Dam Removal and Historic Preservation: Reconciling Dual Objectives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Proposed Regulation

REVISED 12/16 INDEØTg%ORV Regulatory Analysis Form (Completed by PromulgatingAgency) Wfl[: >ic (All Comments submitted on this regulation will appear on IRRC’s website) Mt. — 4 (1) Agency I Environmental Protection Thdepenqp Rf&uIt -Ui, Review r,.qu; (2) Agency Number: 7 Identification Number: 548 IRRC Number: (3) PA Code Cite: 25 Pa. Code Chapter 93 (4) Short Title: Water Quality Standards — Class A Stream Redesignations (5) Agency Contacts (List Telephone Number and Email Address): Primary Contact: Laura Edinger; 717.783.8727; ledingerpa.gov Secondary Contact: Jessica Shirley; 717.783.8727; jesshirleypa.gov (6) Type of Rulemaking (check applicable box): Proposed Regulation El Emergency Certification Regulation El Final Regulation El Certification by the Governor El Final Omitted Regulation El Certification by the Attorney General (7) Briefly explain the regulation in clear and nontechnical language. (100 words or less) The amendments to Chapter 93 reflect the list of recommended redesignations of streams as embedded in the attached Water Quality Standards Review Stream Redesignation Evaluation Report. The proposed regulation will update and revise stream use designations in 25 Pa. Code § 93.9d, 93.9f, 93.9j, 93.9k, 93.91, 93.9m, 93.9p, 93.9q, 93.9r, and 93.9t. These changes will not impose any new operating requirements on existing wastewater discharges or other existing activities regulated by the Department under existing permits or approvals. If a new, increased or additional discharge is proposed by a permit applicant, more stringent treatment requirements and enhanced best management practices (BMPs) may be necessary to maintain and protect the existing quality of those waters. -

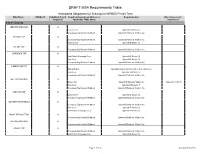

DRAFT MS4 Requirements Table

DRAFT MS4 Requirements Table Anticipated Obligations for Subsequent NPDES Permit Term MS4 Name NPDES ID Individual Permit Impaired Downstream Waters or Requirement(s) Other Cause(s) of Required? Applicable TMDL Name Impairment Adams County ABBOTTSTOWN BORO No Beaver Creek Appendix E-Siltation (5) Chesapeake Bay Nutrients/Sediment Appendix D-Nutrients, Siltation (4a) BERWICK TWP No Chesapeake Bay Nutrients/Sediment Appendix D-Nutrients, Siltation (4a) Beaver Creek Appendix E-Siltation (5) BUTLER TWP No Chesapeake Bay Nutrients/Sediment Appendix D-Nutrients, Siltation (4a) CONEWAGO TWP No South Branch Conewago Creek Appendix E-Siltation (5) Plum Creek Appendix E-Siltation (5) Chesapeake Bay Nutrients/Sediment Appendix D-Nutrients, Siltation (4a) CUMBERLAND TWP No Willoughby Run Appendix E-Organic Enrichment/Low D.O., Siltation (5) Rock Creek Appendix E-Nutrients (5) Chesapeake Bay Nutrients/Sediment Appendix D-Nutrients, Siltation (4a) GETTYSBURG BORO No Stevens Run Appendix E-Nutrients, Siltation (5) Unknown Toxicity (5) Rock Creek Appendix E-Nutrients (5) Chesapeake Bay Nutrients/Sediment Appendix D-Nutrients, Siltation (4a) HAMILTON TWP No Beaver Creek Appendix E-Siltation (5) Chesapeake Bay Nutrients/Sediment Appendix D-Nutrients, Siltation (4a) MCSHERRYSTOWN BORO No Chesapeake Bay Nutrients/Sediment Appendix D-Nutrients, Siltation (4a) Plum Creek Appendix E-Siltation (5) South Branch Conewago Creek Appendix E-Siltation (5) MOUNT PLEASANT TWP No Chesapeake Bay Nutrients/Sediment Appendix D-Nutrients, Siltation (4a) NEW OXFORD BORO No -

