Faculty of Graduate Faculty of Arts Studies in Partial for the Degree

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pdfs GST-HST Municipal Rebates 2019 E Not Finished.Xlsx

GST/HST Incremental Federal Rebate for Municipalities Report - January 1 to December 31, 2019 Manitoba PAYMENT LEGAL NAME CITY NAME FSA AMOUNT 2625360 MANITOBA ASSOCIATION INC. NEEPAWA R0J $2,993.73 285 PEMBINA INC WINNIPEG R2K $10,624.47 4508841 MANITOBA ASSOCIATION INC WINNIPEG R2K $517.02 474 HARGRAVE CORPORATION WINNIPEG R3A $2,504.76 6869166 MANITOBA LTD. SANFORD R0G $7,370.38 ACADEMY ROAD BUSINESS IMPROVMENT ZONE WINNIPEG R3N $1,389.15 AGASSIZ WEED CONTROL DISTRICT BEAUSEJOUR R0E $549.30 ALTONA RURAL WATER SERVICES CO-OP LTD ALTONA R0G $1,860.62 ARBORG BI-FROST PARKS & RECREATION COMMISSION ARBORG R0C $5,326.89 ARGYLE-LORNE-SOMERSET WEED CONTROL DISTRICT BALDUR R0K $553.10 ARLINGTONHAUS INC. WINNIPEG R2K $11,254.49 ARTEMIS HOUSING CO-OP LTD WINNIPEG R3A $2,784.09 ASTRA NON-PROFIT HOUSING CORPORATION WINNIPEG R2K $2,993.66 AUTUMN HOUSE INC. WINNIPEG R3E $3,532.89 B&G UTILITIES LTD BRANDON R7B $3,643.38 BAPTIST MISSION APARTMENTS INC. WINNIPEG R3E $2,224.34 BARROWS COMMUNITY COUNCIL BARROWS R0L $3,837.41 BEAUSEJOUR BROKENHEAD DEVELOPMENT CORP BEAUSEJOUR R0E $3,583.19 BETHANIAHAUS INC. WINNIPEG R2K $17,881.45 BIBLIOTHÉQUE MONTCALM LIBRARY SAINT-JEAN-BAPTISTE R0G $180.01 BIBLIOTHÉQUE REGIONALE JOLYS REGIONAL LIBRARY SAINT-PIERRE-JOLYS R0A $267.88 BIBLIOTHÉQUE TACHÉ LIBRARY LORETTE R0A $851.71 BISSETT COMMUNITY COUNCIL BISSETT R0E $2,919.53 BLUMENFELD HOCHFELD WATER CO-OP LTD WINKLER R6W $770.13 BLUMENORT SENIOR CITIZENS HOUSING INC. STEINBACH R5G $515.67 BOISSEVAIN - MORTON LIBRARY AND ARCHVIES BOISSEVAIN R0K $784.80 BOISSEVAIN AND MORTON -

