American Bandstand

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Randy Nataraj-Allen Piano and Voice

Randy Nataraj-Allen Piano and Voice Formal Education: Master’s Degree: curriculum & Instructional / Technology - Grand Canyon University – Phoenix, AZ Bachelor of Church Music: Samford University – Birmingham, AL Major: Voice, Minor: Piano Awards / Accolades: Voted “Educator of the Year 2002-2003” Experience / Performances: August 1995 – Present: Music Teacher, Pinellas County Schools – Largo, FL 2007 Elementary All county chorus conductor 2002-2003 Elementary Music Educator of the Year James B. Sanderlin PK-8 IB World School: grades K-5 and two classes Fairmount Park Elementary: K-5 Music Itinerate Northwest Elementary K-5 Music Itinerate Lakewood Elementary K-5 Music Itinerate Starkey Elementary: K-5 Music Itinerate Cypress Woods Elementary: K-5 two choruses and recorder South Ward Elementary: K-5 and two choruses Orange Grove Elementary: k-3, SLI and SLD (195-1996 only) January 1991-Present: Voice and Piano Instructor: Marcia P Hoffman School of the Arts William Cusick Piano, Vocal Instruction, Accompanist, Music Director for Stage productions Formal Education: Bachelor Degree in Music Education from State University of New York and Fredonia One semester abroad in Antwerp, Belgium studying music and art at the Royal Flemish Conservatory of Music Master Degree in Piano Performance from University of South Florida Awards / Accolades: Voted Favorite Musical Director six times by the Grapevine Theater Publication. Statement of philosophy: Even your smallest experiences can open doorways to greater learning. Experience / Performances: As a Music Director he has worked at Bartk’e Dinner Theatre in Tampa, the Show Boat Dinner Theatre in Clearwater, Hudson, community Theaters throughout Pinellas County, various high schools and instructs and accompanies for the Marcia P. -

Adult Contemporary Radio at the End of the Twentieth Century

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Music Music 2019 Gender, Politics, Market Segmentation, and Taste: Adult Contemporary Radio at the End of the Twentieth Century Saesha Senger University of Kentucky, [email protected] Digital Object Identifier: https://doi.org/10.13023/etd.2020.011 Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Senger, Saesha, "Gender, Politics, Market Segmentation, and Taste: Adult Contemporary Radio at the End of the Twentieth Century" (2019). Theses and Dissertations--Music. 150. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/music_etds/150 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Music at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Music by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. -

School Cluster List

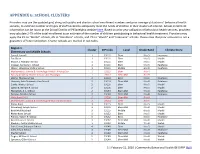

APPENDIX G: SCHOOL CLUSTERS Providers may use the updated grid, along with public and charter school enrollment numbers and prior average utilization of behavioral health services, to estimate number and types of staff needed to adequately meet the needs of children in their clusters of interest. School enrollment information can be found at the School District of Philadelphia website here. Based on prior year utilization of behavioral health services, providers may calculate 2-7% of the total enrollment as an estimate of the number of children participating in behavioral health treatment. Providers may apply the 2% to “Model” schools, 4% to “Reinforce” schools, and 7% to “Watch” and “Intervene” schools. Please note that prior utilization is not a guarantee of future utilization. Charter schools are marked in red italics. Region 1 Cluster ZIP Code Level Grade Band Climate Score Elementary and Middle Schools Carnell, Laura H. 1 19111 Elem K to 5 Intervene Fox Chase 1 19111 Elem K to 5 Model Moore, J. Hampton School 1 19111 Elem K to 5 Model Crossan, Kennedy C. School 1 19111 Elem K to 5 Reinforce Wilson, Woodrow Middle School 1 19111 Middle 6 to 8 Reinforce Mathematics, Science & Technology II-MaST II Rising Sun 1 19111 Elem K to 4 Tacony Academy Charter School - Am. Paradigm 1 19111 Elem-Mid K to 8 Holme, Thomas School 2 19114 Elem K to 6 Reinforce Hancock, John Demonstration School 2 19114 Elem-Mid K to 8 Reinforce Comly, Watson School 2 19116 Elem K to 5 Model Loesche, William H. School 2 19116 Elem K to 5 Model Fitzpatrick, A. -

