In Objectivist Epistemology, Induction and Concept-Formation Are Closely Related

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Original Lists of Persons of Quality, Emigrants, Religious Exiles, Political

Cornell University Library The original of tiiis book is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924096785278 In compliance with current copyright law, Cornell University Library produced this replacement volume on paper that meets the ANSI Standard Z39.48-1992 to replace the irreparably deteriorated original. 2003 H^^r-h- CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY BOUGHT WITH THE INCOME OF THE SAGE ENDOWMENT FUND GIVEN IN 1891 BY HENRY WILLIAMS SAGE : ; rigmal ^ist0 OF PERSONS OF QUALITY; EMIGRANTS ; RELIGIOUS EXILES ; POLITICAL REBELS SERVING MEN SOLD FOR A TERM OF YEARS ; APPRENTICES CHILDREN STOLEN; MAIDENS PRESSED; AND OTHERS WHO WENT FROM GREAT BRITAIN TO THE AMERICAN PLANTATIONS 1600- I 700. WITH THEIR AGES, THE LOCALITIES WHERE THEY FORMERLY LIVED IN THE MOTHER COUNTRY, THE NAMES OF THE SHIPS IN WHICH THEY EMBARKED, AND OTHER INTERESTING PARTICULARS. FROM MSS. PRESERVED IN THE STATE PAPER DEPARTMENT OF HER MAJESTY'S PUBLIC RECORD OFFICE, ENGLAND. EDITED BY JOHN CAMDEN HOTTEN. L n D n CHATTO AND WINDUS, PUBLISHERS. 1874, THE ORIGINAL LISTS. 1o ihi ^zmhcxs of the GENEALOGICAL AND HISTORICAL SOCIETIES OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, THIS COLLECTION OF THE NAMES OF THE EMIGRANT ANCESTORS OF MANY THOUSANDS OF AMERICAN FAMILIES, IS RESPECTFULLY DEDICATED PY THE EDITOR, JOHN CAMDEN HOTTEN. CONTENTS. Register of the Names of all the Passengers from London during One Whole Year, ending Christmas, 1635 33, HS 1 the Ship Bonavatture via CONTENTS. In the Ship Defence.. E. Bostocke, Master 89, 91, 98, 99, 100, loi, 105, lo6 Blessing . -

History of Physics Group Newsletter No 21 January 2007

History of Physics Group Newsletter No 21 January 2007 Cover picture: Ludwig Boltzmann’s ‘Bicykel’ – a piece of apparatus designed by Boltzmann to demonstrate the effect of one electric circuit on another. This, and the picture of Boltzmann on page 27, are both reproduced by kind permission of Dr Wolfgang Kerber of the Österreichische Zentralbibliothek für Physik, Vienna. Contents Editorial 2 Group meetings AGM Report 3 AGM Lecture programme: ‘Life with Bragg’ by John Nye 6 ‘George Francis Fitzgerald (1851-1901) - Scientific Saint?’ by Denis Weaire 9 ‘Benjamin Franklin (1706-1790) - a brief biography by Peter Ford 15 Reports Oxford visit 24 EPS History of physics group meeting, Graz, Austria 27 European Society for the History of Science - 2nd International conference 30 Sir Joseph Rotblat conference, Liverpool 35 Features: ‘Did Einstein visit Bratislava or not?’ by Juraj Sebesta 39 ‘Wadham College, Oxford and the Experimental Tradition’ by Allan Chapman 44 Book reviews JD Bernal – The Sage of Science 54 Harwell – The Enigma Revealed 59 Web report 62 News 64 Next Group meeting 65 Committee and contacts 68 2 Editorial Browsing through a copy of the group’s ‘aims and objectives’, I notice that part of its aims are ‘to secure the written, oral and instrumental record of British physics and to foster a greater awareness concerning the history of physics among physicists’ and I think that over the years much has been achieved by the group in tackling this not inconsiderable challenge. One must remember, however, that the situation at the time this was written was very different from now. -

