Transport and Environment Committee

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lets Talk Issue 39.Indd

Let’s Talk about corstorphine CRAIGMOUNT HIGH SCHOOL PIPE BAND “MIKE LAIRD – CROSSING THE LINE SUMMER 2017 CORSTORPHINE COMMUNITY CHURCH A magazine produced by St Ninian’s Church, Corstorphine LETS TALK ABOUT” CORSTORPHINE 1ISSUE 39 Welcome to Corstorphine Churches Carrick Knowe Parish Church St Andrew’s Church St Ninian’s Church Church of Scotland Saughton Road North Church of Scotland Church of Scotland www.ckchurch.org.uk Clermiston View St John’s Road Main Sunday Service: 11am www.edinburghstandrewsclermiston.org.uk www.corstorphinestninians.org.uk July-August: 10.30am Main Sunday Service: 10.30am Main Sunday Service: 10.30am Evening Services as intimated Minister: Rev. Alistair Keil Evening Services as intimated Minister: Rev. Fiona Mathieson St Anne’s Church St Thomas’ Church Corstorphine Old Parish Church Church of Scotland Scottish Episcopal Church of Scotland Kirk Loan Kaimes Road Glasgow Road www.corstorphineoldparish.org.uk www.stannescorstorphine.org.uk www.saintthomas.org.uk Main Sunday Service: 10.30am Main Sunday Service: 11am Main Sunday Service: 10.30am Minister: Rev. Moira McDonald July-August 10.30am Rector: Rev. David McCarthy Minister: Rev. James Griggs Corstorphine Craigsbank Parish Church St Kentigern’s Roman Catholic Church of Scotland (One Church 2 centres) St John the Baptist Parkgrove Avenue www.craigsbankchurch.org.uk Roman Catholic www.stkentigernsedinburgh.co.uk At East Craigs Church Centre St Ninian’s Road Sunday Morning Mass: 10.15am (Bughtlin Market) www.stjohnthebaptist.rcstanded.org.uk Holy Days of Obligation: Main Sunday Service: 9.45am Saturday Mass: 6pm As announced Craigsbank Church Sunday Mass: 10am Weekday Mass 10am. (During Summer, (North of Glasgow Road) Holy Days of Obligation: Tuesday Mass is at 7pm) Main Sunday Service: 11.30am Vigil Mass at 7.30pm & 9.00am Parish Priest: Father James Tracey Minister: Rev. -

Report on Data to Inform the City of Edinburgh Licensing Board's Duty

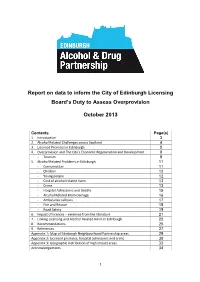

Report on data to inform the City of Edinburgh Licensing Board’s Duty to Assess Overprovision October 2013 Contents Page(s) 1. Introduction 3 2. Alcohol Related Challenges across Scotland 4 3. Licensed Premises in Edinburgh 5 4. Overprovision and The City’s Economic Regeneration and Development 8 - Tourism 9 5. Alcohol Related Problems in Edinburgh 11 - Consumption 11 - Children 12 - Young people 12 - Cost of alcohol related harm 13 - Crime 13 - Hospital Admissions and Deaths 15 - Alcohol Related Brain Damage 16 - Ambulance callouts 17 - Fire and Rescue 18 - Road Safety 19 6. Impact of licences – evidence from the literature 21 7. Linking Licensing and Alcohol Related Harm in Edinburgh 22 8. Recommendations 25 9. References 27 Appendix 1: Map of Edinburgh Neighbourhood Partnership areas 29 Appendix 2: Licensed premises, hospital admissions and crime 30 Appendix 3: Geographic distribution of high impact areas 33 Acknowledgements 34 1 Report prepared by: Hannah Carver, Research and Evaluation Officer, Edinburgh Alcohol and Drug partnership (ADP) Support Team on behalf of the Edinburgh ADP Overprovision Steering Group. 2 1. Introduction Licensing Boards have the power to identify areas of overprovision where it is deemed that the granting of further licensing would undermine the 5 five objectives enshrined in the Licensing (Scotland) Act 2005. These are: Preventing Crime and Disorder Securing Public Safety Preventing Public Nuisance Protecting and Improving Public Health Protecting Children from Harm In Edinburgh the Licensing Board has identified the Grassmarket, Cowgate and streets leading to it as a long established area of overprovision. In November 2011 Jim Sherval, Public Health Specialist in NHS Lothiani, completed an assessment of overprovision provision on behalf of the Board. -

(Maybury) General Medical Services Provision Edinburgh Integration Joint Board 24 August 2020