JFK Characters

Page 1 JFK Characters As you start reading about the JFK John Abt assassination, you quickly realize that there are thousands of people involved John Abt was a lawyer for the Communist party. in one way or another. Keeping track of When LHO was arrested in Dallas, he asked for Abt who’s who gets to be a challenge. to represent him. LHO wasn’t a communist or That’s why I created this list of some of marxist, but he pretended to be as part of his CIA the major (and minor) players in the undercover assignment. Asking to have Abt as his complex story. It is designed to give lawyer was intended to be a signal to his you a quick idea of the most relevant intelligence handlers that his cover was still intact facts about each of the characters and that he was still playing along. He wanted his listed, and it is intended as a quick handlers to know that they could count on his reference tool. (However, just reading silence. down the list of characters is one way to get a lot of information about the events of November 22, 1963, in Juan Adames Dallas, Texas.) Juan Adames provided information to HSCA It is by no means complete, as that is (House Select Committee on Investigations) beyond my scope. But I do plan to keep investigator Gaeton Fonzi, working in Miami. adding characters as I learn more Adames told Fonzi about Bernardo Gonzales de about the death of JFK. Torres Alvarez (de Torres), who had been working for CIA since 1962. -

Pennsylvania

Philadelphia Pennsylvania Contact: SOPA: Kristin Craven, Special Events and Marketing Manager 610-630-9450 x252 | [email protected] FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: School District of Philadelphia Hosts Special Olympics Philadelphia’s Unified Youth Summit Seven Philadelphia schools will come together to share ideas on how to bring inclusion and respect to schools. (PHILADELPHIA, PA October 5, 2015) – Special Olympics Philadelphia will partner with the School District of Philadelphia to bring the fall Unified Youth Summit to the Education Center at 440 N Broad Street. The Unified Youth Summit will run from 9:00am to 1:00pm. More than 100 students and teachers are expected to attend. Schools that are represented include: Abraham Lincoln High School, Universal Charter Audenried High School, Frankford High School, Furness High School, High School of the Future, Martin Luther King High School, and Thomas Edison High School. Also in attendance will be, Bettyann Creighton, Director of Health, Safety and Physical Education as well as Jack Perry, Deputy Chief of Academic Enrichment. This year’s theme of the Unified Youth Summit is I Have a Voice. The Summit will kick off with SOPA Athlete Jordan Schubert sharing his journey through Special Olympics and how the high school atmosphere has changed from when he was in high school. During the Unified Youth Summit, students’ voices will be heard as they discuss how to create and sustain a Unified Youth Committee (UYC) within their schools and activities they can plan to promote inclusion and respect. This is a student group comprised of students with and without intellectual disabilities working together to plan events and opportunities within the school for inclusion and respect. -

The Women's Center of Montgomery County Spring Champagne Brunch

THE WOMEN’S CENTER OF MONTGOMERY COUNTY SPRING CHAMPAGNE BRUNCH Benefi tting the Women’s Center of Montgomery County Domestic Violence Program, serving more that 4000 victims each year Sunday, April 6, 2014 SERVING WESTERN NEW YORK SINCE 1893 Risk Management "Your Personal 401k/403b Manager" SAPERSTON ASSET MANAGEMENT A Full Service Brokerage. Member: FINRA, SIPC, MSRB. Investment Counseling & Wealth Management 716-854-7541 941-359-2604 © In the search for property, it’s SAPERSTON REAL ESTATE Serving The Industrial & Commercial Real Estate Markets. 716-847-1100 © In the pursuit of better business, it’s SAPERSTON MANAGEMENT For Tax Assistance, Payroll Services, Bookkeeping & Financial Reporting. Life Insurance and Structured Settlements 716-854-7541 “THE DOLLAR DOCTOR” Listen to the NEW DOLLAR DOCTOR RADIO SHOW with a call-in format each Saturday 10 am to 11 am on ESPN 1520 AM (Bflo) & SUNNY 1450/1320 AM (Sarasota) archived at www.saperston.com TM TM 1-800-879-7541 172 LWa[ijh[[j©^WcXkRG, NY 14075 GOLL^_bbl_[mijh[[j©SARASOTA, FL 34239 The Board of Directors and the Special Events Committee of the Women's Center of Montgomery County welcome you to our Champagne Brunch Honoring Jerry Blavat with Distinguished Panelists Debbi Calton Michaela Majoun Denny Somach Featuring Guest Speaker: Dr. Doreen Loury With special thanks to our Moderator & Friend: Larry Kane Board of Directors: Lawrence Pauker and Sandra Capps, Co-Presidents Andra Seidner, Vice-President Sandra Hyman, Treasurer Sharlene Kalender, Secretary Roanna Burnell Carol Chwal Bruce -

