Dance-Type Narration in Stanisław Moniuszko's Operas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’S Opera and Concert Arias Joshua M

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Doctoral Dissertations University of Connecticut Graduate School 10-3-2014 The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’s Opera and Concert Arias Joshua M. May University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation May, Joshua M., "The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’s Opera and Concert Arias" (2014). Doctoral Dissertations. 580. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations/580 ABSTRACT The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’s Opera and Concert Arias Joshua Michael May University of Connecticut, 2014 W. A. Mozart’s opera and concert arias for tenor are among the first music written specifically for this voice type as it is understood today, and they form an essential pillar of the pedagogy and repertoire for the modern tenor voice. Yet while the opera arias have received a great deal of attention from scholars of the vocal literature, the concert arias have been comparatively overlooked; they are neglected also in relation to their counterparts for soprano, about which a great deal has been written. There has been some pedagogical discussion of the tenor concert arias in relation to the correction of vocal faults, but otherwise they have received little scrutiny. This is surprising, not least because in most cases Mozart’s concert arias were composed for singers with whom he also worked in the opera house, and Mozart always paid close attention to the particular capabilities of the musicians for whom he wrote: these arias offer us unusually intimate insights into how a first-rank composer explored and shaped the potential of the newly-emerging voice type of the modern tenor voice. -

Cantabile Hendrik Waelput

Cantabile for 4 Violas Hendrik Waelput (1845–1885) AVS Publications 018 Preface The Flemish composer and conductor Hendrik Waelput studied music at the Royal Conservatory in Brussels and was awarded the Prix de Rome for his cantata Het woud in 1867. Waelput was active as a conductor in several European cities before returning to his home town of Ghent in 1875. There, he conducted various orchestras and taught harmony and counterpoint at the Conservatory in Antwerp. Waelput’s compositions include larger forms (operas, symphonies, and choral music) and chamber music, including a string quintet (viola quintet), a Canzonetta for string quartet, and this Cantabile for four violas. While the impetus behind this particular work is unknown, his use of four identical instruments in a composition is not unique: he also wrote an Andante Cantabile for four trombones and featured four solo cellos in the Andante Cantabile movement of his Flute Concerto. This edition is based on an undated manuscript score and set of parts housed in the Library Conservatorium Ghent, BG. David M. Bynog, editor Cantabile for 4 violas Hendrik Waelput Edited by David M. Bynog Andante Cantabile Viola 1 # œ œ. œ œ > œ œ œ 3 œ. œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ. œ œ œ & 4 œ. œ œ œ 3 cresc. p œ Viola 2 œ œ œ œ œ #œ #œ œ > œ B # 3 ˙ œ ˙ œ œ œ# ˙ 4 cresc. p Viola 3 # œ bœ B 43 œ ˙ œ ˙ œ œ œ œ œ #œ #œ œ œ nœ œ œ > cresc. -

UNDERSTANDING OPERA Spring 2013 - Syllabus

Boston University College of Fine Arts, School of Music MU710: SPECIAL TOPICS: UNDERSTANDING OPERA Spring 2013 - Syllabus - Instructor: Deborah Burton Office hours: CFA 223, by appointment Telephone: (617) 353-5483 Email: [email protected] Meeting Times and Location: Tuesdays and Thursdays, 11:00 - 12:30, CFA 219 Course Description and Objectives What is opera? How is it different than a play or a film? Is there anything that Monteverdi’s Orfeo (1600) has in common with Berg’s Wozzeck (1921)? (The answer is “yes.”) How can we understand this complex art-form in a meaningful way? Exploring opera from its beginnings c. 1600 to the present, this course is a seminar that focuses on close readings of scores and their text /music relationships through a primarily analytic lens. Discussions, in general chronological order, will center on the problem of analyzing opera, and the analytic application to these multilayered texts of phrase rhythms, sonata forms, la solita forma and extended/interrupted harmonic structures. Prerequisite CFA MU 601 or equivalent Required Texts There are no required texts for this class. Scores can be downloaded from www.imslp.com or borrowed from Mugar library. A recommended text is Piero Weiss, ed. Opera: A History in Documents (New York: Oxford University Press, 2002), available at the BU Bookstore. Course Grade Components • Attendance and participation 25% • Presentation 1 10% • Presentation 2 10% • Presentation 3 10% • Presentation 4 10% • Short assignments 10% • Final project 25% 2 Short assignments: • Occasional short listening and study assignments will be made in the course of the semester. Recordings containing all the assigned material for listening will be on reserve at the library and/or available through the course Blackboard site. -

