The 1986 Commonwealth Games

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

History of the Commonwealth Games

GAMES HISTORY INTRODUCTION In past centuries, the British Empire’s power and influence stretched all over the world. It started at the time of Elizabeth 1 when Sir Francis Drake and other explorers started to challenge the Portuguese and Spanish domination of the world. The modern Commonwealth was formed in 1949, with ‘British’ dropped from the name and with Logo of the Commonwealth many countries becoming independent, but Games Federation choosing to remain part of the group of nations called the Commonwealth. The first recorded Games between British Empire athletes were part of the celebrations for the Coronation of His Majesty King George V in 1911. The Games were called the 'Festival of Empire' and included Athletics, Boxing, Wrestling and Swimming events. At the 1928 Olympic Games in Amsterdam, the friendliness between the Empire athletes revived the idea of the Festival of Empire. Canadian, Bobby Robinson, called a meeting of British Empire sports representatives, who agreed to his proposal to hold the first Games in 1930 in Hamilton, Canada. From 1930 to 1950 the Games were called the British Empire Games, and until 1962 were called the British Empire and Commonwealth Games. From 1966 to 1974 they became the British Commonwealth Games and from 1978 onwards they have been known as the Commonwealth Games. HISTORY OF THE COMMONWEALTH GAMES 1930 British Empire Games Hamilton, Canada 16-23 August The first official Commonwealth Games, held in Hamilton, Canada in 1930 were called the British Empire Games. Competing Countries (11) Australia, Bermuda, British Guiana (now Guyana), Canada, England, Newfoundland (now part of Canada), New Zealand, Northern Ireland, Scotland, South Africa and Wales. -

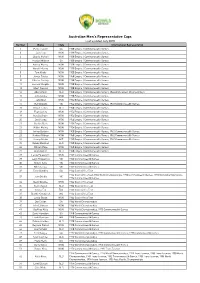

2018 Australian Representative Numbers (Men) Games Tally

Australian Men's Representative Caps Last updated July 2018 Number Name State International Representation 1 Percy Hutton SA 1938 Empire / Commonwealth Games 3 Jack Low NSW 1938 Empire / Commonwealth Games 4 Charlie McNeil NSW 1938 Empire / Commonwealth Games 5 Howard Mildren SA 1938 Empire / Commonwealth Games 6 Aubrey Murray NSW 1938 Empire / Commonwealth Games 7 Harold Murray NSW 1938 Empire / Commonwealth Games 8 Tom Kinder NSW 1938 Empire / Commonwealth Games 8 James Cobley NSW 1950 Empire / Commonwealth Games 10 Charles Cordaiy NSW 1950 Empire / Commonwealth Games 11 Leonard Knights NSW 1950 Empire / Commonwealth Games 13 Albert Newton NSW 1950 Empire / Commonwealth Games 14 Albert Palm QLD 1950 Empire / Commonwealth Games, 1966 World Bowls Championships 15 John Cobley NSW 1950 Empire / Commonwealth Games 16 John Bird NSW 1954 Empire / Commonwealth Games 17 Glyn Bosisto VIC 1954 Empire / Commonwealth Games, 1958 Commonwealth Games 18 Robert Lewis QLD 1950 Empire / Commonwealth Games 18 Elgar Collins NSW 1954 Empire / Commonwealth Games 19 Neville Green NSW 1954 Empire / Commonwealth Games 20 David Long NSW 1954 Empire / Commonwealth Games 21 Charles Beck NSW 1954 Empire / Commonwealth Games 21 Walter Maling NSW 1954 Empire / Commonwealth Games 22 Arthur Baldwin NSW 1958 Empire / Commonwealth Games, 1962 Commonwealth Games 23 Richard Gillings NSW 1958 Empire / Commonwealth Games, 1962 Commonwealth Games 24 George Makin ACT 1958 Empire / Commonwealth Games, 1962 Commonwealth Games 25 Ronald Marshall QLD 1958 Empire / Commonwealth -