Water Company

VOLUME 2 PENNSYLVANIA-AMERICAN WATER COMPANY 2020 GENERAL BASE RATE CASE R-2020-3019369 (WATER) R-2020-3019371 (WASTEWATER) SCOPE OF OPERATIONS SCOPE OF OPERATIONS TABLE OF CONTENTS Page No. Water Abington 2 Bangor 5 Berry Hollow 7 Berwick 8 Boggs 9 Brownell/Fallbrook 10 Brownsville 12 Butler 14 Ceasetown/Watres 18 Clarion 22 Coatesville 24 Connellsville 26 Crystal Lake 27 Ellwood 29 Forest City 31 Frackville 33 Glen Alsace 35 Hershey 39 Hillcrest 42 Homesite 43 Indian Rocks 44 Indiana 45 Kane 47 Kittanning 48 Lake Heritage 49 Laurel Ridge 50 Lehman Pike 51 McEwensville Water 63 Milton 64 Mon-Valley 69 Moshannon Valley 70 Nazareth/Blue Mountain 72 Nesbitt/Huntville 75 New Castle 79 Nittany 82 Norristown 83 Olwen Heights 87 Penn Water 88 SCOPE OF OPERATIONS TABLE OF CONTENTS Page No. Pittsburgh 90 Pocono 94 Pocono Mt. Lake Forest Community Assoc. 96 Punxsutawney 97 Royersford 99 Scott Township 102 Scranton/Chinchilla 103 Steelton 107 Susquehanna 109 Sutton Hills 111 Turbotbille 112 Uniontown 113 Warren 115 Washington 116 West Shore 118 Yardley 122 Wastewater Blue Mountain Lake WW 128 Clarion WW 132 Claysville WW 134 Coatesville WW 135 Dravosburg WW 138 Duquesne WW 140 Exeter WW 142 Fairview WW 144 Franklin/Hamiltonban WW 145 Kane WW 146 Koppel WW 147 Lehman Pike WW 148 Marcel Lakes WW 153 McEwensville WW 154 McKeesport WW 155 New Cumberland WW 158 Paint Elk WW 159 Pocono WW 160 Scranton WW 164 Turbotville WW 169 WATER 1 Pennsylvania-American Water Company ABINGTON Pennsylvania American Water Company’s Abington district provides water service to approximately 6,458 customers throughout the Boroughs of Clarks Summit, Clarks Green and Dalton; and portions of Waverly, South Abington, North Abington, Scott, and Glenburn and Newton Townships. -

Annex a TITLE 25. ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION PART I

Annex A TITLE 25. ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION PART I. DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION Subpart C. PROTECTION OF NATURAL RESOURCES ARTICLE II. WATER RESOURCES CHAPTER 93. WATER QUALITY STANDARDS DESIGNATED WATER USES AND WATER QUALITY CRITERIA Editor’s Note: Additional changes to drainage list 93.9d were proposed on October 21, 2017 in the Pennsylvania Bulletin (47 Pa.B. 6609), including a stream name correction from “Beaverdam Run” to “Beaver Run.” § 93.9d. Drainage List D. Delaware River Basin in Pennsylvania Lehigh River Stream Zone County Water Uses Exceptions Protected to Specific Criteria * * * * * * 2—Lehigh River Main Stem, PA 903 Lehigh TSF, MF None Bridge to Allentown Dam 3—[Unnamed Basins, PA 903 Carbon[- CWF, MF None Tributaries] UNTs to Bridge to [Allentown Lehigh] Lehigh River Dam] UNT 03913 at 40°48'11.1"N; 75°40'20.6"W 3—Silkmill Run Basin Carbon CWF, MF None 3—Mauch Chunk Basin, Source to SR Carbon EV, MF None Creek 902 Bridge 3—Mauch Chunk Basin, SR 902 Bridge Carbon CWF, MF None Creek to Mouth 1 3—Beaverdam Run Basin Carbon HQ-CWF, None MF 3—Long Run Basin Carbon CWF, MF None Basin, Source to [Carbon] 3—Mahoning Creek CWF, MF None Wash Creek Schuylkill HQ-CWF, 4—Wash Creek Basin Schuylkill None MF Basin, Wash Creek to UNT 04074 at 3—Mahoning Creek Schuylkill CWF, MF None 40°46'43.4"N; 75°50'35.2"W HQ-CWF, 4—UNT 04074 Basin Schuylkill None MF Basin, UNT 04074 3—Mahoning Creek Carbon CWF, MF None to Mouth Basin, Source to SR 3—Pohopoco Creek 3016 Bridge at Monroe CWF, MF None Merwinsburg Main Stem, SR 3016 Bridge to -