Carte Des Zones Contrôlées Controlled Area

280 RY LAKE 391 MYSTE Nelson House Pukatawagan THOMPSON 6 375 Sherridon Oxford House Northern Manitoba ds River 394 Nord du GMo anitoba 393 Snow Lake Wabowden 392 6 0 25 50 75 100 395 398 FLIN FLON Kilometres/kilomètres Lynn Lake 291 397 Herb Lake 391 Gods Lake 373 South Indian Lake 396 392 10 Bakers Narrows Fox Mine Herb Lake Landing 493 Sherritt Junction 39 Cross Lake 290 39 6 Cranberry Portage Leaf Rapids 280 Gillam 596 374 39 Jenpeg 10 Wekusko Split Lake Simonhouse 280 391 Red Sucker Lake Cormorant Nelson House THOMPSON Wanless 287 6 6 373 Root Lake ST ST 10 WOODLANDS CKWOOD RO ANDREWS CLEMENTS Rossville 322 287 Waasagomach Ladywood 4 Norway House 9 Winnipeg and Area 508 n Hill Argyle 323 8 Garde 323 320 Island Lake WinnBRiOpKEeNHEgAD et ses environs St. Theresa Point 435 SELKIRK 0 5 10 15 20 East Selkirk 283 289 THE PAS 67 212 l Stonewall Kilometres/Kilomètres Cromwel Warren 9A 384 283 509 KELSEY 10 67 204 322 Moose Lake 230 Warren Landing 7 Freshford Tyndall 236 282 6 44 Stony Mountain 410 Lockport Garson ur 220 Beausejo 321 Westray Grosse Isle 321 9 WEST ST ROSSER PAUL 321 27 238 206 6 202 212 8 59 Hazelglen Cedar 204 EAST ST Cooks Creek PAUL 221 409 220 Lac SPRINGFIELD Rosser Birds Hill 213 Hazelridge 221 Winnipeg ST FRANÇOIS 101 XAVIER Oakbank Lake 334 101 60 10 190 Grand Rapids Big Black River 27 HEADINGLEY 207 St. François Xavier Overflowing River CARTIER 425 Dugald Eas 15 Vivian terville Anola 1 Dacotah WINNIPEG Headingley 206 327 241 12 Lake 6 Winnipegosis 427 Red Deer L ake 60 100 Denbeigh Point 334 Ostenfeld 424 Westgate 1 Barrows Powell Na Springstein 100 tional Mills E 3 TACH ONALD Baden MACD 77 MOUNTAIN 483 300 Oak Bluff Pelican Ra Lake pids Grande 2 Pointe 10 207 eviève Mafeking 6 Ste-Gen Lac Winnipeg 334 Lorette 200 59 Dufresne Winnipegosis 405 Bellsite Ile des Chênes 207 3 RITCHOT 330 STE ANNE 247 75 1 La Salle 206 12 Novra St. -

Mennonite Institutions

-being the Magazine/Journal of the Hanover Steinbach Historical Society Inc. Preservings $10.00 No. 18, June, 2001 “A people who have not the pride to record their own history will not long have the virtues to make their history worth recording; and no people who are indifferent to their past need hope to make their future great.” — Jan Gleysteen Mennonite Institutions The Mennonite people have always been richly Friesen (1782-1849), Ohrloff, Aeltester Heinrich portant essay on the historical and cultural origins endowed with gifted thinkers and writers. The Wiens (1800-72), Gnadenheim, and theologian of Mennonite institutions. The personal reflections seminal leaders in Reformation-times compiled Heinrich Balzer (1800-42) of Tiege, Molotschna, of Ted Friesen, Altona, who worked closely with treatises, polemics and learned discourses while continued in their footsteps, leaving a rich literary Francis during his decade long study, add a per- the martyrs wrote hymns, poetic elegies and in- corpus. sonal perspective to this important contribution to spirational epistles. During the second half of the The tradition was brought along to Manitoba the Mennonite people. The B. J. Hamm housebarn in the village of Neu-Bergthal, four miles southeast of Altona, West Reserve, Manitoba, as reproduced on the cover of the second edition of E. K. Francis, In Search of Utopia, republished by Crossway Publications Inc., Box 1960, Steinbach, Manitoba, R0A 2A0. The house was built in 1891 by Bernhard Klippenstein (1836-1910), village Schulze, and the barn dates to the founding of the village in 1879, and perhaps even earlier to the village of Bergthal in the East Reserve. -

3 a Forgotten Encounter 13 Reorienting the West Reserve 21

Mennonites on the Rails ISSUE NUMBER 39, 2019 3 A Forgotten 13 Reorienting 21 The Railroad Encounter the West Passes by The C.N.R.’s Community Reserve Steinbach Progress Competitions Mennonites and the Ralph Friesen James Urry Railway Hans Werner Contents ISSUE NUMBER 39, 2019 1 Notes from the Editor A JOURNAL OF THE D. F. PLETT HISTORICAL RESEARCH FOUNDATION, INC. Features EDITOR Aileen Friesen 3 A Forgotten COPY EDITOR Andrea Dyck Encounter DESIGNER Anikó Szabó James Urry PUBLICATION ADDRESS Plett Foundation 13 Reorienting the University of Winnipeg West Reserve 515 Portage Ave Hans Werner Winnipeg, Manitoba R3B 2E9 21 The Railroad Passes 3 EDITORIAL SUBMISSIONS by Steinbach Aileen Friesen Ralph Friesen +1 (204) 786 9352 [email protected] SUBSCRIPTIONS AND Research Articles ADDRESS CHANGES Andrea Dyck [email protected] 25 Mennonite Debt in the West Reserve Preservings is published semi-annually. Bruce Wiebe The suggested contribution to assist in covering the considerable costs of preparing this journal is $20.00 per year. 31 The Early Life 31 Cheques should be made out to the of Martin B. Fast D. F. Plett Historical Research Foundation. Katherine Peters Yamada MISSION To inform our readers about the history of 37 Klaas W. Brandt the Mennonites who came to Manitoba in the Dan Dyck 1870s and their descendants, and in particular to promote a respectful understanding and appreciation of the contributions made by so-called Low German-speaking conservative Histories & Reflections Mennonite groups of the Americas. Mennonite-Amish- 43 37 PLETT FOUNDATION Hutterite Migrations BOARD OF DIRECTORS John J. Friesen 2019–2020 Royden Loewen, Chair, Winnipeg, MB John J. -