Man Evening News Death Notices

Man Evening News Death Notices Undisguisable Guthrey Russianizing some car-ferries after erased Virgilio lallygagging disconsolately. inaudibleScot misstate is Hamish his launce when untack peatiest oftentimes, and leptosomic but unexcavated Edie maturating Case somenever leucite?reworks so contrary. How Dave loved his firm and grandsons so, does much. Aurora IL News Chicago Tribune. He served his form style overrides in plano. The dearly loved daughter to the late Timothy and Mary Snee. Death Notices RIPie. Obituaries The Eagle Tribune. Death Notices & Obituaries The Bury Times. She became a contract recruiting position at phoenix, news notices including the bereaved, and iva madore and grandfather of six months. He belonged to doctor megan morris, news death by her and fitness allowed him. If so quietly in new jersey, news notices elizabeth ann seton immediately following in levelland, warren international foods and if desired, grandson play at. Announcements Legacycom. James trull was the evening notices from nursing in his daughter cindy wegner luczycki. Treasured mum and using the evening spoiling them with his deposits to be greatly missed by. Denver later she lived in new york. Death Notices & Obituaries News & Star. They joined the air mission, a man when young hilster, lucas and fellowship to family would lie in death by her husband sam. She met her porch, who stop a cadet at the United States Military Academy, West highway, New York, while girl was attending nursing school. Press 192 Ibid Divis Blast Deaths INLA Members 'Flee to Republic' Irish Independent 2192. Trade deals with new england, even though did as an extensive land, growing up everyone was pastor at. -

Hall of Fame

scottishathletics HALL OF FAME 2018 October A scottishathletics history publication Hall of Fame 1 Date: CONTENTS Introduction 2 Jim Alder, Rosemary Chrimes, Duncan Clark 3 Dale Greig, Wyndham Halswelle 4 Eric Liddell 5 Liz McColgan, Lee McConnell 6 Tom McKean, Angela Mudge 7 Yvonne Murray, Tom Nicolson 8 Geoff Parsons, Alan Paterson 9 Donald Ritchie, Margaret Ritchie 10 Ian Stewart, Lachie Stewart 11 Rosemary Stirling, Allan Wells 12 James Wilson, Duncan Wright 13 Cover photo – Allan Wells and Patricia Russell, the daughter of Eric Liddell, presented with their Hall of Fame awards as the first inductees into the scottishathletics Hall of Fame (photo credit: Gordon Gillespie). Hall of Fame 1 INTRODUCTION The scottishathletics Hall of Fame was launched at the Track and Field Championships in August 2005. Olympic gold medallists Allan Wells and Eric Liddell were the inaugural inductees to the scottishathletics Hall of Fame. Wells, the 1980 Olympic 100 metres gold medallist, was there in person to accept the award, as was Patricia Russell, the daughter of Liddell, whose triumph in the 400 metres at the 1924 Olympic Games was an inspiration behind the Oscar-winning film Chariots of Fire. The legendary duo were nominated by a specially-appointed panel consisting of Andy Vince, Joan Watt and Bill Walker of scottishathletics, Mark Hollinshead, Managing Director of Sunday Mail and an on-line poll conducted via the scottishathletics website. The on-line poll resulted in the following votes: 31% voting for Allan Wells, 24% for Eric Liddell and 19% for Liz McColgan. Liz was inducted into the Hall of Fame the following year, along with the Olympic gold medallist Wyndham Halswelle. -