The Latitudinarian Influence on Early English Liberalism Amanda Oh Southern Methodist University, [email protected]

Southern Methodist University SMU Scholar The Larrie and Bobbi Weil Undergraduate Research Central University Libraries Award Documents 2019 The Latitudinarian Influence on Early English Liberalism Amanda Oh Southern Methodist University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.smu.edu/weil_ura Part of the European History Commons, History of Religion Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Oh, Amanda, "The Latitudinarian Influence on Early English Liberalism" (2019). The Larrie and Bobbi Weil Undergraduate Research Award Documents. 10. https://scholar.smu.edu/weil_ura/10 This document is brought to you for free and open access by the Central University Libraries at SMU Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Larrie and Bobbi Weil Undergraduate Research Award Documents by an authorized administrator of SMU Scholar. For more information, please visit http://digitalrepository.smu.edu. The Latitudinarian Influence on Early English Liberalism Amanda Oh Professor Wellman HIST 4300: Junior Seminar 30 April 2018 Part I: Introduction The end of the seventeenth century in England saw the flowering of liberal ideals that turned on new beliefs about the individual, government, and religion. At that time the relationship between these cornerstones of society fundamentally shifted. The result was the preeminence of the individual over government and religion, whereas most of Western history since antiquity had seen the manipulation of the individual by the latter two institutions. Liberalism built on the idea that both religion and government were tied to the individual. Respect for the individual entailed respect for religious diversity and governing authority came from the assent of the individual. -

Obedience Robins of Accomack: 17Th-Century

OBEDIENCE ROBINS OF ACCOMACK: 17TH-CENTURY STRATEGIES FOR SUCCESS A Thesis MARY CA~ WILHEIT Submitted to the Once of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS December 1997 Major Subject: History OBEDIENCE ROBINS OF ACCOMACK: 17TH-CENTURY STRATEGIES FOR SUCCESS A Thesis MARY CA~ WILHEIT Submitted to Texas AyrM University in partial tulfillment of thc requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Approved as to style and content by. John L. Canup Walter L. Buenger ( hair of Committee) (Member) Dennis A. Berthold Julia Kirk ckvvelder (Member) (Head ol Dcpa nt) December 1997 Major Subject: History ABSTRACT Obedience Robins of Accomack: 17th-Century Strategies for Success. (December 1997) Mary Catherine Wilheit, A. B., Wilson College Chair of Advisory Committee: Dr. John L. Canup Obedience Robins emigrated to Virginia in the 1620s in search of the land and status his elder brother gained by inheritance. This thesis establishes motivations for immigration and methods by which one English emigr6 achieved success in Virginia. The 1582 will of Richard Robins established a pattern of primogeniture for successive generations of his Northamptonshire family. Muster lists, wills, parish registers and a 1591 manor survey record increasing prosperity and associated expectations. Robinses were among those "better sorts" who paid taxes, provided armour, held local office, educated their children, and protcstcd against perceived government injustice. In Virginia. Richard Robins*s great grandson parlayed his assets into land, office and status. The extent of his education and financial resources was probably limited, but good health, timing. -

Puritans and the Royal Society

Faith and Thought A Journal devoted to the study of the inter-relation of the Christian revelation and modern research Vol. 92 Number 2 Winter 1961 C. E. A. TURNER, M.Sc., PH.D. Puritans and the Royal Society THE official programme of the recent tercentenary celebrations of the founding of the Royal Society included a single religious service. This was held at 10.30 a.m. at St Paul's Cathedral when the Dean, the Very Rev. W. R. Matthews, D.D., D.LITT., preached a sermon related to the building's architect, Sir Christopher Wren. Otherwise there seems to be little reference to the religious background of the Society's pioneers and a noticeable omission of appreciation of the considerable Puritan participation in its institution. The events connected with the Royal Society's foundation range over the period 1645 to 1663, but there were also earlier influences. One of these was Sir Francis Bacon, Lord Verulam, 1561-1626. Douglas McKie, Professor of the History and Philosophy of Science, University College, London, in The Times Special Number, 19 July 1960, states that Bacon's suggested academy called Solomon's House described in New Atlantis (1627) was too often assumed to be influential in the founding of the Royal Society, much in the same way as Bacon's method of induction, expounded in his Novum Organum of 1620, has been erroneously regarded as a factor in the rise of modern science. But this may be disputed, for Bacon enjoyed considerable prestige as a learned man and his works were widely read. -

