Chapter 2 the EGYPTIAN SETTING

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Black and the Red

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-67598-7 - Ancient Egypt: An Introduction Salima Ikram Excerpt More information 1 The Black and the Red Geography and Environment The Greek historian and traveller Herodotus famously described Egypt as the gift of the Nile. Although this description was particularly true at the time of Herodotus’s visit to Egypt in the fi fth century BC , there was far more to the country’s prosperity than just the Nile River with its attendant annual fl oods. Egypt’s natural boundaries of deserts, seas, and boulder-strewn river rapids helped to protect the country from invaders and allowed its cul- ture to fl ourish in relative security. Its geographic loca- tion as a crossroads between Africa and Asia, where it served as a cultural and economic bridge between the two contin ents, made it an important entrepôt. Ideas, objects, and people travelled across Egypt, providing its people with a rich material and cultural life. Its borders on the Mediterranean Sea to the north and the Red Sea to the east offered access, respectively, to Europe, the Levant, Arabia, and India. Egypt’s geographic location played a critical role in its social, cultural, and economic develop- ment, as well as in its interaction with other areas of the ancient world, and contributed to its diverse history and heterogeneous population. Of all the ancient cultures, 1 © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-67598-7 - Ancient Egypt: An Introduction Salima Ikram Excerpt More information Egypt is perhaps unique in having maintained roughly the same boundaries throughout its history. -

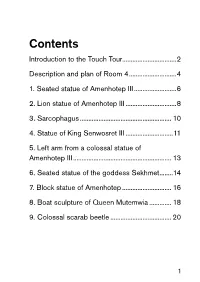

Contents Introduction to the Touch Tour

Contents Introduction to the Touch Tour................................2 Description and plan of Room 4 ............................4 1. Seated statue of Amenhotep III .........................6 2. Lion statue of Amenhotep III ..............................8 3. Sarcophagus ...................................................... 10 4. Statue of King Senwosret III ............................11 5. Left arm from a colossal statue of Amenhotep III .......................................................... 13 6. Seated statue of the goddess Sekhmet ........14 7. Block statue of Amenhotep ............................. 16 8. Boat sculpture of Queen Mutemwia ............. 18 9. Colossal scarab beetle .................................... 20 1 Introduction to the Touch Tour This tour of the Egyptian Sculpture Gallery is a specially designed Touch Tour for visitors with sight difficulties. This guide gives you information about nine highlight objects in Room 4 that you are able to explore by touch. The Touch Tour is also available to download as an audio guide from the Museum’s website: britishmuseum.org/egyptiantouchtour If you require assistance, please ask the staff on the Information Desk in the Great Court to accompany you to the start of the tour. The sculptures are arranged broadly chronologically, and if you follow the tour sequentially, you will work your way gradually from one end of the gallery to the other moving through time. Each sculpture on your tour has a Touch Tour symbol beside it and a number. 2 Some of the sculptures are very large so it may be possible only to feel part of them and/or you may have to move around the sculpture to feel more of it. If you have any questions or problems, do not hesitate to ask a member of staff. -

Encyclopaedism in the Mamluk Period: the Composition of Shihāb Al-Dīn Al-Nuwayrī’S (D

Encyclopaedism in the Mamluk Period: The Composition of Shihāb al-Dīn al-Nuwayrī’s (D. 1333) Nihāyat al-Arab fī Funūn al-Adab The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Muhanna, Elias Ibrahim. 2012. Encyclopaedism in the Mamluk Period: The Composition of Shihāb al-Dīn al-Nuwayrī’s (D. 1333) Nihāyat al-Arab fī Funūn al-Adab. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:9366551 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA © 2012 Elias Muhanna All rights reserved. Advisor: Professor Wolfhart P. Heinrichs Elias Muhanna Encyclopaedism in the Mamluk Period: The Composition of Shihāb al-Dīn al-Nuwayrī’s (d. 1333) Nihāyat al-arab fī funūn al-adab Abstract This dissertation explores the emergence of a golden age of Arabic encyclopaedic literature in the scholarly centers of Egypt and Syria during the Mamluk Empire (1250-1517). At the heart of the project is a study of Shihāb al-Dīn Aḥmad b. ʿAbd al-Wahhāb al-Nuwayrī’s (d. 1333) Nihāyat al-arab fī funūn al-adab (‘The Ultimate Ambition in the Branches of Erudition’), a 31-volume encyclopaedic work composed at the beginning of the 14th century and divided into five parts: (i) heaven and earth; (ii) the human being; (iii) animals; (iv) plants; and (v) the history of the world. -