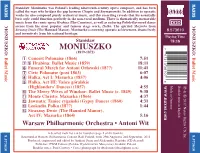

Moniuszko Was Poland’S Leading Nineteenth-Century Opera Composer, and Has Been Called the Man Who Bridges the Gap Between Chopin and Szymanowski

CMYK NAXOS NAXOS Stanisław Moniuszko was Poland’s leading nineteenth-century opera composer, and has been called the man who bridges the gap between Chopin and Szymanowski. In addition to operatic works he also composed purely orchestral music, and this recording reveals that his essentially lyric style could function perfectly in the non-vocal medium. There is thematically memorable music from the comic opera Hrabina (The Countess), as well as enduring Polish-flavoured dance DDD MONIUSZKO: scenes from his most popular and famous stage work, Halka. The spirited Mazurka from MONIUSZKO: Straszny Dwór (The Haunted Manor), Moniuszko’s crowning operatic achievement, draws freely 8.573610 and inventively from his national heritage. Playing Time Stanisław 78:18 MONIUSZKO 7 (1819-1872) 47313 36107 Ballet Music 1 Concert Polonaise (1866) 7:51 Ballet Music 2-5 Hrabina: Ballet Music (1859) 18:11 6 Funeral March for Antoni Orłowski (18??) 11:41 7 Civic Polonaise (post 1863) 6:07 8 Halka, Act I: Mazurka (1857) 4:06 9 Halka, Act III: Tańce góralskie 6 (Highlanders’ Dances) (1857) 4:55 www.naxos.com Made in Germany Booklet notes in English ൿ 0 The Merry Wives of Windsor: Ballet Music (c. 1849) 9:38 & Ꭿ ! Monte Christo: Mazurka (1866) 4:37 2017 Naxos Rights US, Inc. @ Jawnuta: Taniec cygański (Gypsy Dance) (1860) 4:31 # Leokadia Polka (18??) 1:44 $ Straszny Dwór (The Haunted Manor), Act IV: Mazurka (1864) 5:16 Warsaw Philharmonic Orchestra • Antoni Wit A detailed track list can be found on page 2 of the booklet. 8.573610 8.573610 Recorded at Warsaw Philharmonic Concert Hall, Poland, from 29th August to 2nd September, 2011 Produced, engineered and edited by Andrzej Sasin and Aleksandra Nagórko (CD Accord) Publisher: PWM Edition (Polskie Wydawnictwo Muzyczne), Kraków, Poland Booklet notes: Paul Conway • Cover photograph by dzalcman (iStockphoto.com). -

Performance Practice Bibliography (1995-1996)

Performance Practice Review Volume 9 Article 11 Number 2 Fall Performance Practice Bibliography (1995-1996) Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/ppr Part of the Music Practice Commons (1996) "Performance Practice Bibliography (1995-1996)," Performance Practice Review: Vol. 9: No. 2, Article 11. DOI: 10.5642/ perfpr.199609.02.11 Available at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/ppr/vol9/iss2/11 This Bibliography is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Claremont at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Performance Practice Review by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PERFORMANCE PRACTICE BIBLIOGRAPHY (1995-1996)* Contents Surveys 212 The Ninth to Thirteenth Century 215 The Sixteenth Century 215 The Seventeenth Century 219 The Early Eighteenth Century 225 The Late Eighteenth Century 229 The Nineteenth Century 232 The Twentieth Century 235 Reflections on Performance Practice 238 SURVEYS Voices 1. Giles, Peter. The History and Technique of the Coun- ter-Tenor: a Study of the Male High Voice Family. Hants (England): Scolar Press, 1994, xxiv-459p. (ISBN 85967 931 4). Considers all high male voice types: falsetto, castrato, countertenor, male alto, male soprano. For Giles the true countertenor is a falsetto male alto who has developed a bright, clear tone. The countertenor head-voice uses the full length of folds and has developed "pharyngeal" singing between the basic and falsetto mechanisms. That "upper falsetto" (to which Caccini and others were averse) is the true falsetto is a misconception. As Rene Jacobs has indicated head- Containing as well a number of earlier citations. -