Andy Higgins, BA

Andy Higgins, B.A. (Hons), M.A. (Hons) Music, Politics and Liquid Modernity How Rock-Stars became politicians and why Politicians became Rock-Stars Thesis submitted for the degree of Ph.D. in Politics and International Relations The Department of Politics, Philosophy and Religion University of Lancaster September 2010 Declaration I certify that this thesis is my own work and has not been submitted in substantially the same form for the award of a higher degree elsewhere 1 ProQuest Number: 11003507 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 11003507 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 Abstract As popular music eclipsed Hollywood as the most powerful mode of seduction of Western youth, rock-stars erupted through the counter-culture as potent political figures. Following its sensational arrival, the politics of popular musical culture has however moved from the shared experience of protest movements and picket lines and to an individualised and celebrified consumerist experience. As a consequence what emerged, as a controversial and subversive phenomenon, has been de-fanged and transformed into a mechanism of establishment support. -

The Philadelphia Sound This Is the Fourth Article in a Series Highlighting ASA’S 50S, and 60S

VOLUME 33 JULY/AUGUST 2005 NUMBER 6 2005 ASA Annual Meeting . Our 100th Meeting! The Philadelphia Sound This is the fourth article in a series highlighting ASA’s 50s, and 60s. The city was home to more African-American sound than they had upcoming 2005 centennial meeting in Philadelphia. jazz musicians than perhaps any city, previously heard in the California- save New York. Musicians found each centric “cool” jazz movement, East by Jerome Hodos, Franklin and Marshall protected, fertile enclave in which other gigs and played together—John Coast jazz musicians in the mid-1950s College, and David Grazian, cultural production can germinate. Coltrane, for example, played in both created a roots-oriented jazz—called University of Pennsylvania Musical innovation has relied on the Jimmy Heath’s and Jimmy Smith’s hard bop—that incorporated significant vitality of largely segregated community bands, and later hired local talents elements from blues and black church Since World War II, music has been institutions such as the black church. For Jimmy Garrison and McCoy Tyner for music. Philadelphia was a main center Philadelphia’s public face to the world. instance, rhythm-and-blues pioneer his own classic quartet. In search of a for hard bop, home to crucial performers While fulfilling their duties as unofficial Solomon Burke long led his own more urban, gritty, and what was like Clifford Brown, Benny Golson, John representatives of the “City of Brotherly congregation in the city. (Another thought of as a more authentically See Philadelphia, page 7 Love”, local musicians worked to codify example: the white, teen pop of the late and symbolize the state of the city’s 1950s was made popular via Dick black community through a succession Clark’s TV show American Bandstand, of distinct musical styles. -

PDF EPUB} You Only Rock Once My Life in Music by Jerry Blavat You Only Rock Once : My Life in Music

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} You Only Rock Once My Life in Music by Jerry Blavat You Only Rock Once : My Life in Music. Jerry Blavat's rockin' life story pulses with celebrity names, infamous episodes and "offers readers an insider's view into the golden era of rock and roll and pop music and entertainment" raves Publishers Weekly . The long-awaited autobiography of entertainment icon Jerry Blavat, You Only Rock Once is the wildly entertaining and unfiltered story of the man whose career began at the age of 13 on the TV dance show Bandstand and became a music legend. Lifelong friendships with the likes of Sammy Davis Jr. and Frank Sinatra, a controversial relationship with Philadelphia Mafia boss Angelo Bruno that resulted in a decade-long FBI investigation, and much more colors this amazing journey from the early 60s through today. Now, some 50 years after his first radio gig, Blavat puts it all in perspective in this uniquely American tale of a "little cockroach kid" borne out of the immigrant experience who lived the American Dream. Отзывы - Написать отзыв. You Only Rock Once. Although people always remember the music of their youth, they often forget who introduced them to it. For those who grew up in the Philadelphia area, chances are they heard the hits of the 1960sâ . Читать весь отзыв. YOU ONLY ROCK ONCE: My Life in Music. A longtime disk jockey spins a stack of memories about rock, the mob and surviving the music business. Blavat spent the '60s crafting a fast- talking, larger-than-life radio persona that attracted . -

Constructing and Performing an On-Air Radio Identity in a Changing Media Landscape