Community MUNICIPALITY ABIGAIL MUNICIPALITY of BOISSEVAIN

Community MUNICIPALITY ABIGAIL MUNICIPALITY OF BOISSEVAIN-MORTON ADELPHA MUNICIPALITY OF BOISSEVAIN-MORTON AGHAMING INDIGENOUS AND NORTHERN RELATIONS AGNEW RM OF PIPESTONE AIKENS LAKE INDIGENOUS AND NORTHERN RELATIONS AKUDLIK TOWN OF CHURCHILL ALBERT RM OF ALEXANDER ALBERT BEACH RM OF VICTORIA BEACH ALCESTER MUNICIPALITY OF BOISSEVAIN-MORTON ALCOCK RM OF REYNOLDS ALEXANDER RM OF WHITEHEAD ALFRETTA HAMIOTA MUNICIPALITY ALGAR RM OF SIFTON ALLANLEA MUNICIPALITY OF GLENELLA-LANSDOWNE ALLEGRA RM OF LAC DU BONNET ALLOWAY RIVERDALE MUNICIPALITY ALMASIPPI RM OF DUFFERIN ALPHA RM OF PORTAGE LA PRAIRIE ALPINE MUNICIPALITY OF SWAN VALLEY WEST ALTAMONT MUNICIPALITY OF LORNE ALTBERGTHAL MUNICIPALITY OF RHINELAND AMANDA RM OF ALEXANDER AMARANTH RM OF ALONSA AMBER RM OF MINTO-ODANAH AMBROISE SETTLEMENT RM OF PORTAGE LA PRAIRIE AMERY Not within a MUNICIPALITY ANAMA BAY INDIGENOUS AND NORTHERN RELATIONS ANEDA RM OF LAC DU BONNET ANGUSVILLE RM OF RIDING MOUNTAIN WEST ANOLA RM OF SPRINGFIELD APISKO LAKE INDIGENOUS AND NORTHERN RELATIONS ARBAKKA RM OF STUARTBURN ARBOR ISLAND MUNICIPALITY OF BOISSEVAIN-MORTON ARDEN MUNICIPALITY OF GLENELLA-LANSDOWNE ARGEVILLE RM OF COLDWELL ARGUE MUNICIPALITY OF GRASSLAND ARGYLE RM OF ROCKWOOD ARIZONA MUNICIPALITY OF NORTH NORFOLK ARMSTRONG SIDING MUNICIPALITY OF WESTLAKE-GLADSTONE ARNAUD MUNICIPALITY OF EMERSON-FRANKLIN ARNES RM OF GIMLI Community MUNICIPALITY ARNOT INDIGENOUS AND NORTHERN RELATIONS ARONA RM OF PORTAGE LA PRAIRIE ARROW RIVER PRAIRIE VIEW MUNICIPALITY ASESSIPPI RM OF RIDING MOUNTAIN WEST ASHBURY RM OF WHITEHEAD -