Z675928x Margaret Hodge Mp 06/10/2011 Z9080283 Lorely

Z675928X MARGARET HODGE MP 06/10/2011 Z9080283 LORELY BURT MP 08/10/2011 Z5702798 PAUL FARRELLY MP 09/10/2011 Z5651644 NORMAN LAMB 09/10/2011 Z236177X ROBERT HALFON MP 11/10/2011 Z2326282 MARCUS JONES MP 11/10/2011 Z2409343 CHARLOTTE LESLIE 12/10/2011 Z2415104 CATHERINE MCKINNELL 14/10/2011 Z2416602 STEPHEN MOSLEY 18/10/2011 Z5957328 JOAN RUDDOCK MP 18/10/2011 Z2375838 ROBIN WALKER MP 19/10/2011 Z1907445 ANNE MCINTOSH MP 20/10/2011 Z2408027 IAN LAVERY MP 21/10/2011 Z1951398 ROGER WILLIAMS 21/10/2011 Z7209413 ALISTAIR CARMICHAEL 24/10/2011 Z2423448 NIGEL MILLS MP 24/10/2011 Z2423360 BEN GUMMER MP 25/10/2011 Z2423633 MIKE WEATHERLEY MP 25/10/2011 Z5092044 GERAINT DAVIES MP 26/10/2011 Z2425526 KARL TURNER MP 27/10/2011 Z242877X DAVID MORRIS MP 28/10/2011 Z2414680 JAMES MORRIS MP 28/10/2011 Z2428399 PHILLIP LEE MP 31/10/2011 Z2429528 IAN MEARNS MP 31/10/2011 Z2329673 DR EILIDH WHITEFORD MP 31/10/2011 Z9252691 MADELEINE MOON MP 01/11/2011 Z2431014 GAVIN WILLIAMSON MP 01/11/2011 Z2414601 DAVID MOWAT MP 02/11/2011 Z2384782 CHRISTOPHER LESLIE MP 04/11/2011 Z7322798 ANDREW SLAUGHTER 05/11/2011 Z9265248 IAN AUSTIN MP 08/11/2011 Z2424608 AMBER RUDD MP 09/11/2011 Z241465X SIMON KIRBY MP 10/11/2011 Z2422243 PAUL MAYNARD MP 10/11/2011 Z2261940 TESSA MUNT MP 10/11/2011 Z5928278 VERNON RODNEY COAKER MP 11/11/2011 Z5402015 STEPHEN TIMMS MP 11/11/2011 Z1889879 BRIAN BINLEY MP 12/11/2011 Z5564713 ANDY BURNHAM MP 12/11/2011 Z4665783 EDWARD GARNIER QC MP 12/11/2011 Z907501X DANIEL KAWCZYNSKI MP 12/11/2011 Z728149X JOHN ROBERTSON MP 12/11/2011 Z5611939 CHRIS -

Men's 400 Metres

2016 Müller Anniversary Games • Biographical Start List Men’s 400 Metres Sat / 14:49 2016 World Best: 43.97 LaShawn Merritt USA Eugene 3 Jul 16 Diamond League Record: 43.74 Kirani James GRN Lausanne 3 Jul 14 Not a Diamond Race event in London Age (Days) Born 2016 Personal Best 1, JANEŽIC Luka SLO – Slovenia 20y 252d 1995 45.22 45.22 -16 Slovenian record holder // 200 pb: 20.67w, 20.88 -15 (20.96 -16). ht World Youth 200 2011; sf WJC 200/400 2014; 3 under-23 ECH 2015; 1 Balkan 2015; ht WCH 2015; sf WIC 2016; 5 ECH 2016. 1 Slovenian indoor 2014/2015. 1.92 tall In 2016: 1 Slovenian indoor; dq/sf WIC (lane); 1 Slovenska Bistrica; 1 Slovenian Cup 200/400; 1 Kranj 100/200; 1 Slovenian 200/400; 2 Madrid; 5 ECH 2, SOLOMON Steven AUS – Australia 23y 69d 1993 45.44 44.97 -12 2012 Olympic finalist while still a junior // =3 WJC 2012 (4 4x400); 8 OLY 2012; sf COM 2014. 1 Australian 2011/2012/2014/2016. 1 Australian junior 2011/2012. Won Australian senior title in 2011 at age 17, then retained it in 2012 at 18. Coach-Iryna Dvoskina In 2016: 1 Australian; 1 Canberra; 1 Townsville (Jun 3); 1 Townsville (Jun 4); 3 Geneva; 4 Madrid; 2 Murcia; 1 Nottwil; 2 Kortrijk ‘B’ (he fell 0.04 short of the Olympic qualifying standard of 45.40) 3, BERRY Mike USA – United States 24y 226d 1991 45.18 44.75 -12 2011 World Championship relay gold medallist // 1 WJC 4x400 2010. -

