Alaskan Collection

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fro F M V M°J° Nixon Is Mojo Is in A

TW O G R EA T W H A T'S FILMS FROMI HAPPENING S O U TH T O VIC AFR ICA DUNLO P 9A 11A The Arts and Entertainment Section of the Daily Nexus OF NOTE THIS WEEK 1 1 « Saturday: Don Henley at the Santa Barbara County Bowl. 7 p.m. Sunday: The Jefferson Airplane re turns. S.B. County Bowl, 3 p.m. Tuesday: kd. long and the reclines, country music from Canada. 8 p.m. at the Ventura Theatre Wednesday: Eek-A-M ouse deliv ers fun reggae to the Pub. 8 p.m. Definately worth blowing off Countdown for. Tonight: "Gone With The Wind," The Classic is back at Campbell Hall, 7 p.m. Tickets: $3 w/student ID 961-2080 Tomorrow: The Second Animation -in n i Celebration, at the Victoria St. mmm Theatre until Oct. 8. Saturday: The Flight of the Eagle at Campbell Hall, 8 p.m. H i « » «MI HBfi MIRiM • ». frOf M v M°j° Nixon is Mojo is in a College of Creative Studies' Art vJVl 1T1.J the man your band with his Gallery: Thomas Nozkowski' paint ings. Ends Oct. 28. University Art Museum: The Tt l t f \ T/'\parents prayed partner, Skid Other Side of the Moon: the W orldof Adolf Wolfli until Nov. 5; Free. J y l U J \ J y ou'd never Roper, who Phone: 961-2951 Women's Center Gallery: Recent Works by Stephania Serena. Large grow up to be. plays the wash- color photgraphs that you must see to believe; Free. -

Z-Nation - EP 2XX - FULL PINK (10/10/15) 2

EPISODE 200 "PEACE OF MURPHY" Written by REDACTED Directed by REDACTED PRODUCTION DRAFT 08/01/15 FULL BLUE 08/05/15 The Asylum Los Angeles 45315 FADE IN: 1 EXT. COUNTRY ROAD - DAY 1 We open on a desolate stretch of back-road. The mid-day sun beats down. There’s no noise. No crickets chirping. Like most places in this world: dead and way too quiet. A RUSTED BILLBOARD casts a shadow across the sweltering tarmac. A cartoon bear warning visitors that “ONLY YOU CAN PREVENT FOREST FIRES”. Behind the billboard, in the distance - AN ATOMIC FIRE RAVAGES THE LANDSCAPE. SLOW FOOTSTEPS break the silence. A WOUNDED-MAN drags himself down the road. Blackened and burned: The clothes are literally falling from his back. He’s sick and desperate - A victim of radiation poisoning. The Wounded-Man reaches the shadow of the billboard before stumbling - And collapsing to his knees. He looks towards the sky. Coughs. WOUNDED-MAN Please. Somebody... Anybody? ANGLE ON: A VEHICLE APPROACHING FROM THE DISTANCE The man smiles, his prayers have been answered. WOUNDED-MAN (CONT’D) Oh God, stop. Please stop. He climbs to his feet with what strength he can muster and frantically waves his arms around. The Truck continues its approach - It’s not slowing down. He realizes - and DASHES to the side - just as the vehicle speeds past. SCREECH! - The Truck comes to a complete stop just past the billboard. Brake-lights shine. The truck reverses back towards the bewildered man. The driver side window rolls down, revealing the mans savior - MURPHY sitting at the wheel with ROBERTA riding shotgun. -

(Anesthesia) Pulling Teeth Metallica

(Anesthesia) Pulling Teeth Metallica (How Sweet It Is) To Be Loved By You Marvin Gaye (Legend of the) Brown Mountain Light Country Gentlemen (Marie's the Name Of) His Latest Flame Elvis Presley (Now and Then There's) A Fool Such As I Elvis Presley (You Drive ME) Crazy Britney Spears (You're My) Sould and Inspiration Righteous Brothers (You've Got) The Magic Touch Platters 1, 2 Step Ciara and Missy Elliott 1, 2, 3 Gloria Estefan 10,000 Angels Mindy McCreedy 100 Years Five for Fighting 100% Pure Love Crystal Waters 100% Pure Love (Club Mix) Crystal Waters 1‐2‐3 Len Barry 1234 Coolio 157 Riverside Avenue REO Speedwagon 16 Candles Crests 18 and Life Skid Row 1812 Overture Tchaikovsky 19 Paul Hardcastle 1979 Smashing Pumpkins 1985 Bowling for Soup 1999 Prince 19th Nervous Breakdown Rolling Stones 1B Yo‐Yo Ma 2 Become 1 Spice Girls 2 Minutes to Midnight Iron Maiden 2001 Melissa Etheridge 2001 Space Odyssey Vangelis 2012 (It Ain't the End) Jay Sean 21 Guns Green Day 2112 Rush 21st Century Breakdown Green Day 21st Century Digital Boy Bad Religion 21st Century Kid Jamie Cullum 21st Century Schizoid Man April Wine 22 Acacia Avenue Iron Maiden 24‐7 Kevon Edmonds 25 or 6 to 4 Chicago 26 Miles (Santa Catalina) Four Preps 29 Palms Robert Plant 30 Days in the Hole Humble Pie 33 Smashing Pumpkins 33 (acoustic) Smashing Pumpkins 3am Matchbox 20 3am Eternal The KLF 3x5 John Mayer 4 in the Morning Gwen Stefani 4 Minutes to Save the World Madonna w/ Justin Timberlake 4 Seasons of Loneliness Boyz II Men 40 Hour Week Alabama 409 Beach Boys 5 Shots of Whiskey -