Gioachino Rossini the Journey to Rheims Ottavio Dantone

_____________________________________________________________ GIOACHINO ROSSINI THE JOURNEY TO RHEIMS OTTAVIO DANTONE TEATRO ALLA SCALA www.musicom.it THE JOURNEY TO RHEIMS ________________________________________________________________________________ LISTENING GUIDE Philip Gossett We know practically nothing about the events that led to the composition of Il viaggio a Reims, the first and only Italian opera Rossini wrote for Paris. It was a celebratory work, first performed on 19 June 1825, honoring the coronation of Charles X, who had been crowned King of France at the Cathedral of Rheims on 29 May 1825. After the King returned to Paris, his coronation was celebrated in many Parisian theaters, among them the Théâtre Italien. The event offered Rossini a splendid occasion to present himself to the Paris that mattered, especially the political establishment. He had served as the director of the Théatre Italien from November 1824, but thus far he had only reproduced operas originally written for Italian stages, often with new music composed for Paris. For the coronation opera, however, it proved important that the Théâtre Italien had been annexed by the Académie Royale de Musique already in 1818. Rossini therefore had at his disposition the finest instrumentalists in Paris. He took advantage of this opportunity and wrote his opera with those musicians in mind. He also drew on the entire company of the Théâtre Italien, so that he could produce an opera with a large number of remarkable solo parts (ten major roles and another eight minor ones). Plans for multitudinous celebrations for the coronation of Charles X were established by the municipal council of Paris in a decree of 7 February 1825. -

Grand Finals Concert

NATIONAL COUNCIL AUDITIONS grand finals concert conductor Metropolitan Opera Carlo Rizzi National Council Auditions host Grand Finals Concert Anthony Roth Costanzo Sunday, March 31, 2019 3:00 PM guest artist Christian Van Horn Metropolitan Opera Orchestra The Metropolitan Opera National Council is grateful to the Charles H. Dyson Endowment Fund for underwriting the Council’s Auditions Program. general manager Peter Gelb jeanette lerman-neubauer music director Yannick Nézet-Séguin 2018–19 SEASON NATIONAL COUNCIL AUDITIONS grand finals concert conductor Carlo Rizzi host Anthony Roth Costanzo guest artist Christian Van Horn “Dich, teure Halle” from Tannhäuser (Wagner) Meghan Kasanders, Soprano “Fra poco a me ricovero … Tu che a Dio spiegasti l’ali” from Lucia di Lammermoor (Donizetti) Dashuai Chen, Tenor “Oh! quante volte, oh! quante” from I Capuleti e i Montecchi (Bellini) Elena Villalón, Soprano “Kuda, kuda, kuda vy udalilis” (Lenski’s Aria) from Today’s concert is Eugene Onegin (Tchaikovsky) being recorded for Miles Mykkanen, Tenor future broadcast “Addio, addio, o miei sospiri” from Orfeo ed Euridice (Gluck) over many public Michaela Wolz, Mezzo-Soprano radio stations. Please check “Seul sur la terre” from Dom Sébastien (Donizetti) local listings. Piotr Buszewski, Tenor Sunday, March 31, 2019, 3:00PM “Captain Ahab? I must speak with you” from Moby Dick (Jake Heggie) Thomas Glass, Baritone “Don Ottavio, son morta! ... Or sai chi l’onore” from Don Giovanni (Mozart) Alaysha Fox, Soprano “Sorge infausta una procella” from Orlando (Handel) -

A European Singspiel

Columbus State University CSU ePress Theses and Dissertations Student Publications 2012 Die Zauberflöte: A urE opean Singspiel Zachary Bryant Columbus State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://csuepress.columbusstate.edu/theses_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Bryant, Zachary, "Die Zauberflöte: A urE opean Singspiel" (2012). Theses and Dissertations. 116. https://csuepress.columbusstate.edu/theses_dissertations/116 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Publications at CSU ePress. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of CSU ePress. r DIE ZAUBEFL5TE: A EUROPEAN SINGSPIEL Zachary Bryant Die Zauberflote: A European Singspiel by Zachary Bryant A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of Requirements of the CSU Honors Program for Honors in the Bachelor of Arts in Music College of the Arts Columbus State University Thesis Advisor JfAAlj LtKMrkZny Date TttZfQjQ/Aj Committee Member /1^^^^^^^C^ZL^>>^AUJJ^AJ (?YUI£^"QdJu**)^-) Date ^- /-/<£ Director, Honors Program^fSs^^/O ^J- 7^—^ Date W3//±- Through modern-day globalization, the cultures of the world are shared on a daily basis and are integrated into the lives of nearly every person. This reality seems to go unnoticed by most, but the fact remains that many individuals and their societies have formed a cultural identity from the combination of many foreign influences. Such a multicultural identity can be seen particularly in music. Composers, artists, and performers alike frequently seek to incorporate separate elements of style in their own identity. One of the earliest examples of this tradition is the German Singspiel. -