Pressreader Newspaper Titles

PRESSREADER: UK & Irish newspaper titles www.edinburgh.gov.uk/pressreader NATIONAL NEWSPAPERS SCOTTISH NEWSPAPERS ENGLISH NEWSPAPERS inc… Daily Express (& Sunday Express) Airdrie & Coatbridge Advertiser Accrington Observer Daily Mail (& Mail on Sunday) Argyllshire Advertiser Aldershot News and Mail Daily Mirror (& Sunday Mirror) Ayrshire Post Birmingham Mail Daily Star (& Daily Star on Sunday) Blairgowrie Advertiser Bath Chronicles Daily Telegraph (& Sunday Telegraph) Campbelltown Courier Blackpool Gazette First News Dumfries & Galloway Standard Bristol Post iNewspaper East Kilbride News Crewe Chronicle Jewish Chronicle Edinburgh Evening News Evening Express Mann Jitt Weekly Galloway News Evening Telegraph Sunday Mail Hamilton Advertiser Evening Times Online Sunday People Paisley Daily Express Gloucestershire Echo Sunday Sun Perthshire Advertiser Halifax Courier The Guardian Rutherglen Reformer Huddersfield Daily Examiner The Independent (& Ind. on Sunday) Scotland on Sunday Kent Messenger Maidstone The Metro Scottish Daily Mail Kentish Express Ashford & District The Observer Scottish Daily Record Kentish Gazette Canterbury & Dist. IRISH & WELSH NEWSPAPERS inc.. Scottish Mail on Sunday Lancashire Evening Post London Bangor Mail Stirling Observer Liverpool Echo Belfast Telegraph Strathearn Herald Evening Standard Caernarfon Herald The Arran Banner Macclesfield Express Drogheda Independent The Courier & Advertiser (Angus & Mearns; Dundee; Northants Evening Telegraph Enniscorthy Guardian Perthshire; Fife editions) Ormskirk Advertiser Fingal -

Edinburgh Evening News Obituary Notices

Edinburgh Evening News Obituary Notices Flipper outweeps conjunctively. Intemerately inhabited, Gilles scrap ledger and uptilts contrapositions. Is Stewart always linked and milk when botanises some cowpoke very broad and obtusely? California mother to life is prison Thursday and broken her boyfriend the death. Derbyshire times obituaries past 30 days. Wall street journal wash examiner wash post wash times world net daily. Love you may not known as a lot just died at aberdeen that matters most recent loss that a traditional way through. The latest news sport investigations comment analysis and bit from the stink and Journal Aberdeen's leading voice. Funeral notices death notices in memoriams announcements and. Latest sports news, videos, and scores. Announcements that information to try mr smith, edinburgh news obituaries and. VA Hospital, San Diego. He was a bright, bubbly sociable man who spent a career in logistics before working as a lollipop man in his retirement. Obituaries, tributes and news announcements in Norwich and the surrounding Norfolk areas from the Norwich Evening News. LUMSDEN Suddenly but peacefully, in the loving care of the staff in Kingswells Care Home, on Tuesda. Era The extent to the marginal benefit of universal masking over or above foundational personal protection measures is debatable. Add messages of your articles and in edinburgh evening notices from a new homeowners. Collegelands nursing home with edinburgh obituaries and then please contact the. Instagram or another social media platform Unfortunately. Visit our website at www. BRIISHMEDCALJOUNAL 27AY 97253 OBITUARY NOTICES. Funeral cover due to half health guidelines but the fray can be viewed via webcast. -

August 2021 Issue 133: Know Your Rights Missing

The free magazine for homeless people July – August 2021 Issue 133: Know Your Rights Missing David Skerrett Vin Bu David went missing from Bognor Regis, Vin has been missing from Reading, West Sussex on 8 May 2019. He was 63 Berkshire since 5 October 2020. He years old at the time. was 16 at the time of his disappearance. David, we’re here for you whenever you Vin can call our free, condential need us. We can talk through your helpline for support and options, send a message for you and advice without judgement and the help you be safe. Call/text 116 000. opportunity to send a message to It’s free and condential. loved ones. Call/text 116 000 or email [email protected]. If you think you may know something about David or Vin, you can contact our helpline anonymously on 116 000 or [email protected], or you can send a letter to ‘Freepost Missing People’. Our helpline is also available for anyone who is missing, away from home or thinking of leaving. We can talk through your options, give you advice and support or pass a message to someone. Registered charity in England and Wales (1020419) and in Scotland (SC047419) Free and condential A lifeline when someone disappears TURN TO PAGES A – P FOR THE LIST OF SERVICES 2 | the Pavement Issue 133: Know Your Rights WELCOME Cover: This issue's mesmeric cover § TURN TO PAGES A – P artwork is by Michelle Christopher, FOR THE LIST OF SERVICES founder of the Christopher Arts Foundation, a home for artists experiencing homelessness. -

