Chapter Eighteen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Z-Nation - EP 2XX - FULL PINK (10/10/15) 2

EPISODE 200 "PEACE OF MURPHY" Written by REDACTED Directed by REDACTED PRODUCTION DRAFT 08/01/15 FULL BLUE 08/05/15 The Asylum Los Angeles 45315 FADE IN: 1 EXT. COUNTRY ROAD - DAY 1 We open on a desolate stretch of back-road. The mid-day sun beats down. There’s no noise. No crickets chirping. Like most places in this world: dead and way too quiet. A RUSTED BILLBOARD casts a shadow across the sweltering tarmac. A cartoon bear warning visitors that “ONLY YOU CAN PREVENT FOREST FIRES”. Behind the billboard, in the distance - AN ATOMIC FIRE RAVAGES THE LANDSCAPE. SLOW FOOTSTEPS break the silence. A WOUNDED-MAN drags himself down the road. Blackened and burned: The clothes are literally falling from his back. He’s sick and desperate - A victim of radiation poisoning. The Wounded-Man reaches the shadow of the billboard before stumbling - And collapsing to his knees. He looks towards the sky. Coughs. WOUNDED-MAN Please. Somebody... Anybody? ANGLE ON: A VEHICLE APPROACHING FROM THE DISTANCE The man smiles, his prayers have been answered. WOUNDED-MAN (CONT’D) Oh God, stop. Please stop. He climbs to his feet with what strength he can muster and frantically waves his arms around. The Truck continues its approach - It’s not slowing down. He realizes - and DASHES to the side - just as the vehicle speeds past. SCREECH! - The Truck comes to a complete stop just past the billboard. Brake-lights shine. The truck reverses back towards the bewildered man. The driver side window rolls down, revealing the mans savior - MURPHY sitting at the wheel with ROBERTA riding shotgun. -

(Anesthesia) Pulling Teeth Metallica

(Anesthesia) Pulling Teeth Metallica (How Sweet It Is) To Be Loved By You Marvin Gaye (Legend of the) Brown Mountain Light Country Gentlemen (Marie's the Name Of) His Latest Flame Elvis Presley (Now and Then There's) A Fool Such As I Elvis Presley (You Drive ME) Crazy Britney Spears (You're My) Sould and Inspiration Righteous Brothers (You've Got) The Magic Touch Platters 1, 2 Step Ciara and Missy Elliott 1, 2, 3 Gloria Estefan 10,000 Angels Mindy McCreedy 100 Years Five for Fighting 100% Pure Love Crystal Waters 100% Pure Love (Club Mix) Crystal Waters 1‐2‐3 Len Barry 1234 Coolio 157 Riverside Avenue REO Speedwagon 16 Candles Crests 18 and Life Skid Row 1812 Overture Tchaikovsky 19 Paul Hardcastle 1979 Smashing Pumpkins 1985 Bowling for Soup 1999 Prince 19th Nervous Breakdown Rolling Stones 1B Yo‐Yo Ma 2 Become 1 Spice Girls 2 Minutes to Midnight Iron Maiden 2001 Melissa Etheridge 2001 Space Odyssey Vangelis 2012 (It Ain't the End) Jay Sean 21 Guns Green Day 2112 Rush 21st Century Breakdown Green Day 21st Century Digital Boy Bad Religion 21st Century Kid Jamie Cullum 21st Century Schizoid Man April Wine 22 Acacia Avenue Iron Maiden 24‐7 Kevon Edmonds 25 or 6 to 4 Chicago 26 Miles (Santa Catalina) Four Preps 29 Palms Robert Plant 30 Days in the Hole Humble Pie 33 Smashing Pumpkins 33 (acoustic) Smashing Pumpkins 3am Matchbox 20 3am Eternal The KLF 3x5 John Mayer 4 in the Morning Gwen Stefani 4 Minutes to Save the World Madonna w/ Justin Timberlake 4 Seasons of Loneliness Boyz II Men 40 Hour Week Alabama 409 Beach Boys 5 Shots of Whiskey -

