The Material Background of the Earliest Civilization in Crete

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alpine Ibex, Capra Ibex

(CAPRA IBEX) ALPINE IBEX by: Braden Stremcha EVOLUTION Alpine ibex is part of the Bovidae family under the order Artiodactyla. The Capra genus signifies this species specifically as a wild goat, but this genus shares very similar evolutionary features as species we recognize in Montana like Oreamnos (mountain goat) and Ovis (sheep). Capra, Oreamnos, and Ovis most likely derived in evolution from each other due to glacial migration and failure to hybridize between genera and species.Capra ibex was first historically observed throughout the central Alpine Range of Europe, then was decreased to Grand Paradiso National Park in Italy and the Maurienne Valley in France but has since been reintroduced in multiple other countries across the Alps. FORM AND FUNCTION Capra ibex shares a typical hoofed unguligrade foot posture, a cannon bone with raised calcaneus, and the common cursorial locomotion associated with species in Artiodactyla. These features allow the alpine ibex to maneuver through the steep terrain in which they reside. Specifically, for alpine ungulates and the alpine ibex, more energy is put into balance and strength to stay on uneven terrain than moving long distances. Alpine ibexes are often observed climbing artificial dams that are almost vertical to lick mineral deposits! This example shows how efficient Capra ibex is at navigating steep and dangerous terrain. The most visual distinction that sets the Capra genus apart from others is the large, elongated semicircular horns. Alpine ibex specifically has horns that grow throughout their life span at an average of 80mm per year in males. When winter comes around this growth is stunted until spring and creates an obvious ring on the horn that signifies that year’s overall growth. -

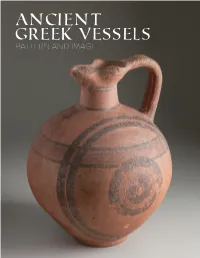

Ancient Greek Vessels Pattern and Image

ANCIENT GREEK VESSELS PATTERN AND IMAGE 1 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS It is my pleasure to acknowledge the many individuals who helped make this exhibition possible. As the first collaboration between The Trout Gallery at Dickinson College and Bryn Mawr and Wilson Colleges, we hope that this exhibition sets a precedent of excellence and substance for future collaborations of this sort. At Wilson College, Robert K. Dickson, Associate Professor of Fine Art and Leigh Rupinski, College Archivist, enthusiasti- cally supported loaning the ancient Cypriot vessels seen here from the Barron Blewett Hunnicutt Classics ANCIENT Gallery/Collection. Emily Stanton, an Art History Major, Wilson ’15, prepared all of the vessels for our initial selection and compiled all existing documentation on them. At Bryn Mawr, Brian Wallace, Curator and Academic Liaison for Art and Artifacts, went out of his way to accommodate our request to borrow several ancient Greek GREEK VESSELS vessels at the same time that they were organizing their own exhibition of works from the same collection. Marianne Weldon, Collections Manager for Special Collections, deserves special thanks for not only preparing PATTERN AND IMAGE the objects for us to study and select, but also for providing images, procuring new images, seeing to the docu- mentation and transport of the works from Bryn Mawr to Carlisle, and for assisting with the installation. She has been meticulous in overseeing all issues related to the loan and exhibition, for which we are grateful. At The Trout Gallery, Phil Earenfight, Director and Associate Professor of Art History, has supported every idea and With works from the initiative that we have proposed with enthusiasm and financial assistance, without which this exhibition would not have materialized. -

