text and speak many languages. Translators need to have a good knowledge about every language. Translators can give their own opinion while translating. In Malayalam in the novel Chemmeen translated in English by Narayanan Menon titled Chemmeen. This paper is about the relationship between Karuthamma and Pareekutty. Keywords: Chemmeen, translation, languages, relationship, culture, dangerous. Introduction Language is made for human beings. Translating is not an easy task to do from one language to another. Translation has its long history. While translating a novel we have different cultures and traditions. We need to find the equivalent name of a word in translating language. The language and culture are entwined and inseparable Because in many books we have a mythological character, history, customs and ideas. So we face a problem like this while translating a work. Here Thakazhi Sivasankara Pillai also face many problems during translating a work in English . -

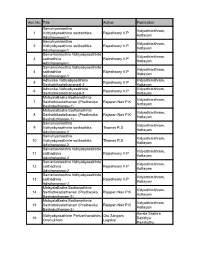

Library Stock.Pdf

Acc.No. Title Author Publication Samuhyashasthra Vidyarthimithram, 1 Vidhyabyasathinte saithadhika Rajeshwary V.P Kottayam Adisthanangal-1 Samuhyashasthra Vidyarthimithram, 2 Vidhyabyasathinte saithadhika Rajeshwary V.P Kottayam Adisthanangal-1 Samaniashasthra Vidhyabyasathinte Vidyarthimithram, 3 saithadhika Rajeshwary V.P Kottayam Adisthanangal-1 Samaniashasthra Vidhyabyasathinte Vidyarthimithram, 4 saithadhika Rajeshwary V.P Kottayam Adisthanangal-1 Adhunika Vidhyabyasathinte Vidyarthimithram, 5 Rajeshwary V.P Saithathikadisthanangal-2 Kottayam Adhunika Vidhyabyasathinte Vidyarthimithram, 6 Rajeshwary V.P Saithathikadisthanangal-2 Kottayam MalayalaBasha Bodhanathinte Vidyarthimithram, 7 Saithathikadisthanam (Pradhesika Rajapan Nair P.K Kottayam Bashabothanam-1) MalayalaBasha Bodhanathinte Vidyarthimithram, 8 Saithathikadisthanam (Pradhesika Rajapan Nair P.K Kottayam Bashabothanam-1) Samuhyashasthra Vidyarthimithram, 9 Vidhyabyasathinte saithadhika Thomas R.S Kottayam Adisthanangal-2 Samuhyashasthra Vidyarthimithram, 10 Vidhyabyasathinte saithadhika Thomas R.S Kottayam Adisthanangal-2 Samaniashasthra Vidhyabyasathinte Vidyarthimithram, 11 saithadhika Rajeshwary V.P Kottayam Adisthanangal-2 Samaniashasthra Vidhyabyasathinte Vidyarthimithram, 12 saithadhika Rajeshwary V.P Kottayam Adisthanangal-2 Samaniashasthra Vidhyabyasathinte Vidyarthimithram, 13 saithadhika Rajeshwary V.P Kottayam Adisthanangal-2 MalayalaBasha Bodhanathinte Vidyarthimithram, 14 Saithathikadisthanam (Pradhesika Rajapan Nair P.K Kottayam Bashabothanam-2) MalayalaBasha -

Research Scholar an International Refereed E-Journal of Literary Explorations

ISSN 2320 – 6101 Research Scholar www.researchscholar.co.in An International Refereed e-Journal of Literary Explorations ASSERTING LOCAL TEXTURE THROUGH SOCIAL NETWORKING Surya Kiran Ph.D. Scholar Department of English University of Hyderabad, (A.P.) Ngugi Wa Thiong’O in his famous essay “The Language of African Literature” has pointed out the adverse impacts of the colonizers language and culture on that of the colonized. After the withdrawal of the colonizers from the land, not many people preferred to preserve and develop the ancestral language and impart it to the next generation. Instead, the colonizers language takes over and mastering the foreigner’s language had by then been established as the key to climbing the charts of social status. This resulted in the development of a “look down up on” attitude towards the regional literatures. This phenomenon is found more in South India, Kerala in particular where English learning has taken importance over Malayalam. The importance given to Dan Brown or J.K. Rowling over Vaikkom Muhammad Basheer or Thakazhi Shivashankara Pillai is not the real concern here, but the fact that there are no many writers in the present day scenario who manage to get past the overwhelming influence of foreign writers using the flavour of regional literature. Globalisation which had brought the English language so close to ordinary people through internet played a crucial role in this development. Blogging and social networking made the English literary arena familiar to one and all and gradually took over the regional writing. Ironically, some excellent pieces of dialectic writing are found in blogs. -