Lackawanna River Tributaries Study/Plan

Cheryl Nolan 2013 COLDWATER Watershed Specialist Lackawanna County Conservation District HERITAGE PARTNERSHIP GRANT LACKAWANNA RIVER TRIBUTARIES STUDY/PLAN Coldwater Heritage Partnership Grant Final Report June 25, 2014 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Abstract .................................................................................................................................................. 2 II. Methodology .......................................................................................................................................... 5 III. Results .................................................................................................................................................... 5 A. Chemistry ............................................................................................................................................... 5 1. Equipment .......................................................................................................................................... 5 2. Results Summary ............................................................................................................................... 5 B. Benthic Macroinvertebrates ................................................................................................................. 7 C. Fish Population – Leggetts Creek (see Appendix A for complete report) .......................................... 9 D. Habitat Assessment (see Appendix B for complete assessment) ...................................................... -

Lackawanna River Watershed Conservation Plan

Lackawanna River Watershed Conservation Plan prepared by The Lackawanna River Corridor Association November 2001 This project is funded with support from the Chesapeake Bay Program Small Watershed Grants Program administered by the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation, the Scranton Area Foundation, the Rivers Conservation Program of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, Department of Conservation and Natural Resources and The membership and community support funding received through contributions to the Lackawanna River Corridor Association. This document has been prepared by: Bernard McGurl, Executive Director For the: Arthur Popp, Project Manager Deilsie Heath Kulesa, Administrative Assistant Gail Puente, Education and Outreach Coordinator Table of Contents 1. Introduction 1.1. Executive Summary: Issues, Process 1.2. Executive Plan Recommendations 1.3. Priority Recommendations 1.4. Considerations for Implementation 2. Purpose and Vision 2.1 Vision 2.2 Scope of Work 3. The River and Its Watershed 3.1 Soils and Geology 3.2 Flora and Fauna 3.3 Socio-economics and Cultural History 4. Issues: A discussion and review of public policy issues and topics affecting the Lackawanna River Watershed Environment 4.1 A discussion and review of public policy issues and topics affecting the Lackawanna River Watershed environment 5. Water Quality and Quantity 5.1 Sewage Treatment, Treatment Plants, CSO’s, Act 537 Planning 5.2 Storm Water Management 5.3 Acid Mine Drainage/Abandoned Mine Reclamation 5.4 Erosion and Sedimentation 5.5 Water Supply 5.6 Aquatic Habitats and Fisheries 6. Land Stewardship 6.1 Flood Plain Management 6.2 Stream Encroachment 6.3 Riparian and Upland Forest and Forestry Management 6.4 Wetlands 6.5 Natural Areas and Open Space Management 6.6 Land Use Regulations and Watershed Best Management Practices 6.7 Reclamation and Economic Development 6.8 Litter, Illegal Dumping and Contaminated Sites 7. -

1 Annex a TITLE 25. ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION

Annex A TITLE 25. ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION PART I. DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION Subpart C. PROTECTION OF NATURAL RESOURCES ARTICLE II. WATER RESOURCES CHAPTER 93. WATER QUALITY STANDARDS DESIGNATED WATER USES AND WATER QUALITY CRITERIA § 93.9d. Drainage List D. Delaware River Basin in Pennsylvania Lehigh River Exceptions Water Uses Stream Zone County To Specific Protected Criteria 2—Lehigh River Main Stem, the point Lehigh TSF, MF None at 40° 52' 3.5" N; 75° 44' 9.3" W to Allentown Dam 3—[Unnamed Basins, the point at Carbon[- CWF, MF None Tributaries] UNTs 40° 52' 3.5" N; 75° Lehigh] to Lehigh River 44' 9.3" W to [Allentown Dam] UNT 03913 at 40°48`11.1"N; 75°40`20.6"W 3—Silkmill Run Basin Carbon CWF, MF None 3—Mauch Chunk Creek 5—White Bear Creek Basin, Source to SR Carbon EV, MF None 902 Bridge 5—White Bear Creek Basin, SR 902 Bridge Carbon CWF, MF None to inlet of Mauch Chunk Lake 4—Mauch Chunk Basin Carbon CWF, MF None Lake 3—Mauch Chunk Basin, Mauch Chunk Carbon CWF, MF None Creek Lake Dam to Mouth 1 3—Beaver Run Basin Carbon HQ-CWF, None MF 3—Long Run Basin Carbon CWF, MF None 3—Mahoning Creek Basin, Source to [Carbon] CWF, MF None Wash Creek Schuylkill 4—Wash Creek Basin Schuylkill HQ-CWF, None MF 3—Mahoning Creek Basin, Wash Creek Schuylkill CWF, MF None to UNT 04074 at 40°46`43.4"N; 75°50`35.2"W 4—UNT 04074 Basin Schuylkill HQ-CWF, None MF 3—Mahoning Creek Basin, UNT 04074 to Carbon CWF, MF None Mouth 3—Pohopoco Creek Basin, Source to SR Monroe CWF, MF None 3016 Bridge at Merwinsburg 3—Pohopoco Creek Main Stem, SR 3016 -