CONSTRUCTING AND PERFORMING AN ON-AIR RADIO IDENTITY IN A CHANGING MEDIA LANDSCAPE A Dissertation Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY by David F. Crider January 2014 Examining Committee Members: Dr. Nancy Morris, Advisory Chair, Department of Media Studies and Production Dr. Patrick Murphy, Department of Media Studies and Production Dr. Donnalyn Pompper, Department of Strategic Communication Dr. Catherine Hastings, External Member, Susquehanna University ii © Copyright 2014 by David F. Crider All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT The radio industry is fighting to stay relevant in an age of expanding media options. Scholarship has slackened, and media experts say that radio’s best days are in the past. This dissertation investigates how today’s radio announcer presents him/herself on the air as a personality, creating and performing a self that is meant for mass consumption by a listening audience. A participant observation of eleven different broadcast sites was conducted, backed by interviews with most key on-air personnel at each site. A grounded theory approach was used for data analysis. The resulting theoretical model focuses on the performance itself as the focal point that determines a successful (positive) interaction for personality and listener. Associated processes include narrative formation of the on- air personality, communication that takes place outside of the performance, effects of setting and situation, the role of the listening audience, and the reduction of social distance between personality and listener. The model demonstrates that a personality performed with the intent of being realistic and relatable will be more likely to cement a connection with the listener that leads to repeated listening and ultimately loyalty and fidelity to that personality. -

ELECTORAL VOTES for PRESIDENT and VICE PRESIDENT Ø902¿ 69 77 50 69 34 132 132 Total Total 21 10 21 10 21 Va

¿901¿ ELECTORAL VOTES FOR PRESIDENT AND VICE PRESIDENT ELECTORAL VOTES FOR PRESIDENT AND VICE PRESIDENT 901 ELECTION FOR THE FIRST TERM, 1789±1793 GEORGE WASHINGTON, President; JOHN ADAMS, Vice President Name of candidate Conn. Del. Ga. Md. Mass. N.H. N.J. Pa. S.C. Va. Total George Washington, Esq ................................................................................................... 7 3 5 6 10 5 6 10 7 10 69 John Adams, Esq ............................................................................................................... 5 ............ ............ ............ 10 5 1 8 ............ 5 34 Samuel Huntington, Esq ................................................................................................... 2 ............ ............ ............ ............ ............ ............ ............ ............ ............ 2 1027 John Jay, Esq ..................................................................................................................... ............ 3 ............ ............ ............ ............ 5 ............ ............ 1 9 John Hancock, Esq ............................................................................................................ ............ ............ ............ ............ ............ ............ ............ 2 1 1 4 Robert H. Harrison, Esq ................................................................................................... ............ ............ ............ 6 ............ ............ ............ ............ ............ ........... -

The Warren Report and the Jfk Assassination: Five Decades of Significant Disclosures

THE WARREN REPORT AND THE JFK ASSASSINATION: FIVE DECADES OF SIGNIFICANT DISCLOSURES September 25-28, 2014 Bethesda Hyatt Regency Become a Member of the AARC Support the declassification of government records relating to political assassinations by becoming a member of the AARC. Visit our website to join online or print application to send with check or money order. Annual Membership: Contribution of $35 or more Annual Student Membership: Contribution of $10 or more Lifetime membership: Contribution of $500 or more Member benefits include: • Discounts on AARC CD-ROM • e-mail updates and newsletters • Discounted use of on-site AARC Research facilities • Discounts on book purchases from the AARC • Discounts on AARC-sponsored events Program Schedule Thursday September 25, 2014 6:30 PM until conclusion: Meet and greet in our Hospitality Suite (the Presidential Suite). Free to AARC members. Membership can be purchased at the door for $35 less the $25 registration fee discount for members or $10. 7:00-9:00 PM Registration Friday, September 26, 2014 PRELIMINARIES 8:00-8:10 AM Introduction: Alan Dale and James Lesar 8:15-8:25 AM Alan Dale: Kickoff and Introduction of AARC President James Lesar: “Why This Conference Matters” 8:30-8:40 AM AARC Executive Director Jerry Policoff: Historical Background and Conference Preview 8:45-8:55 AM Andrew Kreig: “Current Implications of JFK Assassination Cover-Up” 9:00-9:20 AM Alan Dale: “What We Now Know that the Warren Commission Didn’t Know” 9:20-9:30 AM Break THE CULTURE OF SECRECY AND DEMOCRATIC ACCOUNTABILITY 9:30-11:00 AM Prof.