Arab Satellite Television in Italy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Universidad Católica De Santiago De Guayaquil Facultad De Educación Técnica Para El Desarrollo Carrera De Ingeniería En Telecomunicaciones

UNIVERSIDAD CATÓLICA DE SANTIAGO DE GUAYAQUIL FACULTAD DE EDUCACIÓN TÉCNICA PARA EL DESARROLLO CARRERA DE INGENIERÍA EN TELECOMUNICACIONES TEMA: Análisis del desempeño de la red móvil 4G LTE de datos en interiores de edificios utilizando la tecnología QCELL AUTOR: Blacio Moreno, Laura Angelina Trabajo de Titulación previo a la obtención del título de INGENIERA EN TELECOMUNICACIONES TUTOR: Ruilova Aguirre, Maria Luzmila Guayaquil, Ecuador 6 de marzo del 2018 UNIVERSIDAD CATÓLICA DE SANTIAGO DE GUAYAQUIL FACULTAD DE EDUCACIÓN TÉCNICA PARA EL DESARROLLO CARRERA DE INGENIERÍA EN TELECOMUNICACIONES CERTIFICACIÓN Certificamos que el presente trabajo fue realizado en su totalidad por la Srta. Blacio Moreno, Laura Angelina como requerimiento para la obtención del título de INGENIERA EN TELECOMUNICACIONES. TUTOR ________________________ Ruilova Aguirre, Maria Luzmila DIRECTOR DE CARRERA ________________________ Heras Sánchez, Miguel Armando Guayaquil, a los 6 días del mes de marzo del año 2018 UNIVERSIDAD CATÓLICA DE SANTIAGO DE GUAYAQUIL FACULTAD DE EDUCACIÓN TÉCNICA PARA EL DESARROLLO CARRERA DE INGENIERÍA EN TELECOMUNICACIONES DECLARACIÓN DE RESPONSABILIDAD Yo, Blacio Moreno, Laura Angelina DECLARO QUE: El trabajo de titulación “Análisis del desempeño de la red móvil 4G LTE de datos en interiores de edificios utilizando la tecnología QCELL” previo a la obtención del Título de Ingeniera en Telecomunicaciones, ha sido desarrollado respetando derechos intelectuales de terceros conforme las citas que constan en el documento, cuyas fuentes se incorporan -

Harrold on Silverstein, 'Algeria in France: Transpolitics, Race, and Nation'

H-Gender-MidEast Harrold on Silverstein, 'Algeria in France: Transpolitics, Race, and Nation' Review published on Friday, September 1, 2006 Paul A. Silverstein. Algeria in France: Transpolitics, Race, and Nation. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2004. x + 298 pp. $23.95 (paper), ISBN 978-0-253-21712-7; $49.95 (cloth), ISBN 978-0-253-34451-9. Reviewed by Deborah Harrold (Department of Political Science, Bryn Mawr College) Published on H-Gender-MidEast (September, 2006) Colonial Categories in Postmodern Politics: Algerian Berbers in France Anthropologist Paul Silverstein has written an impressive and engrossing account of the contemporary articulation and deployment of identity, turning on the postcolonial deployment of colonial categories in the metropole. The work is a valuable corrective to ubiquitous binaries: nation/globalization, citizen/immigrant, assimilation/cultural refusal. His accounts of individual trajectories, organizational strategies, and state policies contribute to a particularly fine understanding of the choices, strategies, and tactics available to global subalterns. Silverstein's fieldwork in contemporary France examines the reinvestment in colonial categories of Berber identity and the redeployment of these identities as one strategy of identity for Kabyle Algerians in France. Berber identity, he suggests, is an Algerian and North African identity that is an alternate, parallel, or supplementary choice to Islamic identity, poised both against and with a French identity; a French identity that beckons, promises, -