Egyptian and Greek Water Cultures and Hydro-Technologies in Ancient Times

sustainability Review Egyptian and Greek Water Cultures and Hydro-Technologies in Ancient Times Abdelkader T. Ahmed 1,2,* , Fatma El Gohary 3, Vasileios A. Tzanakakis 4 and Andreas N. Angelakis 5,6 1 Civil Engineering Department, Faculty of Engineering, Aswan University, Aswan 81542, Egypt 2 Civil Engineering Department, Faculty of Engineering, Islamic University, Madinah 42351, Saudi Arabia 3 Water Pollution Research Department, National Research Centre, Cairo 12622, Egypt; [email protected] 4 Department of Agriculture, School of Agricultural Science, Hellenic Mediterranean University, Iraklion, 71410 Crete, Greece; [email protected] 5 HAO-Demeter, Agricultural Research Institution of Crete, 71300 Iraklion, Greece; [email protected] 6 Union of Water Supply and Sewerage Enterprises, 41222 Larissa, Greece * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 2 October 2020; Accepted: 19 November 2020; Published: 23 November 2020 Abstract: Egyptian and Greek ancient civilizations prevailed in eastern Mediterranean since prehistoric times. The Egyptian civilization is thought to have been begun in about 3150 BC until 31 BC. For the ancient Greek civilization, it started in the period of Minoan (ca. 3200 BC) up to the ending of the Hellenistic era. There are various parallels and dissimilarities between both civilizations. They co-existed during a certain timeframe (from ca. 2000 to ca. 146 BC); however, they were in two different geographic areas. Both civilizations were massive traders, subsequently, they deeply influenced the regional civilizations which have developed in that region. Various scientific and technological principles were established by both civilizations through their long histories. Water management was one of these major technologies. Accordingly, they have significantly influenced the ancient world’s hydro-technologies. -

Early Hydraulic Civilization in Egypt Oi.Uchicago.Edu

oi.uchicago.edu Early Hydraulic Civilization in Egypt oi.uchicago.edu PREHISTORIC ARCHEOLOGY AND ECOLOGY A Series Edited by Karl W. Butzer and Leslie G. Freeman oi.uchicago.edu Karl W.Butzer Early Hydraulic Civilization in Egypt A Study in Cultural Ecology Internet publication of this work was made possible with the generous support of Misty and Lewis Gruber The University of Chicago Press Chicago and London oi.uchicago.edu Karl Butzer is professor of anthropology and geography at the University of Chicago. He is a member of Chicago's Committee on African Studies and Committee on Evolutionary Biology. He also is editor of the Prehistoric Archeology and Ecology series and the author of numerous publications, including Environment and Archeology, Quaternary Stratigraphy and Climate in the Near East, Desert and River in Nubia, and Geomorphology from the Earth. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637 The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London ® 1976 by The University of Chicago All rights reserved. Published 1976 Printed in the United States of America 80 79 78 77 76 987654321 Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Butzer, Karl W. Early hydraulic civilization in Egypt. (Prehistoric archeology and ecology) Bibliography: p. 1. Egypt--Civilization--To 332 B. C. 2. Human ecology--Egypt. 3. Irrigation=-Egypt--History. I. Title. II. Series. DT61.B97 333.9'13'0932 75-36398 ISBN 0-226-08634-8 ISBN 0-226-08635-6 pbk. iv oi.uchicago.edu For INA oi.uchicago.edu oi.uchicago.edu CONTENTS List of Illustrations Viii List of Tables ix Foreword xi Preface xiii 1. -