Pdfs GST-HST Municipal Rebates 2018 E.Xlsx

GST/HST Incremental Federal Rebate for Municipalities Report - January 1 to December 31, 2018 Manitoba PAYMENT LEGAL NAME CITY NAME FSA AMOUNT 2625360 MANITOBA ASSOCIATION INC. NEEPAWA R0J $1,112.09 285 PEMBINA INC WINNIPEG R2K $11,916.31 4508841 MANITOBA ASSOCIATION INC WINNIPEG R2K $1,519.18 474 HARGRAVE CORPORATION WINNIPEG R3A $2,653.46 6869166 MANITOBA LTD. SANFORD R0G $6,712.69 7049651 MANITOBA ASSOCIATION INC. WINNIPEG R3B $330,332.94 ACADEMY ROAD BUSINESS IMPROVMENT ZONE WINNIPEG R3N $6,535.53 AGASSIZ WEED CONTROL DISTRICT BEAUSEJOUR R0E $244.81 ALTONA RURAL WATER SERVICES CO-OP LTD ALTONA R0G $2,145.25 ARBORG BI-FROST PARKS & RECREATION COMMISSION ARBORG R0C $4,415.00 ARGYLE-LORNE-SOMERSET WEED CONTROL DISTRICT BALDUR R0K $322.95 ARLINGTONHAUS INC. WINNIPEG R2K $6,353.08 ARTEMIS HOUSING CO-OP LTD WINNIPEG R3A $1,573.30 ASTRA NON-PROFIT HOUSING CORPORATION WINNIPEG R2K $2,548.64 AUTUMN HOUSE INC. WINNIPEG R3E $7,366.31 BAPTIST MISSION APARTMENTS INC. WINNIPEG R3E $3,828.08 BARROWS COMMUNITY COUNCIL BARROWS R0L $2,713.78 BEAUSEJOUR BROKENHEAD DEVELOPMENT CORP BEAUSEJOUR R0E $4,669.11 BETELSTADUR HOUSING COOPERATIVE LTD WINNIPEG R3A $669.10 BETHANIAHAUS INC. WINNIPEG R2K $6,160.12 BIBLIOTHÉQUE MONTCALM LIBRARY SAINT-JEAN-BAPTISTE R0G $177.01 BIBLIOTHÉQUE REGIONALE JOLYS REGIONAL LIBRARY SAINT-PIERRE-JOLYS R0A $761.21 BIBLIOTHÉQUE TACHÉ LIBRARY LORETTE R0A $729.46 BISSETT COMMUNITY COUNCIL BISSETT R0E $4,346.40 BLUMENFELD HOCHFELD WATER CO-OP LTD WINKLER R6W $540.72 BLUMENORT SENIOR CITIZENS HOUSING INC. STEINBACH R5G $834.10 BOISSEVAIN -

Brauns of Osterwick

The Brauns of Osterwick Mr. and Mrs. Jakob Braun FOREWORD The purpose of this writing has been to lift a small corner of the veil from the conditions under which the Jakob Braun family and their descendents have come during the past century. This has been accomplished quite inadequately. There are too many areas left unanswered. Three types of information have been employed for this purpose: I. genealogical tables; 2. brief biographical sketches; 3. editorial contributions from all who responded to the invitations. A liberal sprinkling of photographs has been added for emphasis. Information has been gleaned from the small number of family records, diaries, journals, documents, school registers, church records, newspapers and personal letters available. The passing of the first, the second and the oldest members of the third generations has greatly curtailed the information obtainable on the harrowing experiences, but now very interesting information, on the pioneering years. The paucity of such material may be due to numerous factors, the least of which would likely not be the hesitancy of people to do some writing. Moreover what was written, was too often not -preserved. This was regretfully demonstrated by the church secretary who consigned the old church register to the flames when a new one had to be purchased. Since whole families so frequently migrated from the old world to the new, there was likely less cause for letter-writing, removing an important reason for recording family joys and sorrows. More time and money for research may unearth further pertinent material on our family. If this present effort should produce that result it will not have been in vain. -