John Wilkins's Analytical Language

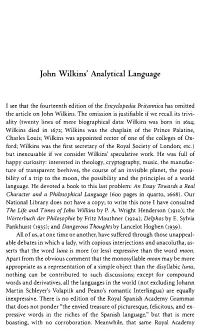

John Wilkins' Analytical Language I see that the fo urteenth edition of the Encyclopedia Britannica has omitted the article on John Wilkins. The omission is justifiable if we recall its trivi ality (twenty lines of mere biographical data: Wilkins was born in 1614; Wilkins died in 1672; Wilkins was the chaplain of the Prince Palatine, Charles Louis; Wilkins was appointed rector of one of the colleges of Ox fo rd; Wilkins was the first secretary of the Royal Society of London; etc.) but inexcusable if we consider Wilkins' speculative work. He was full of happy curiosity: interested in theology, cryptography, music, the manufac ture of transparent beehives, the course of an invisible planet, the possi bility of a trip to the moon, the possibility and the principles of a world language. He devoted a book to this last problem: An Essay To wards a Real Character and a Philosophical Language (6oo pages in quarto, 1668). Our National Library does not have a copy; to write this note I have consulted The Life and Times of john Wilkins by P. A. Wright Henderson (1910); the Worterbuch der Philosophie by Fritz Mauthner (1924); Delphos by E. Sylvia Pankhurst (1935); and Dangerous Thoughts by Lancelot Hogben (1939). All ofus, at one time or another, have suffered through those unappeal able debates in which a lady, with copious interjections and anacolutha, as serts that the word luna is more (or less) expressive than the word moon. Apart from the obvious comment that the monosyllable moon may be more appropriate as a representation of a simple object than the disyllabic luna, nothing can be contributed to such discussions; except for compound words and derivatives, all the languages in the world (not excluding Johann Martin Schleyer's Volapiik and Peano's romantic Interlingua) are equally inexpressive. -

The Analytical Language of John Wilkins

The Analytical Language of John Wilkins )€_� I see that the fourteenth edition of the Encyclopaedia Brilan � nica has omitted the article about John Wilkins. The omission is justified if we remember how trivial it was (twenty lines of bio graphical data: Wilkins was born in 1614, Wilkins died in 1672, Wilkins was the chaplain of the Prince Palatine, Charles Louis; Wilkins was appointed recto� of one of the colleges of Oxford; Wil kins was the first secretary of the Royal Society of London, etc. ) ; but not if we consider the speculative work of Wilkins. He abounded in happy curiosities: he was interested in theology, cryptography, music, the manufacture of transparent beehives, the course of an invisible planet, the possibility of a trip to the moon, the possibility and the principles of a world language. It was to this last problem that he dedicated the book An Essay towards a Real Character and a Philosophical Language ( 600 pages in quarto, 1668). Our National Library does not have a copy of that book. To write this article I have consulted The Life and Times of fohn Wilkins by P. A. Wright Henderson (1910), the Woerterbuch der Philosophie by Fritz Mauthner (1924), Delphos by E. Sylvia Pankhurst (1935), and Dangerous Thoughts by Lancelot Hogben (1939). At one time or another, we have all suffered through those unap pealable debates in which a lady, with copious interjections and 101 anacolutha, swears that the word luna is more (or less) expressive than the word moon. Apart from the sell-evident observation that the monosyllable moon may be more appropriate to represent a very simple object than the disyllabic word luna, nothing can be contrib uted to such discussions. -