Understanding Music Past and Present

Understanding Music Past and Present N. Alan Clark, PhD Thomas Heflin, DMA Jeffrey Kluball, EdD Elizabeth Kramer, PhD Understanding Music Past and Present N. Alan Clark, PhD Thomas Heflin, DMA Jeffrey Kluball, EdD Elizabeth Kramer, PhD Dahlonega, GA Understanding Music: Past and Present is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribu- tion-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. This license allows you to remix, tweak, and build upon this work, even commercially, as long as you credit this original source for the creation and license the new creation under identical terms. If you reuse this content elsewhere, in order to comply with the attribution requirements of the license please attribute the original source to the University System of Georgia. NOTE: The above copyright license which University System of Georgia uses for their original content does not extend to or include content which was accessed and incorpo- rated, and which is licensed under various other CC Licenses, such as ND licenses. Nor does it extend to or include any Special Permissions which were granted to us by the rightsholders for our use of their content. Image Disclaimer: All images and figures in this book are believed to be (after a rea- sonable investigation) either public domain or carry a compatible Creative Commons license. If you are the copyright owner of images in this book and you have not authorized the use of your work under these terms, please contact the University of North Georgia Press at [email protected] to have the content removed. ISBN: 978-1-940771-33-5 Produced by: University System of Georgia Published by: University of North Georgia Press Dahlonega, Georgia Cover Design and Layout Design: Corey Parson For more information, please visit http://ung.edu/university-press Or email [email protected] TABLE OF C ONTENTS MUSIC FUNDAMENTALS 1 N. -

Opera Wrocławska

OPERA WROCŁAWSKA ~ INSTYTUCJA KULTURY SAMORZĄDU WOJEWÓDZTWA DOLNOSLĄSKIEGO WSPÓŁPROWADZONA PRZEZ MINISTRA KULTURY I DZIEDZICTWA NARODOWEGO EWA MICHNIK DYREKTOR NAUELNY I ARTYSTYUNY STRASZNY DWÓR THE HAUNTED MANOR STANISŁAW MONIUSZKO OPERA W 4 AKTACH I OPERA IN 4 ACTS JAN CHĘCIŃSKI LIBR ETIO WARSZAWA, 1865 PRAPREMIERA I PREVIEW SPEKTAKLE PREMIEROWE I PREMIERES 00 PT I FR 6 111 2009 I 19 SO I SA 7 Ili 2009 I 19 00 00 ND I SU 8 Ili 2009 117 CZAS TRWANIA SPEKTAKLU 180 MIN. I DURATION 180 MIN . 1 PRZERWA I 1 PAUSE SPEKTAKL WYKONYWANY JEST W JĘZYKU POLSKIM Z POLSKIMI NAPISAMI POLI SH LANGUAGE VERSION WITH SURTITLES STRASZNY DWÓR I THE HAU~TED MAl\ OR REALIZATO RZY I PRODUCERS OBSADA I CAST REALIZATORZY I PROOUCERS MIECZNIK MACIEJ TOMASZ SZREDER ZBIGNIEW KRYCZKA JAROSŁAW BODAKOWSKI KIEROWNICTWO MUZYCZNE, DYRYGENT I MUSICAL DIRECTION, CONDUCTOR BOGUSŁAW SZYNALSKI* JACEK JASKUŁA LACO ADAMIK STEFAN SKOŁUBA INSCENIZACJA I REŻYSERIA I STAGE DIRECTION RAFAŁ BARTMIŃSKI* WIKTOR GORELIKOW ARNOLD RUTKOWSKI* RADOSŁAW ŻUKOWSKI BARBARA KĘDZIERSKA ALEKSANDER ZUCHOWICZ* SCENOGRAFIA I SET & COSTUME DESIGNS DAMAZY ZBIGNIEW ANDRZEJ KALININ MAGDALENA TESŁAWSKA, PAWEŁ GRABARCZYK DAMIAN KONIECZEK KAROL KOZŁOWSKI WSPÓŁPRACA SCENOGRAFICZNA I SET & COSTUME DE SIGNS CO-OPERATION TOMASZ RUDNICKI EDWARD KULCZYK RAFAŁ MAJZNER HENRYK KONWIŃSKI HANNA CHOREOGRAFIA I CHOREOGRAPHY EWA CZERMAK STARSZA NIEWIASTA ALEKSANDRA KUBAS JOLANTA GÓRECKA MAŁGORZATA ORAWSKA JOANNA MOSKOWICZ PRZYGOTOWANIE CHÓRU I CHORUS MASTER MARTA JADWIGA URSZULA CZUPRYŃSKA BOGUMIŁ PALEWICZ ANNA BERNACKA REŻYSERIA ŚWIATEŁ I LIGHTING DESIGNS DOROT A DUTKOWSKA GRZEŚ PIOTR BUNZLER HANNA MARASZ CZEŚNIKOWA ASYSTENT REŻYS ERA I ASS ISTAN T TO THE STAGE DIRECTOR BARBARA BAGIŃSKA SOLIŚCI, ORKIESTRA, CHÓR I BALET ELŻBIETA KACZMARZYK-JANCZAK OPERY WROCŁAWSKIEJ, STATYŚCI ADAM FRONTCZAK, JULIAN ŻYCHOWICZ ALEKSANDRA LEMISZKA SOLOISTS, ORCHESTRA, CHOIR AND BALLET INSPICJENCI I SRTAGE MANAGERS OF THE WROCŁAW OPERA, SUPERNUMERARIES * gościnnie I spec1al guest Dyrekcja zastrzega sobie prawo do zmian w obsadach . -