Nation-Building and Childhood in Early Twentieth Century Egypt1

chapter 3 Nation-Building and Childhood in Early Twentieth Century Egypt1 Heidi Morrison Introduction In her autobiography, the Egyptian activist and writer Latifa Zayyat (1923–1996) recalls standing on the balcony of her home at 11 years of age and seeing the police shoot down 24 demonstrators. This was in 1934, when the Prime Minister, who served the King and the British Occupation, shut down all trains so that the leader of the majority Wafq party would not be able to tour the provinces. A procession of cars and thousands of people swarmed the streets. The municipality of the province ordered the digging of a series of trenches to prevent the demonstration from advancing. As Zayyat stood on the balcony, she counted the fallen bodies, observing guts exploding and deep red blood flowing like a waterfall. She noted one man raped by the policemen, while hearing her mother in the house cry.2 Writing many years later, Zayyat reflects on how she felt as a child watching the demonstration: I find no refuge from the sense of powerlessness, of distress, or oppres- sion that shakes me as the police shoot down twenty-four demonstrators that day, as I scream at my inability to do anything, to go down into the street and stop the bullets flying from the black guns.3 Although Zayyat saw herself as a helpless child in this moment of intense his- toric change, her life, and that of peers, was in reality at the heart of the Egyptian nationalist movement at the turn of the twentieth century. -

Photographs Covering Western Desert, Eastern Desert, Sinai Peninsula, Nile Region

Appendix: Photographs Covering Western Desert, Eastern Desert, Sinai Peninsula, Nile Region A. Western Desert Photo A.1 A community dominated by the psammophyte Ammophila arenaria inhabiting the coastal sand dunes of the Western Mediterranean Coast, Egypt 375 376 Appendix Photo A.2 Salt marsh vegetation with abundant growth of Kochia indica (Bassia indica) in the foreground. Mixed halophytes of Juncus rigidus and Arthrocnemum macrostachyum in the background, Western Mediterranean Coast, Egypt Photo A.3 Dense growth of Juncus rigidus in the salt marshes of Siwa Oasis, Western Desert, Egypt Appendix 377 Photo A.4 Reed swamp vegetation dominated by Typha domingensis, Siwa Oasis, Western Desert, Egypt 378 Appendix Photo A.5 A Populus euphratica tree inhabiting a sand dune in Siwa Oasis, Western Desert, Egypt. A clump of Stipagrostis scoparia is seen in the foreground Appendix 379 Photo A.6 Dense stand dominated by Typha elephantina, Um Rishe Lake, Wadi El-Natrun Depression, Western Desert, Egypt Photo A.7 A close up view of the succulent xerophyte Zygophyllum coccineum, Cairo-Alexandria desert road, Western Desert, Egypt 380 Appendix Photo A.8 Pancratium sickenbergeri bulbous herb, Mariut Plateau, northern section of the Western Desert, Egypt Photo A.9 Close-up view of the annual herb Asphodelus tenuifolius growing in the Western Mediterranean Coast, northern section of the Western Desert, Egypt Appendix 381 B. Eastern Desert Photo A.10 Mangal vegetation dominated by Avicennia marina, Red Sea Coast, Egypt Photo A.11 Dense mangrove forest dominated by Rhizophora mucronata, Southern section of the Red Sea Coast, Egypt 382 Appendix Photo A.12 A close up view of Rhizophora mucronata mangrove tree, Shalateen swamps, southern section of the Red Sea Coast, Egypt Photo A.13 Mangrove swamp of Rhizophora mucronata with a seedling in the forgroung, Mersa Abu Fissi, Red Sea Coast, Egypt Appendix 383 Photo A.14 A general view of the mangrove forest lining the shore-line of Mersa Abu Fissi, Red Sea coast, Egypt. -

