1986 Commonwealth Games ------The Year of the Boycott

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

History of the Commonwealth Games

GAMES HISTORY INTRODUCTION In past centuries, the British Empire’s power and influence stretched all over the world. It started at the time of Elizabeth 1 when Sir Francis Drake and other explorers started to challenge the Portuguese and Spanish domination of the world. The modern Commonwealth was formed in 1949, with ‘British’ dropped from the name and with Logo of the Commonwealth many countries becoming independent, but Games Federation choosing to remain part of the group of nations called the Commonwealth. The first recorded Games between British Empire athletes were part of the celebrations for the Coronation of His Majesty King George V in 1911. The Games were called the 'Festival of Empire' and included Athletics, Boxing, Wrestling and Swimming events. At the 1928 Olympic Games in Amsterdam, the friendliness between the Empire athletes revived the idea of the Festival of Empire. Canadian, Bobby Robinson, called a meeting of British Empire sports representatives, who agreed to his proposal to hold the first Games in 1930 in Hamilton, Canada. From 1930 to 1950 the Games were called the British Empire Games, and until 1962 were called the British Empire and Commonwealth Games. From 1966 to 1974 they became the British Commonwealth Games and from 1978 onwards they have been known as the Commonwealth Games. HISTORY OF THE COMMONWEALTH GAMES 1930 British Empire Games Hamilton, Canada 16-23 August The first official Commonwealth Games, held in Hamilton, Canada in 1930 were called the British Empire Games. Competing Countries (11) Australia, Bermuda, British Guiana (now Guyana), Canada, England, Newfoundland (now part of Canada), New Zealand, Northern Ireland, Scotland, South Africa and Wales. -

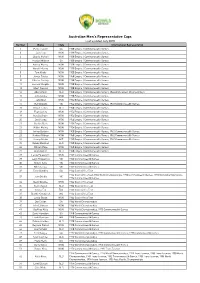

2018 Australian Representative Numbers (Men) Games Tally

Australian Men's Representative Caps Last updated July 2018 Number Name State International Representation 1 Percy Hutton SA 1938 Empire / Commonwealth Games 3 Jack Low NSW 1938 Empire / Commonwealth Games 4 Charlie McNeil NSW 1938 Empire / Commonwealth Games 5 Howard Mildren SA 1938 Empire / Commonwealth Games 6 Aubrey Murray NSW 1938 Empire / Commonwealth Games 7 Harold Murray NSW 1938 Empire / Commonwealth Games 8 Tom Kinder NSW 1938 Empire / Commonwealth Games 8 James Cobley NSW 1950 Empire / Commonwealth Games 10 Charles Cordaiy NSW 1950 Empire / Commonwealth Games 11 Leonard Knights NSW 1950 Empire / Commonwealth Games 13 Albert Newton NSW 1950 Empire / Commonwealth Games 14 Albert Palm QLD 1950 Empire / Commonwealth Games, 1966 World Bowls Championships 15 John Cobley NSW 1950 Empire / Commonwealth Games 16 John Bird NSW 1954 Empire / Commonwealth Games 17 Glyn Bosisto VIC 1954 Empire / Commonwealth Games, 1958 Commonwealth Games 18 Robert Lewis QLD 1950 Empire / Commonwealth Games 18 Elgar Collins NSW 1954 Empire / Commonwealth Games 19 Neville Green NSW 1954 Empire / Commonwealth Games 20 David Long NSW 1954 Empire / Commonwealth Games 21 Charles Beck NSW 1954 Empire / Commonwealth Games 21 Walter Maling NSW 1954 Empire / Commonwealth Games 22 Arthur Baldwin NSW 1958 Empire / Commonwealth Games, 1962 Commonwealth Games 23 Richard Gillings NSW 1958 Empire / Commonwealth Games, 1962 Commonwealth Games 24 George Makin ACT 1958 Empire / Commonwealth Games, 1962 Commonwealth Games 25 Ronald Marshall QLD 1958 Empire / Commonwealth -