![The Manatee [Spring 2014]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7154/the-manatee-spring-2014-947154.webp)

The Manatee [Spring 2014]

Dorothy Cr aw fo rd M e ry lF aw Jo nH shuaW ealy Sus MANATEE THE alke an r Gr an Heather J t Ly e n nn n if At er w Mic oo helleFryar Ara d xieY er et A si nd a rea n Ambe L.Aste rLynn Alex Re Ne vi el ahvin s y D Gr ee n Ra e ch ld ael Hali Cassa ndraSha D w a ve ni r aA lH Bra usse ndeN. ini Hilar Mc yH Cle i e rtl herylA se e C .L ou x Ka tie T Smith im CarolynHask o in th yL idd ick LaurenA Ala sh nn ley aP Fe e rra ve ro ar K ristieMahoney SPRING 2014 SPRING The Manatee Seventh Annual Spring 2014 !! ! Copyright 2014 edited by Kristie Mahoney and Alanna Pevear Layout by Kristie Mahoney and Alanna Pevear Front Cover Design by Susan Grant All pieces in this journal were printed with permission from the author. Any works enclosed may be reprinted in another journal with permission from the editors. Published by Town & Country Reprographics 230 North Main St. Concord, NH 03301 603.226.2828 2 WHAT’S THE MANATEE? The Manatee is a literary journal run by the students of Southern New Hampshire University. We publish the best short fiction, poetry, essays, photos, and artwork of SNHU students, and we’re able to do it with generous funding from the awesome people in the School of Arts and Sciences. Visit http://it.snhu.edu/themanatee/ for information, submission guidelines and news. -

Roma Screenplay

IN ENGLISH ROMA Written and Directed by Alfonso Cuarón Dates in RED are meant only as a tool for the different departments for the specific historical accuracy of the scenes and are not intended to appear on screen. Thursday, September 3rd, 1970 INT. PATIO TEPEJI 21 - DAY Yellow triangles inside red squares. Water spreading over tiles. Grimy foam. The tile floor of a long and narrow patio stretching through the entire house: On one end, a black metal door gives onto the street. The door has frosted glass windows, two of which are broken, courtesy of some dejected goalee. CLEO, Cleotilde/Cleodegaria Gutiérrez, a Mixtec indigenous woman, about 26 years old, walks across the patio, nudging water over the wet floor with a squeegee. As she reaches the other end, the foam has amassed in a corner, timidly showing off its shiny little white bubbles, but - A GUSH OF WATER surprises and drags the stubborn little bubbles to the corner where they finally vanish, whirling into the sewer. Cleo picks up the brooms and buckets and carries them to - THE SMALL PATIO - Which is enclosed between the kitchen, the garage and the house. She opens the door to a small closet, puts away the brooms and buckets, walks into a small bathroom and closes the door. The patio remains silent except for a radio announcer, his enthusiasm melting in the distance, and the sad song of two caged little birds. The toilet flushes. Then: water from the sink. A beat, the door opens. Cleo dries her hands on her apron, enters the kitchen and disappears behind the door connecting it to the house. -

Alaskan Collection

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1995 Alaskan collection R. Glendon Brunk The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Brunk, R. Glendon, "Alaskan collection" (1995). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 1494. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/1494 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Maureen and Mike MANSFIELD LIBRARY The University ofMONTANA Permission is granted by the author to reproduce this material in its entirety, provided that this material is used for scholarly purposes and is properly cited in published works and reports. ** Please check "Yes" or "No" and provide signature ** Yes, I grant permission No, I do not grant permission Author's Signature Any copying for commercial purposes or financial gain may be undertaken only with the author's explicit consent. An Alaskan Collection by R. Glendon Brunk B.S. The University of Alaska, 1974 presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts The University of Montana 1995 Approved (by: Chairperson Dean, Graduate School Date UMI Number: EP35780 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. -