REPORT West Edinburgh (Maybury) General Medical Services Provision Edinburgh Integration Joint Board 24 August 2020 Executive Summary The purpose of this report is to provide the Edinburgh Integration Joint Board with the Initial Agreement for the Provision of General Medical Services in West Edinburgh (Maybury). The proposal seeks capital funding from NHS Lothian and the Initial Agreement has been prepared in line with the guidance contained in the Scottish Capital Investments Manual. Recommendations It is recommended that the Edinburgh Integration Joint Board 1. Agree the proposal to provide General Medical Services in West Edinburgh 2. Note that NHS Lothian invited Edinburgh Health and Social Care Partnership (EHSCP) to submit an Initial Agreement for this proposal following the conclusion of the 2020-21 Capital Prioritisation Process. 3. Approve the proposal and agree the presentation of the Initial Agreement to NHS Lothian’s Finance and Resources Committee. Directions Direction to City of ✓ Edinburgh Council, No direction required ✓ NHS Lothian or Issue a direction to City of Edinburgh Council both organisations Issue a direction to NHS Lothian Issue a direction to City of Edinburgh Council and NHS Lothian 1 Main Report 1. The population of Edinburgh has increased by some 65,000 people over the last 10 years and will continue to grow at a rate c5,000-6000 per annum, until at least 2026. This trend is expected to continue further in the next Local Development Plan known as City Plan 2030. 2. Greenfield space (site HSG19) (Initial Agreement appendix 2)adjacent to Maybury and between Turnhouse Road and the main rail link to Fife, has been released for housing development through the City of Edinburgh (CEC) Local Development Plan 2016 – 2026. -

Local Development Plan Action Programme January 2019

ACTION PROGRAMME � JANUARY 2019 The Local Development Plan sets out policies and proposals to guide development. Adopted 24 November 2016 The Action Programme sets out actions to deliver the Plan. The Report of Conformity explains how engagement informed the Plan. The Habitats Regulations Appraisal assesses the Plan’s impact on internationally important bird habitats. The Transport Appraisal identifies transport actions to support the Plan. The Education Appraisal identifies new and expanded schools to support the Plan. The Equalities & Rights Impact Assessment checks what impact the Plan will have on people. The Environmental Report assesses the impact of the Plan and explains the selection of new housing sites. ACTION PROGRAMME The Housing Land Study sets out the assumption on housing land JANUARY 2019 availability which inform the Local Development Plan. See the documents, supplementary guidance, and other information at: www.edinburgh.gov.uk/localdevelopmentplan www.edinburgh.gov.uk/supplementaryguidance Published in 2011 Published in 2013 Published in 2014 MAIN ISSUES REPORT OCTOBER 2011 Edinburgh Local Development Plan Action Programme January 2019 Contents Introduction 1. Education Actions 2. Transport Actions a. Strategic transport actions b. Transport Contribution Zones c. Site specific actions d. Rest of the urban area i. North East Locality ii. North West Locality 3. Greenspace Actions 4. Healthcare and Community Facilities 5. Utilities 6. City Centre and Town Centre Actions 7. LDP Policies and Supplementary Guidance 8. Completed actions at January 2019 Edinburgh Local Development Plan Action Programme January 2019 lever the best possible outcome for the city and to coordinate INTRODUCTION development proposals with the infrastructure and services needed to support them. -

Lothian NHS Board Waverley Gate 2-4 Waterloo Place Edinburgh EH1 3EG

Lothian NHS Board Waverley Gate 2-4 Waterloo Place Edinburgh EH1 3EG Telephone: 0131 536 9000 www.nhslothian.scot.nhs.uk www.nhslothian.scot.nhs.uk Date: 05/04/2019 Your Ref: Our Ref: 3431 Enquiries to : Richard Mutch Extension: 35687 Direct Line: 0131 465 5687 [email protected] Dear FREEDOM OF INFORMATION – GP CATCHMENT I write in response to your request for information in relation to GP catchment areas within Lothian. I have been provided with information to help answer your request by the NHS Lothian Primary Care Contract Team. Question: Can you please provide an updated version of the Lothians GP catchment areas list as found at https://www.nhslothian.scot.nhs.uk/YourRights/FOI/RequestAndResponseRegister/2012/320 0.pdf Answer: Practice Practice Name wef Practice Boundary No 70075 Braids Medical 27/09/18 On the northern boundary – the railway line running Practice through Morningside Station. On the west – Colinton 6 Camus Avenue Road where it crosses the railway continuing into Edinburgh EH10 Colinton Mains Drive to the Tesco Roundabout, then 6QT continuing south south-east across country to the Dreghorn Link to the City By-Pass. On the south – cuts across country from the Dreghorn Link to Swanston Golf Course and around the south perimeter of Swanston Golf Course and Swanston village cutting across country in a south easterly direction to meet the Lothian Burn at Hillend Car Park and along the access road until it meets the Bigger Road (A702). Continuing south on the A702 until the triple junction where the A702 meets the A703 and Old Pentland Road, across country in a straight line, crossing the Edinburgh City Bypass (A720) passing the east end of Winton Loan and north by Morton House to Frogston Road West. -