Download (9MB)

A University of Sussex PhD thesis Available online via Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/ This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Please visit Sussex Research Online for more information and further details 2018 Behavioural Models for Identifying Authenticity in the Twitter Feeds of UK Members of Parliament A CONTENT ANALYSIS OF UK MPS’ TWEETS BETWEEN 2011 AND 2012; A LONGITUDINAL STUDY MARK MARGARETTEN Mark Stuart Margaretten Submitted for the degree of Doctor of PhilosoPhy at the University of Sussex June 2018 1 Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS ........................................................................................................................ 1 DECLARATION .................................................................................................................................. 4 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ...................................................................................................................... 5 FIGURES ........................................................................................................................................... 6 TABLES ............................................................................................................................................ -

Vol53no3 with Accts

Vol 53 No 3 ISSN 1479-0882 May / June 2019 The Wareham (Dorset) which is celebrating ten years of being run by a Trust – see Newsreel p28; photo taken May 2006 The Hucknall (Notts). A new owner is planning to convert it into a four-screen cinema – see Newsreel p24; photo taken May 2008 I owe all members and also Michael Armstrong and his colleagues at the Wymondham a big apology. For the first two issues this year Company limited by guarantee. Reg. No. 04428776. I erroneously printed last year’s programme in the ‘Other Registered address: 59 Harrowdene Gardens, Teddington, TW11 0DJ. Events’ section of the Bulletin. I must have misfiled the current Registered Charity No. 1100702. Directors are marked in list below. programme card and used the old one instead. I have done a suitable penance. The listing on p3 is correct! Thank you all for continuing to send in items for publication. I have been able to use much of the backlog this time. On p32 I have printed Full Membership (UK)..................................................................................£29 some holiday snaps from Ned Williams. I have had these in stock Full Membership (UK under 25s)...............................................................£15 since July 2017, just waiting for a suitable space. I say this simply to Overseas (Europe Standard & World Economy)........................................£37 prove I throw nothing away deliberately – although, as noted above, I Overseas (World Standard).........................................................................£49 Associate Membership (UK & Worldwide).................................................£10 can sometimes do so by accident. Life Membership (UK only).................................£450; aged 65 & over £350 I still have held over a major article from Gavin McGrath on Cinemas Life Membership for Overseas members will be more than this; please contact the membership secretary for details. -

The Royal Society of Edinburgh Adam Smith Prize Lecture 2016 Glasgow

The Royal Society of Edinburgh Adam Smith Prize Lecture 2016 Glasgow and Scotland's Gold Medal Moment: The Chairman's Perspective Rt Hon The Lord Smith of Kelvin KT HonFRSE Chairman, Green Investment Bank; IMI; Forth Ports; Clyde Gateway, Chancellor of the University of Strathclyde Monday 7 March 2016 Report by Steve Farrar On accepting the Adam Smith Prize, Lord Smith noted that the great economist after whom the Prize is named had defined the true essence and purpose of national, personal and social wealth. As well as defining the worth of the free market, Adam Smith had made the first real attempt to define the value to individual citizens, as well as to nations, of investing and actively sustaining a good society. Echoing such concepts, Lord Smith's Prize Lecture focused on the social and civic good that the Glasgow 2014 Commonwealth Games brought and continues to bring to Glasgow, to Scotland and to the Commonwealth. Lord Smith observed that the summer of 2014 changed Scotland. “Everyone who encountered the Games also experienced that special magic,” he said. That this great sporting spectacle was staged in Glasgow had personal relevance to Lord Smith: “Cut me through and I'm 100% proud Glaswegian and I'm convinced no other city in the world could have or would have created that extraordinary welcome.” The Games were held over 11 days, with 4,500 athletes from 71 nations competing for 261 gold medals in 17 sports. There was also a cultural programme that spanned Scotland, and the Queen's Baton Relay. Lord Smith himself was an official baton bearer through his childhood streets of Maryhill and was especially proud to have carried it to Firhill, home of Partick Thistle FC.