A Portrait of the Visual Arts Meeting the Challenges of a New Era

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Visual Arts – Specific Rules/Guidelines

Visual Arts – Specific Rules/Guidelines VISUAL ARTS include many art forms that are visual in nature. The artist (student submitting entry) is a person who captures their own thoughts and ideas to create a visual piece of art. Accepted forms of visual art include: Collages, photographic collages (multiple photos cut/pasted), computer-generated image, design, drawing, painting, and printmaking. Non-accepted forms of visual art include: 3D artwork (artwork that is not flat on the surface). Reproductions or enlargements of another artwork. Reflect on the 2020-2021 Theme: I Matter Because… An explanation of the art form might be a useful addition to the artist statement. Whether an entry displays use of formal technique or a simple approach, it will be judged primarily on how well the student uses his or her artistic vision to portray the theme, originality and creativity. Copyright: Use of copyrighted material, including any copyrighted cartoon characters or likeness thereof, is not acceptable in any visual arts submission, with the following exceptions: • Visual artwork may include public places, well-known products, trademarks or certain other copyrighted material as long as that copyrighted material is incidental to the subject matter of the piece and/or is a smaller element of a whole. The resulting work cannot try to establish an association between the student and the trademark/business/material, or influence the purchase/non-purchase of the trademarked good. • Visual arts collages may include portions of existing copyrighted works, such as photographs, magazine clippings, internet images and type cut out of a newspaper, as long as those portions of copyrighted works are used to create a completely new and different work of art. -

All These Post-1965 Movements Under the “Conceptual Art” Umbrella

All these post-1965 movements under the “conceptual art” umbrella- Postminimalism or process art, Site Specific works, Conceptual art movement proper, Performance art, Body Art and all combinations thereof- move the practice of art away from art-as-autonomous object, and art-as-commodification, and towards art-as-experience, where subject becomes object, hierarchy between subject and object is critiqued and intersubjectivity of artist, viewer and artwork abounds! Bruce Nauman, Live-Taped Video Corridor, 1970, Conceptual Body art, Postmodern beginning “As opposed to being viewers of the work, once again they are viewers in it.” (“Subject as Object,” p. 199) http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9IrqXiqgQBo A Postmodern beginning: Body art and Performance art as critique of art-as-object recap: -Bruce Nauman -Vito Acconci focus on: -Chris Burden -Richard Serra -Carolee Schneemann - Hannah Wilke Chapter 3, pp. 114-132 (Carolee Schneemann and Hannah Wilke, First Generation Feminism) Bruce Nauman, Bouncing Two Balls Between the Floor and Ceiling with Changing Rhythms, 1967-1968. 16mm film transferred to video (black and white, sound), 10 min. Body art/Performance art, Postmodern beginning- performed elementary gestures in the privacy of his studio and documented them in a variety of media Vito Acconci, Following Piece, 1969, Body art, Performance art- outside the studio, Postmodern beginning Video documentation of the event Print made from bite mark Vito Acconci, Trademarks, 1970, Body art, Performance art, Postmodern beginning Video and Print documentation -

Dolan Middle School Visual Art Course Syllabus 6

DOLAN MIDDLE SCHOOL VISUAL ART COURSE SYLLABUS 6TH through 8th Grade Teacher: Mrs. Marchetti Course title: Visual Arts Course Description: 6th and 7th Grade: Students will spend the semester completing art projects designed to develop the student’s individual ideas and talents as an artist. The students will explore concepts that will increase their knowledge about art materials and use, art equipment, art history, and the application of it. 8th Grade: Students will further explore the many venues of art education. Students will focus on higher order thinking skills while concentrating on specific applications of the given media. Students will use their skills in various relevant and rigorous projects. Scope and Sequence: The Visual Art Curriculum is divided into the 6 major aspects of art creation. These will serve as a solid foundation for High School and beyond. Projects that cover each of the following aspects will be divided equally over the course of the semester. 1. Drawing: Foundation skill that is taught in many different ways throughout the semester. These may include pencil, charcoal, pastels, pen & ink, and colored pencil. 2. Painting: This are will explore two primary media techniques, watercolor and acrylic. 3. Sculpture: This area exposes students to the unique characteristics of creating in 3 dimensions and usually includes wire and plastering. 4. Printmaking: This area examines the creation process through the lens of producing repeated images. This is usually done through block and plate printing. 5. New Media: This area looks at Contemporary Design, illustration, and photography within the context of computer-based and digital media. -