Poison King: the Life and Legend of Mithradates the Great, Rome's

Copyrighted Material Kill em All, and Let the Gods Sort em Out IN SPRING of 88 BC, in dozens of cities across Anatolia (Asia Minor, modern Turkey), sworn enemies of Rome joined a secret plot. On an appointed day in one month’s time, they vowed to kill every Roman man, woman, and child in their territories. e conspiracy was masterminded by King Mithradates the Great, who communicated secretly with numerous local leaders in Rome’s new Province of Asia. (“Asia” at this time referred to lands from the eastern Aegean to India; Rome’s Province of Asia encompassed western Turkey.) How Mithradates kept the plot secret remains one of the great intelli- gence mysteries of antiquity. e conspirators promised to round up and slay all the Romans and Italians living in their towns, including women and children and slaves of Italian descent. ey agreed to confiscate the Romans’ property and throw the bodies out to the dogs and crows. Any- one who tried to warn or protect Romans or bury their bodies was to be harshly punished. Slaves who spoke languages other than Latin would be spared, and those who joined in the killing of their masters would be rewarded. People who murdered Roman moneylenders would have their debts canceled. Bounties were offered to informers and killers of Romans in hiding.1 e deadly plot worked perfectly. According to several ancient histo- rians, at least 80,000—perhaps as many as 150,000—Roman and Italian residents of Anatolia and Aegean islands were massacred on that day. e figures are shocking—perhaps exaggerated—but not unrealistic. -

Pavlopetri, an Underwater Bronze Age Town in Laconia

Pavlopetri, an Underwater Bronze Age Town in Laconia Author(s): Anthony Harding, Gerald Cadogan and Roger Howell Reviewed work(s): Source: The Annual of the British School at Athens, Vol. 64 (1969), pp. 113-142 Published by: British School at Athens Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/30103334 . Accessed: 25/01/2013 06:05 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. British School at Athens is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Annual of the British School at Athens. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded on Fri, 25 Jan 2013 06:05:23 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions Vatika Plain 3 NORTH tp ,rcP E~o Pet i~aaa~~aaa~: ,b nE kL hphod 4'0 Poriki Isles LEa Ano~ 50 VA T KA BAY "d; SSi Nt. a00, Saracenf'koSaraceniko Bay "- ovo(i1" -M 4w0 4co a50 sea depthsin fathoms 0 km 1 2 3 t 5 6 sea miles 1 2 3 0 FIG. I. PAVLOPETRI, ELAPHONISOS AND THE BAY OF M.W. 3o . 496,. This content downloaded on Fri, 25 Jan 2013 06:05:23 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions tika Plain NORTH NE L VAT KA BAY Mt. -

Kretan Cult and Customs, Especially in the Classical and Hellenistic Periods: a Religious, Social, and Political Study

i Kretan cult and customs, especially in the Classical and Hellenistic periods: a religious, social, and political study Thesis submitted for degree of MPhil Carolyn Schofield University College London ii Declaration I, Carolyn Schofield, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been acknowledged in the thesis. iii Abstract Ancient Krete perceived itself, and was perceived from outside, as rather different from the rest of Greece, particularly with respect to religion, social structure, and laws. The purpose of the thesis is to explore the bases for these perceptions and their accuracy. Krete’s self-perception is examined in the light of the account of Diodoros Siculus (Book 5, 64-80, allegedly based on Kretan sources), backed up by inscriptions and archaeology, while outside perceptions are derived mainly from other literary sources, including, inter alia, Homer, Strabo, Plato and Aristotle, Herodotos and Polybios; in both cases making reference also to the fragments and testimonia of ancient historians of Krete. While the main cult-epithets of Zeus on Krete – Diktaios, associated with pre-Greek inhabitants of eastern Krete, Idatas, associated with Dorian settlers, and Kretagenes, the symbol of the Hellenistic koinon - are almost unique to the island, those of Apollo are not, but there is good reason to believe that both Delphinios and Pythios originated on Krete, and evidence too that the Eleusinian Mysteries and Orphic and Dionysiac rites had much in common with early Kretan practice. The early institutionalization of pederasty, and the abduction of boys described by Ephoros, are unique to Krete, but the latter is distinct from rites of initiation to manhood, which continued later on Krete than elsewhere, and were associated with different gods. -