The Moody Blues Tour / Set List Project - Updated April 9, 2006

The Moody Blues Tour / Set List Project - updated April 9, 2006 compiled by Linda Bangert Please send any additions or corrections to Linda Bangert ([email protected]) and notice of any broken links to Neil Ottenstein ([email protected]). This listing of tour dates, set lists, opening acts, additional musicians was derived from many sources, as noted on each file. Of particular help were "Higher and Higher" magazine and their website at www.moodies- magazine.com and the Moody Blues Official Fan Club (OFC) Newsletters. For a complete listing of people who contributed, click here. Particular thanks go to Neil Ottenstein, who hosts these pages, and to Bob Hardy, who helped me get these pages converted to html. One-off live performances, either of the band as a whole or of individual members, are not included in this listing, but generally can be found in the Moody Blues FAQ in Section 8.7 - What guest appearances have the band members made on albums, television, concerts, music videos or print media? under the sub-headings of "Visual Appearances" or "Charity Appearances". The current version of the FAQ can be found at www.toadmail.com/~notten/FAQ-TOC.htm I've construed "additional musicians" to be those who played on stage in addition to the members of the Moody Blues. Although Patrick Moraz was legally determined to be a contract player, and not a member of the Moody Blues, I have omitted him from the listing of additional musicians for brevity. Moraz toured with the Moody Blues from 1978 through 1990. From 1965-1966 The Moody Blues were Denny Laine, Clint Warwick, Mike Pinder, Ray Thomas and Graeme Edge, although Warwick left the band sometime in 1966 and was briefly replaced with Rod Clarke. -

DAN KELLY's Ipod 80S PLAYLIST It's the End of The

DAN KELLY’S iPOD 80s PLAYLIST It’s The End of the 70s Cherry Bomb…The Runaways (9/76) Anarchy in the UK…Sex Pistols (12/76) X Offender…Blondie (1/77) See No Evil…Television (2/77) Police & Thieves…The Clash (3/77) Dancing the Night Away…Motors (4/77) Sound and Vision…David Bowie (4/77) Solsbury Hill…Peter Gabriel (4/77) Sheena is a Punk Rocker…Ramones (7/77) First Time…The Boys (7/77) Lust for Life…Iggy Pop (9/7D7) In the Flesh…Blondie (9/77) The Punk…Cherry Vanilla (10/77) Red Hot…Robert Gordon & Link Wray (10/77) 2-4-6-8 Motorway…Tom Robinson (11/77) Rockaway Beach…Ramones (12/77) Statue of Liberty…XTC (1/78) Psycho Killer…Talking Heads (2/78) Fan Mail…Blondie (2/78) This is Pop…XTC (3/78) Who’s Been Sleeping Here…Tuff Darts (4/78) Because the Night…Patty Smith Group (4/78) Ce Plane Pour Moi…Plastic Bertrand (4/78) Do You Wanna Dance?...Ramones (4/78) The Day the World Turned Day-Glo…X-Ray Specs (4/78) The Model…Kraftwerk (5/78) Keep Your Dreams…Suicide (5/78) Miss You…Rolling Stones (5/78) Hot Child in the City…Nick Gilder (6/78) Just What I Needed…The Cars (6/78) Pump It Up…Elvis Costello (6/78) Airport…Motors (7/78) Top of the Pops…The Rezillos (8/78) Another Girl, Another Planet…The Only Ones (8/78) All for the Love of Rock N Roll…Tuff Darts (9/78) Public Image…PIL (10/78) My Best Friend’s Girl…the Cars (10/78) Here Comes the Night…Nick Gilder (11/78) Europe Endless…Kraftwerk (11/78) Slow Motion…Ultravox (12/78) Roxanne…The Police (2/79) Lucky Number (slavic dance version)…Lene Lovich (3/79) Good Times Roll…The Cars (3/79) Dance -