"Eustace the Monk" and Compositional Techniques

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2013 An original composition, Symphony No. 1, "Eustace the Monk" and compositional techniques used to elicit musical humor Samuel Howard Stokes Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Stokes, Samuel Howard, "An original composition, Symphony No. 1, "Eustace the Monk" and compositional techniques used to elicit musical humor" (2013). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 1053. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/1053 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. AN ORIGINAL COMPOSITION, SYMPHONY NO. 1, "EUSTACE THE MONK" AND COMPOSITIONAL TECHNIQUES USED TO ELICIT MUSICAL HUMOR A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College In partial fulfillment of the Requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The School of Music by Samuel Stokes B.M., University of Central Missouri, 2002 M.A., University of Central Missouri, 2005 M.M., The Florida State University, 2006 May 2013 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank Dinos Constantinides for his valuable guidance and enthusiasm in my development as a composer. He has expanded my horizons by making me think outside of the box while leaving me enough room to find my own compositional voice. -

"WEIRD AL" YANKOVIC: POLKAS, PARODIES and the POWER of SATIRE by Chuck Miller Originally Published in Goldmine #514

"WEIRD AL" YANKOVIC: POLKAS, PARODIES AND THE POWER OF SATIRE By Chuck Miller Originally published in Goldmine #514 Al Yankovic strapped on his accordion, ready to perform. All he had to do was impress some talent directors, and he would be on The Gong Show, on stage with Chuck Barris and the Unknown Comic and Jaye P. Morgan and Gene Gene the Dancing Machine. "I was in college," said Yankovic, "and a friend and I drove down to LA for the day, and auditioned for The Gong Show. And we did a song called 'Mr. Frump in the Iron Lung.' And the audience seemed to enjoy it, but we never got called back. So we didn't make the cut for The Gong Show." But while the Unknown Co mic and Gene Gene the Dancing Machine are currently brain stumpers in 1970's trivia contests, the accordionist who failed the Gong Show taping became the biggest selling parodist and comedic recording artist of the past 30 years. His earliest parodies were recorded with an accordion in a men's room, but today, he and his band have replicated tracks so well one would think they borrowed the original master tape, wiped off the original vocalist, and superimposed Yankovic into the mix. And with MTV, MuchMusic, Dr. Demento and Radio Disney playing his songs right out of the box, Yankovic has reached a pinnacle of success and longevity most artists can only imagine. Alfred Yankovic was born in Lynwood, California on October 23, 1959. Seven years later, his parents bought him an accordion for his birthday. -

![The Manatee [Spring 2014]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7154/the-manatee-spring-2014-947154.webp)

The Manatee [Spring 2014]

Dorothy Cr aw fo rd M e ry lF aw Jo nH shuaW ealy Sus MANATEE THE alke an r Gr an Heather J t Ly e n nn n if At er w Mic oo helleFryar Ara d xieY er et A si nd a rea n Ambe L.Aste rLynn Alex Re Ne vi el ahvin s y D Gr ee n Ra e ch ld ael Hali Cassa ndraSha D w a ve ni r aA lH Bra usse ndeN. ini Hilar Mc yH Cle i e rtl herylA se e C .L ou x Ka tie T Smith im CarolynHask o in th yL idd ick LaurenA Ala sh nn ley aP Fe e rra ve ro ar K ristieMahoney SPRING 2014 SPRING The Manatee Seventh Annual Spring 2014 !! ! Copyright 2014 edited by Kristie Mahoney and Alanna Pevear Layout by Kristie Mahoney and Alanna Pevear Front Cover Design by Susan Grant All pieces in this journal were printed with permission from the author. Any works enclosed may be reprinted in another journal with permission from the editors. Published by Town & Country Reprographics 230 North Main St. Concord, NH 03301 603.226.2828 2 WHAT’S THE MANATEE? The Manatee is a literary journal run by the students of Southern New Hampshire University. We publish the best short fiction, poetry, essays, photos, and artwork of SNHU students, and we’re able to do it with generous funding from the awesome people in the School of Arts and Sciences. Visit http://it.snhu.edu/themanatee/ for information, submission guidelines and news. -