Mobility of Deities? the Territorial and Ideological Expansion of Knossos

Krzysztof Nowicki Mobility of deities? The territorial and ideological expansion of Knossos during the Proto-Palatial period as evidenced by the peak sanctuaries distribution, development, and decline Abstract This paper proposes a new explanation of the intriguing distribution pattern of peak sanctuaries in Crete during the MM period, and the reasons for their fast expansion in the late Proto-Palatial period, followed by a sudden decline soon afterwards. The working hypothesis presented here is based on my intensive fieldwork carried out during the last decade and is supported by several recently identified sites which shed new light on these problems. At present about 40 sites in Crete can be classified as peak sanctuaries. They are mostly grouped in three regions: central Crete, the East Siteia peninsula and the Rethymnon isthmus, with a few “anomalous” sites beyond these regions. It is indisputable that the earliest, the most important and the longest-lived peak sanctuary was Iouchtas, closely related to Knossos. Iouchtas became a model-site, the idea of which spread to other parts of the island. Some regions, however, as for example those controlled by Malia and Phaistos, showed strong resistance to it. It will be argued in this paper that the peak sanctuary on Iouchtas did not reflect a universal idea of a mountain deity shared by all Cretans, but rather represented a local Knossian concept of a holy mountain which later became the sanctuary of a young storm-god (?), the protector of Knossos. The distribution of peak sanctuaries may thus represent the territorial and/or ideological expansion of Knossos during the MM IB and MM II periods and not the popularity of a mountain deity in Crete. -

Favourableness and Connectivity of a Western Iberian Landscape for the Reintroduction of the Iconic Iberian Ibex Capra Pyrenaica

Favourableness and connectivity of a Western Iberian landscape for the reintroduction of the iconic Iberian ibex Capra pyrenaica R ITA T. TORRES,JOÃO C ARVALHO,EMMANUEL S ERRANO,WOUTER H ELMER P ELAYO A CEVEDO and C ARLOS F ONSECA Abstract Traditional land use practices declined through- Keywords Capra pyrenaica, environmental favourableness, out many of Europe’s rural landscapes during the th cen- graph theory, habitat connectivity, Iberian ibex, reintroduc- tury. Rewilding (i.e. restoring ecosystem functioning with tion, ungulate minimal human intervention) is being pursued in many areas, and restocking or reintroduction of key species is often part of the rewilding strategy. Such programmes re- Introduction quire ecological information about the target areas but this is not always available. Using the example of the an has shaped landscapes for centuries (Vos & Iberian ibex Capra pyrenaica within the Rewilding Europe Meekes, ). In the last decades socio-economic M framework we address the following questions: ( ) Are and lifestyle changes have driven a rural exodus and the there areas in Western Iberia that are environmentally fa- abandonment of land throughout many of Europe’s rural vourable for reintroduction of the species? ( ) If so, are landscapes (MacDonald et al., ; Höchtl et al., ). these areas well connected with each other? ( ) Which of In some cases sociocultural and economic problems have these areas favour the establishment and expansion of a vi- created new opportunities for conservation (Theil et al., ). able population -

The Aegean Chapter Viii the Decorative

H. J. Kantor - Plant Ornament in the Ancient Near East, Chapter VIII: The Decorative Flora of Crete and the Late Helladic Mainland SECTION II: THE AEGEAN CHAPTER VIII THE DECORATIVE FLORA OF CRETE AND THE LATE HELLADIC MAINLAND In the midst of the sea, on the long island of Crete, there dwelt a people, possessors of the fabulous Minoan culture, who are known to have had trade relations with Egypt, and with other Near-Eastern lands. Still farther away towards the north lies the Mainland of Greece, a region that proved itself to be a very hospitable host to the graft of Minoan culture. Before the close of the LH period the ceramic results of this union were to be spread over the Near East in great profusion and it becomes necessary to define the extent of Aegean influence on those traditions of Near-Eastern art that lie within the scope of our topic. Before this is possible a concise summary of the plant ornamentation of the Aegean must be presented.1 This background forms a necessary basis without which the reaction of Aegean plant design on the main development of our story, be it large or small, cannot be determined. 1 A great deal of interest and work has been devoted to the study of Minoan decorative art almost since the beginning of its discovery, and full advantage of this has been taken in the preparation of the present survey. The chief treatments of the subject are as follows: Edith H. Hall, The Decorative Art of Crete in the Bronze Age (Philadelphia, 1907); Ernst Reisinger, Kretische Vasenmalerei vom Kamares bis zum Palast-Stil (Leipzig, Berlin, 1912); Diederich Fimmen, Die Kretisch-Mykenische Kulture (Leipzig, Berlin, 1924), Alois Gotsmich, Entwicklungsgang der Kretischen Ornamentik, Wein, 1923); Frederich Matz, Frühkretische Siegel (Berlin, 1928), covering a much wider field than is indicated by the title; Georg Karo, Die Schachtgräber von Mykenai (Munchen, 1939). -