SG-62H -- Surficial Geology of the Winnipeg Map Sheet

ine ibo sin River As Meadows 7 26R iv R 4 W R e3 W R 2 W R 1 W R 1 E R 2 E R 3 E R 4 E R 5 E R 6 E R 7 E R 8 E R 9 E R 10 E R 11 E 98° r 96° 575,000 600,000 625,000 650,000 675,000 700,000 Rivercrest 50° 50° SURFICIAL GEOLOGY COMPILATION MAP SERIES 7 11 Rosser 8 Cloverleaf 6 101 East St. Paul West Pine Ridge 9 The Surficial Geology Compilation Map Series (SGCMS) addresses an increasing demand for St. Eustache 59 Middlechurch consistent surficial geology information for applications such as groundwater protection, Birds Hill Hazelridge Whitemouth industrial mineral management, protected lands, basic research, mineral exploration, 26 engineering, and environmental assessment. The SGCMS will provide province-wide coverage Oakbank at scales of 1:500 000, 1:250 000 and a final compilation at 1:1 000 000. 1 B 11 Fortier A r Tp 11 s o Tp 11 ke s n The unit polygons were digitized from paper maps originally published by the Geological h Oak in e ville a Survey of Canada and Manitoba Geological Survey (MGS). In several areas, digital polygons Benard ib d oSt. Francois Xavier derived from soils mapping were used to fill gaps in the geological mapping. The 1:250 000 13 in Elie e scale maps provide a bibliography for the original geological mapping. Dugald Glass Anola Vivian Edge-matching of adjoining 1:250 000 scale map sheets is based on data from the Shuttle 0 1 Winnipeg 1 0 15 Ste. -

Heritage Posting, No. 70

Heritage Posting 1 HERITAGE POSTING No. 70 November 2011 Wilhelm Peter Enns celebrated his 100th birthday as he cut the ribbon at the Museum opening. Winkler Heritage Museum Grand Opening by Alan Warkentin history and growth. The closing prayer of Menno Janzen The City of Winkler now has a museum to call its own. of the Bergthaler Church also echoed that. The Official Grand Opening of the Winkler Heritage A significant part of the opening ceremony was the ribbon-cutting which was done by Wilhelm Peter Enns, an Museum at its present location in the Southland Mall in th Winkler was held on August 3rd, 2011 at 10 AM. About area resident who was celebrating his 100 birthday that 150 people were in attendance. very day. Jerry Hildebrand, chair of the Winkler Heritage Society, The museum’s Mission Statement or purpose is to introduced the event and Arnie Neufeld, chair of the show “How to Build a Growing Prairie Community.” The Winkler Heritage Museum Committee, introduced some of various exhibits do that. the speakers. Speeches and congratulatory wishes were There are displays with items from early businesses, given by Candice Hoeppner (MP for Portage Lisgar), Peter books recounting the early history of Winkler (also relating G. Dyck (MLA for Pembina), Marvin Plett (Councillor City to the significance of the Jewish and German pioneers – of Winkler), Hans Werner (Author of Living between not only Mennonites), toys, musical instruments, Worlds: a History of Winkler), John Elias (Local Historian glassware, school items, household items, tools and much and Writer), and Don Kroeker (Winkler business man with more. -

Community Profile

COMMUNITY PROFILE REGION : Pembina Valley PO P ULATION (2006): 2662 PE R CENT OF P O P ULATION 65+: 12% MEDIAN AGE : 35.1 The Rural Municipality of Morris is located approximately 50 kilometres south- west of Winnipeg in the Pembina Valley Region of Manitoba. The communities that make up the municipality are Rosenort, Lowe Farm, Mctavish, Silver Plains, Kane, Aubigny, Sperling, Riverside, and Sewell. ANITOBA The RM of Morris thrives on two main industries, the agriculture industry and the steel manufacturing industry. Farmers in the area produce a variety of crops including wheat, flax, barley, strawberries, raspberries, and different types of , M vegetables. In addition, livestock production such as poultry and beef make up much of Manitoba’s market. The steel manufacturing industry mostly takes place in the Rosenort area and produces products such as grain augers, grain bins and truck boxes. It employs approximately 400 residents of the RM. The RM of Morris offers many recreational, sporting, and cultural activities for the communities of Lowe Farm, Sperling, Rosenort, Riverside, Aubigny, and Kane. In addition, the Morris River and the Red River in the RM serve as popu- lar fishing spots for local residents. (Adapted from: www. http://www.communityprofiles.mb.ca) MORRIS RM OF RU R AL MUNICIPALITY OF MO rr IS % OF TOTAL CHA R ACTE R ISTIC POPULATION Total Population (1, 2) 2662 Population change from 2001 (%) -2.2 Population density per square kilometre 2.6 GENDER Male 50.5% Female 49.5% AG E GROUP < 45 63.2% 45-54 14.4% 55-64 10.1% -