Agriculture in Egypt from Pharaonic to Modern Times

I 1 Agriculture in Egypt from Pharaonic to Modern Times ALAN K. BOWMAN AND EUGENE ROGAN Land, Resources, Population EVEN IN THE EARLIEST Written records, Egypt was an ancient land. It was so for Herodotus, whose Greece of the fifth century BCE was by comparison a new world, as it was for the Graeco-Roman geographer Strabo writing early in the first century of the common era. The antiquity of cultivation and prodigious fertility cyclically renewed by the annual flood of the Nile, has given rise to the modern myth of ‘eternal Egypt’, as a timeless and unchanging land inhabited by a toiling and fatalistic peasantry. It is easy even in the 1990s to stand on the banks of the Nile, to observe the rectangular plots of land, the primitive methods of irrigation, the continued reliance on animal power and basic tools and to aver that agrarian life in Egypt has changed little since Pharaonic times. Were this the case, there would be little to interest scholars of different periods in reading a collection of essays on the agricultural organisation of Egypt. This is not our view. For us -to paraphrase Braudel’s encapsulation of the longue dur& in the Mediterranean-the Nile speaks with many voices; it is a sum of individual histories. As diverse as the voices of the inhabitants who have lived out Egypt’s history, the rural history of Egypt is one of dynamism and change, united by geography and the basic factors of production: land, water, labour, tools and seed. The geography of Egypt is the fundamental unifying factor of agricultural his- tory, though obviously not in itself unchanging. -

1 Egyptian Culture 2 Geography of Egypt 3 4 the Gift of the Nile 5

1 Egyptian Culture 2 Geography of Egypt Nile River is the longest river in the world The Nile creates a ribbon of water in a parched desert 3 4 The Gift of the Nile The predictable flooding of the Nile creates rich soil good for crops The Nile provides a reliable transportation system that promotes trade The desert acted as a natural barrier 5 Environmental Challenges if floods were a few feet below normal 1000’s of ppl starved if floods were higher than normal homes were destroyed desert acted as a natural barrier, but caused Egyptians to live on a small area and have little contact with others, did not have to deal with the constant attacks like the Fertile Crescent. 6 Upper and Lower Egypt Egyptians traveled along the Nile from the mouth to the First Cataract: churning rapids, the cataract area made it impossible to travel to the North past that pt Between the 1st Cataract and the Mediterranean lay 2 different regions Because of its elevation being higher the river area to the South is called Upper Egypt, it is the skinny strip of land from the 1st Cataract to the point where the river starts to fan out into many branches 7 Upper Egypt 8 Upper and Lower Egypt To the North, near the sea, Lower Egypt includes the Nile delta: the 100 miles before the river enters the Mediterranean. The delta is a broad marshy, triangular area of land formed by deposits of silt at the mouth of the river 9 Lower Egypt 10 Egypt unites into a Kingdom 10 Egypt unites into a Kingdom by 3200 BC the villages of Egypt were under the rule of two separate kingdoms, Lower Egypt and Upper Egypt it is believed that a ruler named Scorpion King started uniting Egypt, but it was finished by Narmer Narmer created a combination crown to represent his rule 11 Crowns 12 Pharaohs Rule as Gods In Mesopotamia kings were considered to be representatives of the gods. -