Status and Protection of Globally Threatened Species in the Caucasus

STATUS AND PROTECTION OF GLOBALLY THREATENED SPECIES IN THE CAUCASUS CEPF Biodiversity Investments in the Caucasus Hotspot 2004-2009 Edited by Nugzar Zazanashvili and David Mallon Tbilisi 2009 The contents of this book do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of CEPF, WWF, or their sponsoring organizations. Neither the CEPF, WWF nor any other entities thereof, assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, product or process disclosed in this book. Citation: Zazanashvili, N. and Mallon, D. (Editors) 2009. Status and Protection of Globally Threatened Species in the Caucasus. Tbilisi: CEPF, WWF. Contour Ltd., 232 pp. ISBN 978-9941-0-2203-6 Design and printing Contour Ltd. 8, Kargareteli st., 0164 Tbilisi, Georgia December 2009 The Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund (CEPF) is a joint initiative of l’Agence Française de Développement, Conservation International, the Global Environment Facility, the Government of Japan, the MacArthur Foundation and the World Bank. This book shows the effort of the Caucasus NGOs, experts, scientific institutions and governmental agencies for conserving globally threatened species in the Caucasus: CEPF investments in the region made it possible for the first time to carry out simultaneous assessments of species’ populations at national and regional scales, setting up strategies and developing action plans for their survival, as well as implementation of some urgent conservation measures. Contents Foreword 7 Acknowledgments 8 Introduction CEPF Investment in the Caucasus Hotspot A. W. Tordoff, N. Zazanashvili, M. Bitsadze, K. Manvelyan, E. Askerov, V. Krever, S. Kalem, B. Avcioglu, S. Galstyan and R. Mnatsekanov 9 The Caucasus Hotspot N. -

European Court of Human Rights Examines Living Conditions in Hotspots Moria, Pyli & Vial

This project has been supported by the European Programme for Integration and Migration (EPIM), a collaborative initiative of the Network of European Foundations (NEF). The sole responsibility for the project lies with the organiser(s) and the content may not necessarily reflect the positions of EPIM, NEF or EPIM’s Partner Foundations. For immediate release EUROPEAN COURT OF HUMAN RIGHTS EXAMINES LIVING CONDITIONS IN HOTSPOTS MORIA, PYLI & VIAL Chios, Kos & Lesvos, January 20, 2021 While the situation on the East Aegean islands received particular attention after the outbreak of the fire in Moria, it has subsided more recently. At the same time, living conditions on the islands continue to be catastrophic. People have little access to medical care, wash facilities, and proper shelter, and are regularly forced to sleep in tents that flood easily in the winter rains. Particularly vulnerable people are not exempt from these conditions. Even in times when the Covid-19 was and is on the verge of an outbreak in the camps, members of at-risk groups continue to live exposed to these conditions without protection. The European Court of Human Rights has now asked the Greek government questions regarding the treatment of a total of eight people, all of whom were living in one of the so-called EU hotspots and had pre-existing medical conditions or were particularly vulnerable. In total, the Court connected 8 cases involving Chios, Kos, Lesvos and Samos, i.e. 4 out of 5 EU hotspots. These cases therefore demonstrate the structural illegality and impossibility to implement the hotspot approach and border procedures in a way that does not violate human rights. -