Estudio Del Servicio De Internet En Colombia

Estudios Económicos Sectoriales Estudio del Servicio de Internet en Colombia Diciembre 2015 Estudio preparado por Grupo de Estudios Económicos 1 Esta obra está bajo una Licencia Creative Commons Atribución-NoComercial- SinDerivadas 2.5 Colombia. Usted es libre de: Compartir - copiar, distribuir, ejecutar y comunicar públicamente la obra Bajo las condiciones siguientes: Atribución — Debe reconocer los créditos de la obra de la manera especificada por el autor o el licenciante. Si utiliza parte o la totalidad de esta investigación tiene que especificar la fuente. No Comercial — No puede utilizar esta obra para fines comerciales. Sin Obras Derivadas — No se puede alterar, transformar o generar una obra derivada a partir de esta obra. Los derechos derivados de usos legítimos u otras limitaciones reconocidas por la ley no se ven afectados por lo anterior. Este documento fue resultado de la investigación desarrollada por: Aura García Pabón, Yesica Juliana Henao Gutierrez, José Alejandro Rodríguez, Jacobo Campo Robledo y Juan Pablo Herrera. El análisis presentado y las opiniones expuestas en el presente documento son responsabilidad exclusiva del Grupo de Estudios Económicos y no representa la posición de la Superintendencia de Industria y Comercio en la materia. Para cualquier duda, sugerencia, corrección o comentario, escribir a: [email protected]. 2 Este estudio fue posible gracias al Fondo Regional para la Prosperidad del Gobierno del Reino Unido en Latinoamérica. Un agradecimiento especial a Caterin Estrada, Encargada Regional de Economías Abiertas para Latinoamérica de la Embajada Británica, por su apoyo a este Proyecto. 3 Estudio del Servicio de Internet en Colombia Grupo de Estudios Económicos Superintendencia de Industria y Comercio. -

Edinburgh University Press Post-Beur Cinema

1. INTRODUCTION: FROM IMMIGRANT CINEMA TO NATIONAL CINEMA Press In September 2010, Maghrebi-French filmmaker Rachid Bouchareb’s seventh feature film, Hors-la-loi, a gangster film set against the backdrop of the Algerian war for independence, was released across cinemas in France. Made for a budget of €20m, released onUniversity more than 400 prints and starring Jamel Debbouze – a French-born actor of Moroccan immigrant parents and one of French cinema’s biggest stars – Hors-la-loi enjoyed the kind of distribution and marketing conditions reserved for onlyCinema the most high-profile French main- stream productions. The film aimed to capitalise on the success of Bouchareb’s Second World War epic, Indigènes (2006), which attracted over three million spectators in France and received an Academy Award nomination for best foreign film (admittedly as an Algerian rather than French film). If Indigènes’ message to its French audience was simultaneously confrontational and con- ciliatory, holdingEdinburgh successive French governments to account for freezing the pensions of North African colonial soldiers at the same time as it argued for the rightful placePost-Beur of the French-born descendants of these colonial veterans in France, Hors-la-loi proved far more controversial. At the film’s premier in Cannes in May 2010, a group of protestors including veterans of the Algerian war, supporters of the far-right and harkis (Algerians who fought for the French in the war for independence) gathered on the Croisette to oppose what they saw as Hors-la-loi’s historical distortion of colonial history. Pressure was put on the organisers of the festival as well as French distributors and exhibitors to boycott the film that was attacked as ‘anti-French’ by Lionel Luca, a member of the centre-right UMP party (Jaffar 2010: 38). -

EMTEL); Basis of Requirements for Communication of Individuals with Authorities/Organizations in Case of Distress (Emergency Call Handling)

ETSI TR 102 180 V1.4.1 (2014-03) Technical Report Emergency Communications (EMTEL); Basis of requirements for communication of individuals with authorities/organizations in case of distress (Emergency call handling) 2 ETSI TR 102 180 V1.4.1 (2014-03) Reference RTR/EMTEL-00030 Keywords accessibility, emergency ETSI 650 Route des Lucioles F-06921 Sophia Antipolis Cedex - FRANCE Tel.: +33 4 92 94 42 00 Fax: +33 4 93 65 47 16 Siret N° 348 623 562 00017 - NAF 742 C Association à but non lucratif enregistrée à la Sous-Préfecture de Grasse (06) N° 7803/88 Important notice The present document can be downloaded from: http://www.etsi.org The present document may be made available in electronic versions and/or in print. The content of any electronic and/or print versions of the present document shall not be modified without the prior written authorization of ETSI. In case of any existing or perceived difference in contents between such versions and/or in print, the only prevailing document is the print of the Portable Document Format (PDF) version kept on a specific network drive within ETSI Secretariat. Users of the present document should be aware that the document may be subject to revision or change of status. Information on the current status of this and other ETSI documents is available at http://portal.etsi.org/tb/status/status.asp If you find errors in the present document, please send your comment to one of the following services: http://portal.etsi.org/chaircor/ETSI_support.asp Copyright Notification No part may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and microfilm except as authorized by written permission of ETSI. -