The Birth of Moses

1. THE BIRTH OF MOSES We arrived at Cairo International Airport just after nightfall. Though weary from a day of flying, we were excited to finally set foot on Egyptian soil and to catch a glimpse, by night, of the Great Pyramid of Giza. It took an hour and fifteen minutes to drive from the airport, on the northeast side of Cairo, to Giza, a southern suburb of the city. Even at night the streets were congested with the swelling population of twenty million people who live in greater Cairo. Upon checking into my hotel room, I opened the sliding door to my balcony, and stood for a moment, in awe, as I looked across at the pyramids by night. I was gazing upon the same pyramids that pharaohs, patriarchs, and emperors throughout history had stood before. It was a breathtaking sight. Copyright © by Abingdon21 Press. All rights reserved. 9781501807886_INT_Layout.indd 21 3/10/17 9:00 AM Moses The Pyramids and the Power of the Pharaohs Some mistakenly assume that these pyramids were built by the Israelite slaves whom Moses would lead to freedom, but the pyramids were already ancient when Israel was born. They had been standing for at least a thousand years by the time Moses came on the scene. So, if the Israelites were not involved in the building of these structures, why would we begin our journey—and this book—with the pyramids? One reason is simply that you should never visit Egypt without seeing the pyramids. More importantly, though, we begin with the pyramids because they help us understand the pharaohs and the role they played in Egyptian society. -

Pyramids on the Nile

2 Pyramids on the Nile MAIN IDEA WHY IT MATTERS NOW TERMS & NAMES SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY Many of the monuments built • delta • pyramid Using mathematical knowledge by the Egyptians stand as a •Narmer •mummification and engineering skills, Egyptians testament to their ancient • pharaoh •hieroglyphics built magnificent monuments to civilization. • theocracy • papyrus honor dead rulers. SETTING THE STAGE To the west of the Fertile Crescent in Africa, another river makes its way to the sea. While Sumerian civilization was on the rise, a sim- ilar process took place along the banks of this river, the Nile in Egypt. Yet the Egyptian civilization turned out to be very different from the collection of city-states in Mesopotamia. Early on, Egypt was united into a single kingdom, which allowed it to enjoy a high degree of unity, stability, and cultural continu- ity over a period of 3,000 years. The Geography of Egypt TAKING NOTES Summarizing Use a web From the highlands of East Africa to the Mediterranean Sea, the Nile River flows diagram to summarize northward across Africa for over 4,100 miles, making it the longest river in the Egyptian achievements. world. (See the map on page 36.) A thin ribbon of water in a parched desert land, the great river brings its water to Egypt from distant mountains, plateaus, and lakes in present-day Burundi, Tanzania, Uganda, and Ethiopia. Egypt’s settlements arose along the Nile on a narrow strip of land made fer- Eggyptian tile by the river. The change from fertile soil to desert—from the Black Land to Achievements the Red Land—was so abrupt that a person could stand with one foot in each. -

The Politics of Place in the Works of Ibn Taymīyah and Ibn Faḍl Allāh Al-ʿumarī

Trinity College Trinity College Digital Repository Faculty Scholarship 2015 The Politics of Place in the Works of Ibn Taymīyah and Ibn Faḍl Allāh al-ʿUmarī Zayde Antrim Trinity College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/facpub Part of the Near and Middle Eastern Studies Commons The Politics of Place in the Works of Ibn Taymīyah and Ibn Faḍl Allāh al-ʿUmarī ZZayd ZZayde Zayde Antrim Trinity College The Politics of Place in the Works of Ibn Taymīyah and Ibn Faḍl Allāh al-ʿUmarī It is well known that from its inception Arabic geographical writing was linked to political power. Among the earliest geographers in the Islamic world were career administrators for the Abbasid regime, and their works reflected—and at The Politics of Place times facilitated—the monitoring, taxation, and general control of an empire. 1 This role of geographer-administrator continued well into the Mamluk period, and one of the two individuals whose writing will be analyzed below, Ibn Faḍl Allāh al-ʿUmarī, fits easily into this category. However, other kinds of writing were devoted to representations of territory, sometimes in ways that were not so directly connected to political power or that were meant to challenge such power. Even though the notable religious scholar Ibn Taymīyah is not usually associated with geography, some of his works explicitly invoke the geographical imagina- tion in order to exhort political leaders or question their authority. In this article, I argue that the representation of territory was a useful strategy for promoting particular agendas, adopted equally by scholars of such contrasting orientations and backgrounds as Ibn Taymīyah and Ibn Faḍl Allāh al-ʿUmarī.