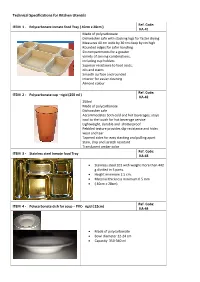

Technical Specifications for Kitchen Utensils

Technical Specifications for Kitchen Utensils Ref. Code: ITEM 1 - Polycarbonate inmate food Tray ( 40cm x 28cm ) KA-41 Made of polycarbonate Dishwasher safe with stacking lugs for faster drying Measures 40 cm wide by 30 cm deep by cm high Rounded edges for safer handling Six compartments for a greater variety of serving combinations, including cup holders Superior resistance to food acids, oils and stains Smooth surface and rounded interior for easier cleaning Almond colour Ref. Code: ITEM 2 - Polycarbonate cup –rigid (250 ml ) KA-42 250ml Made of polycarbonate Dishwasher safe Accommodates both cold and hot beverages; stays cool to the touch for hot beverage service Lightweight, durable and shatterproof Pebbled texture provides slip-resistance and hides wear and tear Tapered sides for easy stacking and pulling apart Stain, chip and scratch resistant Translucent amber color Ref. Code: ITEM 3 - Stainless steel Inmate food Tray KA-43 • Stainless steel 201 with weight more than 442 g divided in 5 parts. • Height minimum 2.5 cm. • Material thickness minimum 0.5 mm • ( 40cm x 28cm) Ref. Code: ITEM 4 - Polycarbonate dish for soup – PVC- rigid ( 22cm) KA-44 • Made of polycarbonate • Bowl diameter 22-24 cm • Capacity 350-360 ml Ref. Code: ITEM 5 - Plastic dish for salad – PVC- rigid KA-45 • Made of polycarbonate • Bowl diameter 22-24 cm • Capacity 225-250 ml ITEM 6- Heavy Duty Frying-pan from ( 2 set of 6 pcs from the biggest until Ref. Code: the smallest size) KA-46 Set of 6 Pcs from the biggest until the smallest size) Size fir the biggest one : 30-035 x 15-19.0-15 x 2.5 6.0 • Weight: 0.6-1.5 kg • Material: stainless steel Ref. -

Hydromechanism and Desalination of Coastal Karst Aquifers: Theory and Cases Hidromehanizem in Razslanitev Obalnih Kraških Vodonosnikov: Teorija in Primeri

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ZRC SAZU Publishing (Znanstvenoraziskovalni center - Slovenske akademije znanosti... COBISS: 1.01 HYDROMECHANISM AND DESALINATION OF COASTAL KARST AQUIFERS: THEORY AND CASES HIDROMEHANIZEM IN RAZSLANITEV OBALNIH KRAŠKIH VODONOSNIKOV: TEORIJA IN PRIMERI Marko BREZNIK1,2, & Franci STEINMAN1,3 Abstract UDC 556.114.5:627.8.034 Izvleček UDK 556.114.5:627.8.034 Marko Breznik & Franci Steinman: Hydromechanism and de- Marko Breznik & Franci Steinman: Hidromehanizem in razs- salination of coastal karst aquifers: Theory and Cases lanitev obalnih kraških vodonosnikov: Teorija in primeri Brackish water of coastal karst aquifers is useless. Desalination Somornica obalnih kraških vodonosnikov je neupora- methods are: interception method to capture fresh water in bna. Načini razslanjevanja so: prestrezanje sladke vode v karst massif, isolation and rise-spring-level methods to prevent kraški gmoti, izolacija vodonosnika in dvig gladine izvira za sea water inflow and reduced pumping of fresh water in dry preprečenje vtoka morske vode, ter zmanjšanje črpanja sladke periods. Four typical cases explain these methods. vode v sušnih obdobjih. Te načine pojasnjujejo štirje tipični Key words: coastal karst aquifers, desalination, methods, cases. primeri. Ključne besede: obalni kraški vodonosniki, razslanjevanje, načini, primeri. Introduction In the Ice ages were the differences between the scientists believe that the Azore islands’ anticyclone with lowest mean temperatures of the cold periods and the sunny weather has extended towards the Mediterranean. highest ones of the warm periods 5 degrees Celsius. Precipitations in the Portorož town have decreased by These differences between the lowest ones of the Ice ages 14%, during the last 50 years (Kajfež-Bogataj 2006).