Kaleidoscopic Natural Theology

Kaleidoscopic Natural Theology The Dynamics of Natural Theological Discourse in Seventeenth and Early Eighteenth-Century England Larissa Kate Johnson A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of New South Wales, Australia 2009 ORIGINALITY STATEMENT I hereby declare that this submission is my own work and to the best of my knowledge it contains no materials previously published or written by another person, or substantial proportions of material which have been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma at UNSW or any other educational institution, except where due acknowledgement is made in the thesis. Any contribution made to the research by others, with whom I have worked at UNSW or elsewhere, is explicitly acknowledged in the thesis. I also declare that the intellectual content of this thesis is the product of my own work, except to the extent that assistance from others in the project's design and conception or in style, presentation and linguistic expression is acknowledged. Signed ................................................................. Date .................................................................. i COPYRIGHT STATEMENT I hereby grant the University of New South Wales or its agents the right to archive and to make available my thesis or dissertation in whole or part in the University libraries in all forms of media, now or here after known, subject to the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. I retain all proprietary rights, such as patent rights. I also retain the right to use in future works (such as articles or books) all or part of this thesis or dissertation. I also authorise University Microfilms to use the 350 word abstract of my thesis in Dissertation Abstract International (this is applicable to doctoral theses only). -

THE ANALYTICAL LANGUAGE of JOHN WILKINS Present

THE ANALYTICAL LANGUAGE OF JOHN WILKINS Present Past By Jorge Luis Borges Subjects Translated from the Spanish 'El idioma analítico de John Wilkins' by Lilia Graciela Vázquez; edited by Jan Frederik Solem with Projects assistance from Bjørn Are Davidsen and Rolf Andersen. A Misc translation by Ruth L. C. Simms can be found in Jorge Luis Borges, 'Other inquisitions 1937-1952' (University of Texas Press, 1993) I have noticed that the 14th edition of Encyclopedia Britannica does not include the article on John Wilkins. This omission can be considered justified if we remember how trivial this article was (20 lines of purely biographical data: Wilkins was born in 1614, Wilkins died in 1672, Wilkins was chaplain of Charles Louis, Elector Palatine; Wilkins was principal of one of Oxford's colleges, Wilkins was the first secretary of the Royal Society of London, etc.); it is an error if we consider the speculative works of Wilkins. He was interested in several different topics: theology, cryptography, music, the building of transparent beehives, the orbit of an invisible planet, the possibility of a trip to the moon, the possibility and principles of an universal language. To this latter problem he dedicated the book 'An Essay Towards a Real Character and a Philosophical Language' (600 pages in large quarto, 1668). There are no copies of this book in our National Library, I have consulted, to write the present article, 'The Life and Times of John Wilkins' (1910), by P. A. Wright Henderson; the 'Wörterbuch der Philosophie' (1935), by Fritz Mauthner; 'Delphos' (1935), by E. Sylvia Pankhurst; 'Dangerous Thoughts' (1939), by Lancelot Hogben. -

Exploring Ordained Vocation

Exploring Ordained Vocation Thank you for taking the time to consider this pack. In it you will find out more about the people involved in the discernment process, discover what is involved in helping you find the right path on this important journey and resources to help you find out more for yourself. We are all praying for you as you take your journey further. The Vocations Team 1. Understanding Discernment to Ordained Ministry Discernment is a journey of discovery to help you grow your God-given gifts. At some point in the journey, a decision is taken as to whether your gifts are the right ones for ordained ministry. Time spent discerning your vocation is a time of personal growth. You will be increasing in self-awareness, developing a disciplined prayer-life, and building your knowledge. Father, I abandon myself into your hands. Do with me whatever you will. Whatever you may do I thank you. I am ready for all, I accept all. Let only your will be done in me and all your creatures. I wish no more than this, O Lord. Into your hands I commend my soul. I offer it to you with all the love of my heart. For I love you Lord and so need to give myself, surrender myself into your hands without reserve and with boundless confidence for you are my Father. Amen Foucauld (1858–1916) Confidentiality People exploring ordination are advised that whatever emerges as part of the process of discernment is liable to be shared with those who are part of the decision-making process within the Diocese, and with the Advisors should the candidate be sponsored for a Selection Conference. -