Pennsylvania Bulletin Volume 47 (2017) Repository

Pennsylvania Bulletin Volume 47 (2017) Repository 2-25-2017 February 25, 2017 (Pages 1115-1268) Pennsylvania Legislative Reference Bureau Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/pabulletin_2017 Recommended Citation Pennsylvania Legislative Reference Bureau, "February 25, 2017 (Pages 1115-1268)" (2017). Volume 47 (2017). 8. https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/pabulletin_2017/8 This February is brought to you for free and open access by the Pennsylvania Bulletin Repository at Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Volume 47 (2017) by an authorized administrator of Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. Volume 47 Number 8 Saturday, February 25, 2017 • Harrisburg, PA Pages 1115—1268 Agencies in this issue The Courts Department of Banking and Securities Department of Community and Economic Development Department of Environmental Protection Department of Health Department of Revenue Department of State Department of Transportation Environmental Hearing Board Environmental Quality Board Executive Board Health Care Cost Containment Council Insurance Department Pennsylvania Infrastructure Investment Authority Pennsylvania Public Utility Commission Philadelphia Regional Port Authority Public School Employees’ Retirement Board State Board of Nursing State Conservation Commission Detailed list of contents appears inside. Latest Pennsylvania Code Reporter (Master Transmittal Sheet): Pennsylvania Bulletin Pennsylvania -

MS4 Requirements Table (Municipal)

MS4 Requirements Table (Municipal) Anticipated Obligations for Subsequent NPDES Permit Term MS4 Name NPDES ID Individual Permit Reason Impaired Downstream Waters or Requirement(s) Other Cause(s) of Impairment Required? Applicable TMDL Name Adams County ABBOTTSTOWN BORO No Beaver Creek Appendix E-Siltation (5) Water/Flow Variability (4c) Chesapeake Bay Nutrients/Sediment Appendix D-Nutrients, Siltation (4a) BERWICK TWP No Chesapeake Bay Nutrients/Sediment Appendix D-Nutrients, Siltation (4a) Beaver Creek Appendix E-Siltation (5) Water/Flow Variability (4c) BUTLER TWP No Chesapeake Bay Nutrients/Sediment Appendix D-Nutrients, Siltation (4a) CONEWAGO TWP No South Branch Conewago Creek Appendix E-Siltation (5) Unnamed Tributaries to South Branch Other Habitat Alterations, Water/Flow Variability Conewago Creek (4c) Chesapeake Bay Nutrients/Sediment Appendix D-Nutrients, Siltation (4a) Plum Creek Appendix E-Siltation (5) CUMBERLAND TWP No Chesapeake Bay Nutrients/Sediment Appendix D-Nutrients, Siltation (4a) Rock Creek Appendix E-Nutrients (5) Unnamed Tributaries to Rock Creek Appendix E-Siltation (5) Water/Flow Variability (4c) Willoughby Run Appendix E-Organic Enrichment/Low D.O., Siltation (5) Other Habitat Alterations (4c) GETTYSBURG BORO No Rock Creek Appendix E-Nutrients (5) Stevens Run Appendix E-Nutrients, Siltation (5) Unknown Toxicity (5), Water/Flow Variability (4c) Chesapeake Bay Nutrients/Sediment Appendix D-Nutrients, Siltation (4a) Unnamed Tributaries to Rock Creek Appendix E-Siltation (5) Water/Flow Variability (4c) HAMILTON -

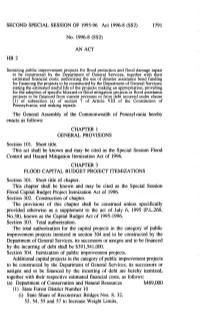

SECOND SPECIAL SESSION of 1995-96 Act 1996-8 (S52) 1791 No. 1996-8 (SS2) an ACT HB2 Enacts As Follows: Section 101. Short Title