Campfire Girls Go Motoring

The Camp Fire Girls Go Motoring OR Along the Road that Leads the Way By HILDEGARD G. FREY AUTHOR OF "The Camp Fire Girls in the Maine Woods," "The Camp Fire Girls at School," "The Camp Fire Girls at Onoway House." THE CAMP FIRE GIRLS GO MOTORING CHAPTER I. It is at Nyoda's bidding that I am writing the story of our automobile trip last September. She declared it was really too good to keep to ourselves, and as I was official reporter of the Winnebagos anyway, it was no more nor less than my solemn duty. Sahwah says that the only thing which was lacking about our adventures was that we didn't have a ride in a patrol wagon, but then Sahwah always did incline to the spectacular. And the whole train of events hinged on a commonplace circumstance which is in itself hardly worth recording; namely, that tan khaki was all the rage for outing suits last summer. But then, many an empire has fallen for a still slighter cause. The night after we came home from Onoway House and shortly before we started on that never-to-be-forgotten trip, I was sitting at the window watching the evening stars come out one after another. That line of Longfellow's came into my mind: "Silently, one by one, in the infinite meadows of heaven, Blossomed the lovely stars, the forget-me-nots of the angels." That quotation set me to thinking about Evangeline and the tragedy of her never finding her lover. Could it be possible, I thought, that two people could come so near to finding each other and yet be just too late? Not in these days of long distance telephones, I said to myself. -

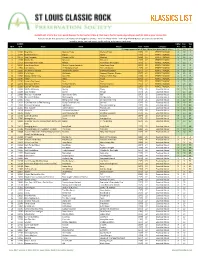

KLASSICS LIST Criteria

KLASSICS LIST criteria: 8 or more points (two per fan list, two for U-Man A-Z list, two to five for Top 95, depending on quartile); 1984 or prior release date Sources: ten fan lists (online and otherwise; see last page for details) + 2011-12 U-Man A-Z list + 2014 Top 95 KSHE Klassics (as voted on by listeners) sorted by points, Fan Lists count, Top 95 ranking, artist name, track name SLCRPS UMan Fan Top ID # ID # Track Artist Album Year Points Category A-Z Lists 95 35 songs appeared on all lists, these have green count info >> X 10 n 1 12404 Blue Mist Mama's Pride Mama's Pride 1975 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 1 2 12299 Dead And Gone Gypsy Gypsy 1970 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 2 3 11672 Two Hangmen Mason Proffit Wanted 1969 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 5 4 11578 Movin' On Missouri Missouri 1977 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 6 5 11717 Remember the Future Nektar Remember the Future 1973 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 7 6 10024 Lake Shore Drive Aliotta Haynes Jeremiah Lake Shore Drive 1971 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 9 7 11654 Last Illusion J.F. Murphy & Salt The Last Illusion 1973 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 12 8 13195 The Martian Boogie Brownsville Station Brownsville Station 1977 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 13 9 13202 Fly At Night Chilliwack Dreams, Dreams, Dreams 1977 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 14 10 11696 Mama Let Him Play Doucette Mama Let Him Play 1978 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 15 11 11547 Tower Angel Angel 1975 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 19 12 11730 From A Dry Camel Dust Dust 1971 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 20 13 12131 Rosewood Bitters Michael Stanley Michael Stanley 1972 27 PERFECT -