Calloway Curriculum Vitae February 2017

Curriculum Vitae Katherine Elizabeth Calloway Department of English Baylor University One Bear Place #97404 Waco, TX 76798-7404 [email protected] Education 2010 PhD, English Literature, University of British Columbia 2005 Master of Arts, English Literature, Baylor University 2003 Bachelor of Arts, Magna Cum Laude, Baylor University, University Scholars Professional Appointments 2016-2018 Postdoctoral Fellow in English, Baylor University, Waco, TX 2014-2016 Visiting Assistant Professor, Westmont College, Santa Barbara, CA 2011-2013 Lilly Postdoctoral Fellow in the Humanities, Valparaiso University, Valparaiso, IN 2010-2011 Lecturer, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC Publications Book Natural Theology in the Scientific Revolution: God’s Scientists. London, UK: Pickering & Chatto, 2014. 205 pp. [Reviews: P. Jordan in Journal of Religious History; R.J.W. Mills in Journal of Ecclesiastical History] “Calloway succeeds admirably in demonstrating the diversity of early modern English approaches to natural theology . For those keen to discern natural theology’s contribution to modernity, Calloway’s book has much to offer.” P. Jordan, Journal of Religious History “Calloway’s analysis is careful, biographically detailed and often witty. The book can be read profitably by intellectual historians of seventeenth-century English thought, and it can also serve as an introductory text for advanced postgraduates.” R.J.W. Mills, Journal of Ecclesiastical History Refereed Journal Articles “‘His Footstep Trace’: the Natural Theology of Paradise Lost.” Milton Studies 55 (2014): 53-85. “Milton’s Lucretian Anxiety Revisited.” Renaissance and Reformation 32.3 (2009): 79-97. “Wordsworth’s The Prelude as Autobiographical Epic” The Charles Lamb Bulletin 141 (2008): 13-19. “Beyond Parody: Satan as Aeneas in Paradise Lost.” Milton Quarterly 39.2 (2005): 82-92. -

A Culture of Habit: Habitual Dispositions in Late Early Modern English Intellectual Thought

A Culture of Habit: Habitual Dispositions in Late Early Modern English Intellectual Thought A dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the degree of PhD in History, by: Martin P. Walker, B.A., M.Sc. (Lancaster University, Utrecht University) Lancaster University, May (2019). 31404700 A Culture Of Habit Words: 80,325 To my Mother, For teaching me how to be a decent human being. & To Joe, A best friend who always gave me the best advice: “You’re not good enough for a PhD, Martin.” You are both never far from my mind. This is for you. ii 31404700 A Culture Of Habit Words: 80,325 Abstract This thesis examines the concept of ‘habit’ and notions of ‘habitual dispositions’ in late early modern English thought. It’s primary aim is to highlight the ways in which the process of acquiring habitual dispositions was an integral part of late Early Modern English intellectual life, which was founded upon the need to habituate the individual to internalise moral virtues and to govern their passions and actions so as to cultivate religious sociability, establish epistemological consensus, and maintain civil society. Chapter 1 presents a new reading of the concept of ‘right reason’ through a close examination of the works of Henry More and John Wilkins. Chapter 2 examines the notion of habitual dispositions in Restoration religion, focusing on how a group of loosely connected moderate divines attempted to fashion a religion that was founded on habitually acquired moral beliefs and dispositions. Chapter 3 then shifts the focus to the context of the new experimental philosophy, demonstrating how experimental philosophers such as Robert Boyle and Robert Hooke were preoccupied with cultivating good experimental habitual behaviour and dispositions.