Generational Differences Between North African Francophone Literatures: the New Stories of Immigrants in France

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU Undergraduate Honors Capstone Projects Honors Program 5-2009 Generational Differences Between North African Francophone Literatures: The New Stories of Immigrants in France Christen M. Allen Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/honors Part of the French and Francophone Literature Commons, and the Other French and Francophone Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Allen, Christen M., "Generational Differences Between North African Francophone Literatures: The New Stories of Immigrants in France" (2009). Undergraduate Honors Capstone Projects. 6. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/honors/6 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors Program at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Capstone Projects by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GENERATIONAL DIFFERENCES BETWEEN BEUR AND NORTH AFRICAN FRANCOPHONE LITERATURES: THE NEW STORIES OF IMMIGRANTS IN FRANCE by Christen Marie Allen Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of HONORS IN UNIVERSITY STUDIES WITH DEPARTMENTAL HONORS in French in the Department of Languages, Philosophy and Speech Communication Approved: Committee Member Committee Member Dr. Christa Jones Dr. John Lackstrom Departmental Honors/Thesis Advisor Director of Honors Program Dr. Sarah Gordon Dr. Christie Fox UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY Logan, UT Spring 2009 Christen Allen Honors Thesis 2009 Generational Differences Between Beur and North African Francophone Literatures: The New Stories of Immigrants in France Abstract This study seeks to establish the generational difference between Beur and Francophone literatures using Kiffe Kiffe Demain by Faïza Guène contrasted with Le Siècle des Sauterelles by Malika Mokeddem. -

Outcomes of the Consultation Held on the Transition from Ipv4 To

ICT AUTHORITY Outcomes of the Consultation held on the Transition from IPv4 to IPv6 in Mauritius and the Recommendations thereon _________________________ _________________________ July 2011 Table of Contents Page 1. Executive Summary 3 2. Public Consultation Paper on Issues Pertaining to Transition from IPv4 to IPv6 6 in Mauritius 3. Compiled responses to technical questionnaire sent to Mauritian ISPs 20 4. Questionnaire sent to all ISPs in March 2011 24 5. Compilation of stakeholders’ comments 27 6. List of Abbreviations 42 ‐2‐ 1. Executive Summary The Internet is in transition. All the IPv4 addresses have already been allocated by IANA to the Regional Internet Registries; the Internet is in the progress of migrating to the new IPv6 address space. The exhaustion of IPv4 addresses and the transition to IPv6 could result in significant, but not insurmountable, problems for Internet services. In the short term, to allow the network to continue to grow, engineers have developed a series of kludges. These kludges include more efficient use of the IPv4 address resource, conservation, and the sharing of IPv4 addresses through the use of Network Address Translation (NAT). While these provide partial mitigation for IPv4 exhaustion they are not a long-term solution, they increase network costs, and merely postpone some of the consequences of address exhaustion without solving the underlying problem. The short term solutions are nevertheless necessary because there is not enough time to completely migrate the entire public Internet to "native IPv6" where end users can communicate entirely via IPv6. Network protocol transitions require significant work and investment, and with the exhaustion of IPv4 addresses looming, there is insufficient time to complete the full IPv6 transition. -

1 MUSLIM YOUTH IDENTITIES AMONG BEUR: an ANALYSIS of NORTH AFRICAN IMMIGRANTS and SELF-PERCEPTIONS in FRANCE by Lynette M. Mille