Understanding the Lirico-Spinto Soprano Voice Through the Repertoire of Giovane Scuola Composers

UNDERSTANDING THE LIRICO-SPINTO SOPRANO VOICE THROUGH THE REPERTOIRE OF GIOVANE SCUOLA COMPOSERS Youna Jang Hartgraves Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS August 2017 APPROVED: Jeffrey Snider, Major Professor William Joyner, Committee Member Silvio De Santis, Committee Member Stephen Austin, Chair of the Division of Vocal Studies Benjamin Brand, Director of Graduate Studies in the College of Music John Richmond, Dean of the College of Music Victor Prybutok, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Hartgraves, Youna Jang. Understanding the Lirico-Spinto Soprano Voice through the Repertoire of Giovane Scuola Composers. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), August 2017, 53 pp., 10 tables, 6 figures, bibliography, 66 titles. As lirico-spinto soprano commonly indicates a soprano with a heavier voice than lyric soprano and a lighter voice than dramatic soprano, there are many problems in the assessment of the voice type. Lirico-spinto soprano is characterized differently by various scholars and sources offer contrasting and insufficient definitions. It is commonly understood as a pushed voice, as many interpret spingere as ‘to push.’ This dissertation shows that the meaning of spingere does not mean pushed in this context, but extended, thus making the voice type a hybrid of lyric soprano voice type that has qualities of extended temperament, timbre, color, and volume. This dissertation indicates that the lack of published anthologies on lirico-spinto soprano arias is a significant reason for the insufficient understanding of the lirico-spinto soprano voice. The post-Verdi Italian group of composers, giovane scuola, composed operas that required lirico-spinto soprano voices. -

Nature, Weber and a Revision of the French Sublime

Nature, Weber and a Revision of the French Sublime Naturaleza, Weber y una revisión del concepto francés de lo sublime Joseph E. Morgan Nature, Weber, and a Revision of the French Sublime Joseph E. Morgan This article investigates the emergence Este artículo aborda la aparición y and evolution of two mainstream evolución de dos de los grandes temas romantic tropes (the relationship románticos, la relación entre lo bello y between the beautiful and the sublime lo sublime, así como la que existe entre as well as that between man and el hombre y la naturaleza, en la nature) in the philosophy, aesthetics filosofía, la estética y la pintura de la and painting of Carl Maria von Weber’s época de Carl Maria von Weber. El foco time, directing it towards an analysis of se dirige hacia el análisis de la expresión Weber’s musical style and expression as y el estilo musicales de Weber, tal y manifested in his insert aria for Luigi como se manifiesta en la inserción de Cherubini’s Lodoïska “Was Sag Ich,” (J. su aria “Was sag ich?” (J.239) que 239). The essay argues that the escribió para la ópera Lodoïska de Luigi cosmopolitan characteristic of Weber’s Cherubini. Este estudio propone que el operatic expression, that is, his merging carácter cosmopolita de las óperas de of French and Italian styles of operatic Weber (con su fusión de los estilos expression, was a natural consequence operísticos francés e italiano) fue una of his participation in the synaesthetic consecuencia natural de su movement of the Romantic era.