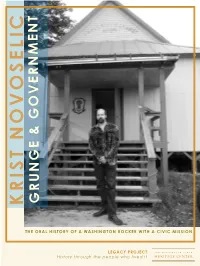

Krist Novoselic

OVERNMENT G & E GRUNG KRIST NOVOSELIC THE ORAL HISTORY OF A WASHINGTON ROCKER WITH A CIVIC MISSION LEGACY PROJECT History through the people who lived it Krist Novoselic Research by John Hughes and Lori Larson Transcripti on by Lori Larson Interviews by John Hughes October 14, 2008 John Hughes: This is October 14, 2008. I’m John Hughes, Chief Oral Historian for the Washington State Legacy Project, with the Offi ce of the Secretary of State. We’re in Deep River, Wash., at the home of Krist Novoselic, a 1984 graduate of Aberdeen High School; a founding member of the band Nirvana with his good friend Kurt Cobain; politi cal acti vist, chairman of the Wahkiakum County Democrati c Party, author, fi lmmaker, photographer, blogger, part-ti me radio host, While doing reseach at the State Archives in 2005, Novoselic volunteer disc jockey, worthy master of the Grays points to Grays River in Wahkiakum County, where he lives. Courtesy Washington State Archives River Grange, gentleman farmer, private pilot, former commercial painter, ex-fast food worker, proud son of Croati a, and an amateur Volkswagen mechanic. Does that prett y well cover it, Krist? Novoselic: And chairman of FairVote to change our democracy. Hughes: You know if you ever decide to run for politi cal offi ce, your life is prett y much an open book. And half of it’s on YouTube, like when you tried for the Guinness Book of World Records bass toss on stage with Nirvana and it hits you on the head, and then Kurt (Cobain) kicked you in the butt . -

Roma Screenplay

IN ENGLISH ROMA Written and Directed by Alfonso Cuarón Dates in RED are meant only as a tool for the different departments for the specific historical accuracy of the scenes and are not intended to appear on screen. Thursday, September 3rd, 1970 INT. PATIO TEPEJI 21 - DAY Yellow triangles inside red squares. Water spreading over tiles. Grimy foam. The tile floor of a long and narrow patio stretching through the entire house: On one end, a black metal door gives onto the street. The door has frosted glass windows, two of which are broken, courtesy of some dejected goalee. CLEO, Cleotilde/Cleodegaria Gutiérrez, a Mixtec indigenous woman, about 26 years old, walks across the patio, nudging water over the wet floor with a squeegee. As she reaches the other end, the foam has amassed in a corner, timidly showing off its shiny little white bubbles, but - A GUSH OF WATER surprises and drags the stubborn little bubbles to the corner where they finally vanish, whirling into the sewer. Cleo picks up the brooms and buckets and carries them to - THE SMALL PATIO - Which is enclosed between the kitchen, the garage and the house. She opens the door to a small closet, puts away the brooms and buckets, walks into a small bathroom and closes the door. The patio remains silent except for a radio announcer, his enthusiasm melting in the distance, and the sad song of two caged little birds. The toilet flushes. Then: water from the sink. A beat, the door opens. Cleo dries her hands on her apron, enters the kitchen and disappears behind the door connecting it to the house. -

Ent-2002-03-01.Pdf

ENTERTAINMENTpage 15 Technique • Friday, March 1, 2002 • 15 Looking for break action? It’s on his business card The Live List is your place to check out “Voice of the Yellow Jackets” is one of ENTERTAINMENT the many options for live entertain- Director of Broadcasting Wes ment if you’re staying in the ATL this Durham’s titles. Read up on this Technique • Friday, March 1, 2002 spring break. Page 16 member of the Tech family. Page 24 Morisette’s ‘Under Rug Swept’ not to be discarded Alanis Morissette has found her inner angst again with her newest single, “Hands Clean,” from her newest CD, with which she proves her growth from early releases like Jagged Little Pill which brought her fast fame. By Rob Hill and Danielle Bradley off the deep end. Staff Writers Some of the middle tracks are where listeners may become bored, Artist: Alanis Morissette distracted, or even sick of the mo- Album: Under Rug Swept notony of a “not so newly rich” girl Label: Maverick complaining about the same things Rating: yyy 1/2 we heard about three years ago. Per- sonally we got our fill back then. The angst is back. With Alanis Even the instrumentals of the fourth Morissette’s newest record, Under track, “Flinch,” remind the casual Rug Swept, we have a record closer listener of every Matchbox Twenty in spirit to her smash debut, Jagged song ever written. Fame and for- Little Pill. Well, at least that’s what tune certainly need not detract from she’s trying for. Perhaps trying a bit the value and agenda of an artist, too hard in the process. -