Varsha Adalja Tr. Satyanarayan Swami Pp.280, Edition: 2019 ISBN

HINDI NOVEL Aadikatha(Katha Bharti Series) Rajkamal Chaudhuri Abhiyatri(Assameese novel - A.W) Tr. by Pratibha NirupamaBargohain, Pp. 66, First Edition : 2010 Tr. Dinkar Kumar ISBN 978-81-260-2988-4 Rs. 30 Pp. 124, Edition : 2012 ISBN 978-81-260-2992-1 Rs. 50 Ab Na BasoIh Gaon (Punjabi) Writer & Tr.Kartarsingh Duggal Ab Mujhe Sone Do (A/w Malayalam) Pp. 420, Edition : 1996 P. K. Balkrishnan ISBN: 81-260-0123-2 Rs.200 Tr. by G. Gopinathan Aabhas Pp.180, Rs.140 Edition : 2016 (Award-winning Gujarati Novel ‘Ansar’) ISBN: 978-81-260-5071-0, Varsha Adalja Tr. Satyanarayan Swami Alp jivi(A/w Telugu) Pp.280, Edition: 2019 Rachkond Vishwanath Shastri ISBN: 978-93-89195-00-2 Rs.300 Tr.Balshauri Reddy Pp 138 Adamkhor(Punjabi) Edition: 1983, Reprint: 2015 Nanak Singh Rs.100 Tr. Krishan Kumar Joshi Pp. 344, Edition : 2010 Amrit Santan(A/W Odia) ISBN: 81-7201-0932-2 Gopinath Mohanti (out of stock) Tr. YugjeetNavalpuri Pp. 820, Edition : 2007 Ashirvad ka Rang ISBN: 81-260-2153-5 Rs.250 (Assameese novel - A.W) Arun Sharma, Tr. Neeta Banerjee Pp. 272, Edition : 2012 Angliyat(A/W Gujrati) ISBN 978-81-260-2997-6 Rs. 140 by Josef Mekwan Tr. Madan Mohan Sharma Aagantuk(Gujarati novel - A.W) Pp. 184, Edition : 2005, 2017 Dhiruben Patel, ISBN: 81-260-1903-4 Rs.150 Tr. Kamlesh Singh Anubhav (Bengali - A.W.) Ankh kikirkari DibyenduPalit (Bengali Novel Chokher Bali) Tr. by Sushil Gupta Rabindranath Tagorc Pp. 124, Edition : 2017 Tr. Hans Kumar Tiwari ISBN 978-81-260-1030-1 Rs. -

Feminism and Representation of Women Identities in Indian Cinema: a Case Study

FEMINISM AND REPRESENTATION OF WOMEN IDENTITIES IN INDIAN CINEMA: A CASE STUDY Amaljith N.K1 Manonmaniam Sundaranar University, India. Abstract The film is one of the most popular sources of entertainment worldwide. Plentiful films are produced each year and the amount of spectators is also huge. Films are to be called as the mirror of society, because they portray the actual reality of the society through the cinematography. Thus, cinema plays an essential role in shaping views about, caste, creed and gender. There are many pieces of research made on the representation of women or gender in films. But, through this research, the researcher wants to analyse in- depth about the character representation of women in the Malayalam film industry how strong the so-called Mollywood constructs the strongest and stoutest women characters in Malayalam cinema in the 21st-century cinema. This study confers how women are portrayed in the Malayalam cinema in the 21st century and how bold and beautiful are the women characters in Malayalam film industry are and how they act and survive the social stigma and stereotypes in their daily life. All sample films discuss the plights and problems facing women in contemporary society and pointing fingers towards the representation of women in society. The case study method is used as the sole Methodology for research. And Feminist Film theory and theory of patriarchy applied in the theoretical framework. Keywords: Gender, Women, Film, Malayalam, Representation, Feminism. Feminismo e representação da identidade de mulheres no cinema indiano: um estudo de caso Resumo O filme é uma das fontes de entretenimento mais populares em todo o mundo. -