Roma (2018) Screenplay by Alfonso Cuarón

IN ENGLISH ROMA Written and Directed by Alfonso Cuarón Dates in RED are meant only as a tool for the different departments for the specific historical accuracy of the scenes and are not intended to appear on screen. Thursday, September 3rd, 1970 INT. PATIO TEPEJI 21 - DAY Yellow triangles inside red squares. Water spreading over tiles. Grimy foam. The tile floor of a long and narrow patio stretching through the entire house: On one end, a black metal door gives onto the street. The door has frosted glass windows, two of which are broken, courtesy of some dejected goalee. CLEO, Cleotilde/Cleodegaria Gutiérrez, a Mixtec indigenous woman, about 26 years old, walks across the patio, nudging water over the wet floor with a squeegee. As she reaches the other end, the foam has amassed in a corner, timidly showing off its shiny little white bubbles, but - A GUSH OF WATER surprises and drags the stubborn little bubbles to the corner where they finally vanish, whirling into the sewer. Cleo picks up the brooms and buckets and carries them to - THE SMALL PATIO - Which is enclosed between the kitchen, the garage and the house. She opens the door to a small closet, puts away the brooms and buckets, walks into a small bathroom and closes the door. The patio remains silent except for a radio announcer, his enthusiasm melting in the distance, and the sad song of two caged little birds. The toilet flushes. Then: water from the sink. A beat, the door opens. Cleo dries her hands on her apron, enters the kitchen and disappears behind the door connecting it to the house. -

The 1987 WNEW-FM Top 1027 Songs

The 1987 WNEW-FM Top 1027 Songs 1 Stairway To Heaven Led Zeppelin 2 Born To Run Bruce Springsteen 3 Layla Derek & The Dominos 4 Baba O'Riley The Who 5 (I Can't Get No) Satisfaction The Rolling Stones 6 Won't Get Fooled Again The Who 7 Hey Jude The Beatles 8 Freebird Lynyrd Skynyrd 9 Every Breath You Take The Police 10 Light My Fire The Doors 11 Whole Lotta Love Led Zeppelin 12 Kashmir Led Zeppelin 13 Thunder Road Bruce Springsteen 14 Nights In White Satin Moody Blues 15 Roxanne The Police 16 Jungleland Bruce Springsteen 17 Imagine John Lennon 18 A Day In The Life The Beatles 19 Suite: Judy Blue Eyes Crosby, Stills & Nash 20 Lola The Kinks 21 Dazed & Confused Led Zeppelin 22 Like A Rolling Stone Bob Dylan 23 Roundabout Yes 24 Jump Van Halen 25 Under My Thumb The Rolling Stones 26 Smoke On The Water Deep Purple 27 Rosalita Bruce Springsteen 28 L. A. Woman The Doors 29 Immigrant Song Led Zeppelin 30 Another Brick In The Wall, Pt. 2 Pink Floyd 31 Over The Hills & Far Away Led Zeppelin 32 Sympathy For The Devil The Rolling Stones 33 Johnny B. Goode Chuck Berry 34 My Generation The Who 35 Money Pink Floyd 36 Good Times Bad Times Led Zeppelin 37 Funeral For A Friend Elton John 38 Love Reign O'er Me The Who 39 Who Are You The Who 40 Brown Sugar The Rolling Stones 41 American Pie Don Mclean 42 Sunshine Of Your Love Cream 43 Purple Haze Jimi Hendrix 44 Hotel California The Eagles 45 Tempted Squeeze 46 I Wanna Hold Your Hand The Beatles 47 You Can't Always Get What You Want The Rolling Stones 48 I Saw Her Standing There The Beatles 49 Communication -

Poemes De Terre)

1 2 YUKON GOLD (Poemes de Terre) Collected Poems 1971-2009 Mike Finley 3 Copyright © 2009 by Kraken Press 4 Table of Contents Cosmetic Dentistry.............................................................16 Truck Stop...........................................................................18 Haircut................................................................................19 The Eyed Eclair .................................................................20 In the Hot Springs Parking Lot...........................................21 The Movie Under the Blindfold.........................................22 Truth Never Frightens ........................................................23 Nighttime At The Christian Retreat....................................25 Fever...................................................................................27 The Art of Negotiation........................................................28 Bells Are Ringing...............................................................29 Ghost ..................................................................................30 Pathetic Fallacy...................................................................31 Empty Jug...........................................................................32 Your Human Being.............................................................33 A Compact..........................................................................34 The Important Thing...........................................................35 The Heart Sings a Song