Grade by Grade Fine Arts Content Standards

Montgomery County Public Schools Pre-k–12 Visual Art Curriculum Framework Standard I: Students will demonstrate the ability to perceive, interpret, and respond to ideas, experiences, and the environment through visual art. Indicator 1: Identify and describe observed form By the end of the following grades, students will know and be able to do everything in the previous grade and the following content: Pre-K Kindergarten Grade 1 Grade 2 I.1.PK.a. I.1.K.a. I.1.1.a. I.1.2.a. Identify colors, lines, shapes, and Describe colors, lines, shapes, and Describe colors, lines, shapes, textures, Describe colors, lines, shapes, textures, textures that are found in the textures found in the environment. and forms found in observed objects forms, and space found in observed environment. and the environment. objects and the environment. I.1.K.b. I.1.1.b. I.1.2.b. I.1.PK.b. Represent observed form by combining Represent observed physical qualities Represent observed physical qualities Use colors, lines, shapes, and textures colors, lines, shapes, and textures. of people, animals, and objects in the of people, animals, and objects in the to communicate observed form. environment using color, line, shape, environment using color, line, shape, texture, and form. texture, form, and space. Clarifying Example: Clarifying Example: Clarifying Example: Clarifying Example: Given examples of lines, the student Take a walk around the school property. The student describes colors, lines, Given examples of assemblage, the identifies lines found in the trunk and Find and describe colors, lines, shapes, shapes, textures, and forms observed in a student describes colors, lines, shapes, branches of a tree. -

Impressionist and Modern Art Introduction Art Learning Resource – Impressionist and Modern Art

art learning resource – impressionist and modern art Introduction art learning resource – impressionist and modern art This resource will support visits to the Impressionist and Modern Art galleries at National Museum Cardiff and has been written to help teachers and other group leaders plan a successful visit. These galleries mostly show works of art from 1840s France to 1940s Britain. Each gallery has a theme and displays a range of paintings, drawings, sculpture and applied art. Booking a visit Learning Office – for bookings and general enquires Tel: 029 2057 3240 Email: [email protected] All groups, whether visiting independently or on a museum-led visit, must book in advance. Gallery talks for all key stages are available on selected dates each term. They last about 40 minutes for a maximum of 30 pupils. A museum-led session could be followed by a teacher-led session where pupils draw and make notes in their sketchbooks. Please bring your own materials. The information in this pack enables you to run your own teacher-led session and has information about key works of art and questions which will encourage your pupils to respond to those works. Art Collections Online Many of the works here and others from the Museum’s collection feature on the Museum’s web site within a section called Art Collections Online. This can be found under ‘explore our collections’ at www.museumwales.ac.uk/en/art/ online/ and includes information and details about the location of the work. You could use this to look at enlarged images of paintings on your interactive whiteboard. -

Cubism in America

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Sheldon Museum of Art Catalogues and Publications Sheldon Museum of Art 1985 Cubism in America Donald Bartlett Doe Sheldon Memorial Art Gallery Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sheldonpubs Part of the Art and Design Commons Doe, Donald Bartlett, "Cubism in America" (1985). Sheldon Museum of Art Catalogues and Publications. 19. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sheldonpubs/19 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Sheldon Museum of Art at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sheldon Museum of Art Catalogues and Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. RESOURCE SERIES CUBISM IN SHELDON MEMORIAL ART GALLERY AMERICA Resource/Reservoir is part of Sheldon's on-going Resource Exhibition Series. Resource/Reservoir explores various aspects of the Gallery's permanent collection. The Resource Series is supported in part by grants from the National Endowment for the Arts. A portion of the Gallery's general operating funds for this fiscal year has been provided through a grant from the Institute of Museum Services, a federal agency that offers general operating support to the nation's museums. Henry Fitch Taylor Cubis t Still Life, c. 19 14, oil on canvas Cubism in America .".. As a style, Cubism constitutes the single effort which began in 1907. Their develop most important revolution in the history of ment of what came to be called Cubism art since the second and third decades of by a hostile critic who took the word from a the 15th century and the beginnings of the skeptical Matisse-can, in very reduced Renaissance. -