The 48 Hour Film Project the Sweet One All Shows Start Approximately 10Pm, 21+, No Cover Go to Our Facebook for Band and Burlesque Listings for This Month

SEPTEMBER 2017 TYBEEBEACHCOMBER.COM Island’s Guide for fun ! The Tybee Island Marine Science Center CONFESSIONS of A Reformed Beer Snob HURRICANE SEASON IT’S BAAACK! The 48 Hour Film Project The Sweet One All shows start approximately 10pm, 21+, no cover Go to our Facebook for Band and Burlesque Listings for this Month 13 Tybrisa St. | Tybee Island 912 -786 -5100 Tybee Post Theater ................................................... 472-4790 Tybee Fishing License (Chu’s on Campbell) .......................... 786-5904 Area Code Dizzy Dean’s Liquor, Beer & Wine .............................. 786-4500 912Digits XYZ Liquors .............................................................. 786-4822 Tybee Golf Carts ....................................................... 226-9676 Emergency- Police, Fire, Medical ............................... 911 Fat Tire Bikes ........................................................... 786-4013 Police NON-Emergency ............................................. 786-5600 Tim’s Bike & Beach Gear ........................................... 786-8467 Fire NON-Emergency ................................................ 472-5062 Burke’s Beach Rentals, Inc ........................................ 547-8145 Ocean Rescue .......................................................... 786-9873 Boogie Scooters Rentals ........................................... 472-4266 City Hall ................................................................... 786-4573 Shuttle Services Library .................................................................... -

The Moody Blues Tour / Set List Project - Updated April 9, 2006

The Moody Blues Tour / Set List Project - updated April 9, 2006 compiled by Linda Bangert Please send any additions or corrections to Linda Bangert ([email protected]) and notice of any broken links to Neil Ottenstein ([email protected]). This listing of tour dates, set lists, opening acts, additional musicians was derived from many sources, as noted on each file. Of particular help were "Higher and Higher" magazine and their website at www.moodies- magazine.com and the Moody Blues Official Fan Club (OFC) Newsletters. For a complete listing of people who contributed, click here. Particular thanks go to Neil Ottenstein, who hosts these pages, and to Bob Hardy, who helped me get these pages converted to html. One-off live performances, either of the band as a whole or of individual members, are not included in this listing, but generally can be found in the Moody Blues FAQ in Section 8.7 - What guest appearances have the band members made on albums, television, concerts, music videos or print media? under the sub-headings of "Visual Appearances" or "Charity Appearances". The current version of the FAQ can be found at www.toadmail.com/~notten/FAQ-TOC.htm I've construed "additional musicians" to be those who played on stage in addition to the members of the Moody Blues. Although Patrick Moraz was legally determined to be a contract player, and not a member of the Moody Blues, I have omitted him from the listing of additional musicians for brevity. Moraz toured with the Moody Blues from 1978 through 1990. From 1965-1966 The Moody Blues were Denny Laine, Clint Warwick, Mike Pinder, Ray Thomas and Graeme Edge, although Warwick left the band sometime in 1966 and was briefly replaced with Rod Clarke. -

The Potential of Informative Comedy Music As Supplementary Teaching Material

http://dx.doi.org/10.7592/EJHR2018.6.3.mckeague European Journal of Humour Research 6 (3) 30–49 www.europeanjournalofhumour.org Lyrical lessons: The potential of informative comedy music as supplementary teaching material Dr. Matthew McKeague Kutztown University of Pennsylvania [email protected] Abstract The comedic arts have provided opportunities for humourists to spread information to audiences, sometimes intentionally and other times as a side effect while trying to create laughter. Educators have also found success incorporating comedy into the classroom with humorous activities. While research regarding comedy as a tool to spread information or educate audiences has focused primarily on literature, broadcast media, and film, the area of informative comedy implemented through music remains relatively unexplored. In this paper, the researcher defines ‘informative comedy’ and takes a critical literacy approach analysing song samples of comedy musician “Weird Al” Yankovic—one of the notable comedic music artists in the 20th and 21st centuries—and discusses how his music could be used in a classroom setting. While comedy such as Yankovic’s is not designed to be an educational tool, the researcher suggests that his songs could be used as supplementary materials in the classroom to reinforce concepts specifically regarding cultural issues through commentary as well as lessons in science and grammar. A central aspect of this exploratory paper involves Yankovic’s mix of comedy and informative content focused on culture in the United States, using the popular music genre to convey ideas in ways that may be more palatable for wider audiences and that could be used to assist classroom instruction.