A Study on Time by Mtvasudevan Nair

European Journal of Molecular & Clinical Medicine ISSN 2515-8260 Volume 07, Issue 07, 2020 Socio-Cultural Transformation: A Study On Time By M.T.Vasudevan Nair Dr. Digvijay Pandya1, Ms. Devisri B2 1Associate Professor, Department of English, Lovely Professional University, Punjab, India. 2Doctoral Research Scholar, Department of English, Punjab, India. ABSTRACT: Kerala, the land is blessed with nature and its tradition. It has a copiously diverse vegetation beautiful landscape and climate. The land is also rich in its literature. M.T.Vasudevan Nair is one of the renowned figures in Malayalam literature who excels and portrays the traditional and cultural picture of Kerala society. Kaalam, published in 1969 is a lyrical novel in Malayalam literature by M.T.Vasudevan Nair and Gita Krishnan Kutty translates it into English as Time. This paper tries to analyse the sociological and cultural transformation of Kerala in the novel Time during the period of MT. It also focuses on the system of Marumakkathayam,joint family system and its transformation. Keywords: Sociological and Cultural transformation, Marumakkathayam, Joint family system, Tarawads. India is a multi-lingual country steeped in its rich culture and tradition. There are many such treasure troves of creativity in the regional languages that would have been lost to the rest of the world, but for its tradition, which is the only means to reach a wider group of reading public. Tradition helps to understand the thought process of the people of a particular region against the backdrop of socio-cultural roots. Malayalam is one of the multifaceted languages in India. Malayalam, the mother tongue of nearly thirty million Malayalis, ninety percent of whom living in Kerala state in the south – west corner of India, belongs to the Dravidian family of languages. -

The Fall of Customs in the Chemmeen IJAR 2015; 1(3): 88-89 Received: 15-01-2015 Nidhi Malik Accepted: 16-02-2015

International Journal of Applied Research 2015; 1(3): 88-89 ISSN Print: 2394-7500 ISSN Online: 2394-5869 Impact Factor: 3.4 The fall of customs in the Chemmeen IJAR 2015; 1(3): 88-89 www.allresearchjournal.com Received: 15-01-2015 Nidhi Malik Accepted: 16-02-2015 Nidhi Malik Abstract Trained Graduate Teacher “Chemmeen” is the narrative of the fisherman’s society. Ordinary forces are severely genuine adversary (English), Directorate of or acquaintances. It is far-off from a municipality vision of living. The fundamentals can obliterate a Education, Govt. Of NCT of human being and his relatives; they can also construct it probable to survive for an additional year, that Delhi is, accordingly in the insignificant fishing societies it is the uncompromising spirit Katalamma, who instructions the conviction of the persons. She lives at the conviction of the persons. She lives at the underneath of the sea and the technique to her dwelling is completed appalling by vortex and untrustworthy contemporary. Mercilessly she castigates the depraved, negligent them downwards to her dreadful kingdom and sending sea monstrous and serpents to the seashore as a caution of the anger. The men at sea must be courageous and honourable. The women on seashore must be uncontaminated and uncorrupted to assurance the protection of their men on Katalamma’s dangerous waters. Keywords: Society, untrustworthy, dreadful, municipality. 1. Introduction Thakazhi Sivasankara Pillai is among the brand of writers who ushered Malayalam literature into a new age. His place in Malayalam literature is that of a god-father. Chemmeen is Pillai’s best novel which expresses the aspirations, struggle and grief in the lives of the fisherman of Kerala. -

Poverty, Shame and Social Exclusion

Draft- not for citation without prior permission of authors Poverty, Shame and Social Exclusion Working Paper 1 India Cultural conceptions of poverty associated shame: Analysis of Indian Cinema and Short stories Leemamol Mathew Sony Pellissery 2012 Dr. Leemamol Mathew, Institute of Rural Management, Anand, India [email protected] Dr. Sony Pellissery , Institute of Rural Management, Anand, India [email protected] 1 Draft- not for citation without prior permission of authors Cultural conceptions of poverty associated shame: Analysis of Indian Cinema and Short stories Introduction India is home to the largest number of poor people in the world. Of 1.13 billion people, 27.8 per cent live below the poverty line (below the accepted income level of consumption requirements according to the conservative standards of the Indian government). The face of this deep and persistent poverty is observable in poor spending on health, undignified ageing, poor educational standards, malnourished bodies, inferior housing, poor infrastructure resulting in deterioration in the quality of life, child labour, poor service delivery, less importance attached to safety measures etc. All of them have severe implications for inter- personal relationships within the household, village, work place, and in the larger community. Concurrently, in recent times, wealth accumulation through businesses in India is reported, indicating increasing economic inequality. On the other hand, India is also marked by another interesting phenomenon. It is the home of origin for the largest number of religions. Buddhism, Jainism, Hinduism, Sikhism were all born in India. It is also important to note the peculiar institution of caste, i.e., dividing human beings into social hierarchies according to their occupation, which is peculiar to Indian culture.