P7 Leavers Yearbook

2020 Clermiston Primary P 7 L E A V E R S Y E A R B O O K TABLE OF CONTENTS 3 Message from Mr McIntyre 8 Pupil Profiles Message from Mrs Hamilton- 5 Irvine and Miss Passaretti 67 Messages from friends 6 Primary 1 Photo Gallery 69 Teacher Signatures A MESSAGE FROM MR MCINTYRE Dear Primary 7 Every year I write a letter to P7s to wish them a fond farewell as they leave Clermiston and get ready to start their time at High School. As you can imagine, this year has made it extra-difficult to know what to say. I thought about it for ages and ages and then I wrote… Ooft! But I didn’t think that was quite good enough and so I up-levelled it a bit… Ooft! What a year that was eh? But then I thought, maybe that wasn’t good enough either. I remembered that Primary 7 is only one year of your Primary School life. Some of you have been with us for 9 years if you include nursery. Lots of you have been with us from Primary 1 and lots of you have joined us on your own journey through Primary School. So then I wrote this… Ooft! What a year that was eh? You have all been through a unique Primary 7 year that no-one could have predicted. I feel for you all that you didn’t get to have the Primary 7 Summer Term that you deserved and that you would have enjoyed so much. -

Applicant Data

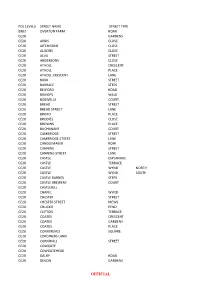

POL LEVEL5 STREET NAME STREET TYPE BX02 OVERTON FARM ROAD CE20 GARDENS CE20 AIRDS CLOSE CE20 AITCHISONS CLOSE CE20 ALISONS CLOSE CE20 ALVA STREET CE20 ANDERSONS CLOSE CE20 ATHOLL CRESCENT CE20 ATHOLL PLACE CE20 ATHOLL CRESCENT LANE CE20 BANK STREET CE20 BARRACE STEPS CE20 BELFORD ROAD CE20 BISHOPS WALK CE20 BOSWELLS COURT CE20 BREAD STREET CE20 BREAD STREET LANE CE20 BRISTO PLACE CE20 BRODIES CLOSE CE20 BROWNS PLACE CE20 BUCHANANS COURT CE20 CAMBRIDGE STREET CE20 CAMBRIDGE STREET LANE CE20 CANDLEMAKER ROW CE20 CANNING STREET CE20 CANNING STREET LANE CE20 CASTLE ESPLANADE CE20 CASTLE TERRACE CE20 CASTLE WYND NORTH CE20 CASTLE WYND SOUTH CE20 CASTLE BARNES STEPS CE20 CASTLE BREWERY COURT CE20 CASTLEHILL CE20 CHAPEL WYND CE20 CHESTER STREET CE20 CHESTER STREET MEWS CE20 CHUCKIE PEND CE20 CLIFTON TERRACE CE20 COATES CRESCENT CE20 COATES GARDENS CE20 COATES PLACE CE20 CONFERENCE SQUARE CE20 CORDINERS LAND CE20 CORNWALL STREET CE20 COWGATE CE20 COWGATEHEAD CE20 DALRY ROAD CE20 DEVON GARDENS OFFICIAL CE20 DEVON PLACE CE20 DEWAR PLACE CE20 DEWAR PLACE LANE CE20 DOUGLAS CRESCENT CE20 DOUGLAS GARDENS CE20 DOUGLAS GARDENS MEWS CE20 DRUMSHEUGH GARDENS CE20 DRUMSHEUGH PLACE CE20 DUNBAR STREET CE20 DUNLOPS COURT CE20 EARL GREY STREET CE20 EAST FOUNTAINBRIDGE CE20 EDMONSTONES CLOSE CE20 EGLINTON CRESCENT CE20 FESTIVAL SQUARE CE20 FORREST HILL CE20 FORREST ROAD CE20 FOUNTAINBRIDGE CE20 GEORGE IV BRIDGE CE20 GILMOURS CLOSE CE20 GLADSTONES LAND CE20 GLENCAIRN CRESCENT CE20 GRANNYS GREEN STEPS CE20 GRASSMARKET CE20 GREYFRIARS PLACE CE20 GRINDLAY STREET CE20 -