Hall of Fame

scottishathletics HALL OF FAME 2018 October A scottishathletics history publication Hall of Fame 1 Date: CONTENTS Introduction 2 Jim Alder, Rosemary Chrimes, Duncan Clark 3 Dale Greig, Wyndham Halswelle 4 Eric Liddell 5 Liz McColgan, Lee McConnell 6 Tom McKean, Angela Mudge 7 Yvonne Murray, Tom Nicolson 8 Geoff Parsons, Alan Paterson 9 Donald Ritchie, Margaret Ritchie 10 Ian Stewart, Lachie Stewart 11 Rosemary Stirling, Allan Wells 12 James Wilson, Duncan Wright 13 Cover photo – Allan Wells and Patricia Russell, the daughter of Eric Liddell, presented with their Hall of Fame awards as the first inductees into the scottishathletics Hall of Fame (photo credit: Gordon Gillespie). Hall of Fame 1 INTRODUCTION The scottishathletics Hall of Fame was launched at the Track and Field Championships in August 2005. Olympic gold medallists Allan Wells and Eric Liddell were the inaugural inductees to the scottishathletics Hall of Fame. Wells, the 1980 Olympic 100 metres gold medallist, was there in person to accept the award, as was Patricia Russell, the daughter of Liddell, whose triumph in the 400 metres at the 1924 Olympic Games was an inspiration behind the Oscar-winning film Chariots of Fire. The legendary duo were nominated by a specially-appointed panel consisting of Andy Vince, Joan Watt and Bill Walker of scottishathletics, Mark Hollinshead, Managing Director of Sunday Mail and an on-line poll conducted via the scottishathletics website. The on-line poll resulted in the following votes: 31% voting for Allan Wells, 24% for Eric Liddell and 19% for Liz McColgan. Liz was inducted into the Hall of Fame the following year, along with the Olympic gold medallist Wyndham Halswelle. -

Men's 400 Metres

2016 Müller Anniversary Games • Biographical Start List Men’s 400 Metres Sat / 14:49 2016 World Best: 43.97 LaShawn Merritt USA Eugene 3 Jul 16 Diamond League Record: 43.74 Kirani James GRN Lausanne 3 Jul 14 Not a Diamond Race event in London Age (Days) Born 2016 Personal Best 1, JANEŽIC Luka SLO – Slovenia 20y 252d 1995 45.22 45.22 -16 Slovenian record holder // 200 pb: 20.67w, 20.88 -15 (20.96 -16). ht World Youth 200 2011; sf WJC 200/400 2014; 3 under-23 ECH 2015; 1 Balkan 2015; ht WCH 2015; sf WIC 2016; 5 ECH 2016. 1 Slovenian indoor 2014/2015. 1.92 tall In 2016: 1 Slovenian indoor; dq/sf WIC (lane); 1 Slovenska Bistrica; 1 Slovenian Cup 200/400; 1 Kranj 100/200; 1 Slovenian 200/400; 2 Madrid; 5 ECH 2, SOLOMON Steven AUS – Australia 23y 69d 1993 45.44 44.97 -12 2012 Olympic finalist while still a junior // =3 WJC 2012 (4 4x400); 8 OLY 2012; sf COM 2014. 1 Australian 2011/2012/2014/2016. 1 Australian junior 2011/2012. Won Australian senior title in 2011 at age 17, then retained it in 2012 at 18. Coach-Iryna Dvoskina In 2016: 1 Australian; 1 Canberra; 1 Townsville (Jun 3); 1 Townsville (Jun 4); 3 Geneva; 4 Madrid; 2 Murcia; 1 Nottwil; 2 Kortrijk ‘B’ (he fell 0.04 short of the Olympic qualifying standard of 45.40) 3, BERRY Mike USA – United States 24y 226d 1991 45.18 44.75 -12 2011 World Championship relay gold medallist // 1 WJC 4x400 2010. -

The Royal Society of Edinburgh Adam Smith Prize Lecture 2016 Glasgow

The Royal Society of Edinburgh Adam Smith Prize Lecture 2016 Glasgow and Scotland's Gold Medal Moment: The Chairman's Perspective Rt Hon The Lord Smith of Kelvin KT HonFRSE Chairman, Green Investment Bank; IMI; Forth Ports; Clyde Gateway, Chancellor of the University of Strathclyde Monday 7 March 2016 Report by Steve Farrar On accepting the Adam Smith Prize, Lord Smith noted that the great economist after whom the Prize is named had defined the true essence and purpose of national, personal and social wealth. As well as defining the worth of the free market, Adam Smith had made the first real attempt to define the value to individual citizens, as well as to nations, of investing and actively sustaining a good society. Echoing such concepts, Lord Smith's Prize Lecture focused on the social and civic good that the Glasgow 2014 Commonwealth Games brought and continues to bring to Glasgow, to Scotland and to the Commonwealth. Lord Smith observed that the summer of 2014 changed Scotland. “Everyone who encountered the Games also experienced that special magic,” he said. That this great sporting spectacle was staged in Glasgow had personal relevance to Lord Smith: “Cut me through and I'm 100% proud Glaswegian and I'm convinced no other city in the world could have or would have created that extraordinary welcome.” The Games were held over 11 days, with 4,500 athletes from 71 nations competing for 261 gold medals in 17 sports. There was also a cultural programme that spanned Scotland, and the Queen's Baton Relay. Lord Smith himself was an official baton bearer through his childhood streets of Maryhill and was especially proud to have carried it to Firhill, home of Partick Thistle FC. -