Visual Arts Curriculum Guide

Visual Arts Madison Public Schools Madison, Connecticut Dear Interested Reader: The following document is the Madison Public Schools’ Visual Arts Curriculum Guide If you plan to use the whole or any parts of this document, it would be appreciated if you credit the Madison Public Schools, Madison, Connecticut for the work. Thank you in advance. Table of Contents Foreword Program Overview Program Components and Framework · Program Components and Framework · Program Philosophy · Grouping Statement · Classroom Environment Statement · Arts Goals Learner Outcomes (K - 12) Scope and Sequence · Student Outcomes and Assessments - Grades K - 4 · Student Outcomes and Assessments - Grades 5 - 8 · Student Outcomes and Assessments / Course Descriptions - Grades 9 - 12 · Program Support / Celebration Statement Program Implementation: Guidelines and Strategies · Time Allotments · Implementation Assessment Guidelines and Procedures · Evaluation Resources Materials · Resources / Materials · National Standards · State Standards Foreword The art curriculum has been developed for the Madison school system and is based on the newly published national Standards for Arts Education, which are defined as Dance, Music, Theater, and Visual Arts. The national standards for the Visual Arts were developed by the National Art Education Association Art Standard Committee to reflect a national consensus of the views of organizations and individuals representing educators, parents, artists, professional associations in education and in the arts, public and private educational institutions, philanthropic organizations, and leaders from government, labor, and business. The Visual Arts Curriculum for the Madison School System will provide assistance and support to Madison visual arts teachers and administrators in the implementation of a comprehensive K - 12 visual arts program. The material described in this guide will assist visual arts teachers in designing visual arts lesson plans that will give each student the chance to meet the content and performance, or achievement, standards in visual arts. -

Off Museum! Performance Art That Turned the Street Into 'Theatre,' Circa 1964 Tokyo

Performance Paradigm 2 (March 2006) Off Museum! Performance Art That Turned the Street into ‘Theatre,’ Circa 1964 Tokyo Midori Yoshimoto Performance art was an integral part of the urban fabric of Tokyo in the late 1960s. The so- called angura, the Japanese abbreviation for ‘underground’ culture or subculture, which mainly referred to film and theatre, was in full bloom. Most notably, Tenjô Sajiki Theatre, founded by the playwright and film director Terayama Shûji in 1967, and Red Tent, founded by Kara Jûrô also in 1967, ruled the underground world by presenting anti-authoritarian plays full of political commentaries and sexual perversions. The butoh dance, pioneered by Hijikata Tatsumi in the late 1950s, sometimes spilled out onto streets from dance halls. Students’ riots were ubiquitous as well, often inciting more physically violent responses from the state. Street performances, however, were introduced earlier in the 1960s by artists and groups, who are often categorised under Anti-Art, such as the collectives Neo Dada (originally known as Neo Dadaism Organizer; active 1960) and Zero Jigen (Zero Dimension; active 1962-1972). In the beginning of Anti-Art, performances were often by-products of artists’ non-conventional art-making processes in their rebellion against the artistic institutions. Gradually, performance art became an autonomous artistic expression. This emergence of performance art as the primary means of expression for vanguard artists occurred around 1964. A benchmark in this aesthetic turning point was a group exhibition and outdoor performances entitled Off Museum. The recently unearthed film, Aru wakamono-tachi (Some Young People), created by Nagano Chiaki for the Nippon Television Broadcasting in 1964, documents the performance portion of Off Museum, which had been long forgotten in Japanese art history. -