CIMT 17/07/20 – Spaces for People Project Approval

CIMT 17/07/20 – Spaces for People Project Approval Notification sent to all ward councillors, transport spokespeople, emergency services, Living Streets, Spokes, RNIB, Edinburgh Access Panel and relevant Community Councils on 7 July 2020. Recipients were given five days to respond with comments. The measures would be implemented under emergency delegated decision-making powers using a Temporary Traffic Regulation Order. Given the urgent nature of these works, normal expectations about community consultations cannot be fulfilled. Project Proposal Location Justification Recommendation Wester Hailes Provide protected cycling infrastructure on a key major route to Progress with scheme as part of Road important local destinations such as a shopping centre, the rail station, overall emergency measures to re- Education centre and cycling routes along the canal. This will enable designate key parts of the road communities in this area of the city to travel safely by bike as lockdown network to help pedestrians and eases. cyclists travel safely while meeting physical distancing requirements. Feedback Comment from Comment Response Cllr Miller I don’t know this road quite well enough to provide Noted. comments in detail, but I am supportive of the concept and look forward to this progressing to delivery Cllr Webber As the local ward Cllr I cannot support the There is a coherent rationale behind these disproportionate proposal and can only seek to plead proposals. They have been evolved based on with officers that this is reconsidered quickly. There previous local consultation, via the West Edinburgh are improvements needed and I am happy to discuss Link (WEL) which showed strong support for these (again) with the relevant officers to achieve the improving cycle provision along Wester Hailes schemes objectives but as they are presented today Road. -

Developer Contributions and Infrastructure Delivery August 2018 1

SUPPLEMENTARY GUIDANCE DEVELOPER CONTRIBUTIONS & INFRASTRUCTURE DELIVERY Finalised version August 2018 Contents 1. Introduction ...............................................................................................................................................................................1 What does this guidance do? 1 Use of this guidance 1 Relevant policies 1 2. Delivering the Edinburgh Local Development Plan .........................................................................................................................2 Infrastructure requirements associated with new development 2 Contribution Zones 3 2a. Education Infrastructure 4 2b. Transport Infrastructure 6 2c. Greenspace 9 2d. Public Realm 10 2e. Primary healthcare 11 3. Viability and Funding Mechanisms .............................................................................................................................................. 12 4. Legal Agreements and use of monies ........................................................................................................................................... 13 5. Audit and Review ...................................................................................................................................................................... 14 Annex 1 Education Infrastructure ............................................................................................................................................ 15 Annex 2 Transport Infrastructure ............................................................................................................................................ -

Index of Edinburgh Street Names and Districts

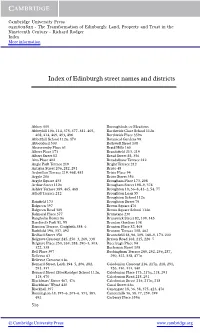

Cambridge University Press 0521602823 - The Transformation of Edinburgh: Land, Property and Trust in the Nineteenth Century - Richard Rodger Index More information Index of Edinburgh street names and districts Abbey 445 Boroughloch see Meadows Abbeyhill 106, 114, 375, 377, 381, 405, Borthwick Close School 112n 408, 414, 469, 493, 496 Borthwick Place 359n Abbeyhill School 112n, 470 Botanical Gardens 98 Abbotsford 500 Bothwell Street 108 Abercromby Place 61 Braid Hills 165 Albert Place 173 Brandsfield 213, 219 Albert Street 82 Bread Street 88, 356 Alva Place 402 Breadalbane Terrace 212 Angle Park Terrace 219 Bright Terrace 212 Antigua Street 206, 282, 291 Bristo 48 Ardmillan Terrace 219, 468, 481 Bristo Place 94 Argyle 206 Bristo Street 356 Argyle Square 433 Brougham Place 173, 208 Arthur Street 112n Brougham Street 198–9, 374 Ashley Terrace 389, 465, 468 Broughton 18, 36–8, 41–2, 54, 77 Atholl Terrace 212 Broughton Loan 55 Broughton School 112n Bainfield 173 Broughton Street 79 Balgreen 397 Brown Square 476 Balgreen Road 389 Brown Square School 112n Balmoral Place 377 Brunstane 230 Bangholm Bower 86 Brunswick Street 82, 109, 145 Bareford’s Park 51, 55 Brunton Gardens 108 Barnton Terrace, Craigleith 384–6 Brunton Place 82, 465 Bathfield 196, 337, 492 Brunton Terrace 108, 462 Bedford Street 356 Bruntsfield 48, 96, 109, 168–9, 173, 200 Belgrave Crescent 245, 250–3, 269, 338 Bryson Road 168, 215, 226–7 Belgrave Place 250, 269, 288, 290–1, 303, Buccleugh Place 94 322, 338 Buchanan Street 108 Bell Place 397 Buckingham Terrace 245, 252, 256, 287, -