Commonwealth Games Canada Alumni Newsletter - November 2019 / Jeux Du Commonwealth Canada Communiqué Des Anciens - Novembre 2019

Commonwealth Games Canada Alumni Newsletter - November 2019 / Jeux du Commonwealth Canada Communiqué des anciens - novembre 2019 Subscribe Past Issues Translate RSS (le français à suivre) View this email in your browser Commonwealth Games Canada ALUMNI COMMUNIQUE Issue 6 - November 2019 HAVE YOU JOINED COMMONWEALTH GAMES CANADA'S ALUMNI PROGRAM YET? To date, approximately 3,000 Canadian athletes have competed in the Commonwealth Games. Thousands more have attended the Games as officials or given their time as volunteers. Over 200 CGC SportWORKS Officers have taken part in sport development initiatives in Canada and throughout the Commonwealth. CGC is proud to have been a part of so many lives and we would cherish the opportunity to continue our relationship through the CGC Alumni Program! Why should you become a CGC Alumni Program member? Being a CGC Alumni Program member allows you to: Stay in touch with other CGC alumni. Receive regular CGC Alumni Newsletters containing news & information about the Commonwealth sport movement in Canada and abroad. Become a mentor and contribute to the success of current and future CGC alumni. Receive invitations to CGC Alumni events happening in your area. Receive exclusive access and offers on CGC/Team Canada clothing, Commonwealth sport events tickets and packages, etc. Have a chance to win an all-inclusive, VIP trip for two to the next Commonwealth Games! Receive exclusive CGC Alumni discounts! As a Commonwealth Games Canada Alumni Program member, you are entitled to the following discounts: 20% DISCOUNT AT ALL RUNNING ROOM STORES REMINDER: If you are a CGC Alumni Program member and have not yet received your Running Room discount card, please confirm your mailing address so we can send it to you. -

Hotel Demand Before, During, and After Sports Events: Evidence from Charlotte, North Carolina

HOTEL DEMAND BEFORE, DURING, AND AFTER SPORTS EVENTS: EVIDENCE FROM CHARLOTTE, NORTH CAROLINA CRAIG A. DEPKEN II and E. FRANK STEPHENSON This paper uses daily hotel occupancy data to examine the effects of a wide variety of political and sporting events on the hotel room market of Charlotte, North Carolina from 2005 to 2014. Two political conventions and NASCAR auto races are associated with large increases in hotel occupancy, prices, and revenue, but many other events have no discernable effect on Charlotte’s hotel market. The results also indicate that occupancy effects before or after most events are modest at best. Back-of-the-envelope calculations show incremental hotel-tax receipts fall short of the debt service incurred in constructing and maintaining the city’s sports venues. (JEL H71, Z23, Z28) I. INTRODUCTION days after the event. We test whether there are statistically significant impacts on hotel demand, As the academic literature on the economic hotel prices, and hotel revenue, during the days impact of sports or other events is vast, it is worth leading up to or following the events included in calling immediate attention to this paper’s contri- our analysis. This provides insight into the eco- butions. This paper is the first to use daily hotel nomic effects of sports events and any external occupancy data over a long period to investigate benefits or external costs they may generate. the net impacts of political and sporting events on We distinguish between hotels that are close hotel demand, room prices, and total daily hotel to the Charlotte venues, those that are at an inter- room revenue in a large city in the United States. -

Commonwealth Games: Friendly Rivalry

Parliament of Australia Department of Parliamentary Services RESEARCH PAPER SERIES, 2013–14 6 November 2013 Commonwealth Games: friendly rivalry Dr Rhonda Jolly Social Policy Section Executive summary • Elite athletes from the Commonwealth meet every four years to compete in the multi-sport event known as the Commonwealth Games. • While the Commonwealth Games boasts many similarities to the Olympics, it differs in the more relaxed and ‘friendly’ spirit of competition, which is a highlight of most events. • The spirit of friendship has not always prevailed, however, and there have been serious rifts between Commonwealth nations that have manifested themselves in boycotts of the Games. While these have threatened at times to dissolve, or seriously weaken the Commonwealth, solutions have always been found and the Commonwealth and its Games have endured. • Australia was one of a group of nations that first participated in competition between Britain and its colonies in 1911; it has participated in the Games in all its forms since that time. It is acknowledged as the most successful of the Commonwealth nations in this sporting competition—winning over 200 more medals than its nearest rival. • Australian cities have hosted the Games four times. While there have been some hiccoughs in the staging of each event—some social, and some economic—Sydney, Perth and Brisbane have all received accolades and Melbourne was praised as ‘the best’ following the 2006 Games. • In 2018 Australia will host another Commonwealth Games—on Queensland’s Gold Coast. • This paper looks back at how the Games came to be, Australia’s experience of staging the event and contemplates how the Gold Coast will deal with that legacy and surmount perceived and unexpected complications that will inevitably surface before the 2018 Games’ Opening Ceremony. -