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by D-Scholarship@Pitt MUSLIM YOUTH IDENTITIES AMONG BEUR: AN ANALYSIS OF NORTH AFRICAN IMMIGRANTS AND SELF-PERCEPTIONS IN FRANCE by Lynette M. Miller Submitted to the Faculty of The College of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Philosophy in International and Area Studies University of Pittsburgh University Honors College 2010 1 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH UNIVERSITY HONORS COLLEGE This thesis was presented by Lynette M. Miller It was defended on April 2, 2010 and approved by Roberta Hatcher, Assistant Professor, French and Italian Languages and Literature Linda Winkler, Professor, Anthropology Philip Watts, Associate Professor, Department of French and Romance Philology at Columbia University Thesis Advisor: Mohammed Bamyeh, Associate Professor, Department of Sociology 2 Copyright © by Lynette M. Miller 2010 3 MUSLIM YOUTH IDENTITIES AMONG BEUR: AN ANALYSIS OF NORTH AFRICAN IMMIGRANTS AND SELF-PERCEPTIONS IN FRANCE Lynette M. Miller, BPhil University of Pittsburgh 2010 This paper explores the identities of Beur youth, both in terms of ethnic French perceptions of this group, as well as the Beur perspective of their individual and collective cultural identities. “Beur” refers to second and third generation immigrant youth in France of North African origins, and has become a nominator for an ethnic and cultural minority group in France. This minority group has spurred the development of activist groups, a unique sub-genre of hip-hop music, a slang dialect of French, and an entire French sub-culture. Noting this growing presence and influence of Beur culture in France, I posit the question: What roles do integration and inclusion in society play in Beur youth‟s development of individual identity and larger group identity, particularly in France? I examine this question through an exploratory qualitative research study to understand how Arab-Muslim immigrant youth, i.e. -

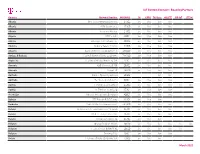

Network List Addendum

Network List Addendum IN-SITU PROVIDED SIM CELLULAR NETWORK COVERAGE COUNTRY NETWORK 2G 3G LTE-M NB-IOT COUNTRY NETWORK 2G 3G LTE-M NB-IOT (VULINK, (TUBE, (VULINK) (VULINK) TUBE, WEBCOMM) (VULINK, (TUBE, (VULINK) (VULINK) WEBCOMM) TUBE, WEBCOMM) WEBCOMM) Benin Moov X X Afghanistan TDCA (Roshan) X X Bermuda ONE X X Afghanistan MTN X X Bolivia Viva X X Afghanistan Etisalat X X Bolivia Tigo X X Albania Vodafone X X X Bonaire / Sint Eustatius / Saba Albania Eagle Mobile X X / Curacao / Saint Digicel X X Algeria ATM Mobilis X X X Martin (French part) Algeria Ooredoo X X Bonaire / Sint Mobiland Andorra X X Eustatius / Saba (Andorra) / Curacao / Saint TelCell SX X Angola Unitel X X Martin (French part) Anguilla FLOW X X Bosnia and BH Mobile X X Anguilla Digicel X Herzegovina Antigua and Bosnia and FLOW X X HT-ERONET X X Barbuda Herzegovina Antigua and Bosnia and Digicel X mtel X Barbuda Herzegovina Argentina Claro X X Botswana MTN X X Argentina Personal X X Botswana Orange X X Argentina Movistar X X Brazil TIM X X Armenia Beeline X X Brazil Vivo X X X X Armenia Ucom X X Brazil Claro X X X Aruba Digicel X X British Virgin FLOW X X Islands Australia Optus X CCT - Carribean Australia Telstra X X British Virgin Cellular X X Islands Australia Vodafone X X Telephone Austria A1 X X Brunei UNN X X Darussalam Austria T-Mobile X X X Bulgaria A1 X X X X Austria H3G X X Bulgaria Telenor X X Azerbaijan Azercell X X Bulgaria Vivacom X X Azerbaijan Bakcell X X Burkina Faso Orange X X Bahamas BTC X X Burundi Smart Mobile X X Bahamas Aliv X Cabo Verde CVMOVEL -

Tying of Broadband Internet Access and Pay-TV

Public Document INV 009 - Tying of Broadband Internet Access and pay-TV Report of the Executive Director 03/09/2012 © Competition Commission of Mauritius 2012 INV 009 – Tying of Broadband Internet Access and pay-TV 2 Table of Contents List of Abbreviations..........................................................................................................................................3 List of Tables and Figures .................................................................................................................................4 List of Annexes....................................................................................................................................................6 1. Summary ...............................................................................................................................................................7 2. Background...........................................................................................................................................................9 3. Legal Background..............................................................................................................................................17 4. Broadband Internet Access............................................................................................................................28 5. Pay-TV .................................................................................................................................................................32 6. Market -