SECOND SPECIAL SESSION OF 1995-96 Act 1996-8 (S52) 1791 No. 1996-8 (SS2) AN ACT HB2 Itemizing public improvement projects for flood protection and flood damage repair to be constructed by the Department of General Services, together with their estimated financial costs; authorizing the use of disaster assistance bond funding for financing the projectstobe constructed by the Department of General Services; stating the estimated useful life of the projects; making an appropriation;providing for the adoption of specific blizzard or flood mitigation projects or flood assistance projects to be financed from current revenues or from debt incurred under clause (1) of subsection (a) of section 7 of Article Viii of the Constitution of Pennsylvania; and making repeals. The General Assembly of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania hereby enacts as follows: CHAPTER 1 GENERAL PROVISIONS Section 101. Short title. This act shall be known and may be cited as the Special Session Flood Control and Hazard Mitigation Itemization Act of 1996. CHAPTER 3 FLOOD CAPITAL BUDGET PROJECT ITEMIZATIONS Section 301. Short title of chapter. This chapter shall be known and may be cited as the Special Session Flood Capital Budget Project Itemization Act of 1996. Section 302. Construction of chapter. The provisions of this chapter shall be construed unless specifically provided otherwise as a supplement to the act of July 6, 1995 (P1.269, No.38), known as the Capital Budget Act of 1995-1996. Section 303. Total authorization. The total authorization for the capital projects in the category of public improvement projects itemized in section 304 and to be constructed by the Department of General Services, its successors or assigns and to be financed by the incurring of debt shall be $391,541,000. -

Lackawanna River Watershed Conservation Plan

Lackawanna River Watershed Conservation Plan prepared by The Lackawanna River Corridor Association November 2001 This project is funded with support from the Chesapeake Bay Program Small Watershed Grants Program administered by the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation, the Scranton Area Foundation, the Rivers Conservation Program of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, Department of Conservation and Natural Resources and The membership and community support funding received through contributions to the Lackawanna River Corridor Association. This document has been prepared by: Bernard McGurl, Executive Director For the: Arthur Popp, Project Manager Deilsie Heath Kulesa, Administrative Assistant Gail Puente, Education and Outreach Coordinator Table of Contents 1. Introduction 1.1. Executive Summary: Issues, Process 1.2. Executive Plan Recommendations 1.3. Priority Recommendations 1.4. Considerations for Implementation 2. Purpose and Vision 2.1 Vision 2.2 Scope of Work 3. The River and Its Watershed 3.1 Soils and Geology 3.2 Flora and Fauna 3.3 Socio-economics and Cultural History 4. Issues: A discussion and review of public policy issues and topics affecting the Lackawanna River Watershed Environment 4.1 A discussion and review of public policy issues and topics affecting the Lackawanna River Watershed environment 5. Water Quality and Quantity 5.1 Sewage Treatment, Treatment Plants, CSO’s, Act 537 Planning 5.2 Storm Water Management 5.3 Acid Mine Drainage/Abandoned Mine Reclamation 5.4 Erosion and Sedimentation 5.5 Water Supply 5.6 Aquatic Habitats and Fisheries 6. Land Stewardship 6.1 Flood Plain Management 6.2 Stream Encroachment 6.3 Riparian and Upland Forest and Forestry Management 6.4 Wetlands 6.5 Natural Areas and Open Space Management 6.6 Land Use Regulations and Watershed Best Management Practices 6.7 Reclamation and Economic Development 6.8 Litter, Illegal Dumping and Contaminated Sites 7. -

A Publication of the Lackawanna River Corridor Association

Lackawanna River Watershed Atlas A publication of the Lackawanna River Corridor Association Lackawanna River Watershed Atlas Geographic Information Systems mapping in the watershed area of northeastern Pennsylvania in Lackawanna, Luzerne, Susquehanna, and Wayne counties. A publication of the Lackawanna River Corridor Association First Edition Copyright 2008 This publication made possible by a grant from the Margaret Briggs Foundation and by support from the membership of the Lackawanna River Corridor Association. Map and atlas design: Alexandra Serio Younica Acknowledgements This project was made possible by a grant from the Margaret Briggs Foundation. The Lackawanna River Corridor Association would like to thank the following organizations assisting with this project. Concurrent Technologies Corporation King’s College Lackawanna County Conservation District Lackawanna County GIS Luzerne County GIS Wayne County GIS Cover Graphic The watershed graphic is derived from a mosaic of the 10 meter digital elevation model United States Geological Survey Table of Contents Original drawings by Bernie McGurl The Lackawanna River Guide, 1994 Acronyms ……..…………………….. ii Mapping Details ……..…………………….. iii Introductory Overview ……..…………………….. 1 The Lackawanna River Basin and Adjacent Watersheds What is a Watershed? ……..…………………….. 3 Places ……..…………………….. 5 Geology & Industry ……..…………………….. 7 GIS for the Watershed ……..…………………….. 9 Land Use ……..…………………….. 11 People ……..…………………….. 13 The Water ……..…………………….. 15 Preserving the Watershed ……..…………………….. 17 The