Sajal Philatelics Cover Auctions Sale No. 301 Thu 11 Nov 2010 1 Lot No

Lot No. Estimate 1929 UNIVERSAL POSTAL UNION CONGRESS 1 Union Postale Universelle Congres de Londres 1929 DISPLAY FDC with Postal Union Congress London CDS. The same wording is in a logo on the flap on reverse. Only catalogued as plain FDC. UA (see photo) £1,250 1935 SILVER JUBILEE 2 Francis Field Display FDC with Sutton Coldfield CDS. Cat £400. AT (see photo) £120 1937 CORONATION 3 Unusual illustration (large maroon & green crown) FDC with Clacton on Sea M/C. Cat £30. AT £15 1940 CENTENARY 4 Set on pair of unusual illustration FDCs with Adhesive Stamp Centenary Bournmouth special H/S. Cat £50. AT £20 1946 VICTORY 5 Ronald Johnson Display FDC with Abbeville Road Clapham reg CDS. Cat £40. AP £12 1953 CORONATION 6 1/3d on Qantas FDC with London F.S. slogan "Long Live the Queen" + "Coronation Day Air Mail Flight Cocos Islands" cachet. AT £6 7 1/3d on Qantas FDC with London F.S. slogan "Long Live the Queen" + "Coronation Day Air Mail Flight Karachi" cachet. AT £6 8 1/3d on Qantas FDC with London F.S. slogan "Long Live the Queen" + "Coronation Day Air Mail Flight Mauritius" cachet. Neatly slit open at top. AT £6 9 1/3d on Qantas FDC with London F.S. slogan "Long Live the Queen" + "Coronation Day Air Mail Flight Singapore" cachet. AT £6 10 1/6d on Qantas FDC with London F.S. slogan "Long Live the Queen" + "Coronation Day Air Mail Flight Fiji" cachet. Neatly slit open at top. AT £6 11 1/6d on Qantas FDC with London F.S. -

Silver Ferns Vitality Netball World Cup Liverpool Media Guide 2019 July 2019

VITALITY NETBALL WORLD CUP LIVERPOOL 2019 MEDIAGUIDE MEDIA MEDIA RESOURCES INFORMATON CONTENTS Media Contacts / 4 Media Information / 5 Venue Map / 6 Draw / 9 Silver Ferns Team / 15 Silver Ferns Management / 30 NZ Umpires / 31 Sponsors / 32 Silver Ferns History / 34 World Ranking / 35 Head to Head Stats / 36 World Netball Championship Placings / 47 Through the Years / 48 Silver Ferns Captains and Coaches / 62 High Performance / 64 MEDIA INFORMATION VITALITY NETBALL WORLD CUP LIVERPOOL 2019 5 MEDIA INFORMATON MEDIA MEDIA CONTACTS INFORMATION All Silver Ferns matches will be played at M&S Bank Arena, Liverpool. SILVER FERNS IN LIVERPOOL Kerry Manders (UK based) Post-match Mixed Zone media opportunities will be available after all Silver Ferns Test matches. Head of Communications and Marketing, Daily media updates will be sent out. Media, Government Relations Sign up to our mail out list by emailing [email protected] +64 21 410 970 SILVER FERNS IN NZ John Whiting (NNZ based) Communications and Channel Manager +64 27 468 8104 NETBALL WORLD CUP Jennifer Gibbon Digital Content & Marketing Officer [email protected] +44 1509 277 902 | +44 7458 126 925 PHOTOGRAPHY Official Photographer: Silver Ferns Michael Bradley Photography Michael Bradley, [email protected] M&S BANK ARENA LIVERPOOL ADDRESS: KING’S DOCK, PORT OF LIVERPOOL, 16 MONARCHS QUAY, LIVERPOOL L3 4FP, UK LIME ST DRAW LIME ST JAMES ST WHITECHAPEL LORD ST LORD ST CHURCH ST SOUTH JOHN ST PARADISE ST PARADISE CENTRAL HANOVER ST THOMAS STEERS WAY ROYAL SALTHOUSE QUAY ALBERT -