Is Marina Abramović the World's Best-Known Living Artist? She Might

Abrams, Amah-Rose. “Marina Abramovic: A Woman’s World.” Sotheby’s. May 10, 2021 Is Marina Abramović the world’s best-known living artist? She might well be. Starting out in the radical performance art scene in the early 1970s, Abramović went on to take the medium to the masses. Working with her collaborator and partner Ulay through the 1980s and beyond, she developed long durational performance art with a focus on the body, human connection and endurance. In The Lovers, 1998, she and Ulay met in the middle of the Great Wall of China and ended their relationship. For Balkan Baroque, 1997, she scrubbed clean a huge number of cow bones, winning the Golden Lion at the Venice Biennale for her work. And in The Artist is Present 2010, performed at MoMA in New York, she sat for eight hours a day engaging in prolonged eye contact over three months – it was one of the most popular exhibits in the museum’s history. Since then, she has continued to raise the profile of artists around the world by founding the Marina Abramović Institute, her organisation aimed at expanding the accessibility of time- based work and creating new possibilities for collaboration among thinkers of all fields. MARINA ABRAMOVIĆ / ULAY, THE LOVERS, MARCH–JUNE 1988, A PERFORMANCE THAT TOOK PLACE ACROSS 90 DAYS ON THE GREAT WALL OF CHINA. © MARINA ABRAMOVIĆ AND ULAY, COURTESY: THE MARINA ABRAMOVIĆ ARCHIVES / DACS 2021. Fittingly for someone whose work has long engaged with issues around time, Marina Abramović has got her lockdown routine down. She works out, has a leisurely breakfast, works during the day and in the evening, she watches films. -

GREEN PAPER Page 1

AMERICANS FOR THE ARTS PUBLIC ART NETWORK COUNCIL: GREEN PAPER page 1 Why Public Art Matters Cities gain value through public art – cultural, social, and economic value. Public art is a distinguishing part of our public history and our evolving culture. It reflects and reveals our society, adds meaning to our cities and uniqueness to our communities. Public art humanizes the built environment and invigorates public spaces. It provides an intersection between past, present and future, between disciplines, and between ideas. Public art is freely accessible. Cultural Value and Community Identity American cities and towns aspire to be places where people want to live and want to visit. Having a particular community identity, especially in terms of what our towns look like, is becoming even more important in a world where everyplace tends to looks like everyplace else. Places with strong public art expressions break the trend of blandness and sameness, and give communities a stronger sense of place and identity. When we think about memorable places, we think about their icons – consider the St. Louis Arch, the totem poles of Vancouver, the heads at Easter Island. All of these were the work of creative people who captured the spirit and atmosphere of their cultural milieu. Absent public art, we would be absent our human identities. The Artist as Contributor to Cultural Value Public art brings artists and their creative vision into the civic decision making process. In addition the aesthetic benefits of having works of art in public places, artists can make valuable contributions when they are included in the mix of planners, engineers, designers, elected officials, and community stakeholders who are involved in planning public spaces and amenities. -

Robert Morris, Minimalism, and the 1960S

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 1988 The Politics of Experience: Robert Morris, Minimalism, and the 1960s Maurice Berger Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/1646 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. -

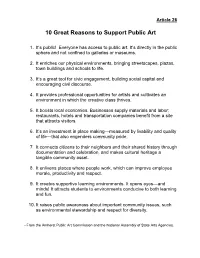

10 Great Reasons to Support Public Art

Article 26 10 Great Reasons to Support Public Art 1. It’s public! Everyone has access to public art. It’s directly in the public sphere and not confined to galleries or museums. 2. It enriches our physical environments, bringing streetscapes, plazas, town buildings and schools to life. 3. It’s a great tool for civic engagement, building social capital and encouraging civil discourse. 4. It provides professional opportunities for artists and cultivates an environment in which the creative class thrives. 5. It boosts local economies. Businesses supply materials and labor; restaurants, hotels and transportation companies benefit from a site that attracts visitors. 6. It’s an investment in place making—measured by livability and quality of life—that also engenders community pride. 7. It connects citizens to their neighbors and their shared history through documentation and celebration, and makes cultural heritage a tangible community asset. 8. It enlivens places where people work, which can improve employee morale, productivity and respect. 9. It creates supportive learning environments. It opens eyes—and minds! It attracts students to environments conducive to both learning and fun. 10. It raises public awareness about important community issues, such as environmental stewardship and respect for diversity. --From the Amherst Public Art Commission and the National Assembly of State Arts Agencies. The Amherst Public Art Commission Why Public Art for Amherst? Public art adds enormous value to the cultural, aesthetic and economic vitality of a community. It is now a well-accepted principle of urban design that public art contributes to a community’s identity, fosters community pride and a sense of belonging, and enhances the quality of life for its residents and visitors.