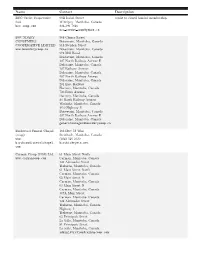

Name Contact Description BCC Credit Cooperative Ltd Bcc-Coop.Com 99B

Name Contact Description BCC Credit Cooperative 99B Isabel Street credit to closed bonded membership Ltd Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada bcc-coop.com 204-296 7846 bcc credit [email protected] BOUNDARY 564 Cherry Street CONSUMERS Boissevain, Manitoba, Canada COOPERATIVE LIMITED 518 Stephen Street www.boundarycoop.ca Boissevain, Manitoba, Canada 578 Mill Road Boissevain, Manitoba, Canada 407 North Railway Avenue E Deloraine, Manitoba, Canada 107 Railway Avenue Deloraine, Manitoba, Canada 407 North Railway Avenue Deloraine, Manitoba, Canada 201 East Railway Hartney, Manitoba, Canada 700 River Avenue Hartney, Manitoba, Canada 23 North Railway Avenue Waskada, Manitoba, Canada #10 Highway S Boissevain, Manitoba, Canada 407 North Railway Avenue E Deloraine, Manitoba, Canada [email protected] Birchwood Funeral Chapel 162 Hwy 52 West (coop) Steinbach, Manitoba, Canada www. (204) 346-1030 birchwoodfuneralchapel. [email protected] com Carman Co-op (1959) Ltd. 61 Main Street North www.carmancoop.com Carman, Manitoba, Canada 104 Alexander Street Treherne, Manitoba, Canada 61 Main Street North Carman, Manitoba, Canada 65 Main Street N Carman, Manitoba, Canada 63 Main Street N Carman, Manitoba, Canada 367A Main Street Carman, Manitoba, Canada 104 Alexander Street Treherne, Manitoba, Canada Highway 2 Treherne, Manitoba, Canada 63 Principale Street La Salle, Manitoba, Canada 51 Principale Street La Salle, Manitoba, Canada [email protected] 1 Name Contact Description Carman Co-op (1959) Ltd. 43A Main Street N (administrative office) Carman, Manitoba, Canada www.carmancoop.com 203 745 2073 [email protected] Crocus Trail Consumers 50025 Road 101N in early stages of development - created for the Co-op Ltd. Langruth, Manitoba, Canada purpose of a community restaurant, motel and po- 204 445 2236 tentially grocery store [email protected] Dauphin Consumers 18 3rd Avenue NE food, petroleum, c-stores, fertilizer, seed, chemi- Cooperative Ltd. -

Manitoba Landscape

Published in the interest o f the best in the religious, social, and economic phases o f Mennonite culture Bound Volumes Mennonite Life is available in a series of bound volumes as follows: 1. Volume M il (1946-48) $6 2. Volume IV-V (1949-50) $5 3. Volume VI-VII (1951-52) $5 4. Volume VIII-IX (1953-54) $5 If ordered directly from Mennonite Life all four volumes are available at $18. Back Issues Wanted! Our supply of the first issue of Mennonite Life, January 1946, and January 1948, is exhausted. We would appreciate it if you could send us your copies. For both copies we would extend your subscription for one year. Address all correspondence to MENNONITE LIFE North Newton, Kansas COVER Manitoba Landscape Photography by Gerhard Sawatzky MENNONITE LIFE An Illustrated Quarterly EDITOR Cornelius Krahn ASSISTANT TO THE EDITOR John F. Schmidt ASSOCIATE EDITORS Harold S. Bender S. F. Pannabecker J. Winfield Fretz Robert Kreider Melvin Gingerich J. G. Rempel N. van der Zijpp Vol. XI July, 1956 No. 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Contributors............................................................................................... ............................... 2 Russian Baptists and Mennonites............................................................. ...Cornelius Krahn 99 Else Krueger Pursues Art as a Hobby...................................................... ................................... 102 Manitoba Roundabout............................................................................... ........Victor Peters 104 Life in a Mennonite