Senior Championships Results 130609

Welsh Athletics Senior T F Outdoor Championships Saturday 13th June 2009 Cardiff International Sports Stadium T31 - Senior Women - 100m - Final 0.00 All Comers Heather OAKES - England - 13.27 1984 Record Sallyanne SHORT - Torfaen AC - 11.39 1992 CBP Michelle PROBERT, Sallyanne SHORT - Sale Harriers, Torfaen AC - 11.3w 1980, 1989 2008 Champion Lucy EVANS - Sale Harriers - 12.19 -2.0 m/s Pos Bib Athlete Club Perf Comments 1 8 Elaine O'NEILL (W) U23W Woodford Green & Essex L 11.91 2 3 Lucy EVANS (W) SW Sale Harriers 12.13 3 7 Mica MOORE (W) U17W Cardiff AAC 12.33 4 9 Hannah PENDLEBURY (W) U20W Deeside AAC 12.42 5 13 Rebecca WILLIAMS (W) U23W Newport Harriers 12.66 6 10 Sarah POLE (W) U20W Neath Harriers 12.88 7 5 Laura LANGOWSKI SW Coventry Godiva H 13.15 8 1 Lolita BYFIELD-MOORE (W) SW Cardiff AAC 13.78 T22 - Senior Women - 100m - Heats 0.00 All Comers Heather OAKES - England - 13.27 1984 Record Sallyanne SHORT - Torfaen AC - 11.39 1992 CBP Michelle PROBERT, Sallyanne SHORT - Sale Harriers, Torfaen AC - 11.3w 1980, 1989 2008 Champion Lucy EVANS - Sale Harriers - 12.19 -0.7 m/s Ht 1 of 2 Pos Bib Athlete Club Perf Comments 1 8 Elaine O'NEILL (W) U23W Woodford Green & Essex L 12.14 Q 2 13 Rebecca WILLIAMS (W) U23W Newport Harriers 12.46 Q 3 9 Hannah PENDLEBURY (W) U20W Deeside AAC 12.53 4 1 Lolita BYFIELD-MOORE (W) SW Cardiff AAC 13.34 5 12 Amber VINCENT (W) U20W Cardiff AAC 13.35 T22 - Senior Women - 100m - Heats 0.00 All Comers Heather OAKES - England - 13.27 1984 Record Sallyanne SHORT - Torfaen AC - 11.39 1992 CBP Michelle PROBERT, Sallyanne -

Sajal Philatelics Cover Auctions Sale No. 272 Thu 19 Jun 2008 1 Lot No

Lot No. Estimate 1935 SILVER JUBILEE 1 Forgery of Westminster Stamp Co. illustrated FDC with London SW1 CDS. (Cat £550 as genuine) £24 2 Plain FDC with Croydon Aerodrome reg CDS. Neatly slit open at right. Cat £75. Neat AW £20 1937 CORONATION 3 Illustrated FDC (George VI in uniform) with Ogmore, Bridgend CDS. Cat £30. UA £15 1940 CENTENARY 4 1d value only on 1940 reprinted mulready cover with Adhesive Stamp Centenary Bournemouth special H/S. Neat AW £4 5 1d, 2d, 2½ d & 3d on Kenmore Stamp Company Display FDC with Brighton and Hove CDS. AT £4 1946 VICTORY 6 Illustrated FDC with Musselburgh M/C. Neatly slit open at top. Cat £40. AT £15 1948 SILVER WEDDING 7 2½ d value only on illustrated FDC with Halifax CDS. Cat £20. AW £5 1948 CHANNEL IS LIBERATION 8 Illustrated FDC with Jersey M/C. Cat £25. AP £12 9 Illustrated FDC with St Peter Port Guernsey CDS. Cat £35. AP £15 10 White's Stamp Shop Hertford pair of FDCs with one value on each with Hertford CDS. Cat £30. AP £10 1948 OLYMPIC GAMES 11 Illustrated FDC with Olympic Games Wembley slogan. Neatly slit open at top. Cat £50. AT £25 1949 UNIVERSAL POSTAL UNION 12 Blocks of 4 on pair of BPA/PTA illustrated FDCs with Heswall, Wirral CDS. Cat £70 as single set. AW £30 1953 CORONATION 13 1/6d value only on Qantas Coronation FDC with London F.S.slogan "Long Live the Queen" + Coronation Day Air Mail Flight cachet. Cat £25. AT £12 14 2½ d value only on BPA/PTS FDC with London W1 slogan "Long Live the Queen".