Proposed Developments in West Craigs St. John's Road

Let’s Talk about “corstorphine” PROPOSED DEVELOPMENTS IN WEST CRAIGS ST. JOHN’S ROAD AIR POLLUTION HISTORY OF EDINBURGH CROQUET CLUB SUMMER 2019 COFFEE CLUB FOR BEREAVED MEN A magazine produced by St Ninian’s Church, Corstorphine LETS TALK ABOUT CORSTORPHINE 1ISSUE 43 Welcome to Corstorphine Churches Carrick Knowe Parish Church Corstorphine Community Church Parish Priest: Fr. Jeremy Milne Church of Scotland Saughton Road North Glebe Road St Ninian’s Church www.ckchurch.org.uk https://corstorphinefaith.org.uk Church of Scotland Main Sunday Service: 11am Sunday Service: 10.30am St John’s Road July-August: 10.30am Pastor: Duncan Whitty www.corstorphinestninians.org.uk Evening Services as intimated Main Sunday Service: 10.30am Minister: Rev. Fiona Mathieson St Andrew’s Church Evening Services as intimated Church of Scotland Minister: Rev. James Aitken Corstorphine Old Parish Church Clermiston View Church of Scotland Kirk Loan https://clermistonstandrew.wixsite.com/ourchurch St Thomas’ Church www.corstorphineoldparish.org.uk Main Sunday Service: 10.30am Glasgow Road Main Sunday Service: 10.30am Minister: Rev. Alistair Keil www.saintthomas.org.uk Minister: Rev. Moira McDonald Main Sunday Service: 10.30am St Anne’s Church Rector: Rev. David McCarthy Corstorphine Craigsbank Parish Church Church of Scotland St Kentigern’s Roman Catholic Church of Scotland (One Church 2 centres) Kaimes Road www.craigsbankchurch.org.uk www.stannescorstorphine.org.uk Parkgrove Avenue East Craigs Church Centre Main Sunday Service: 11am www.stkentigernsedinburgh.co.uk (Bughtlin Market) 1 July - 12 August 10.30am Sunday Morning Mass: 9.30am Worship at 9.30am Minister: Rev. James Griggs Holy Days of Obligation: Craigsbank Church As announced (19 Craigs Bank) St John the Baptist Weekday Mass: Worship at 11am Roman Catholic As announced Joint services as announced often at St Ninian’s Road Parish Priest: Fr. -

1. First Look in Central, North, East, South Or West Edinburgh, According to Where the Project Is

To find projects that may be of most interest to you: 1. First look in Central, North, East, South or West Edinburgh, according to where the project is. 2. Then look for street names. CENTRAL EDINBURGH Cockburn Street Pedestrian area with limited access for deliveries etc Forest Road Protected cycle lanes George IV Bridge Protected cycle lanes Princes Street East End Buses/taxis/cycles only on Princes Street from North Bridge to South St David St Raeburn Place - Stockbridge Extra pedestrian space The Mound Protected cycle lanes Tollcross Extra pedestrian space Victoria Street Pedestrian area with limited access for deliveries etc Waverley Bridge Pedestrian area with limited access for deliveries etc NORTH EDINBURGH Arboretum Place Relocation of parking at West Gate to provide safer pedestrian and cycle access and crossing to Inverleith Park Crewe Road South Protected cycle lanes Ferry Road Protected cycle lanes Links Gardens Road closure in middle of Leith Links Muirhouse Parkway Pennywell Road Protected cycle lanes Silverknowes Parkway Protected cycle lanes EAST EDINBURGH Duddingston Road Protected cycle lanes Hope Lane Road closure reducing traffic on very narrow road that forms a walking/cycling connection to Portobello Kings Place Road closure and parking removal linking Portobello and Seafield promenades Milton Road West Extra bus Lanes and protected cycle lanes Portobello High Street Extra pedestrian space Seafield Street Protected cycle lanes joining off-road cycle paths Stanley Street Road closure reducing traffic on very narrow road that forms a walking/cycling connection to Portobello Willowbrae Road Extra bus Lanes and protected cycle lanes SOUTH EDINBURGH Braid Avenue Meadows to Greenbank quiet route.