Phone and Broadband Availability by Signing the Sales Order Summary

EMTEL LTD MC VISION LTD c/o MC VISION LTD Leclézio Street, Curepipe, Mauritius (230)6021818 Leclézio Street, Curepipe, Mauritius (230)6021818 Business ReGistration No : C06006174 VAT ReGistration No : VAT20064557 Business ReGistration No : C06018639 VAT ReGistration No : VAT20168416 Summary of terms and conditions: Pay TV Services Phone and Broadband Availability Once your application is accepted, your CanalBox subscription Gives access in diGital or By siGning the Sales Order Summary form you acknowledge that Emtel’s Double Play otherwise to the MC Vision’s Programmes, with or without a digital satellite decoder to Services may be subject to the availability of adequate broadband internet connection. receive those ProGrammes via the Eutelsat W3C satellite system or any other system In the event that the Double Play service cannot be installed, you may choose to which may replace it, or throuGh such other systems as may be used from time to time subscribe to MC Vision’s Pay TV offer only. In such a case, the monthly subscription fees by MC Vision Ltd for Pay TV only shall be applicable and the terms and conditions for Emtel’s Double Play Services shall not apply. Pay TV Services Equipment Your Broadband Allowance In case of loss, damaGe, theft, or tamperinG of any Equipment at your premises, the Your CanalBox subscription entitles you to an Unlimited Monthly Data Allowance. charges applicable are listed in MC Vision’s conditions of subscription annexed. All HiGh Speed Unlimited Broadband Internet Offers are governed by a Fair UsaGe Policy, which can be found on www.canalplus-maurice.com and www.emtel.com PLAY Service Equipment Broadband Speed In case of loss, damaGe, theft, or tamperinG of any Equipment at your The HiGh Speed Unlimited Broadband Internet Offer is a best effort service. -

Iot Custom Connect - Roaming Partners

IoT Custom Connect - Roaming Partners Country Column1 Network Provider Column2MCCMNCColumn10 Column32G Column4GPRS Column53G Data Column64G/LTE Column7NB-IoT LTE-M Albania One Telecommunications sh.a 27601 live live live live Albania ALBtelecom sh.a. 27603 live live live live Albania Vodafone Albania 27602 live live live live Algeria ATM Mobilis 60301 live live live live Algeria Wataniya Telecom Algerie 60303 live live live live Andorra Andorra Telecom S.A.U. 21303 live live live live Anguilla Cable and Wireless (Anguilla) Ltd 365840 live live live live Antigua & Barbuda Cable & Wireless (Antigua) Limited 344920 live live live live Argentina Telefónica Móviles Argentina S.A. 72207 live live live live Armenia VEON Armenia CJSC 28301 live live live live Armenia Ucom LLC 28310 live live live live Australia SingTel Optus Pty Limited 50502 live live Australia Telstra Corporation Ltd 50501 live live live live Austria T-Mobile Austria GmbH 23203 live live live live live live Austria A1 Telekom Austria AG 23201 live live live live Azerbaijan Bakcell Limited Liable Company 40002 live live live live Bahrain STC Bahrain B.S.C Closed 42604 live live live Barbados Cable & Wireless Barbados Ltd. 342600 live live live live Belarus Belarusian Telecommunications Network 25704 live live live live Belarus Mobile TeleSystems JLLC 25702 live live live live Belarus Unitary Enterprise A1 25701 live live live Belgium Orange Belgium NV/SA 20610 live live live live live live Belgium Telenet Group BVBA/SPRL 20620 live live live live live Belgium Proximus PLC 20601 live live live live Bolivia Telefonica Celular De Bolivia S.A. 73603 live live live March 2021 IoT Custom Connect - Roaming Partners Country Column1 Network Provider Column2MCCMNCColumn10 Column32G Column4GPRS Column53G Data Column64G/LTE Column7NB-IoT LTE-M Bosnia and Herzegovina PUBLIC ENTERPRISE CROATIAN TELECOM Ltd.